Adolf Hitler went in wartime for revenge. Angela Merkel plans a pilgrimage in the name of peace. Two German chancellors, with opposite aims and the same destination: a train car in a French forest.

Hitler literally tried to rewrite history in 1940 when the Nazi leader commanded the dining coach to serve France the humiliation Germany suffered in that same spot on the last day of World War I.

Click to Gallery

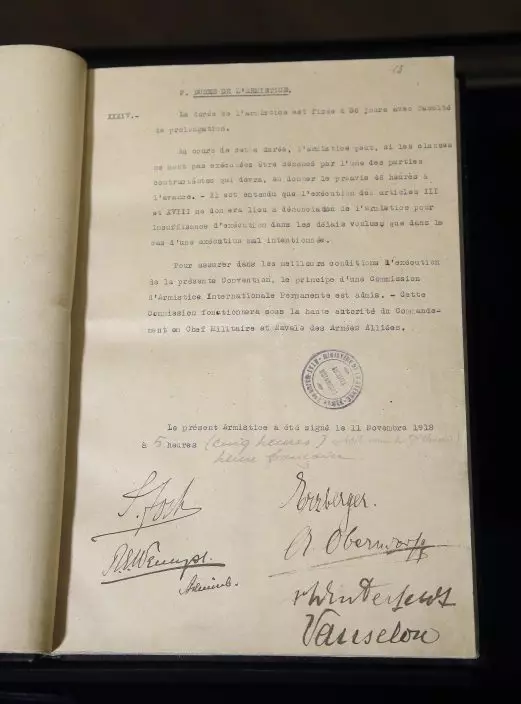

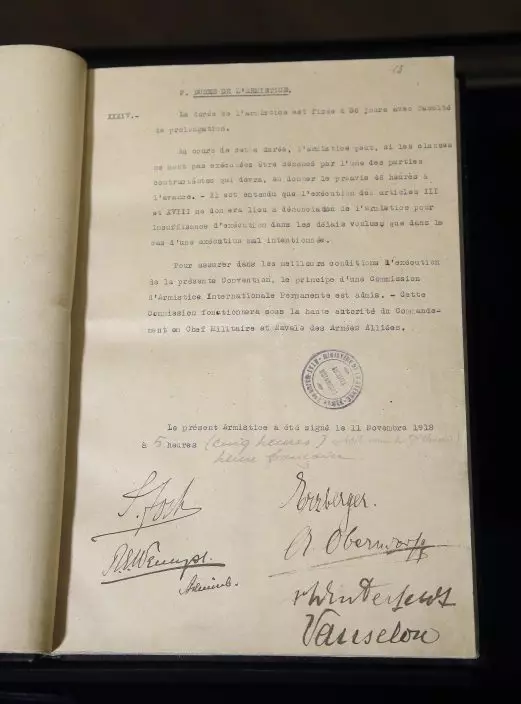

This Tuesday, Oct. 30, 2018 photo shows the Armistice document signed by the Allies and the Germans in a carriage in Rethondes, north of Paris, at 05:00 am on Nov. 11, 1918. The document is displayed at the Vincennes castle museum in Vincennes, outside Paris, France. The Allies signed the Armistice on Nov. 11, 1918 in a train carriage in Compiegne, north of Paris, that ended hostilities with Germany and put an end to the atrocities of World War I. (AP PhotoMichel Euler)

