Is it a symbol of the eternal return?

A man was filming a snake and said, “The stupid snake is actually eating itself.” Despite his clear confusion, the man joked, “It’s like a snake neckless. Actually, it’s a sneck-less. If he stays clamped on like that, I’m going to wear him as a sneck-less.”

Click to Gallery

A copy of a 1478 drawing by Theodoros Pelecanos, of an alchemical tract attributed to Synesius. (Photo via Wikipedia)

He then picks up the snake and wraps it around his neck as if it is a piece of jewellery, shouting to his lady-friend in another room “He’s stayed clamped on, I’ve got a neckless.”

This clip was filmed in the UK on October 18, 2017. Some neitizens said it just like the Ouroboros, an ancient symbol depicting a snake or dragon eating its own tail.

Originating in Ancient Egyptian iconography, the Ouroboros entered western tradition via Greek magical tradition and was adopted as a symbol in Gnosticism and Hermeticism, and most notably in alchemy. Via medieval alchemical tradition, the symbol entered Renaissance magic and modern symbolism, often taken to symbolize introspection, the eternal return or cyclicality, especially in the sense of something constantly re-creating itself. It also represents the infinite cycle of nature's endless creation and destruction, life and death.

A copy of a 1478 drawing by Theodoros Pelecanos, of an alchemical tract attributed to Synesius. (Photo via Wikipedia)

Neitizen Akrudibum Rum explaind this phenomenon from a scientific point of view. He wrote, “When snakes become too hot, they will get confused and disoriented. Their ramped-up metabolism will also lead to a false sense of hunger, thus desiring to eat the thing at their first glance.

Generally speaking, captive snakes live alone and there is no enough food offered to them in such situation. As a result, they have to attack themselves by eating their tail. In addition, it will happen when they are shedding and have diminished eyesight, because they mistake their tail for prey.

In the case of their self-cannibalizing, if you can reduce the temperature by turning off heat lamps and spritzing the snake with cool water, it can be much helpful in cutting down the stress of the snake that might let go; sometimes the veterinarian’s intervention is necessary in this respect.

These fatal episodes can take place constantly, because snakes have evolved to trap food and guide it in. When they begin with eating something, it will be very hard for them to let it go.

So next time when you see such scene, you will be fully aware of what is happening. If you want to keep your pet snake in a good condition, feed them with enough food and maintain the proper room temperature for them so as to avoid the fatal episode.”

MEXICO CITY (AP) — The almighty eagle perched on a cactus while devouring a serpent on Mexico’s flag hints at the myth behind the foundation of the country’s capital.

It's a divine sign in an ancient legend, according to which the god Huitzilopochtli asked a group called the Mexica to leave their homeland in search of a place to establish a new city.

It took some 175 years before they spotted the sacred omen and established the city of Tenochtitlan in 1325 where Mexico City stands today.

How the eagle, the cactus and the serpent became an emblem and endured through the European conquest is the focus of a new exhibition. “A coat of arms, an emblem, a symbol of identity,” runs through Dec. 15 at the Old City Hall in downtown Mexico City.

The exhibit is among the government’s activities marking the 700th anniversary of the founding of the Mexica capital.

“Recognizing Tenochtitlan doesn’t mean recalling a dead past, but rather the living heartbeat that still beats beneath our city,” President Claudia Sheinbaum said during an official ceremony in July. “It was the center of an Indigenous world that built its own model of civilization — one in harmony with the Earth, the stars, and its gods and goddesses.”

Fragments of that civilization lie underneath the Old City Hall, the current seat of Mexico City’s government.

Built by order of Spanish conqueror Hernán Cortés in 1522, its construction used stones from ancient Mexica sacred sites. The building has been renewed over time, but its halls have witnessed centuries of governance and symbolism.

“Holding the exhibition in this City Hall, a place of decisions and memory, is a way to recognize the history of those who once inhabited it and how its transformations still echo in Mexico City’s identity,” said Mariana Gómez Godoy, Director of Mexico City’s Cultural Heritage, during the exhibit’s inauguration in November.

The Mexica themselves recounted their story after Tenochtitlan fell to the Europeans. Several codices — including some produced after the conquest — depict the path that led them to fulfill their deity’s task.

According to the Templo Mayor Museum, the region’s pre-Hispanic people preserved the origin story of a long journey that led to the founding of Tenochtitlan as a cornerstone of their traditions.

