Spain appears to have stemmed a surge in illegal migration that made it Europe's main entry point for sea arrivals, after boosting joint efforts with neighboring Morocco to clamp down on the flow.

Spain, which holds a national election Sunday, saw nearly 60,000 people reach its shores irregularly in 2018, most from Morocco and West Africa. But sea arrivals plummeted in February and since then have remained at the lowest level in two years, Spanish statistics show.

While the migrant flow often fluctuates due to weather and other factors, an internal European Union report obtained by The Associated Press suggests intensified efforts to stop the migrants before they're able to reach European waters are paying off.

FILE - In this June. 28, 2018 file photo, a Guardia Civil officer stands next to Moroccan migrants after they arrived on the beach sailing on a rubber dinghy near Tarifa, in the south of Spain. Spain appears to have stemmed a surge in illegal migration that made it the main Mediterranean entry point for migrants seeking ways into Europe by increasing Morocco's involvement in border control. (AP PhotoEmilio Morenatti, File)

"In the last four months, the increased cooperation between Spanish and Moroccan authorities has significantly contributed to decrease the illegal migratory flows towards Spain," says the report, which was distributed to member states in March.

The report doesn't specify what Morocco did to hold back migrants or what it got in return other than "explicit recognition and support" from the Spanish government and the EU's executive Commission in Brussels.

The EU office dealing with relations with neighboring countries including Morocco declined to comment on the report but noted that the bloc has spent 232 million euros ($262 million) on migration-related projects with Morocco since 2014, mostly in border control and fighting smugglers.

FILE - In this Thursday, June 28, 2018 file photo, a rubber dinghy used by Moroccan migrants is seen near Tarifa, in the south of Spain. Spain appears to have stemmed a surge in illegal migration that made it the main Mediterranean entry point for migrants seeking ways into Europe by increasing Morocco's involvement in border control. (AP PhotoEmilio Morenatti, File)

More recently, Rabat received 36 million of a 148 million-euro emergency package approved by the EU in late 2018 to boost Morocco's capacity to protect vulnerable migrants, address irregular migration and dismantle human smuggling networks.

In an election debate this week, Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez stressed the need to reinforce cooperation with countries of origin and transit on the migrant trail to Europe. "It is what the government of Spain is doing with Morocco and with sub-Saharan countries," he said.

Human rights experts warn that outsourcing Europe's border control to North African countries creates a risk of human right violations. Amnesty International last year denounced a Moroccan crackdown on sub-Saharan migrants, including alleged mass roundups and expulsions without due process.

