Doctors Without Borders said it closed its operation on Tuesday in Kabul, ending yearslong work to support a maternity hospital in the Afghan capital. The closure came a month after a horrific attack at the facility killed 24 people, including two infants, nurses and several young mothers.

The international charity, also known by its French acronym MSF, said it would keep its other programs in Afghanistan running, but did not go into details.

The May 12 attack at the maternity hospital set off an hours-long shootout with Afghan police and also left more than a dozen people wounded. The hospital in Dashti Barchi, a mostly Shiite neighborhood, was the Geneva-based group's only project in the Afghan capital.

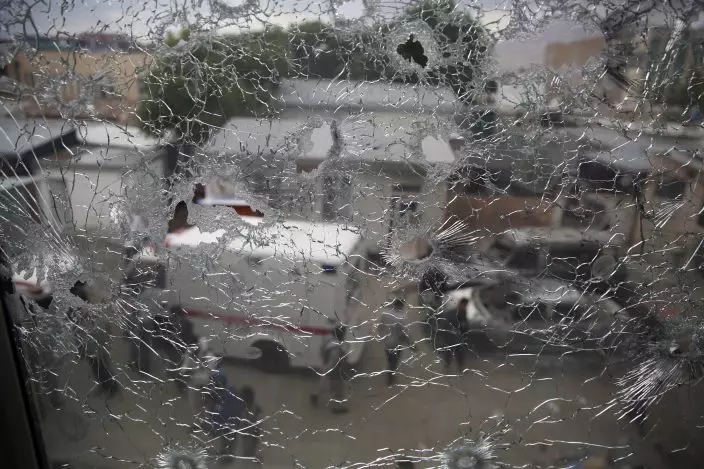

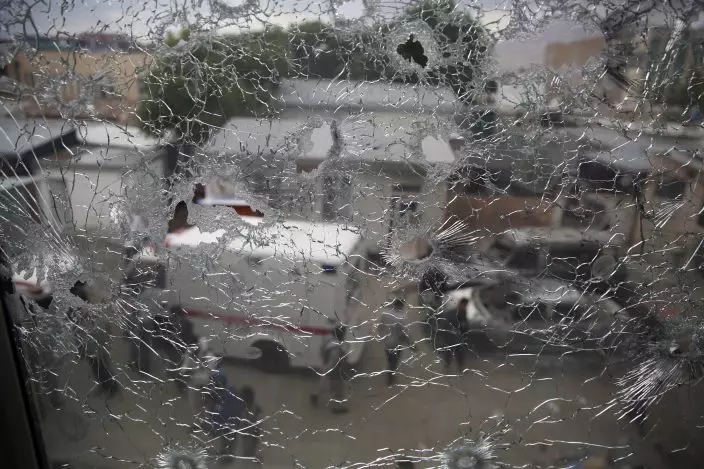

FILE-in this Tuesday, May 12, 2020, photo, security officers are seen through the shattered window of a maternity hospital after gunmen attacked, in Kabul, Afghanistan, The Geneva-based international health organization Medicins Sans Frontieres MSF– also known as Doctors Without Borders Tuesday closed its operations in the Afghan capital Kabul after a horrific attack on its maternity hospital in May. (AP PhotoRahmat Gul, File)

No one claimed responsibility for the assault. The Taliban promptly denied involvement in the attack, which the U.S. said bore all the hallmarks of the Islamic State group's affiliate in Afghanistan — an attack targeting the country’s minority Shiites in a neighborhood of Kabul that IS militants have repeatedly attacked in the past.