They identified a small island in Lake Texcoco —now central Mexico City— as the place where the Mexica saw the eagle foretold by Huitzilopochtli.

Some scholars, however, revisit the narrative with a different lens. Eduardo Matos Moctezuma — an acclaimed archaeologist from Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History — has argued that the legend is a symbolic retelling of historical events, rather than a literal claim about divine prophecy.

The new exhibit offers a historical overview of how the image evolved — from its establishment as the city’s coat of arms in 1523 under Emperor Charles V to its transformation into an emblem of Mexico as an independent nation.

Curated by researcher Guadalupe Lozada, it also displays images portraying how it was adopted by the religious orders in charge of converting the Indigenous people to Catholicism.

While the eagle and cactus were already adopted by Europeans in the mid-16th century, the Jesuits introduced the serpent decades later. “From then on, it would remain a symbol of the city’s identity — one that would also spread throughout the rest of New Spain,” Lozada said.

According to her, plenty of monasteries dating back to the 17th century attest to how friars displayed the eagle and cactus in their sanctuaries. Even today, the emblem can still be seen above the façade of Mexico City’s cathedral and inside one of its chapels.

“Such was the strength of Mexica culture that the evangelizers sought to adopt it rather than exclude it,” she said. “It was like saying, ‘I acknowledge your history.’”

The same logic applied with the European conquerors. Even as they ordered the destruction of the Mexica religious complexes, the representation of the foundational myth was not erased from history.

“For them, conquering a city like Tenochtitlan was a matter of pride and therefore they never intended to deny its existence,” Lozada said. “This meant that the strength of the city buried beneath the new one underlies it and resurfaces — as if it had never disappeared.”