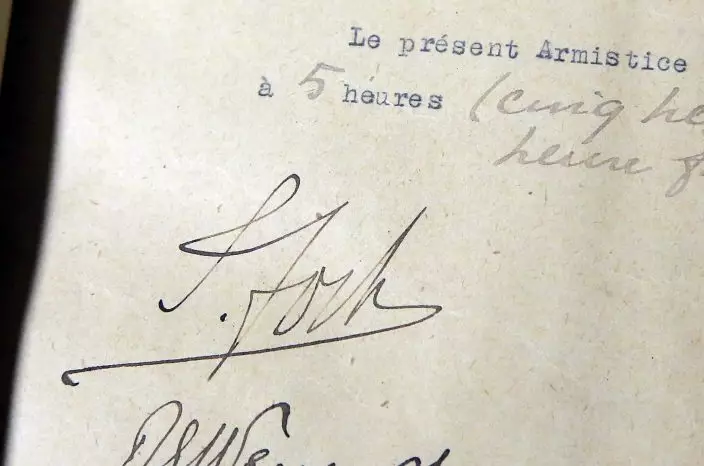

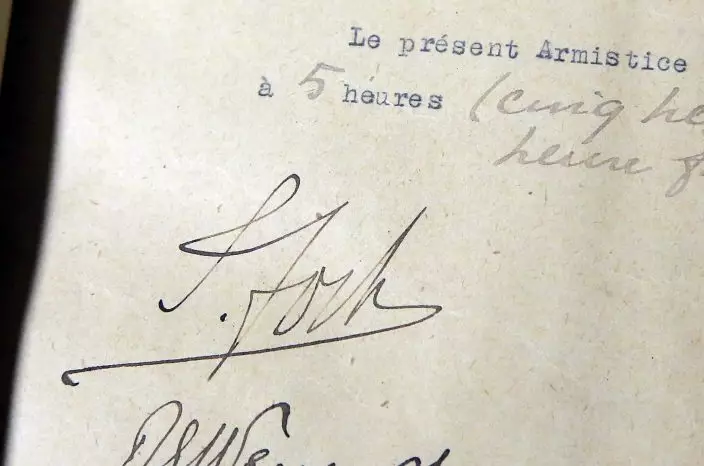

This Tuesday, Oct. 30, 2018 picture shows a close view of the signature of French Marshal Ferdinand Foch on the armistice document signed by the Allies and the Germans in a carriage in Rethondes, north of Paris, at 05:00 am on Nov. 11, 1918. The document is displayed at the Vincennes castle museum in Vincennes, outside Paris, France. The Allies signed the Armistice on Nov. 11, 1918 in a train carriage in Compiegne, north of Paris, that ended hostilities with Germany and put an end to the atrocities of World War I. (AP PhotoMichel Euler)

FILE - This March 24, 1941 file photo shows the saloon car of Compiegne, in where the armistice ending World War I was signed on Nov. 11, 1918. The French and German leaders this weekend will jointly visit the remains of the train carriage where the armistice ending World War I was signed on Nov. 11, 1918. For the French, the dining car became a shrine to peace. For Adolf Hitler, it was a symbol of the humiliation of surrender. The Nazi leader had it dragged to Germany after conquering France in World War II. (AP Photo)

