The bullet holes in the brick wall of a former post office serve as a reminder of how Appalachian coal miners fought to improve the lives of workers a century ago.

Ten people were killed in a gun battle between miners, who were led by a local police chief, and a group of private security guards hired to evict them for joining a union in Matewan, a small “company town” in West Virginia.

Plans to publicly commemorate what became known as the Matewan Massacre have been delayed by the coronavirus pandemic until September at least. But historians consider the bloodshed on May 19, 1920, memorialized in the 1987 film “Matewan,” to be a landmark moment in the battles for workers’ rights that raged across the Appalachian coalfields in the early 20th century.

In this Tuesday, May 12, 2020, is a former corner post office in Matewan, W.Va. On May 19, 1920, coal miners, led by a local police chief, and detectives hired by a coal company to evict unionizing miners from their homes were involved in a gun battle on the street. Ten people died in the Matewan Massacre. (AP PhotoJohn Raby)

“The company town system was extremely oppressive," said Lou Martin, a history professor at Chatham University in Pittsburgh and a board member of the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum in Matewan. "The company owned the houses, the only store in town, ran the church and controlled every aspect of the miners’ lives.”

Company towns were particularly prevalent in remote areas like southern West Virginia, which had the nation’s largest concentration of nonunion minors in 1920. And when the United Mine Workers came to town, coal companies retaliated.

The Stone Mountain Coal Co. hired Baldwin-Felts Agency detectives to evict union families from company-owned homes. Executive Albert Felts brought a dozen men to Matewan, including two who had been involved in violent strike-breaking efforts six years earlier in Ludlow, Colorado.

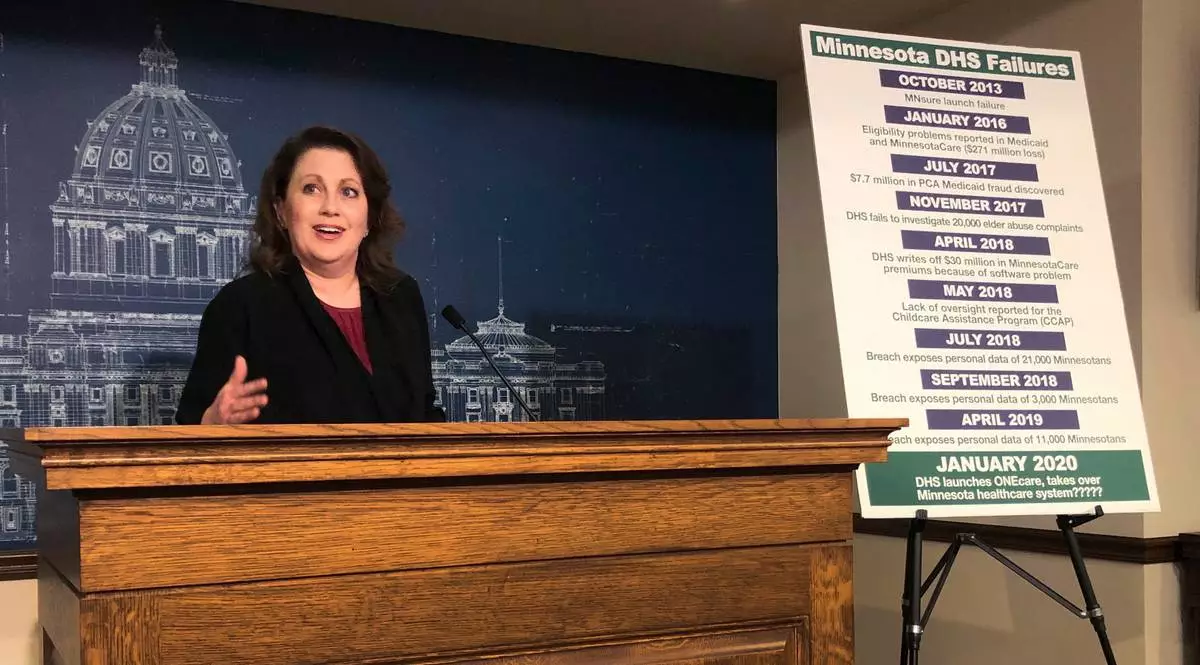

In this Tuesday, May 12, 2020, photo, West Virginia Mine Wars Museum tour guide Kim McCoy points to bullet holes still visible from a gunfight between miners and detectives hired by a coal company in Matewan, W.Va. Ten people died in the Matewan Massacre on May 19, 1920. McCoy is a great niece of Sid Hatfield, the Matewan police chief who sided with the miners and was involved in the shootings. Hatfield was shot to death a year later by coal company detectives. (AP PhotoJohn Raby)

The detectives removed the families and were headed out when they were confronted by a group led by Matewan Police Chief Sid Hatfield. Killed in the gunfire were Albert Felts, his brother, Lee, five other Baldwin-Felts detectives, Matewan Mayor Cabell Testerman and two bystanders.