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

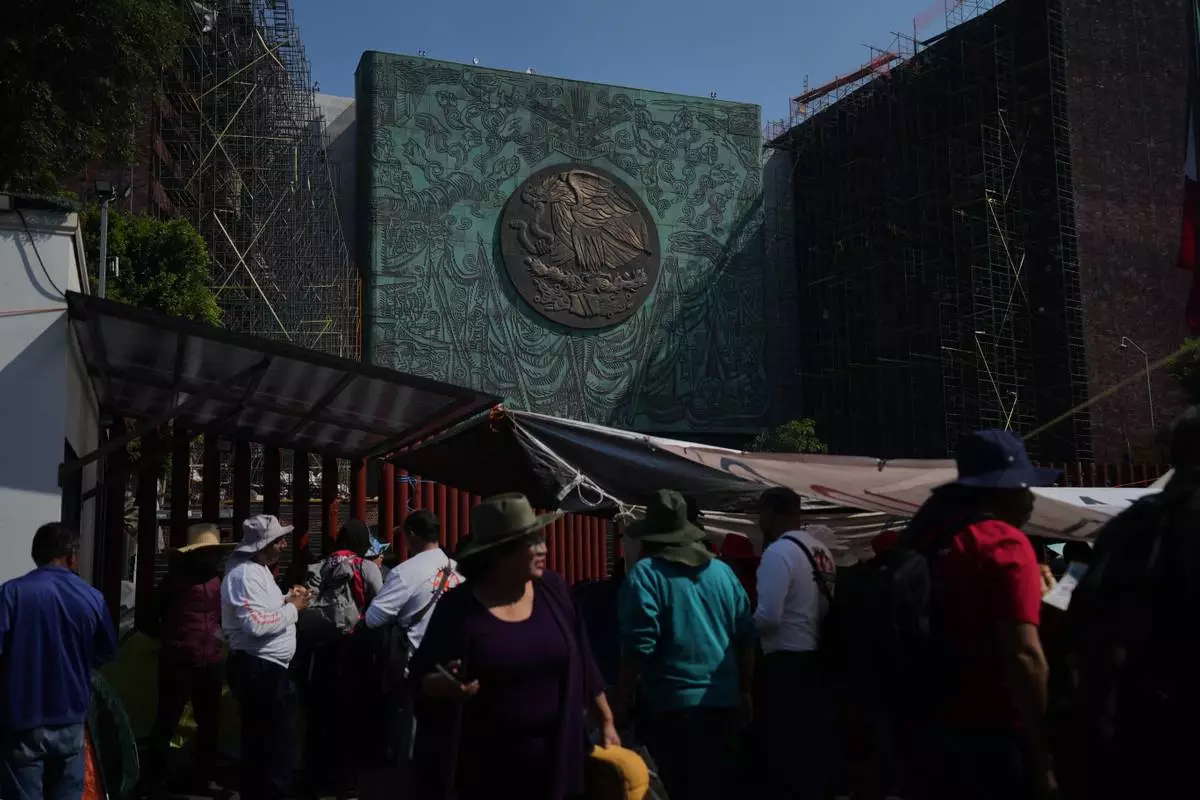

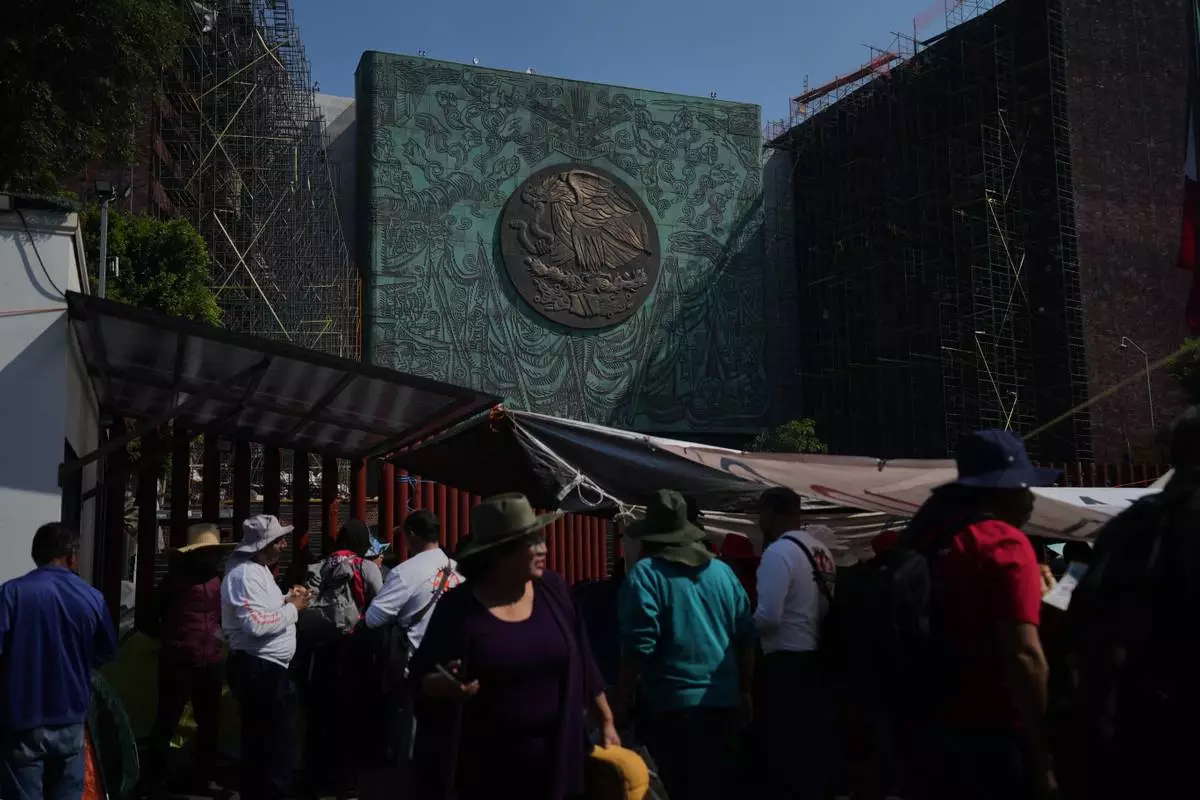

Protesters gather in front of the Legislative Palace of San Lazaro in Mexico City, where the Mexican coat of arms is visible on the building's façade, Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Claudia Rosel)

People sit on benches in Plaza del Aguilita, where the evolution of the Mexican coat of arms is showcased, Mexico City, Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Claudia Rosel)

The entrance of Mexico City's National Museum of Anthropology features Mexico's national emblem on its façade, Friday, Nov. 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Claudia Rosel)