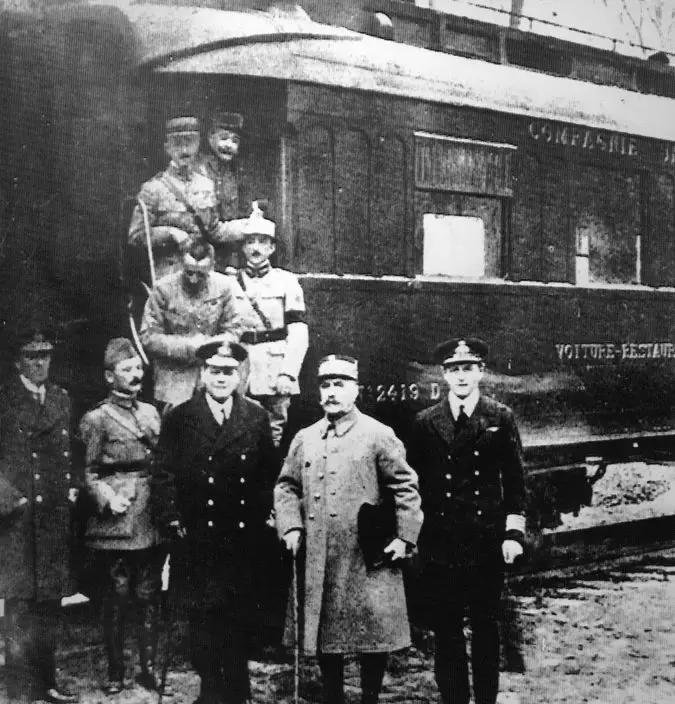

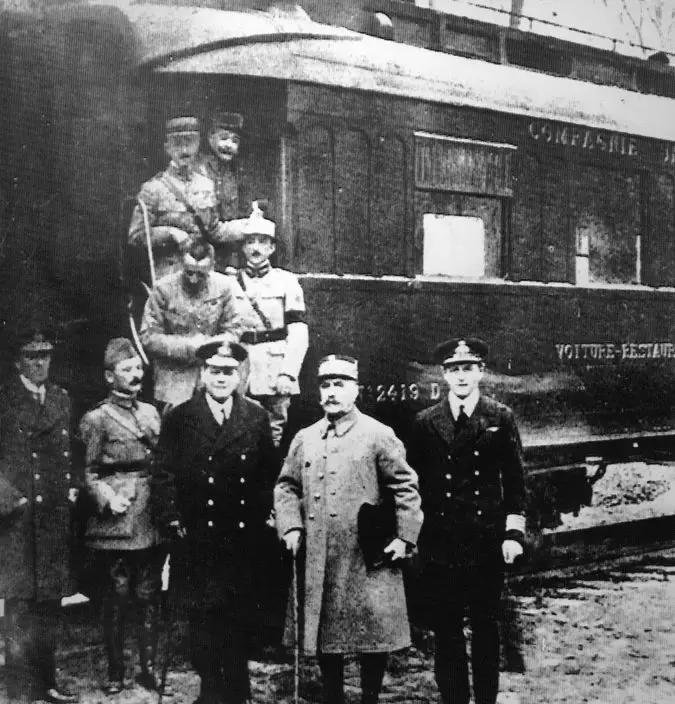

FILE - This undated file photo shows the train wagon in which the armistice of 1918 ending World War I was signed on Nov. 11, 1918, in Rethondes, north of Paris. Standing in front of the train are the most important members of the armistice, Marshal Ferdinand Foch, second right, and General Maxime Weygand, second left. For the French, the dining car became a shrine to peace. For Adolf Hitler, it was a symbol of the humiliation of surrender. The Nazi leader had it dragged to Germany after conquering France in World War II. (AP Photo)

FILE - In this June, 21 1940 file photo, representatives of Germany with Adolf Hitler, seated second left, and France meet at Compiegne Forest, France, in the railroad dining car to discuss terms during World War II. The French and German leaders this weekend will jointly visit the remains of the train carriage where the armistice ending World War I was signed on Nov. 11, 1918. For the French, the dining car became a shrine to peace. For Adolf Hitler, it was a symbol of the humiliation of surrender. The Nazi leader had it dragged to Germany after conquering France in World War II. (AP Photo)

FILE - Adolf Hitler, right, at Compiegne in 1940 after dictating terms to France for their surrender, in Compiegne, north of Paris. The French and German leaders this weekend will jointly visit the remains of the train carriage where the armistice ending World War I was signed on Nov. 11, 1918. For the French, the dining car became a shrine to peace. For Adolf Hitler, it was a symbol of the humiliation of surrender. The Nazi leader had it dragged to Germany after conquering France in World War II. (AP Photo)

This Tuesday, Oct. 30, 2018 photo shows the Armistice document signed by the Allies and the Germans in a carriage in Rethondes, north of Paris, at 05:00 am on Nov. 11, 1918. The document is displayed at the Vincennes castle museum in Vincennes, outside Paris, France. The Allies signed the Armistice on Nov. 11, 1918 in a train carriage in Compiegne, north of Paris, that ended hostilities with Germany and put an end to the atrocities of World War I. (AP PhotoMichel Euler)

This Tuesday, Oct. 30, 2018 picture shows a close view of the signature of French Marshal Ferdinand Foch on the armistice document signed by the Allies and the Germans in a carriage in Rethondes, north of Paris, at 05:00 am on Nov. 11, 1918. The document is displayed at the Vincennes castle museum in Vincennes, outside Paris, France. The Allies signed the Armistice on Nov. 11, 1918 in a train carriage in Compiegne, north of Paris, that ended hostilities with Germany and put an end to the atrocities of World War I. (AP PhotoMichel Euler)

