The golden angel once glimmered majestically from Notre Dame's vault.

Now, with a broken nose, chipped gold-leaf and a smashed bust, it stares up blankly at a warehouse roof in the outskirts of Paris where blackened fragments of the famed cathedral's stained glass mingle with organ pipes and jagged vault stones.

Scientists at the French government's Historical Monuments Research Laboratory are using these objects as clues in an urgent and vital task: Working out how to safely restore the beloved Paris cathedral and identify what perils remain inside the monument in a race against the clock.

In this photo taken on Wednesday, Oct. 9, 2019, stone expert Jean-Didier Mertz, gestures next to the remain of the golden angel that was once atop Notre Dame cathedral, in a warehouse at Champs-sur-Marne, west of Paris. Scientists at the French government's Historical Monuments Research Laboratory are using these objects as clues in an urgent and vital task, working out how to safely restore the beloved Paris cathedral and identify what perils remain inside in a race against the clock. (AP PhotoFrancois Mori)

Debris is still falling from Notre Dame's roof as fears over dust poisoning from the cathedral's burnt-out lead roof has frightened the people of Paris and a spring 2020 deadline looms for a major diagnostic report on how to fix the lab's most famous patient.

"For the moment, the cathedral is in an emergency state of peril... It's still falling, stones fall regularly," said Aline Magnien, the lab director. "Fifteen to 20 (scientists) have been working at Notre Dame, notably to filter out the rubble. Everything that fell from the roof vaults — the wood, the metal, the stone — has been the object of a sort of archaeological excavation."

The April 15 inferno has turned the lab in the sleepy town of Champs-sur-Marne into a hive of activity, with geologists, microbiologists and experts in metal and stained glass manning laser beams, microscopes and state-of-the-art computer technology to analyze key pieces of debris — work that goes on often until midnight.

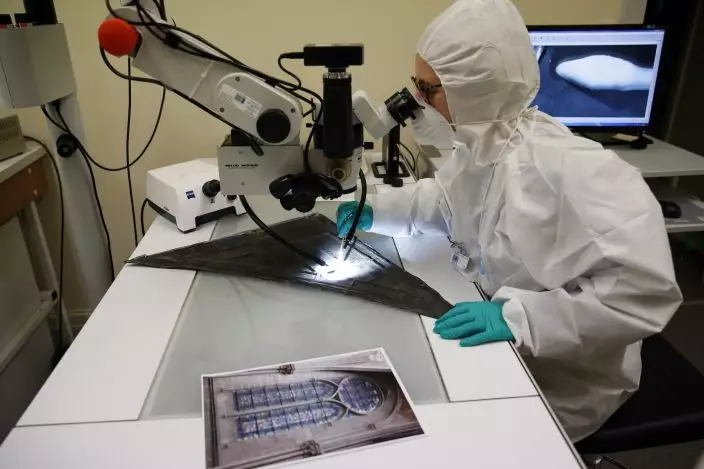

In this photo taken on Wednesday, Oct. 9, 2019, stone expert Jean-Didier Mertz shows the tests of laser cleaning technique on a broken vault stone from Notre Dame cathedral in a warehouse at Champs-sur-Marne, west of Paris. Scientists at the French government's Historical Monuments Research Laboratory are using these objects as clues in an urgent and vital task, working out how to safely restore the beloved Paris cathedral and identify what perils remain inside in a race against the clock. (AP PhotoFrancois Mori)

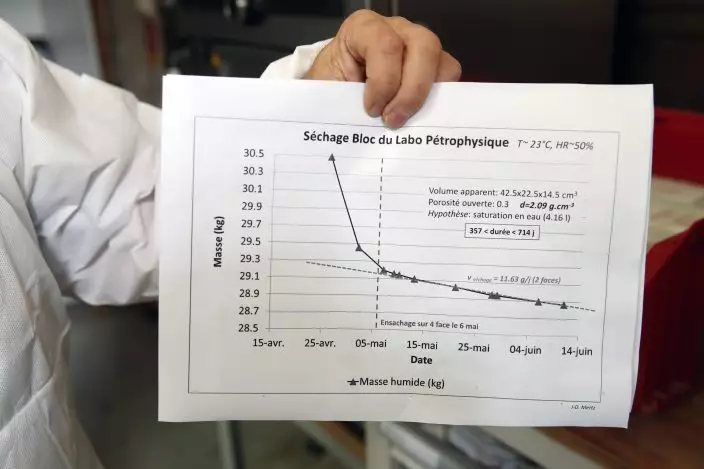

One key question the scientists are trying to establish is how damaged the remaining stone is, after being not only burnt but then doused in water from firefighters.