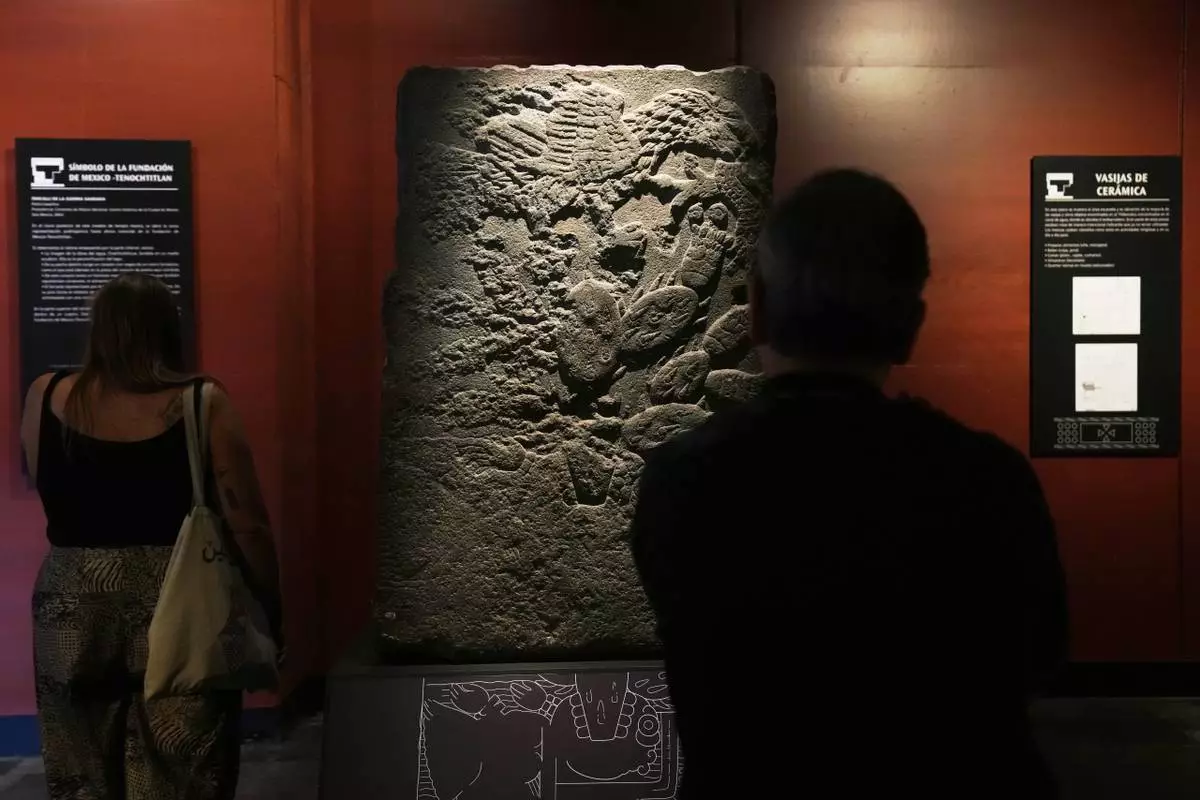

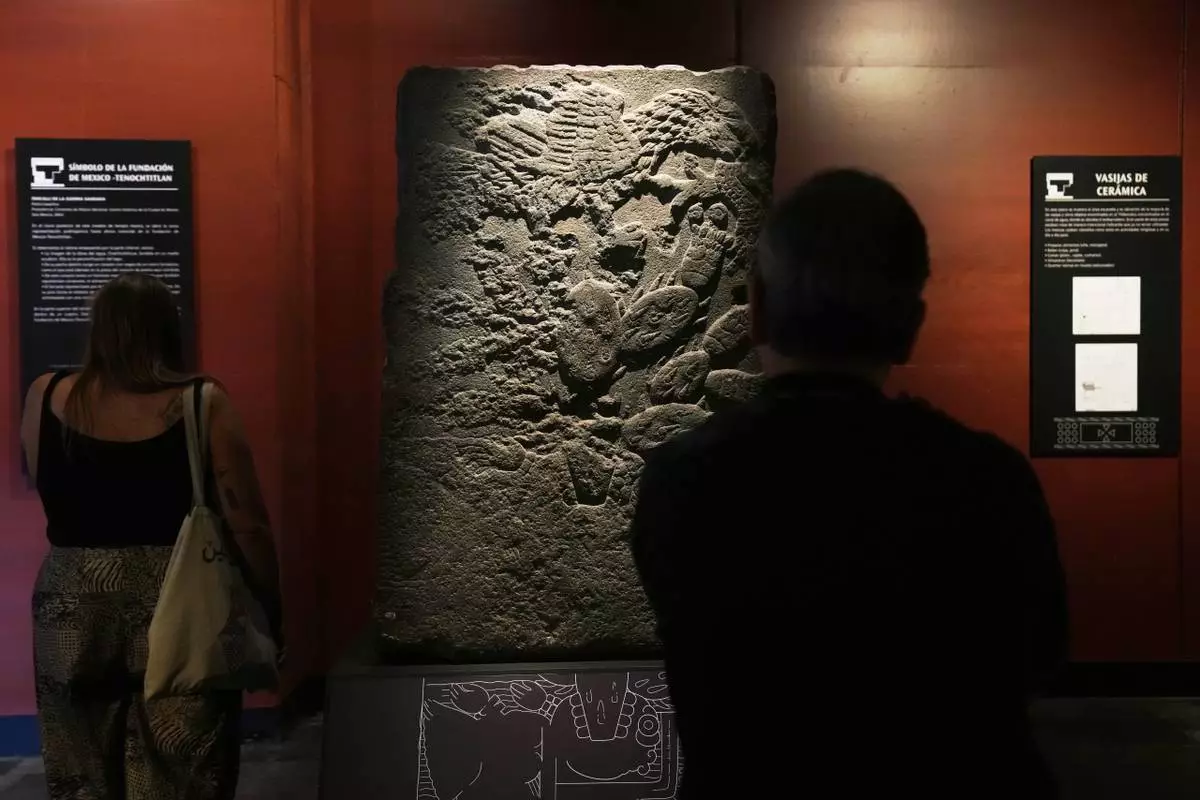

The Teocalli of the Sacred War, the only archaeological piece bearing the carved symbol of Tenochtitlan's founding, an eagle perched on a cactus, is on display at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, Friday, Nov. 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Claudia Rosel)

People at the square of Aguilita in Mexico City walk past a central sculpture depicting Mexico's coat of arms which shows an eagle perched on a cactus devouring a rattlesnake, Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Claudia Rosel)