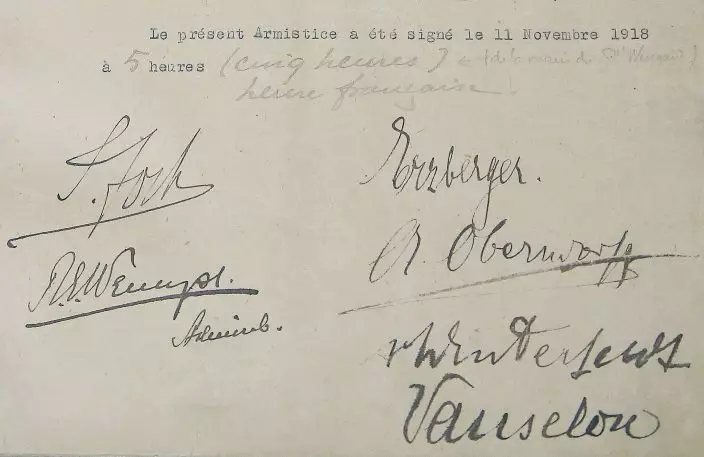

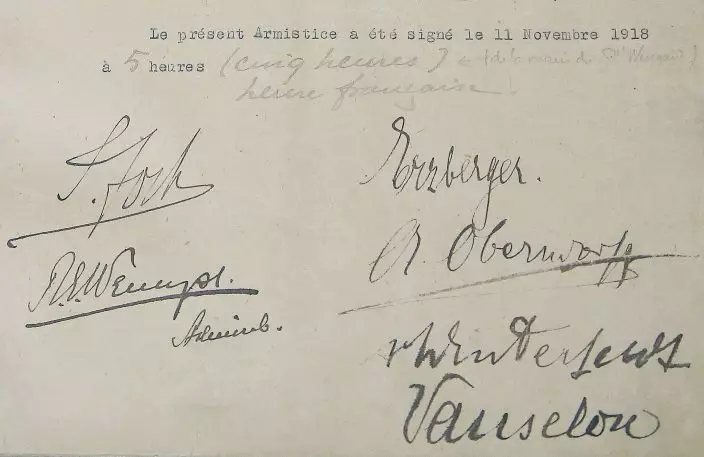

This Tuesday, Oct. 30, 2018 picture shows the signatures of the Allies and Germans on the armistice document dated Nov. 11, 1918 and displayed at the Vincennes castle museum in Vincennes, outside Paris. On left from top : French Marshal Ferdinand Foch and below : British Admiral Lord Wester Wemyss. The German signatures on the right, from the top : Matthias Erzberger head of the German delegation and member of the parliament, Count Alfred von Oberndorff representative of the minister of foreign affair of Germany, General Detlof von Winterfeldt and Captain Ernst Vanselow representing the German Navy. In addition to the signatures the text above reads in French: "The present armistice was signed on Nov. 11, 1918 at 05:00 am French time". (AP PhotoMichel Euler)

This Oct. 19, 2018 photo shows the interior of the train carriage in which the armistice of the Nov. 11, 1918 was signed, in the forest of Compiegne, north of Paris. The French and German leaders this weekend will jointly visit the remains of the train carriage where the armistice ending World War I was signed on Nov. 11, 1918. For the French, the dining car became a shrine to peace. For Adolf Hitler, it was a symbol of the humiliation of surrender. The Nazi leader had it dragged to Germany after conquering France in World War II. (AP PhotoThibault Camus)

This Oct. 19, 2018 photo shows a model depicting the circumstances of the signing of the armistice on Nov. 11, 1918, in the forest of Compiegne, north of Paris. The French and German leaders this weekend will jointly visit the remains of the train carriage where the armistice ending World War I was signed on Nov. 11, 1918. For the French, the dining car became a shrine to peace. For Adolf Hitler, it was a symbol of the humiliation of surrender. The Nazi leader had it dragged to Germany after conquering France in World War II. (AP PhotoThibault Camus)

This Oct. 19, 2018 photo shows the museum of the Nov. 11, 1918 armistice in Compiegne, north of Paris. The French and German leaders this weekend will jointly visit the remains of the train carriage where the armistice ending World War I was signed on Nov. 11, 1918. For the French, the dining car became a shrine to peace. For Adolf Hitler, it was a symbol of the humiliation of surrender. The Nazi leader had it dragged to Germany after conquering France in World War II. (AP PhotoThibault Camus)

This Oct. 19, 2018 photo shows the exact location where the Nov. 11, 1918 armistice was been signed in the forest of Compiegne, north of Paris. The French and German leaders this weekend will jointly visit the remains of the train carriage where the armistice ending World War I was signed on Nov. 11, 1918. For the French, the dining car became a shrine to peace. For Adolf Hitler, it was a symbol of the humiliation of surrender. The Nazi leader had it dragged to Germany after conquering France in World War II. (AP PhotoThibault Camus)

This Oct. 19, 2018 photo shows the museum of the Nov. 11, 1918 armistice, in the forest of Compiegne, north of Paris. The French and German leaders this weekend will jointly visit the remains of the train carriage where the armistice ending World War I was signed on Nov. 11, 1918. For the French, the dining car became a shrine to peace. For Adolf Hitler, it was a symbol of the humiliation of surrender. The Nazi leader had it dragged to Germany after conquering France in World War II. (AP PhotoThibault Camus)

This time, Merkel will have the French president by her side as she visits what remains of the Wagon of Compiegne, the carriage-turned-office where the Allies and Germany signed the armistice on Nov. 11, 1918.