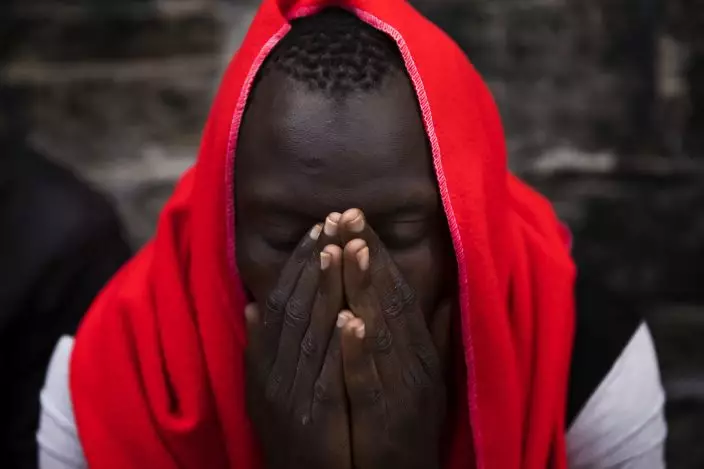

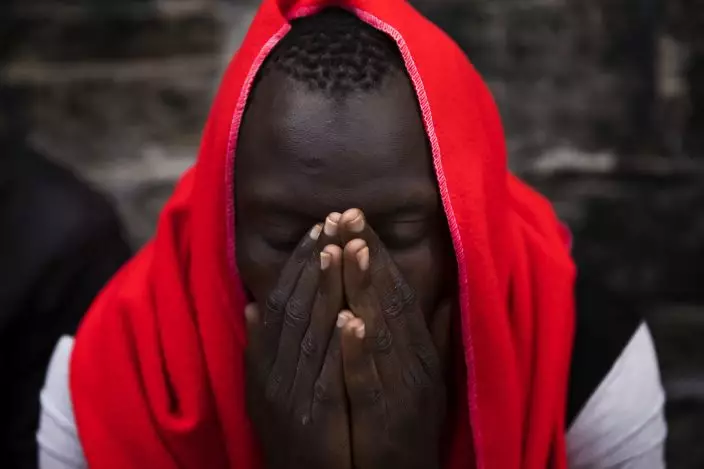

FILE - In this June 27, 2018 file photo, a migrant rests at the port of Tarifa, southern Spain, as he waits to be transported to a police station after being rescued by Spain's Maritime Rescue Service in the Strait of Gibraltar. Spain appears to have stemmed a surge in illegal migration that made it the main Mediterranean entry point for migrants seeking ways into Europe by increasing Morocco's involvement in border control. (AP PhotoEmilio Morenatti, File)

Alarm Phone, a network of activists behind a hotline for migrants in distress at sea, said it believed arrivals are down "due to repressive campaigns in Morocco and political developments in Spain that affect search and rescue operations" in waters around the narrow Strait of Gibraltar that separates the two countries.

In contrast with Italy's hard line on migrants, Sánchez's center-left government initially adopted a welcoming attitude, even granting safe harbor last June to a humanitarian rescue ship that was refused by Italy and Malta.

But as sea arrivals soared and Spain eclipsed Italy and Greece as the top destination for migrants entering Europe irregularly, the government quietly shifted its stance, mindful of the rise of the far-right Vox party, which in December won seats in the legislature of the southern Andalusia region. Vox is polling at over 10 percent ahead of the national election on Sunday.

Spain became reluctant to accept migrant ships from other parts of the Mediterranean and ordered the Spanish Maritime Rescue Service to stop the daily tweeting of migrant rescues off Spanish shores, keeping the subject off the front pages.

The Maritime Rescue Service declined to comment on whether it is also ceding the initiative for rescues to Moroccan authorities, in a break with years of practice. It said only it is in a "project funded by the European Union with the goal of increasing Morocco's capacity of search and rescue."

However, the main union representing Spanish rescuers this week said the Maritime Rescue Service is increasingly instructed to wait and let the Moroccan Coast Guard assist migrant ships in distress, even though it "has few means and limited experience regarding the rescuing of human lives at sea."

In March, 45 people perished as their sinking dinghy waited to be rescued by the Moroccan authorities, 24 hours after the first distress call had been received by Spain. Moroccan vessels have a history of opening fire in attempts to intercept migrant boats, which last year resulted in the death of a 19-year-old woman.

Moroccan authorities did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Overall the migrant flow to Europe has fallen sharply since 2015, when as many as 1 million entered the continent irregularly, mainly from Turkey to Greece. Border control deals struck with Turkey and later with Libya brought levels down considerably.

But traffic on the Western Mediterranean route increased, peaking in October last year with 11,000 sea arrivals in Spain. While numbers typically fall during the winter, they remained relatively high through January when 4,104 arrivals were recorded in Spain, but dropped 77 percent drop to just 936 in February. The number fell further in March, to 588, according to figures compiled by the International Organization for Migration, based on Spanish statistics.

In a written response to AP, Spain's Interior Ministry said "satisfactory cooperation" with Morocco was behind the drop in arrivals, adding it had donated 75 vehicles for Moroccan authorities to use in border control.

The ministry also acknowledged that Spain has acted as an advocate for Moroccan interests in the EU, calling them "fair and fundamental to maintain security and coexistence in the Mediterranean Sea."

Morocco and the EU recently agreed on a revised agriculture deal extending the Kingdom's access to the European market and a controversial fisheries agreement involving disputed waters off the Western Sahara region. The deals were backed by the European Parliament in January and February, respectively.