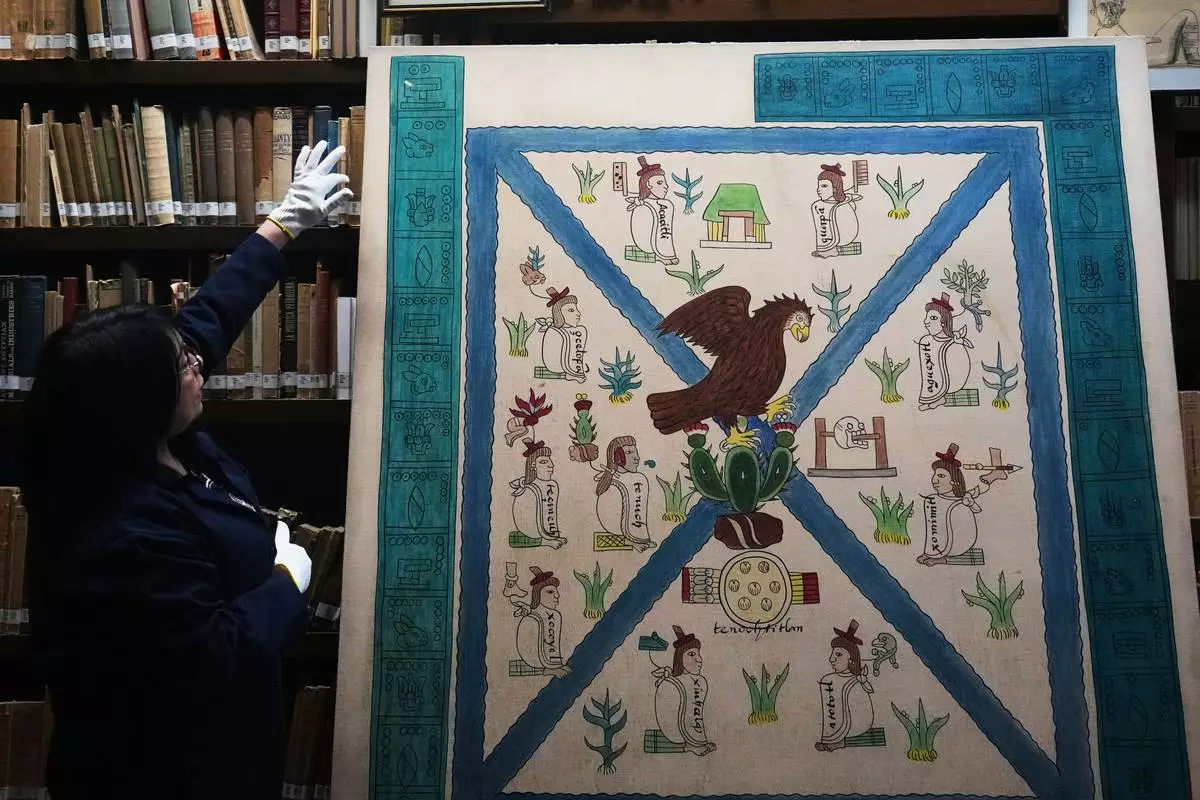

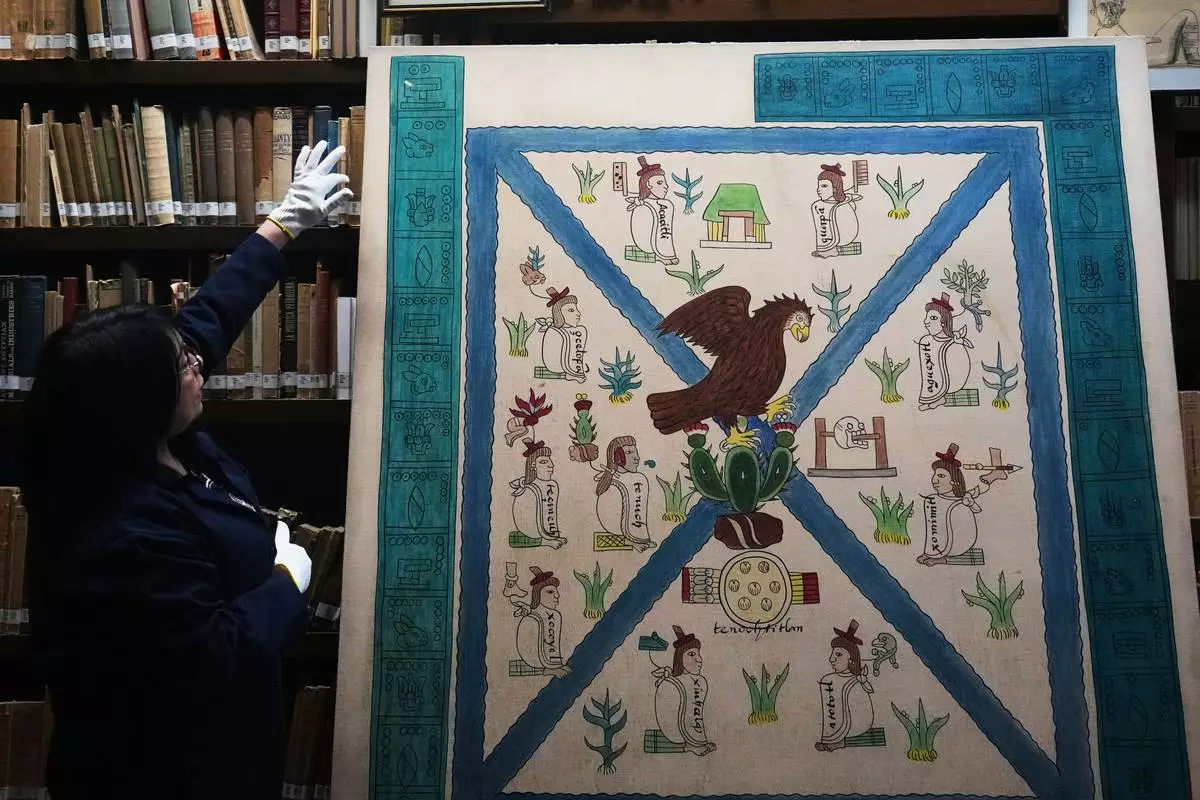

Rosalba Sanchez Flores, a historian at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, points to the details of Mexico's coat of arms as depicted in the Codex Mendoza, Friday, Nov. 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Claudia Rosel)

People sit on benches in Plaza del Aguilita, where the evolution of the Mexican coat of arms is showcased, Mexico City, Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Claudia Rosel)

People sit at a rooftop bar overlooking Mexico City's Fine Arts Palace, where the Mexican coat of arms is visible atop the building's dome, Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Claudia Rosel)

Mexico's coat of arms decorates a large flag in the city's Zocalo square, Mexico City, Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Claudia Rosel)