Growing up as a transgender child in Chile, Angela was so desperate to escape the physical and verbal abuse from other students at her elementary school that she thought about taking her own life.

"I just wanted to die," said the now 16-year-old. "I didn't want to exist, because what they did to me made me feel awful."

Click to Gallery

In this Dec.14, 2018 photo, transgender girls Angela, top left, plays with schoolmate Laura, as Violeta, right, sits next to them during a class break at the Amaranta Gomez school in Santiago, Chile. Although space is limited at the school, parents say students have regained their confidence: They seem happier, more relaxed and eager to participate in class. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

In this Dec.15, 2018 photo, accompanied by her sisters, at right, Emma a transgender girl, left, a student of the Amaranta Gomez school, updates her identity card information in the national registry of persons, in Santiago, Chile. In recent years, the families of trans children have demanded greater acceptance, a call that recently led to the approval of a law that allows people over the age of 14 to change their name and gender in official records with the consent of their parents or legal guardians. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

In this Dec.12, 2018 photo, transgender children participate in a class at the Amaranta Gomez school, in Santiago, Chile. Teachers work pro bono, but all other expenses for the school's first year were funded by Selenna Foundation President Evelyn Silva and school coordinator Ximena Maturana out of their personal savings. Starting in March, families will have to pay about $7 a month for each child. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

In this Dec.12, 2018 photo, transgender children embrace teacher Teani Cortes during the last day of school at the Amaranta Gomez school in Santiago, Chile. The institution, founded by the Chile-based Selenna Foundation that protects their rights, is a milestone in a socially conservative country. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

In this Dec.12, 2018 photo, transgender girls plays with a doll at the Amaranta Gomez school in Santiago, Chile. Although space is limited, parents say students have regained their confidence: They seem happier, more relaxed and eager to participate in class. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

In this Dec.13, 2018 photo, transgender student Laura, left, enters a classroom at the Amaranta Gomez school in Santiago, Chile. Students agreed that the school has helped them fully embrace their identity. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

In this Dec.14, 2018 photo, transgender girls Angela, top left, plays with schoolmate Laura, as Violeta, right, sits next to them during a class break at the Amaranta Gomez school in Santiago, Chile. Although space is limited at the school, parents say students have regained their confidence: They seem happier, more relaxed and eager to participate in class. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

In this Dec. 11, 2018 photo, Violeta, a transgender girl, jumps during recess at the Amaranta Gomez school in Santiago, Chile. Students agreed that the school has helped them fully embrace their identity. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

In this Dec.13, 2018 photo, Laura, a transgender girl, looks from behind a glass door during recess at the Amaranta Gomez school in Santiago, Chile. The school was launched in 2017 as a way to help families of trans children, who often skip classes or even fail to finish their studies as result of discrimination, said Selenna Foundation President Evelyn Silva. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

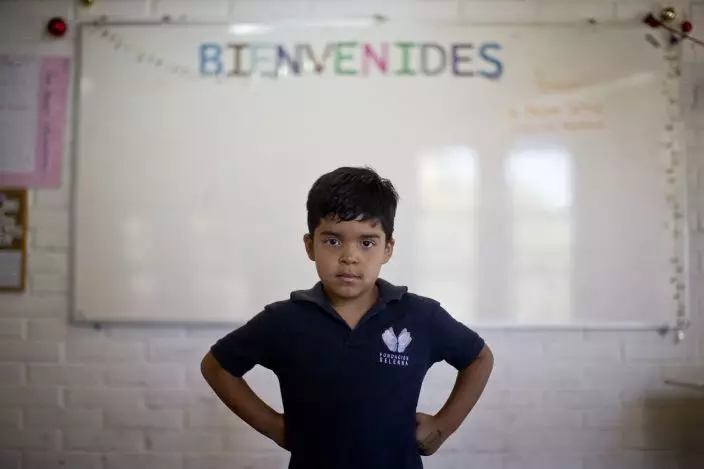

In this Dec.12, 2018 photo, Alexis, a transgender boy, poses for a photo at the Amaranta Gomez school in Santiago, Chile. "I'm happy here because there are many other kids just like me," said Alexis, who also said that he was constantly bullied at his previous school. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