FILE - This March 24, 1941 file photo shows the saloon car of Compiegne, in where the armistice ending World War I was signed on Nov. 11, 1918. The French and German leaders this weekend will jointly visit the remains of the train carriage where the armistice ending World War I was signed on Nov. 11, 1918. For the French, the dining car became a shrine to peace. For Adolf Hitler, it was a symbol of the humiliation of surrender. The Nazi leader had it dragged to Germany after conquering France in World War II. (AP Photo)

An unusual journey took Wagons-Lits Co. carriage 2419D from serving sauteed veal and boeuf bourguignon to passengers in the seaside town of Deauville to serving as a crucible for world peace while stopped in the middle of a forest in Compiegne.

Puzzled tourists often ask Bernard Letemps, the curator of the Armistice Museum, why the Allies signed the cease-fire agreement that ended the atrocities of the Western Front in that humble setting instead of a grand military building or a glittering palace.

At the time, the official headquarters in Senlis of the Allied commander, French Marshal Ferdinand Foch, would have been the expected place to sign a cease-fire.

FILE - This undated file photo shows the train wagon in which the armistice of 1918 ending World War I was signed on Nov. 11, 1918, in Rethondes, north of Paris. Standing in front of the train are the most important members of the armistice, Marshal Ferdinand Foch, second right, and General Maxime Weygand, second left. For the French, the dining car became a shrine to peace. For Adolf Hitler, it was a symbol of the humiliation of surrender. The Nazi leader had it dragged to Germany after conquering France in World War II. (AP Photo)

But the town had endured a brutal German assault. Its inhabitants were taken hostage and its mayor shot in September 1914, before the first Battle of the Marne. How the bruised townspeople would react to the presence of a German delegation, even one coming with the goal of peace, was a serious concern.

"It was out of the question to receive the plenipotentiary Germans in (such a) town," Letemps said.

A moveable train carriage in the nearby Compiegne forest was deemed ideal: The isolated location would deter intruders and the calm and secrecy offered a measure of respect to the defeated Germans.

FILE - In this June, 21 1940 file photo, representatives of Germany with Adolf Hitler, seated second left, and France meet at Compiegne Forest, France, in the railroad dining car to discuss terms during World War II. The French and German leaders this weekend will jointly visit the remains of the train carriage where the armistice ending World War I was signed on Nov. 11, 1918. For the French, the dining car became a shrine to peace. For Adolf Hitler, it was a symbol of the humiliation of surrender. The Nazi leader had it dragged to Germany after conquering France in World War II. (AP Photo)

As it happened, Foch had fitted out a mobile office just the month before — a dining car chosen at random from the French passenger train fleet. And so 2419D became known as the "Wagon of Compiegne."

The Armistice was signed just after 5 a.m., but officials held out six hours to put it into effect out of a sense of poetry — the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month in 1918. That delay, rather unpoetically, cost lives on both sides at the end of a war that had already left 17 million dead.

"The train car represents the end of fighting. The end, when people found peace," Letemps said.

FILE - Adolf Hitler, right, at Compiegne in 1940 after dictating terms to France for their surrender, in Compiegne, north of Paris. The French and German leaders this weekend will jointly visit the remains of the train carriage where the armistice ending World War I was signed on Nov. 11, 1918. For the French, the dining car became a shrine to peace. For Adolf Hitler, it was a symbol of the humiliation of surrender. The Nazi leader had it dragged to Germany after conquering France in World War II. (AP Photo)

He added, smiling: "It fulfilled its role of dining car before becoming famous."

The Armistice Museum lays on the train tracks on the site of the signing in the middle of forest.

Foch was immortalized in statues ubiquitous across France and gave his name to one of the broad, leafy avenues radiating out from the Arc de Triomphe.

