A friendly feast shared by the plucky Pilgrims and their native neighbors? That’s yesterday’s Thanksgiving story.

Students in many U.S. schools are now learning a more complex lesson that includes conflict, injustice and a new focus on the people who lived on the land for hundreds of years before European settlers arrived and named it New England.

Click to Gallery

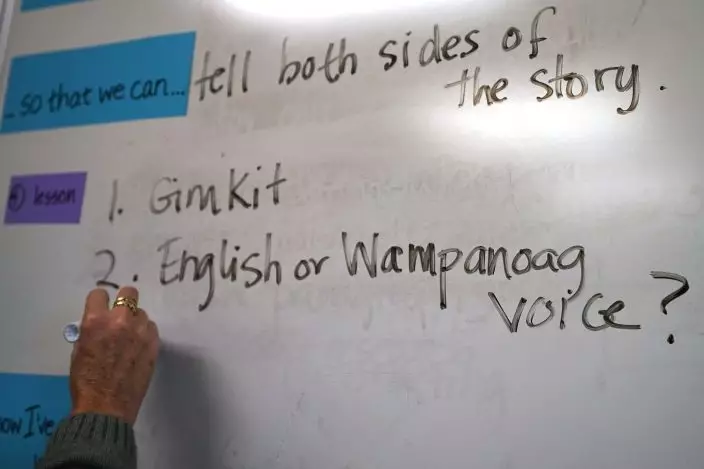

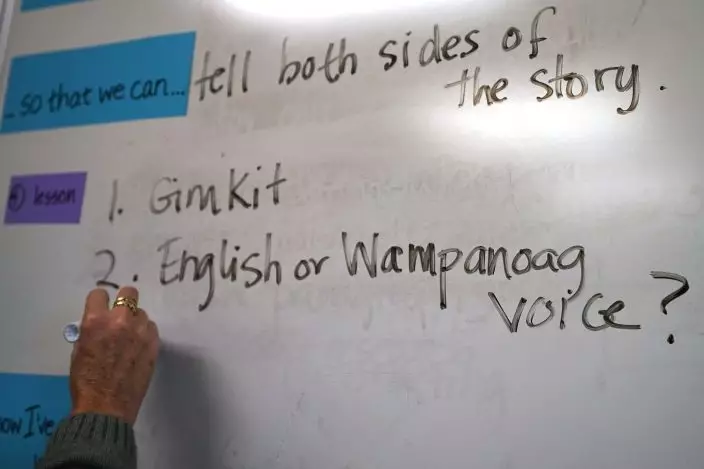

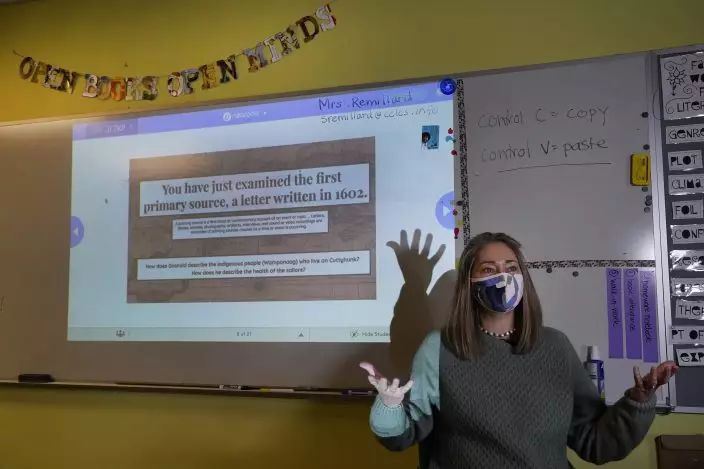

Susannah Remillard writes on the board for her sixth-grade class at Cape Cod Lighthouse Charter School, Thursday, Nov. 19, 2020, in East Harwich, Mass. In a growing number of U.S. schools, students are now learning a more complex Thanksgiving story that involves conflict, injustice and a new focus on the native people who lived in New England for hundreds of years before European settlers arrived. (AP PhotoElise Amendola)