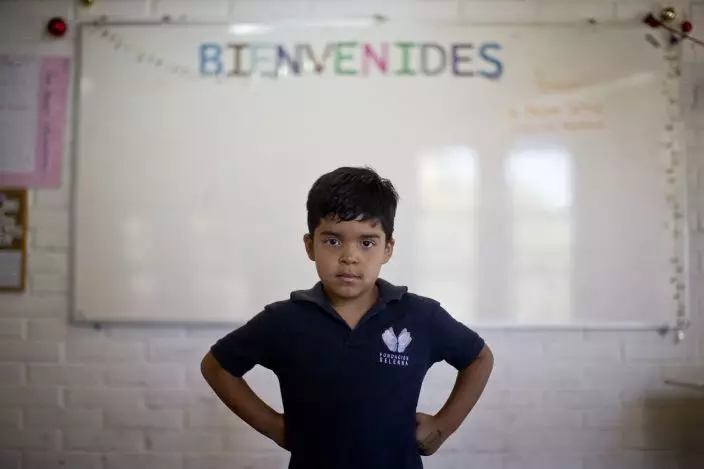

In this Dec.14, 2018 photo, Angela, a transgender girl, poses for a photo at the Amaranta Gomez school in Santiago, Chile. Growing up as a transgender child in Chile, Angela was so desperate to escape the physical and verbal abuse from other students at her elementary school that she thought about taking her own life. Now she has found hope at the Amaranta Gomez school, Latin America’s first school for trans children. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

In this Dec.14, 2018 photo, Constanza, a transgender girl, poses for a photo at the Amaranta Gomez school in Santiago, Chile. Since its start, school attendance has grown from the original five students to 22 in December, and six more have already enrolled for this year. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

In this Dec.14, 2018 photo, Angela, a transgender girl, poses for a photo at the Amaranta Gomez school in Santiago, Chile. Students at the school are assigned to one of two classrooms based on age. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

In this Dec.18, 2018 photo, transgender children prepare to attend the graduation ceremony at the Amaranta Gomez school in Santiago, Chile. Since its start, school attendance has grown from the original five students to 22 in December, and six more have already enrolled for this year. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

In this Dec.18, 2018 photo, Angela, a transgender girl, is given a "Best Effort" medal during the Amaranta Gomez school graduation ceremony, in Santiago, Chile. Despite the lack of resources, the foundation has started a summer school that offers dance and other workshops for about 20 children, including some who are not attending the school. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

In this Dec.18, 2018 photo, transgender student Sebastian, center, carries his diploma after his graduation ceremony at the Amaranta Gomez school in Santiago, Chile. Classes began in April 2018 at a spaced loaned by a community center in the Chilean capital of Santiago. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

In this Dec.15, 2018 photo, accompanied by her sisters, at right, Emma a transgender girl, left, a student of the Amaranta Gomez school, updates her identity card information in the national registry of persons, in Santiago, Chile. In recent years, the families of trans children have demanded greater acceptance, a call that recently led to the approval of a law that allows people over the age of 14 to change their name and gender in official records with the consent of their parents or legal guardians. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

In this Dec.13, 2018 photo, Aurora, a transgender girl, does cartwheels in the Amaranta Gomez school, in Santiago, Chile. Activists and parents of transgender children say that's the stage of childhood or pre-adolescence when children discover that their gender does not correspond to their body. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

After suffering years of discrimination, Angela and some 20 other transgender minors aged 6 to 17 have found hope at Latin America's first school for trans children . The institution, founded by the Chile-based Selenna Foundation that protects their rights, is a milestone in a country that was so socially conservative that it only legalized divorce in 2004.

In this Dec.12, 2018 photo, transgender children participate in a class at the Amaranta Gomez school, in Santiago, Chile. Teachers work pro bono, but all other expenses for the school's first year were funded by Selenna Foundation President Evelyn Silva and school coordinator Ximena Maturana out of their personal savings. Starting in March, families will have to pay about $7 a month for each child. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

In recent years, the families of trans children have demanded greater acceptance — a call that recently led to the approval of a law that allows people over the age of 14 to change their name and gender in official records with the consent of their parents or legal guardians.

Activists and parents of transgender children say that's the stage of childhood or pre-adolescence when children discover that their gender does not correspond to their body.

A 2016 report by UNESCO said that in Latin America, as in the rest of the world, violence against sexual orientation or gender identity in schools wreaks "havoc on the development of the affected people, school coexistence, academic performance and, consequently, their permanence in school."

In this Dec.12, 2018 photo, transgender children embrace teacher Teani Cortes during the last day of school at the Amaranta Gomez school in Santiago, Chile. The institution, founded by the Chile-based Selenna Foundation that protects their rights, is a milestone in a socially conservative country. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

Chile has slowly shifted its conservative stands on social issues. In 2012, it passed an anti-discrimination law and in 2017, it ended its absolute ban on abortion, legalizing it in when a woman's life is in danger, a fetus is not viable and in cases of rape. The shift has been accelerated by a clerical sex abuse scandal.