This Tuesday, Oct. 30, 2018 photo shows the Armistice document signed by the Allies and the Germans in a carriage in Rethondes, north of Paris, at 05:00 am on Nov. 11, 1918. The document is displayed at the Vincennes castle museum in Vincennes, outside Paris, France. The Allies signed the Armistice on Nov. 11, 1918 in a train carriage in Compiegne, north of Paris, that ended hostilities with Germany and put an end to the atrocities of World War I. (AP PhotoMichel Euler)

The same reception was not reserved for the losing side: One of the Germans to sign the document, Matthias Erzberger, was vilified for his role in the surrender. He was assassinated in 1921.

The story of dining car 2419D and Compiegne didn't end with the war.

For throngs of French mourners in the post-war years, the dining car became a shrine to peace and catharsis.

This Tuesday, Oct. 30, 2018 picture shows a close view of the signature of French Marshal Ferdinand Foch on the armistice document signed by the Allies and the Germans in a carriage in Rethondes, north of Paris, at 05:00 am on Nov. 11, 1918. The document is displayed at the Vincennes castle museum in Vincennes, outside Paris, France. The Allies signed the Armistice on Nov. 11, 1918 in a train carriage in Compiegne, north of Paris, that ended hostilities with Germany and put an end to the atrocities of World War I. (AP PhotoMichel Euler)

The car was taken to Paris for display in the courtyard of the Invalides, the final resting place of Napoleon, before it went back to Compiegne in 1927 to sit in a specially-made memorial constructed on the site of today's museum.

Letemps said the wagon received over 190,000 visitors in one year alone in the 1930s as it became a focus for mourning France's 1.4 million fallen soldiers.

For Hitler in those same years, it became a rallying cry during his ascent to power as he exploited the German public's contempt for the punitive terms of surrender.

This Tuesday, Oct. 30, 2018 picture shows the signatures of the Allies and Germans on the armistice document dated Nov. 11, 1918 and displayed at the Vincennes castle museum in Vincennes, outside Paris. On left from top : French Marshal Ferdinand Foch and below : British Admiral Lord Wester Wemyss. The German signatures on the right, from the top : Matthias Erzberger head of the German delegation and member of the parliament, Count Alfred von Oberndorff representative of the minister of foreign affair of Germany, General Detlof von Winterfeldt and Captain Ernst Vanselow representing the German Navy. In addition to the signatures the text above reads in French: "The present armistice was signed on Nov. 11, 1918 at 05:00 am French time". (AP PhotoMichel Euler)

The Nazi leader visited the site in 1940 when his armies conquered France.

The Fuhrer ordered the dining car brought out of the memorial and returned to the tracks in the spot in the forest it occupied in 1918.

What ensued was Hitler's surreal theatrical restaging of the 1918 armistice, one of history's most famous events, with literally the tables' turned.

This Oct. 19, 2018 photo shows the interior of the train carriage in which the armistice of the Nov. 11, 1918 was signed, in the forest of Compiegne, north of Paris. The French and German leaders this weekend will jointly visit the remains of the train carriage where the armistice ending World War I was signed on Nov. 11, 1918. For the French, the dining car became a shrine to peace. For Adolf Hitler, it was a symbol of the humiliation of surrender. The Nazi leader had it dragged to Germany after conquering France in World War II. (AP PhotoThibault Camus)

The 1940 Armistice was dictated in that train — with Germany the victor and France the loser.

"General (Wilhelm) Keitel read the conditions for the Armistice in the car, with Chancellor Hitler sitting in the place of Marshal Foch," Letemps said.

Hitler then ordered the car to be hauled to Germany and displayed, like a notorious prisoner of war, at the Berlin Cathedral.

This Oct. 19, 2018 photo shows a model depicting the circumstances of the signing of the armistice on Nov. 11, 1918, in the forest of Compiegne, north of Paris. The French and German leaders this weekend will jointly visit the remains of the train carriage where the armistice ending World War I was signed on Nov. 11, 1918. For the French, the dining car became a shrine to peace. For Adolf Hitler, it was a symbol of the humiliation of surrender. The Nazi leader had it dragged to Germany after conquering France in World War II. (AP PhotoThibault Camus)

The dining car was destroyed at the end of World War II, though how that happened has been lost to time. Some accounts blame members of the Nazi SS, others a random airstrike.