Meanwhile, Spanish King Felipe VI visited Morocco in February, signing 11 bilateral agreements, including one that reinforced the collaboration between Spain and Morocco to fight terrorism, human trafficking and illegal migration, the Interior Ministry said.

Associated Press writers Aritz Parra in Madrid; Amira El Masaiti in Rabat, Morocco; and Lorne Cook in Brussels contributed to this report.

BRUSSELS (AP) — European Union nations endorsed sweeping reforms to the bloc’s failed asylum system on Tuesday as campaigning for Europe-wide elections next month gathers pace, with migration expected to be an important issue.

EU government ministers approved 10 legislative parts of The New Pact on Migration and Asylum. It lays out rules for the 27 member countries to handle people trying to enter without authorization, from how to screen them to establish whether they qualify for protection to deporting them if they’re not allowed to stay.

Hungary and Poland, which have long opposed any obligation for countries to host migrants or pay for their upkeep, voted against the package but were unable to block it.

Mainstream political parties believe the pact resolves the issues that have divided member nations since well over 1 million migrants swept into Europe in 2015, most fleeing war in Syria and Iraq. They hope the system will starve the far right of vote-winning oxygen in the June 6-9 elections.

However, the vast reform package will only enter force in 2026, bringing no immediate fix to an issue that has fueled one of the EU’s biggest political crises, dividing nations over who should take responsibility for migrants when they arrive and whether other countries should be obligated to help.

Critics say the pact will let nations detain migrants at borders and fingerprint children. They say it’s aimed at keeping people out and infringes on their right to claim asylum. Many fear it will result in more unscrupulous deals with poorer countries that people leave or cross to get to Europe.

Europe’s asylum laws have not been updated for about two decades. The system frayed and then fell apart in 2015. It was based on the premise that migrants should be processed, given asylum or deported in the country they first enter. Greece, Italy and Malta were left to shoulder most of the financial burden and deal with public discontent. Since then, the ID-check-free zone known as the Schengen Area has expanded to 27 countries, 23 of them EU members. It means that more than 400 million Europeans and visitors, including refugees, are able to move without showing travel documents.

Some 3.5 million migrants arrived legally in Europe in 2023. Around 1 million others were on EU territory without permission. Of the latter, most were people who entered normally via airports and ports with visas but didn’t go home when they expired. The pact applies to the remaining minority, estimated at around 300,000 migrants last year. They are people caught crossing an external EU border without permission, such as those reaching the shores of Greece, Italy or Spain via the Mediterranean Sea or Atlantic Ocean on boats provided by smugglers.

The country on whose territory people land will screen them at or near the border. This involves identity and other checks -– including on children as young as 6. The information will be stored on a massive new database, Eurodac. This screening should determine whether a person might pose a health or security risk and their chances of being permitted to stay. Generally, people fleeing conflict, persecution or violence qualify for asylum. Those looking for jobs are likely to be refused entry. Screening is mandatory and should take no longer than seven days. It should lead to one of two things: an application for international protection, like asylum, or deportation to their home country.

People seeking asylum must apply in the EU nation they first enter and stay until the authorities there work out what country should handle their application. It could be that they have family, cultural or other links somewhere else, making it more logical for them to be moved. The border procedure should be done in 12 weeks, including time for one legal appeal if their application is rejected. It could be extended by eight weeks in times of mass movements of people. Procedures could be faster for applicants from countries whose citizens are not often granted asylum. Critics say this undermines asylum law because applicants should be assessed individually, not based on nationality. People would stay in “reception centers” while it happens, with access to health care and education. Those rejected would receive a deportation order.

To speed things up, a deportation order is supposed to be issued automatically when an asylum request is refused. A new 12-week period is foreseen to complete this process. The authorities may detain people throughout. The EU’s border and coast guard agency would help organize joint deportation flights. Currently, less than one in three people issued with an order to leave are deported. This is often due to a lack of cooperation from the countries these people come from.

The new rules oblige countries to help an EU partner under migratory pressure. Support is mandatory, but flexible. Nations can relocate asylum applicants to their territory or choose some other form of assistance. This could be financial -– a relocation is evaluated at 20,000 euros ($21,462) per person -– technical or logistical. Members can also assume responsibility for deporting people from the partner country in trouble.