The school was launched in 2017 as a way to help families of trans children, who often skip classes or even fail to finish their studies as result of discrimination, said Selenna Foundation President Evelyn Silva. Classes began in April 2018 in a space loaned by a community center in the Chilean capital of Santiago. Courses include math, science, history and English, as well as workshops on art and photography.

Since its start, school attendance has grown from the original five students to 22 in December, and six more have already enrolled in the new year. Students are assigned to one of two classrooms based on age.

In this Dec.12, 2018 photo, transgender girls plays with a doll at the Amaranta Gomez school in Santiago, Chile. Although space is limited, parents say students have regained their confidence: They seem happier, more relaxed and eager to participate in class. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

"I'm happy here because there are many other kids just like me," said Alexis, a 6-year-old student, who also said that he was constantly bullied at his previous school.

Teachers work pro bono, but all other expenses for the school's first year were funded by Silva and school coordinator Ximena Maturana out of their personal savings. Starting in March, families will have to pay about $7 a month for each child.

"We try to reduce the costs to the minimum (for families) so that they don't say that (kids) are not attending because they don't have pencils, and it becomes a reason to leave school," Silva said.

In this Dec.13, 2018 photo, transgender student Laura, left, enters a classroom at the Amaranta Gomez school in Santiago, Chile. Students agreed that the school has helped them fully embrace their identity. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

Despite the lack of resources, the foundation has started a summer school that offers dance and other workshops for about 20 children, including some who are not attending the school.

Although space is limited, parents say students have regained their confidence: They seem happier, more relaxed and eager to participate in class.

"(My son) was losing his identity, he was getting ashamed of being transgender because he felt that he didn't fit in," said Alexis' father, Gabriel Astete. "He was being forced to go to the boys' bathroom when he wanted to go to one for girls. His self-esteem was very low at the traditional school."

In this Dec.14, 2018 photo, transgender girls Angela, top left, plays with schoolmate Laura, as Violeta, right, sits next to them during a class break at the Amaranta Gomez school in Santiago, Chile. Although space is limited at the school, parents say students have regained their confidence: They seem happier, more relaxed and eager to participate in class. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

Students agreed that the school has helped them fully embrace their identity.

"I feel free and happy here," said Felipe, 15. "The environment is very good. Everyone who arrives is simply accepted."

In this Dec. 11, 2018 photo, Violeta, a transgender girl, jumps during recess at the Amaranta Gomez school in Santiago, Chile. Students agreed that the school has helped them fully embrace their identity. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

In this Dec.13, 2018 photo, Laura, a transgender girl, looks from behind a glass door during recess at the Amaranta Gomez school in Santiago, Chile. The school was launched in 2017 as a way to help families of trans children, who often skip classes or even fail to finish their studies as result of discrimination, said Selenna Foundation President Evelyn Silva. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

In this Dec.12, 2018 photo, Alexis, a transgender boy, poses for a photo at the Amaranta Gomez school in Santiago, Chile. "I'm happy here because there are many other kids just like me," said Alexis, who also said that he was constantly bullied at his previous school. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

In this Dec.14, 2018 photo, Angela, a transgender girl, poses for a photo at the Amaranta Gomez school in Santiago, Chile. Growing up as a transgender child in Chile, Angela was so desperate to escape the physical and verbal abuse from other students at her elementary school that she thought about taking her own life. Now she has found hope at the Amaranta Gomez school, Latin America’s first school for trans children. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

In this Dec.14, 2018 photo, Constanza, a transgender girl, poses for a photo at the Amaranta Gomez school in Santiago, Chile. Since its start, school attendance has grown from the original five students to 22 in December, and six more have already enrolled for this year. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

In this Dec.14, 2018 photo, Angela, a transgender girl, poses for a photo at the Amaranta Gomez school in Santiago, Chile. Students at the school are assigned to one of two classrooms based on age. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

In this Dec.18, 2018 photo, transgender children prepare to attend the graduation ceremony at the Amaranta Gomez school in Santiago, Chile. Since its start, school attendance has grown from the original five students to 22 in December, and six more have already enrolled for this year. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

In this Dec.18, 2018 photo, Angela, a transgender girl, is given a "Best Effort" medal during the Amaranta Gomez school graduation ceremony, in Santiago, Chile. Despite the lack of resources, the foundation has started a summer school that offers dance and other workshops for about 20 children, including some who are not attending the school. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

In this Dec.18, 2018 photo, transgender student Sebastian, center, carries his diploma after his graduation ceremony at the Amaranta Gomez school in Santiago, Chile. Classes began in April 2018 at a spaced loaned by a community center in the Chilean capital of Santiago. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