In 1950, French manufacturer Wagons-Lits, the company that ran the Orient Express, donated a car from the same series to the museum — 2439D is identical to its ravaged twin from its polished wooden finishes to its studded, leather-bound chairs. It is parked beside the display of the original car remains: a few fragments of bronze decoration and two access ramps.

On Saturday, Merkel becomes the first German chancellor in 78 years to visit the forest clearing where the end of the globe's first conflict was written.

This Oct. 19, 2018 photo shows the museum of the Nov. 11, 1918 armistice in Compiegne, north of Paris. The French and German leaders this weekend will jointly visit the remains of the train carriage where the armistice ending World War I was signed on Nov. 11, 1918. For the French, the dining car became a shrine to peace. For Adolf Hitler, it was a symbol of the humiliation of surrender. The Nazi leader had it dragged to Germany after conquering France in World War II. (AP PhotoThibault Camus)

She will be joined by French President Emmanuel Macron in a scene reminiscent of 1984 when Chancellor Helmut Kohl poignantly held President Francois Mitterrand's hand at an ossuary near Verdun.

On the centenary of the conflict's end, this visit will make for soul-searing images of its own.

Thomas Adamson can be followed at Twitter.com/ThomasAdamson_K

This Oct. 19, 2018 photo shows the exact location where the Nov. 11, 1918 armistice was been signed in the forest of Compiegne, north of Paris. The French and German leaders this weekend will jointly visit the remains of the train carriage where the armistice ending World War I was signed on Nov. 11, 1918. For the French, the dining car became a shrine to peace. For Adolf Hitler, it was a symbol of the humiliation of surrender. The Nazi leader had it dragged to Germany after conquering France in World War II. (AP PhotoThibault Camus)

This Oct. 19, 2018 photo shows the museum of the Nov. 11, 1918 armistice, in the forest of Compiegne, north of Paris. The French and German leaders this weekend will jointly visit the remains of the train carriage where the armistice ending World War I was signed on Nov. 11, 1918. For the French, the dining car became a shrine to peace. For Adolf Hitler, it was a symbol of the humiliation of surrender. The Nazi leader had it dragged to Germany after conquering France in World War II. (AP PhotoThibault Camus)

DUBAI, United Arab Emirates (AP) — He has been in exile for nearly 50 years. His father, Iran’s shah, was so widely hated that millions took to the streets in 1979, forcing him from power. Nevertheless, Iran’s Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi is trying to position himself as a player in his country’s future.

Pahlavi successfully spurred protesters onto the streets Thursday night in a massive escalation of the protests sweeping Iran. Initially sparked by the Islamic Republic’s ailing economy, the demonstrations have become a serious challenge to its theocracy, battered by years of nationwide protests and a 12-day war in June launched by Israel that saw the U.S. bomb nuclear enrichment sites.

What is unknown is how much real support the 65-year-old Pahlavi, who is in exile in the U.S., has in his homeland. Do protesters want a return of the Peacock Throne, as his father’s reign was known? Or are the protesters just looking for anything that is not Iran’s Shiite theocracy?

Pahlavi issued calls, rebroadcast by Farsi-language satellite news channels and websites abroad, for Iranians to return to the streets Friday night, which they did. He has called for further demonstrations this weekend.

“Over the past decade, Iran’s protest movement and dissident community have been increasingly nationalist in tone and tenor,” said Behnam Ben Taleblu, an Iran expert with the Washington-based Foundation for Defense of Democracies, which faces sanctions from Tehran.

“The more the Islamic Republic has failed, the more it has emboldened its antithesis," Taleblu said. "The success of the crown prince and his team has been in drawing a sharp contrast between the normalcy of what was and the promise of what could be, versus the nightmare and present predicament that is the reality for so many Iranians.”

Pahlavi’s profile rose again during U.S. President Donald Trump's first term. Still, Trump and other world leaders have been hesitant to embrace him, given the many cautionary tales in the Middle East and elsewhere of Western governments putting their faith in exiles long estranged from their homelands.

Iranian state media, which for years mocked Pahlavi as being out of touch and corrupt, blamed “monarchist terrorist elements” for the demonstrations Thursday night during which vehicles were burned and police kiosks attacked.

Born Oct. 31, 1960, Pahlavi lived in a gilded world of luxury as the crown prince to Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.