Architects need to know how strong the stone is to know how heavy the cathedral's new roof and spire can be — without risking further calamity.

The lab's stone expert, Jean-Didier Mertz, proudly showed off his myriad machines, glass atriums and vault stones wrapped in kitchen cling-film. He said Notre Dame's stone could have been weakened by up to 50% because of water that caused it to expand in a close-knit stone structure that has little natural breathing room.

In this photo taken on Wednesday, Oct. 9, 2019, stone expert Jean-Didier Mertz, looks on next to the remains of the golden angel that was once atop Notre Dame cathedral, in a warehouse at Champs-sur-Marne, west of Paris. Scientists at the French government's Historical Monuments Research Laboratory are using these objects as clues in an urgent and vital task, working out how to safely restore the beloved Paris cathedral and identify what perils remain inside in a race against the clock. (AP PhotoFrancois Mori)

Although Notre Dame's two medieval towers were spared from collapsing in the fire that destroyed the cathedral's roof and spire, he warned that the stone in the French Gothic masterpiece is still not out of danger.

"Since the construction and (architect) Viollet-le-Duc's revamp in 1864, the stones haven't seen a single drop of water," he explained. "The fact there was the fire and water to extinguish it totally changed the material's surface."

Even though debris is still falling down at the cathedral, Mertz said he did not think the remaining stone structure would come down.

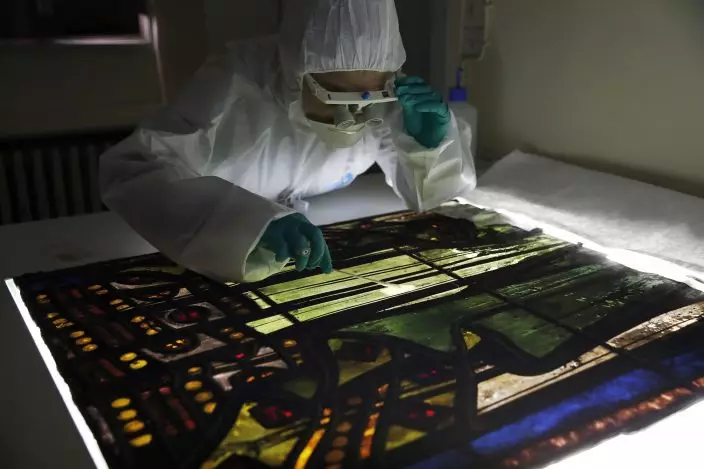

In this photo taken on Wednesday, Oct. 9, 2019, Glass specialist Claudine Loisel checks the Notre Dame cathedral's stained-glass windows in a lab at Champs-sur-Marne, west of Paris. Scientists at the French government's Historical Monuments Research Laboratory are using these objects as clues in an urgent and vital task, working out how to safely restore the beloved Paris cathedral and identify what perils remain inside in a race against the clock. (AP PhotoFrancois Mori)

"If the stone was going to collapse, it would have collapsed already. But it does need serious help," he added.

He says he will recommend using a stone-hardening liquid coating on the surface of the stones. For stones with fissures, he says a mortar mix will be used to fill the holes.

Officials at the lab currently estimate 500 cubic meters of stone will be required to rebuild parts of the church.

In this photo taken on Wednesday, Oct. 9, 2019, Glass specialist Claudine Loisel checks the Notre Dame cathedral's stained-glass windows in a lab at Champs-sur-Marne, west of Paris. Scientists at the French government's Historical Monuments Research Laboratory are using these objects as clues in an urgent and vital task, working out how to safely restore the beloved Paris cathedral and identify what perils remain inside in a race against the clock. (AP PhotoFrancois Mori)

"It's a tricky subject, because the Notre Dame quarries no longer exist... Where are we going to find them?" Magnien asked.