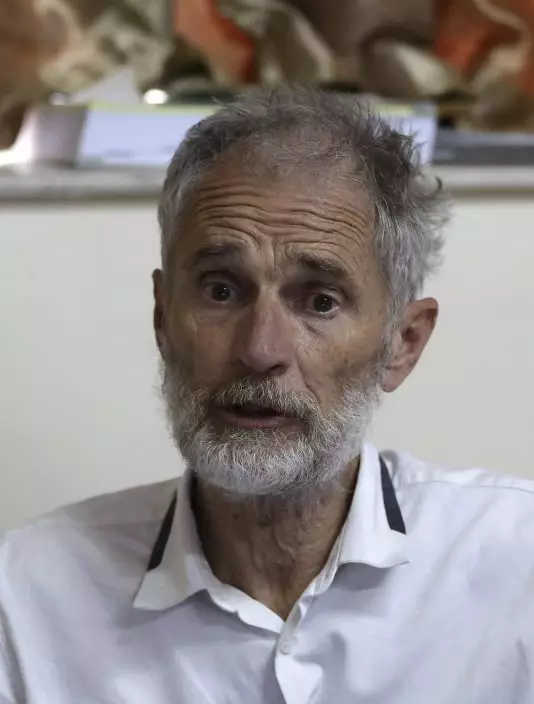

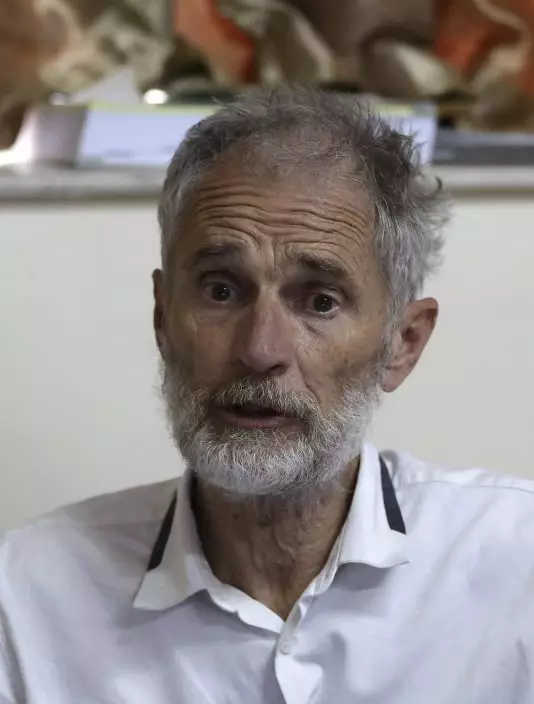

“This was not an easy decision,” said Brian Moller, the MSF head of programs for Afghanistan. “We don’t know who is responsible for this attack, we don’t know the rationale or intent behind the attack and we don’t know who was actively targeted, whether it was foreigners, whether it was MSF, whether it was the Hazara community or the Shiite community at large. “

Moller said the organization still hopes that an Afghan government investigation would uncover who was behind it.

Brian Moller, MSF, Medicins Sans Frontieres, head of programs of Afghanistan, speaks during an interview to the Associated press in Kabul, Afghanistan, Tuesday, June 16, 2020. The Geneva-based international health organization Medicins Sans Frontieres MSF– also known as Doctors Without Borders Tuesday closed its operations in the Afghan capital Kabul after a horrific attack on its maternity hospital in May. (AP PhotoRahmat Gul)

"So, given this lack of information ... we have decided that it is a safer option to close this project for the time being,” Moller told The Associated Press.

MSF had been working at the clinic in the predominantly Hazara neighborhood in collaboration with the Afghan Ministry of Public Health since 2014, providing free-of-charge maternity and neonatal care. The group started working in Afghanistan in 1980 and continues to run medical programs in the provinces of Helmand, Herat, Kandahar, Khost, and Kunduz. Other projects would continue, MSF said.

“It is going to affect a lot of people, not just our team, but also the wider community at large, in particular the community that we were serving in Dasht-e-Barchi," Moller said .

FILE-in this Tuesday, May 12, 2020, photo, a security officer carries a baby after gunmen attacked a maternity hospital, in Kabul, Afghanistan. The Geneva-based international health organization Medicins Sans Frontieres MSF– also known as Doctors Without Borders Tuesday closed its operations in the Afghan capital Kabul after a horrific attack on its maternity hospital in May. (AP PhotoRahmat Gul, File)

The work that the organization did at the clinic affected some 1.5 million people of the area, he added. Last year, 16,000 babies were delivered at the hospital, a statistic that MSF was proud of. Now, around 130 hospital staff members funded by MSF would lose their pay.

“It is a huge impact, not just for our organization, but for the community at large,” Moller added.

The May attack in Kabul was not the worst involving MSF. In October 2015, a U.S. Air Force AC-130 gunship repeatedly struck a well-marked Doctors Without Borders hospital, killing 30 people in the northern Afghan city of Kunduz.

At the time, U.S. and Afghan forces were locked in a ground battle to retake the city of 300,000 from the Taliban. There were 105 patients, 140 Afghan staffers and nine international staff inside, along with dozens of visitors who were caring for friends and relatives as is a custom in Afghanistan.

Associated Press writer Tameem Akhgar in Kabul, Afghanistan, contributed to this report.

KABUL, Afghanistan (AP) — For 10 hours a day, Rahimullah sells socks from his cart in eastern Kabul, earning about $4.5 to $6 per day. It's a pittance, but it’s all he has to feed his family of five.

Rahimullah, who like many Afghans goes by only one name, is one of millions of Afghans who rely on humanitarian aid, both from the Afghan authorities and from international charity organizations, for survival. An estimated 22.9 million people — nearly half the population — required aid in 2025, the International Committee for the Red Cross said in an article on its website Monday.

But severe cuts in international aid — including the halting of U.S. aid to programs such as food distribution run by the United Nations’ World Food Program — have severed this lifeline.

More than 17 million people in Afghanistan now face crisis levels of hunger in the winter, the World Food Program warned last week, 3 million more than were at risk more than a year ago.

The slashing in aid has come as Afghanistan is battered by a struggling economy, recurrent droughts, two deadly earthquakes and the mass influx of Afghan refugees expelled from countries such as Iran and Pakistan. The resulting multiple shocks have severely pressured resources, including of housing and food.

