A big Nazi eagle with a swastika under its talons is such a divisive symbol that it has been kept hidden inside a sealed crate in a Uruguayan navy warehouse for more than a decade.

FILE- In this Feb. 10, 2006 file photo, workers salvage the eagle from the World War II German pocket battleship Admiral Graf Spee, in Montevideo, Uruguay. (AP Photo/Marcelo Hernandez, File)

The 800-pound bronze piece was part of the stern of the German battleship Admiral Graf Spee that sank off the South American country's coast at the outset of World War II. Controversy has swirled around the eagle ever since it was recovered in 2006, and now a battle has broken out over its fate after the government asked lawmakers and Uruguay's Jewish community what it should do with it.

Suggestions have ranged from exhibiting or auctioning the Third Reich symbol to keeping it hidden or even destroying it. The debate rages as far-right demonstrations, including the one in Charlottesville, Virginia, have created fears of a rise in neo-Nazism.

"Our concern is that the eagle doesn't generate a Nazi sanctuary in Uruguay that will draw Nazis from all over the region," said Israel Buszkaniec, president of the country's Jewish Central Committee.

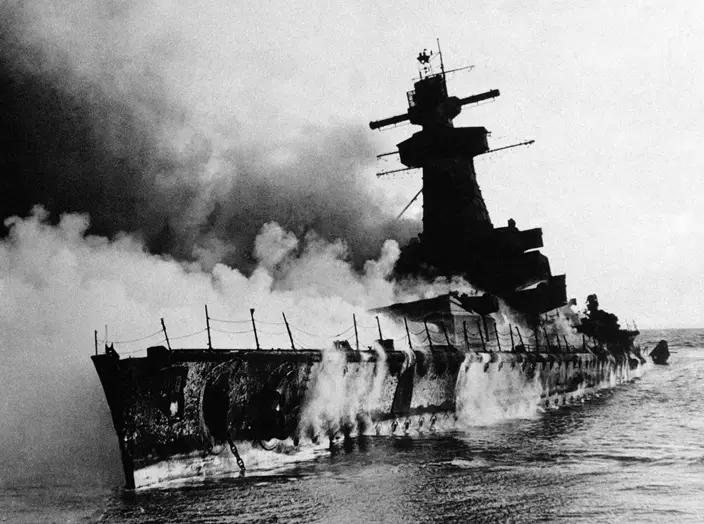

FILE - In this Dec. 19, 1939 file photo, German battleship Admiral Graf Spee burns as she is scuttled by her crew, ordered by its captain to prevent it and its then state-of-the-art technology from falling into enemy hands, near Montevideo, Uruguay, where injured and dead sailors were taken ashore during the "Battle of the River Plate." (AP Photo, File)

The Graf Spee was a symbol of German naval might early in the war. It prowled the South Atlantic and sank several Allied merchant ships before warships from Britain and New Zealand tracked it down and damaged it during the "Battle of the River Plate" that began on Dec. 13, 1939.

The damaged Graf Spee limped into the harbor of Uruguay's capital, Montevideo, where injured and dead sailors were taken ashore. Its captain ordered the ship scuttled, sinking it a few miles from Montevideo to prevent it and its then state-of-the-art technology from falling into Allied hands. Most of the crew was taken by ship to Buenos Aires in neighboring Argentina and the captain killed himself days later.

In this Aug. 17, 2017 photo, a woman takes a photo of a canon that was part of the German battleship Admiral Graf Spee on display at the Naval Museum in Montevideo, Uruguay. (AP Photo/Matilde Campodonico)

In 2004, private investors from the United States and Europe funded a multimillion-dollar effort to remove the ship piece by piece from the bottom of the River Plate. In February 2006, a salvage team brought up the eagle.

Thousands of curious people gathered at a hotel in Montevideo where it was exhibited. But the exhibition lasted only a couple of months because of controversy surrounding the symbol.

Germany said it was the rightful owner of the eagle and the vessel. Jewish groups asked that the swastika under the eagle's talons be covered with a cloth. Insurance companies demanded a fortune to exhibit the piece. Finally, the eagle was put in the navy warehouse.

The salvage team sued to demand the right to sell it. But Uruguay's Supreme Court ruled in 2014 that the eagle belonged to the state. The ruling said, however, that if the piece is sold, the salvage group would have the right to 50 percent of the proceeds.

This Aug. 17, 2017 photo shows the burial spot of 36 fallen officers from the German battleship Admiral Graf Spee, who died in the "Battle of the River Plate" that began on Dec. 13, 1939, at the North Cemetery in Montevideo, Uruguay. (AP Photo/Matilde Campodonico)

Foreign Minister Rodolfo Nin Novoa recently discarded Germany's claim to the eagle, saying, "What is left is not the ship, but its remains."

Determined to finally decide the fate of the bronze eagle, Defense Minister Jorge Menendez discussed options earlier this month with members of Uruguay's Jewish Central Committee and later with leaders of the country's four main political parties.

Gonzalo Reboledo, who represented the governing Broad Front coalition at the meeting, said the government is evaluating the idea of exhibiting the eagle at a museum dedicated to "The Battle of the River Plate."

Other items that have been extracted from the Graf Spee include uniforms with swastikas, the ship's anchor and a cannon. A room at Uruguay's Naval Museum displays a stretcher that was used to carry injured German sailors, binoculars and a medallion carved with Adolf Hitler's name and a swastika.

In this Aug. 17, 2017 photo, a plaque in German and Spanish hangs at the entrance of the area in commemoration of 36 officers from the German battleship Admiral Graf Spee. The crew was taken by ship to Buenos Aires in neighboring Argentina and the captain committed suicide days later. (AP Photo/Matilde Campodonico)

But nothing inflames debate as much as the eagle.

"I wouldn't leave it here. It hasn't been too long since WWII, the Holocaust and 50 million people who died because of the madness of the Nazis," said former lawmaker Julio Aguiar, who opposes exhibiting the eagle. "You look at the United States and it seems crazy that Nazi groups still exist, but they do. And they exist here as well."

Reboledo of the Broad Front said other parties are more inclined to sell it. Opposition lawmaker Jorge Gandini at first proposed that the funds raised go to Uruguay's military but now believes it would be better to exhibit the eagle.

In this Aug. 17, 2017 photo, the anchor of the German battleship Admiral Graf Spee, which was sunk by its crew in 1939, is displayed at the port of Montevideo, Uruguay. (AP Photo/Matilde Campodonico)

Manuel Esmoris, an expert on national heritage, said the eagle should be melted or donated to London's Imperial War Museum.

"It's a dangerous object and there are no controlled sales of pieces like this," he said. "It can be bought by front men who can then sell it to neo-Nazis. There is no other market in the world for this eagle than one linked to neo-Nazis."

Others feel the "Battle of the River Plate" is a part of Uruguay's history and remains engrained in its collective memory. The tombs of German and English sailors who died in the battle are kept in Montevideo, and several members of the Graf Spee's crew lived in Uruguay. Carlos Grossmuller, a popular soccer player, is the grandson of the ship's cook.

Former President Julio Maria Sanguinetti recently suggested the eagle go on display in Uruguay because of its historical importance.

"To imagine that, as some say, it could lead to a certain Nazi cult is really absurd because it is actually the contrary: It's a monument to their defeat," he wrote in a newspaper article.