The lab combines high tech with a typically Gallic environment.

Located inside the Champs-sur-Marne chateau, the team of scientists wearing plastic aprons, elasticated shoe covers and respiratory masks crack jokes amid the turreted 18th-century architecture.

In this photo taken on Wednesday, Oct. 9, 2019, Glass specialist Claudine Loisel checks the Notre Dame cathedral's stained-glass windows in a lab at Champs-sur-Marne, west of Paris. Scientists at the French government's Historical Monuments Research Laboratory are using these objects as clues in an urgent and vital task, working out how to safely restore the beloved Paris cathedral and identify what perils remain inside in a race against the clock. (AP PhotoFrancois Mori)

Like the setting, their work has one foot in the future and one in the past.

Their analysis of the previously unseen historic debris has ended up revealing secrets about the cathedral and the incredible talents of the medieval architects who designed it.

A small layer of plaster found on the cathedral's fallen vault stones initially confounded the lab's experts, given that plaster is an insulating material and not a glue-like mortar that would have normally held the stones together.

In this photo taken on Wednesday, Oct. 9, 2019, stone expert Jean-Didier Mertz, displays his measure of the drying time for a stone from Notre Dame cathedral, in a lab at Champs-sur-Marne, west of Paris. Scientists at the French government's Historical Monuments Research Laboratory are using these objects as clues in an urgent and vital task, working out how to safely restore the beloved Paris cathedral and identify what perils remain inside in a race against the clock. (AP PhotoFrancois Mori)

It dawned on them that the "medieval engineers might have built in a fire safety system to slow down any potential fire," Mertz said with a beaming smile.

The scientists also complimented the skills of modern-day fire experts.

Glass specialist Claudine Loisel explained how Notre Dame's stained-glass windows were saved by the skill of the French firefighters who'd learned the lessons of 1984 blaze at York Minster in northern England. They didn't douse the windows with water, Loisel said, and only gently sprinkled the surrounding area, thus preventing the glass from exploding.

In this photo taken on Wednesday, Oct. 9, 2019, stone expert Jean-Didier Mertz displays a broken vault stone from Notre Dame cathedral in a warehouse at Champs-sur-Marne, west of Paris. Scientists at the French government's Historical Monuments Research Laboratory are using these objects as clues in an urgent and vital task, working out how to safely restore the beloved Paris cathedral and identify what perils remain inside in a race against the clock. (AP PhotoFrancois Mori)

Loisel, like others on her team, talks of Notre Dame like a doctor would of a sick patient.

"The stained-glass windows are in good shape. We have some pathologies, we might have some breakages from time to time, linked to thermal shock," she explained as she gently cleaned a window fragment from cathedral's east wing. "But in contrast to what we could have imagined, we have hardly anything."

Another key question is the cathedral's lead.

The blaze burnt up an estimated 200 tons of lead, a key material in its 19th-century roof, some of which went far into the Paris atmosphere.

After the fire, high levels of lead were recorded in the immediate neighborhood and in the blood of some local children. The massive cleanup inside the cathedral itself was briefly suspended until special protection measures for workers were put into place.

Aurelia Azema, Metals chief at the Historical Monuments Research Laboratory, said her job was to not only advise on how to clean the cathedral without damaging the original materials, but to create a lead "fingerprint" to know where lead that the fire spat out landed beyond the building's walls.

"Knowing that digital fingerprint of the cathedral, we will be able to compare it will the lead that went into the atmosphere and to know (if) the traces we have found in Paris match the lead that was in the cathedral," she said.

French President Emmanuel Macron made an ambitious pledge shortly after the catastrophe that Notre Dame would be rebuilt by 2024, enlisting 71-year-old former army chief Jean-Louis Georgelin to crack the whip. The tight timeline has prompted widespread disbelief among architects, renovation experts and others, including some of the lab's employees.

When asked about how the restorers plan to finish such an extensive restoration in just five years, the lab's deputy director shrugged his shoulders.

"We have a general for that," Magnien said with a smile.

Follow Thomas Adamson at https://twitter.com/ThomasAdamson_K