Two issues stand out: Will member countries ever fully enact the plan, and will the EU’s executive branch, the European Commission, enforce the new rules when it has chosen not to apply the ones already in place? The commission is due to present a Common Implementation Plan by June. It charts a path and timeline to get the pact working over the next two years, with targets that the EU and member countries should reach. Things could get off to a rocky start. Hungary, which has vehemently opposed the reforms, takes over the EU’s agenda-setting presidency for six months on July 1.

Associated Press journalists Renata Brito in Barcelona, Spain, contributed to this report.

Migrants sit on the deck of the Sea Watch-3 rescue ship in the Maltese search and rescue zone of the Mediterranean Sea on Oct. 19, 2021. IEuropean Union nations will discuss on Tuesday, May 14, 2024, sweeping new reforms to the bloc's failed asylum system as campaigning for Europe-wide elections next month gathers pace, with migration expected to be an important issue. (AP Photo/Valeria Mongelli, File)

FILE - Migrants disembark from a Greek coast vessel after a rescue operation, at the port of Mytilene, on the northeastern Aegean Sea island of Lesbos, Greece, Monday, Aug. 28, 2023. European Union nations will discuss on Tuesday, May 14, 2024, sweeping new reforms to the bloc's failed asylum system as campaigning for Europe-wide elections next month gathers pace, with migration expected to be an important issue. (AP Photo/Panagiotis Balaskas, File)

FILE - Two men share a meal in a makeshift tent camp outside the Petit Chateau reception center in Brussels, Tuesday, Jan. 17, 2023. European Union nations will discuss on Tuesday, May 14, 2024, sweeping new reforms to the bloc's failed asylum system as campaigning for Europe-wide elections next month gathers pace, with migration expected to be an important issue. (AP Photo/Olivier Matthys, File)

FILE -Migrants rest on the deck of Sea Watch-3 rescue ship in Maltese SAR zone, Tuesday, Oct. 19, 2021. European Union nations will discuss on Tuesday, May 14, 2024, sweeping new reforms to the bloc's failed asylum system as campaigning for Europe-wide elections next month gathers pace, with migration expected to be an important issue. (AP Photo/Valeria Mongelli, File)

FILE - A cemetery, filled with graves mostly from migrants trying to reach the Greek island of Lesbos, is seen from above at Kato Tritos village on the northeastern Aegean Sea island of Lesbos, Greece, on Wednesday, April 17, 2024. European Union nations will discuss on Tuesday, May 14, 2024, sweeping new reforms to the bloc's failed asylum system as campaigning for Europe-wide elections next month gathers pace, with migration expected to be an important issue. (AP Photo/Panagiotis Balaskas, File)

FILE - Opponents of France's immigration law protest with banners that read, "Freedom, equality, fraternity" and "no to the immigration law" at Trocadero Plaza near Eiffel Tower in Paris, Sunday, Jan. 21, 2024. European Union nations will discuss on Tuesday, May 14, 2024, sweeping new reforms to the bloc's failed asylum system as campaigning for Europe-wide elections next month gathers pace, with migration expected to be an important issue. (AP Photo/Thomas Padilla, File)

FILE - Refugees wait in line at the Office of Migration in Brussels on Thursday, Oct. 1, 2015. European Union nations will discuss on Tuesday, May 14, 2024, sweeping new reforms to the bloc's failed asylum system as campaigning for Europe-wide elections next month gathers pace, with migration expected to be an important issue. (AP Photo/Geert Vanden Wijngaert, File)

FILE - Migrants aboard a rubber boat end up in the water while others cling on to a centifloat before being rescued by a team of the Sea Watch-3, around 35 miles away from Libya, Monday, Oct. 18, 2021. European Union nations will discuss on Tuesday, May 14, 2024, sweeping new reforms to the bloc's failed asylum system as campaigning for Europe-wide elections next month gathers pace, with migration expected to be an important issue. (AP Photo/Valeria Mongelli, File)