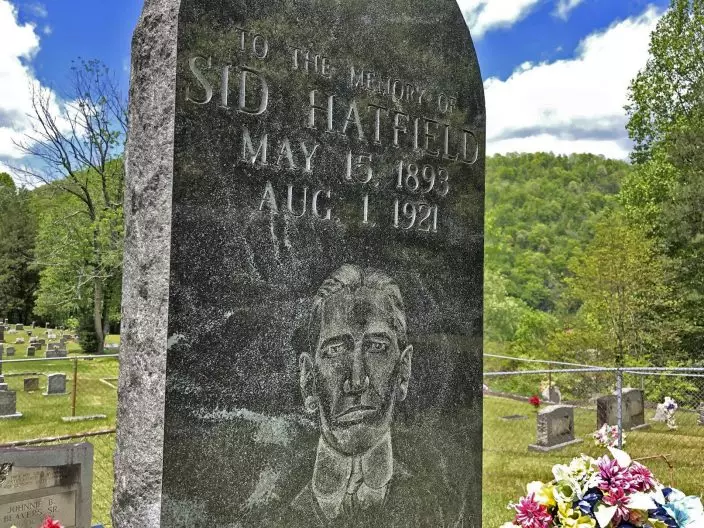

Fifteen months later, Hatfield was gone, too, gunned down by Baldwin-Felts detectives on the McDowell County courthouse steps. He was 28.

More determined than ever to organize, miners marched by the thousands, leading to the 12-day Battle of Blair Mountain in the summer of 1921. Sixteen men died before they surrendered to federal troops.

In this Tuesday, May 12, 2020, photo the town of Matewan, W.Va, is shown through a river floodwall gate. A gunfight between miners and detectives hired by a coal company on a Matewan street left 10 people dead on May 19, 1920. It became known as the Matewan Massacre. (AP PhotoJohn Raby)

The UMW's campaign in southern West Virginia then stalled, along with labor setbacks in steel, meat packing and railroads following World War I. Appalachian coal operators felt they needed to remain nonunion in order to survive, Martin said.

“They believed everything else was against them — the terrain, freight rates,” he said. “But paying lower wages, they could stay in business and remain profitable.”

But “miners would long remember the lengths that the companies went to to prevent them from having basic rights that would help them organize and get a standard of living,” Martin said.

In this Tuesday, May 12, 2020, photo is David Hatfield at the bed and breakfast he owns in Matewan, W.Va. Hatfield is a great nephew of Sid Hatfield, a Matewan police chief who was in a gun battle involving miners and coal company detectives on May 19, 1920. The Matewan Massacre left 10 people dead. (AP PhotoJohn Raby)

In her 1925 autobiography, union organizer Mary Harris “Mother" Jones said she witnessed multiple conflicts between “the industrial slaves and their masters” during visits to West Virginia.

State officials were reluctant to challenge the coal operators.

“There is never peace in West Virginia because there is never justice,” Jones wrote. “'Medieval West Virginia!' With its tent colonies on the bleak hills! With its grim men and women! When I get to the other side, I shall tell God Almighty about West Virginia!”

In this Tuesday, May 12, 2020, photo is the gravestone of Sid Hatfield, in Buskirk, Ky. Hatfield was the police chief in nearby Matewan, W.Va He was involved in a gunfight between miners and detectives hired by a coal company. Hatfield survived the May 19, 1920, gunfight that left 10 people dead but he was fatally shot a year later. (AP PhotoJohn Raby)

When workers were finally guaranteed the right to collectively bargain in 1933 as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal, West Virginia coal miners joined the UMW in droves, Martin said.

The UMW also bankrolled the organization that would become the United Steelworkers, and with John L. Lewis leading the UMW from 1920 to 1960, national membership peaked at about 500,000 during World War II.

The union helped push through major improvements to health, safety and pensions, across the U.S. workforce. But over the next half century, mechanization, fierce industry opposition and the rise of competing fuel sources severely reduced coal jobs and union membership.

In this Tuesday, May 12, 2020, photo is a floodwall protecting the town of Matewan, W.Va, from the Tug Fork of the Big Sandy River. (AP PhotoJohn Raby)

The Stone Mountain Coal Co. is long gone, but Matewan still stands, as does its union hall. The town has lost half of its population since 1980, but it has survived the shootings, three dozen floods from the Tug Fork of the Big Sandy River before a floodwall was built, a 1992 fire that destroyed several downtown businesses and the opioid crisis that has ravaged the state.

Feelings about unions are mixed, but locals say the movie helped lift a shroud of silence that kept people from even mentioning the shootings. Resident Wilma Steele, whose husband is a retired union miner, said she didn't read about the battles of Matewan and Blair Mountain until she went to college.

Now the Kentucky border town of about 430 residents leans on tourism about the massacre, as well as the famous feud between the Hatfields of West Virginia and the McCoys of Kentucky. A vast network of ATV trails draws also draws recreational tourists.

In this Tuesday, May 12, 2020, photo is a mural depicting miners working in coal mines in Matewan, W.Va. On May 19, 1920, a group of miners, who were led by a local police chief, and detectives hired by a coal company to evict unionizing miners from their homes were involved in a gun battle on the street. Ten people died in the Matewan Massacre. (AP PhotoJohn Raby)

Museum tour guide Kim McCoy, whose maiden name is Hatfield, married a great-grandson of the McCoy family. She grew up in Matewan's coal camps and is a great niece both of family patriarch William Anderson “Devil Anse” Hatfield and Sid Hatfield, who resisted when hired guns evicted his neighbors a century ago.

“The Hatfield name is very distinctive in our area,” McCoy said. “Sid being part of the Matewan Massacre and really standing up for the miners and the miners' basic human rights, there's a lot of honor in that.”

David Hatfield, who operates a Matewan bed-and-breakfast and is Sid Hatfield's great nephew, said Americans today benefit from what the miners strived for, including better working conditions.

"It's important to me because my family helped bring that about in some part," he said.

Online:

http://www.historicmatewan.com