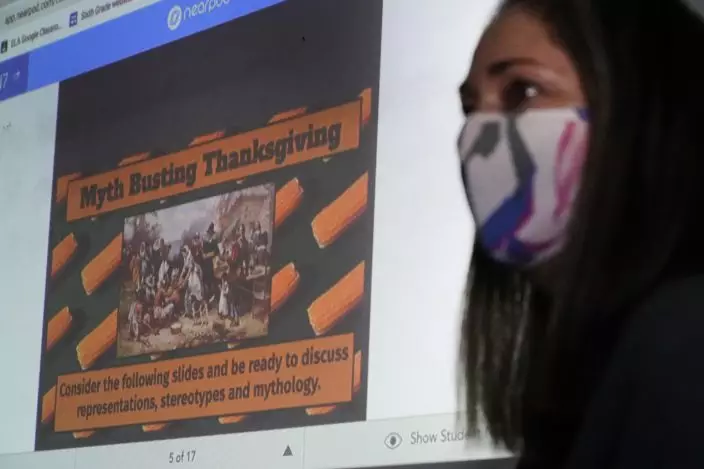

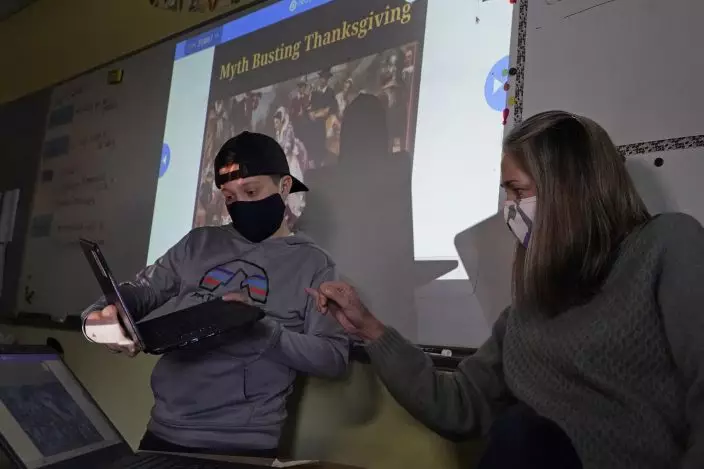

Susannah Remillard teaches her sixth-grade students at Cape Cod Lighthouse Charter School, Thursday, Nov. 19, 2020, in East Harwich, Mass. In a growing number of U.S. schools, students are now learning a more complex Thanksgiving story that involves conflict, injustice and a new focus on the native people who lived in New England for centuries before European settlers arrived. (AP PhotoElise Amendola)

FILE - In this Sept. 25, 2020, file photo, Annawon Weeden sits for a portrait outside his home in Oakdale, Conn. As schools rethink Thanksgiving lessons, many are also looking to expand lessons on native cultures throughout the year. And while schools are increasingly turning to lessons created by native educators, some are also working to bring native voices directly into the classroom. A growing number of schools around Boston have started hosting annual visits from Weeden, a performing artist and member of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe. (AP PhotoDavid Goldman, File)

A sixth-grade student in Susannah Remillard's classroom works on her laptop at Cape Cod Lighthouse Charter School, Thursday, Nov. 19, 2020, in East Harwich, Mass. In a growing number of U.S. schools, students are now learning a more complex Thanksgiving story that involves conflict, injustice and a new focus on the native people who lived in New England for hundreds of years before European settlers arrived. (AP PhotoElise Amendola)

Sixth-grade students listen to instruction in Susannah Remillard's class at Cape Cod Lighthouse Charter School, Thursday, Nov. 19, 2020, in East Harwich, Mass. In a growing number of U.S. schools, students are now learning a more complex Thanksgiving story that involves conflict, injustice and a new focus on the native people who lived in New England for hundreds of years before European settlers arrived. (AP PhotoElise Amendola)

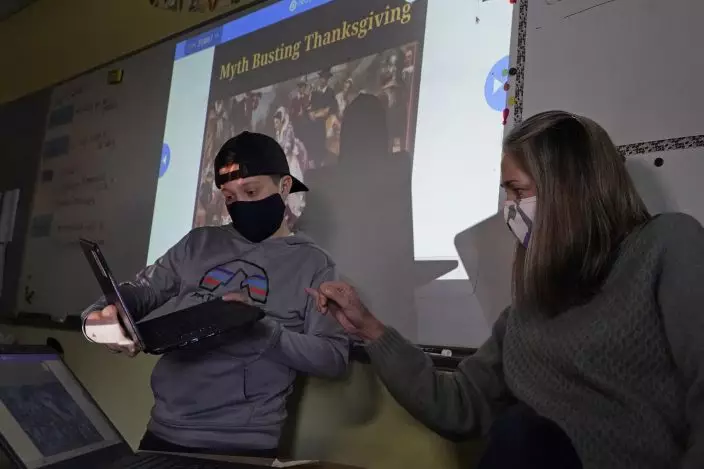

Susannah Remillard, right, works with one of her sixth-grade students at Cape Cod Lighthouse Charter School, Thursday, Nov. 19, 2020, in East Harwich, Mass. In a growing number of U.S. schools, students are now learning a more complex Thanksgiving story that involves conflict, injustice and a new focus on the native people who lived in New England for hundreds of years before European settlers arrived. (AP PhotoElise Amendola)

Susannah Remillard, background standing, walks among her sixth-grade students at Cape Cod Lighthouse Charter School, Thursday, Nov. 19, 2020, in East Harwich, Mass. In a growing number of U.S. schools, students are now learning a more complex Thanksgiving story that involves conflict, injustice and a new focus on the native people who lived in New England for hundreds of years before European settlers arrived. (AP PhotoElise Amendola)