In this Dec.15, 2018 photo, accompanied by her sisters, at right, Emma a transgender girl, left, a student of the Amaranta Gomez school, updates her identity card information in the national registry of persons, in Santiago, Chile. In recent years, the families of trans children have demanded greater acceptance, a call that recently led to the approval of a law that allows people over the age of 14 to change their name and gender in official records with the consent of their parents or legal guardians. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

In this Dec.13, 2018 photo, Aurora, a transgender girl, does cartwheels in the Amaranta Gomez school, in Santiago, Chile. Activists and parents of transgender children say that's the stage of childhood or pre-adolescence when children discover that their gender does not correspond to their body. (AP PhotoEsteban Felix)

BERLIN (AP) — Erich von Däniken, the Swiss author whose bestselling books about the extraterrestrial origins of ancient civilizations brought him fame among paranormal enthusiasts and scorn from the scientific community, has died. He was 90.

Von Däniken's representatives announced on his website on Sunday that he had died the previous day in a hospital in central Switzerland. His daughter Cornelia confirmed the information to Swiss news agency SDA.

Von Däniken rose to prominence in 1968 with the publication of his first book "Chariots of the Gods," in which he claimed that the Mayans and ancient Egyptians were visited by alien astronauts and instructed in advanced technology that allowed them to build giant pyramids.

The book fueled a growing interest in unexplained phenomena at a time when thanks to conventional science man was about to take its first steps on the Moon.

"Chariots of the Gods" was followed by more than two dozen similar books that sold 60 million copies in 32 languages, spawning a literary niche in which fact and fantasy were mixed together against all historical and scientific evidence.

While von Däniken managed to shrug off his many critics, the former hotel waiter had a troubled relationship with money throughout his life and frequently came close to financial ruin.

Born in 1935, the son of a clothing manufacturer in the northern Swiss town of Schaffhausen, von Däniken is said to have rebelled against his father's strict Catholicism and the priests who instructed him at boarding school by developing his own alternatives to the biblical account of the origins of life.

After leaving school in 1954, von Däniken worked as a waiter and barkeeper for several years, during which he was repeatedly accused of fraud and served a couple of short stints in prison.

In 1964, he was appointed manager of a hotel in the exclusive resort town of Davos and began writing his first book. Its publication and rapid commercial success were quickly followed by accusations of tax dodging and financial impropriety, for which he again spent time behind bars.

By the time he left prison, "Chariots of the Gods" was earning von Däniken a fortune and a second book "Gods from Outer Space" was ready for publication, allowing him to commit himself to his paranormal passion and travel the world in search of new mysteries to uncover.

Throughout the 1970s von Däniken undertook countless field trips to Egypt, India, and above all Latin America, whose ancient cultures held a particular fascination for the amateur archaeologist.

He lectured widely and set up societies devoted to promoting his theories, later pioneering the use of video and multimedia to reach out to ever-larger audiences hungry for a different account of history.

No amount of criticism dissuaded him and his fans from believing that Earth has been visited repeatedly by beings from Outer Space, and will be again in the future.

In 1991 von Däniken gained the damning accolade of being the first recipient of the "Ig Nobel" prize for literature — for raising the public awareness of science through questionable experiments or claims.

Even when confronted with fabricated evidence in a British television documentary — supposedly ancient pots were shown to be almost new — von Däniken insisted that, minor discrepancies aside, his theories were essentially sound.

In 1985 von Däniken wrote "Neue Erinnerungen an die Zukunft" — "New Memories of the Future" — ostensibly to address his many critics: "I have admitted (my mistakes), but not one of the foundations of my theories has yet been brought down."

Although his popularity was waning in the English-speaking world by the 1980s, von Däniken's books and films influenced a wave of semi-serious archaeological documentaries and numerous popular television shows, including "The X-Files," which featured two FBI agents tasked with solving paranormal mysteries.

His last major venture, a theme park based on his books, failed after just a few years due to lack of interest. The "Mystery Park" still stands, its man-made pyramids and otherworldly domes rotting as tourists prefer to explore the charms of the nearby town of Interlaken and the imposing Swiss Alps that surround it.

Erich von Däniken is survived by his wife of 65 years, Elisabeth Skaja, Cornelia and two grandchildren.

FILE - Erich von Daeniken, co-founder and co-owner of Mystery Park, poses in front of the Panorama Tower at Mystery Park in Interlaken, Wednesday, April 23, 2003. (Gaetan Ball)/Keystone via AP, File)