Mohammed Reza had inherited the throne from his own father, an army officer who seized power with support from the British. Mohammed Reza’s rule was cemented by a 1953 CIA-backed coup, and he cooperated closely with the Americans, who sold the autocratic ruler billions of dollars of weapons and spied on the Soviet Union from Iran.

The young Pahlavi was schooled at the eponymous Reza Pahlavi School, set up within the walls of Niavaran Palace in northern Tehran. A biographer of his father noted the crown prince once played rock music in the palace during a New Year’s Eve visit to Tehran by then-U.S. President Jimmy Carter.

But the fall of the Peacock Throne loomed.

While successfully riding rising oil prices in the 1970s, deep economic inequality set in during the shah’s rule and his feared SAVAK intelligence agency became notorious for the torture of dissidents.

Millions across the country participated in protests against the shah, uniting secular leftists, labor unions, professionals, students and Muslim clergy. As the crisis reached a fever pitch, the shah was doomed by his inability to act and poor decisions while secretly fighting terminal cancer.

In 1978, Crown Prince Reza left his homeland for flight school at a U.S. air base in Texas. A year later, his father fled Iran during the onset of what became known as the Islamic Revolution. Shiite clerics squeezed out other anti-shah factions, establishing a new theocratic government that executed thousands after the revolution and to this day remains one of the world’s top executioners.

After his father’s death, a royal court in exile announced that Reza Pahlavi assumed the role of the shah on Oct. 31, 1980, his 20th birthday.

“I can understand and sympathize with your sufferings and your inner torment,” Pahlavi said, addressing Iranians in a speech at the time. “I shed the tears which you must hide. Yet there is, I am sure, light beyond the darkness. Deep in your hearts, you may be confident that this nightmare, like others in our history, will pass.”

But what followed has been nearly five decades in exile.

Pahlavi attempted to gain influence abroad. In 1986, The Washington Post reported that the CIA supplied the prince’s allies “a miniaturized television transmitter for an 11-minute clandestine broadcast” to Iran by Pahlavi that pirated the signal of two stations in the Islamic Republic.

“I will return and together we will pave the way for the nation’s happiness and prosperity through freedom,” Pahlavi reportedly said in the broadcast.

That did not happen. Pahlavi largely lived abroad in the United States in Los Angeles and Washington, D.C., while his mother, the Shahbanu Farah Pahlavi, lived in Paris.

Circles of diehard Iranian monarchists in exile have long touted dreams of the Pahlavi dynasty returning to power. But Pahlavi has been hampered in gaining wider appeal by a number of factors: bitter memories of his father’s rule; the perception that he and his family are out of touch with their homeland; and repression inside Iran that aims to silence any opposition sentiment.

At the same time, younger generations in Iran born decades after the shah’s rule ended have grown up under a different experience; social restrictions and brutal suppression by the Islamic Republic and economic turmoil under international sanctions, corruption and mismanagement.

Pahlavi has sought to have a voice through social media videos, and Farsi-language news channels such as Iran International have highlighted his calls for protests. The channel also aired QR codes that led to information for security force members within Iran who want to cooperate with him.

Mahmood Enayat, the general manager of Iran International's owner Volant Media, said the channel ran Pahlavi's ad and others “on a pro bono basis" as “part of our mission to support Iran’s civil society.”

In interviews in recent years, Pahlavi has raised the idea of a constitutional monarchy, perhaps with an elected rather than a hereditary ruler. But he has also said it is up to Iranians to choose.

“This regime is simply irreformable because the nature of it, its DNA, is such that it cannot,” Pahlavi told The Associated Press in 2017. “People have given up with the idea of reform and they think there has to be fundamental change. Now, how this change can occur is the big question.”

He has also faced criticism for his support of and from Israel, particularly after the June war. Pahlavi traveled to Israel in 2023 and met Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, a longtime hawk on Iran whose criticism of the 2015 Iran nuclear deal fueled Trump's decision to withdraw America from the accord. Netanyahu also oversaw the 12-day war with Iran.

“My focus right now is on liberating Iran, and I will find any means that I can, without compromising the national interests and independence, with anyone who is willing to give us a hand, whether it is the U.S. or the Saudis or the Israelis or whomever it is,” he said in 2017.

FILE - Reza Pahlavi, the son of Iran's toppled Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, speaks during a news conference, June 23, 2025 in Paris. (AP Photo/Thomas Padilla, File)