Tom Fletcher, the U.N. humanitarian chief, told the Security Council in mid-December that the situation was compounded by “overlapping shocks,” including the recent earthquakes and increasing restrictions on humanitarian aid access and staff.

While Fletcher said nearly 22 million Afghans will need U.N. assistance in 2026, his organization will focus on 3.9 million facing the most urgent need of lifesaving help due to reduced donor contributions.

Fletcher said this winter was “the first in years with almost no international food distribution.”

“As a result, only about 1 million of the most vulnerable people have received food assistance during the lean season in 2025,” compared to 5.6 million last year, he said.

The year has been devastating for U.N. humanitarian organizations, which have had to cut thousands of jobs and spending in the wake of aid cuts.

“We are grateful to all of you who have continued to support Afghanistan. But as we look towards 2026, we risk a further contraction of life-saving help — at a time when food insecurity, health needs, strain on basic services, and protection risks are all rising,” Fletcher said.

The return of millions of refugees has added pressure on an already teetering system. Minister of Refugees and Repatriation Affairs Abdul Kabir said Sunday that 7.1 million Afghan refugees had returned to the country over the last four years, according to a statement on the ministry website.

Rahimullah, 29, was one of them. The former Afghan Army soldier fled to neighboring Pakistan after the Taliban seized power in 2021. He was deported back to Afghanistan two years later, and initially received aid in the form of cash as well as food.

“The assistance was helping me a lot,” he said. But without it, “now I don’t have enough money to live on. God forbid, if I were to face a serious illness or any other problem, it would be very difficult for me to handle because I don’t have any extra money for expenses.”

The massive influx of former refugees has also sent rents skyrocketing. Rahimullah’s landlord has nearly doubled the rent of his tiny two-room home, with walls made half of concrete and half of mud and a homemade mud stove for cooking. Instead of 4,500 afghanis (about $67), he now wants 8,000 afghanis (about $120) – a sum Rahimullah cannot afford. So he, his wife, daughter and two young sons will have to move next month. They don’t know where to.

Before the Taliban takeover, Rahimullah had a decent salary and his wife worked as a teacher. But the new government’s draconian restrictions on women and girls mean women are barred from nearly all jobs, and his wife is unemployed.

“Now the situation is such that even if we find money for flour, we don’t have it for oil, and even if we find it for oil, we can’t pay the rent. And then there is the extra electricity bill,” Rahimullah said.

In Afghanistan’s northern province of Badakhshan, Sherin Gul is desperate. In 2023, her family of 12 got supplies of flour, oil, rice, beans, pulses, salt and biscuits. It was a lifesaver.

But it only lasted six months. Now, there is nothing. Her husband is old and weak and cannot work, she said. With 10 children, seven girls and three boys between the ages of 7 and 27, the burden of providing for the family has fallen on her 23-year-old son – the only one old enough to work. But even he only finds occasional jobs.

“There are 12 of us … and one person working cannot cover the expenses,” she said. “We are in great trouble.”

Sometimes neighbors take pity on them and give them food. Often, they all go hungry.

“There have been times when we have nothing to eat at night, and my little children have fallen asleep without food,” Gul said. “I have only given them green tea and they have fallen asleep crying.”

Before the Taliban takeover, Gul worked as a cleaner, earning just about enough to feed her family. But the ban on women working has left her unemployed, and she said she developed a nervous disorder and is often sick.

Compounding their misery is the harsh cold of the northern Afghan winter, when snow halts construction work where her son can sometimes find jobs. And there is the added expense of firewood and charcoal.

“If this situation continues like this, we may face severe hunger,” Gul said. “And then it will be very difficult for us to survive in this cold weather.”

Associated Press writers Farnoush Amiri at the United Nations, Jamey Keaten in Geneva and Elena Becatoros in Athens contributed to this report.

FILE - The body of a girl is placed on a bed frame after being pulled from the rubble following Sunday night's powerful 6.0-magnitude earthquake, in a remote area of Kunar province, Afghanistan, Tuesday, Sept. 2, 2025, (AP Photo/Nava Jamshidi, File)

FILE - A boy injured during Sunday's powerful 6.0-magnitude earthquake that struck eastern Afghanistan lies in a hospital bed in Jalalabad, Afghanistan, Tuesday, Sept. 2, 2025. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - A woman and her children, survivors of Sunday night's 6.0-magnitude earthquake, wait for assistance in the village of Wadir, Kunar province, eastern Afghanistan, Tuesday, Sept. 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Nava Jamshidi, File)

FILE - An Afghan boy injured in a powerful earthquake that struck eastern Afghanistan on Sunday receives treatment at Nangarhar Regional Hospital in Jalalabad, Afghanistan, Wednesday, Sept. 3, 2025. (AP Photo/Siddiqullah Alizai, File)

FILE - Afghan refugee families heading back to their homeland, gather next to trucks loaded with their belongings as they wait for documentation at the UNHCR Voluntary Repatriation Centre in Azakhel, Nowshera a district of Pakistan's Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Monday, Aug. 25, 2025. (AP Photo/Muhammad Sajjad, File)