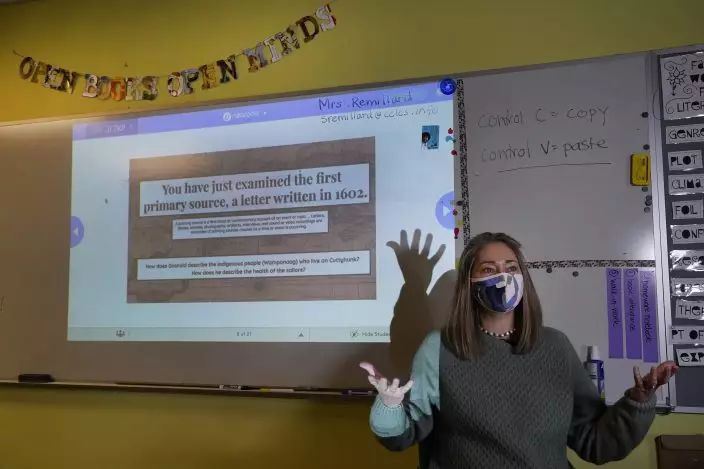

Susannah Remillard speaks in her sixth-grade classroom at Cape Cod Lighthouse Charter School, Thursday, Nov. 19, 2020, in East Harwich, Mass. In a growing number of U.S. schools, students are now learning a more complex Thanksgiving story that involves conflict, injustice and a new focus on the native people who lived in New England for hundreds of years before European settlers arrived. (AP PhotoElise Amendola)

Inspired by the nation’s reckoning with systemic racism, schools are scrapping and rewriting lessons that treated Native Americans as a footnote in a story about white settlers. Instead of making Pilgrim hats, students are hearing what scholars call “hard history” — the more shameful aspects of the past.

Susannah Remillard writes on the board for her sixth-grade class at Cape Cod Lighthouse Charter School, Thursday, Nov. 19, 2020, in East Harwich, Mass. In a growing number of U.S. schools, students are now learning a more complex Thanksgiving story that involves conflict, injustice and a new focus on the native people who lived in New England for hundreds of years before European settlers arrived. (AP PhotoElise Amendola)

Students still learn about the 1621 feast, but many are also learning that peace between the Pilgrims and Native Americans was always uneasy and later splintered into years of conflict.

On Cape Cod, language arts teacher Susannah Remillard long found that her sixth grade students had been taught far more about the Pilgrims than the Wampanoag people, the Native Americans who attended the feast. Now she's trying to balance the narrative.

She asks students to rewrite the Thanksgiving story using historical records, and then she asks them to write a poem from the perspective of a person from that time, half settlers and half Wampanoag.

Susannah Remillard teaches her sixth-grade students at Cape Cod Lighthouse Charter School, Thursday, Nov. 19, 2020, in East Harwich, Mass. In a growing number of U.S. schools, students are now learning a more complex Thanksgiving story that involves conflict, injustice and a new focus on the native people who lived in New England for centuries before European settlers arrived. (AP PhotoElise Amendola)

“We carry this Colonial view of how we teach, and now we have a moment to step outside that and think about whether that is harmful for kids, and if there isn’t a better way,” said Remillard, who teaches at Cape Cod Lighthouse Charter School in East Harwich, Massachusetts. “I think we are at a point where people are now ready to listen.”

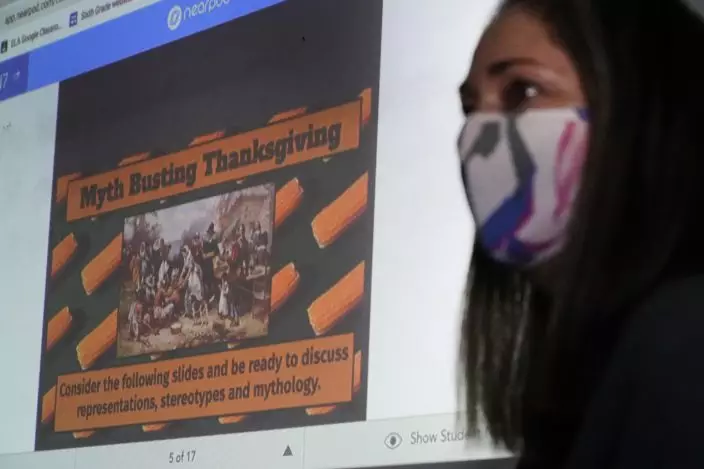

In Arlington Public Schools near Boston, students until recently dressed annually in Colonial attire. Now taboo, the costumes were abolished in 2018, and the district is working to expand and correct classroom teachings on Native Americans, including debunking Thanksgiving myths.

Students as young as kindergarten are now being taught that harvest feasts have been part of Wampanoag life since long before 1621, and that thanksgiving is a daily part of life for many tribes.

FILE - In this Sept. 25, 2020, file photo, Annawon Weeden sits for a portrait outside his home in Oakdale, Conn. As schools rethink Thanksgiving lessons, many are also looking to expand lessons on native cultures throughout the year. And while schools are increasingly turning to lessons created by native educators, some are also working to bring native voices directly into the classroom. A growing number of schools around Boston have started hosting annual visits from Weeden, a performing artist and member of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe. (AP PhotoDavid Goldman, File)

They're also being taught that the Pilgrims and Wampanoag were not friends, and that it's important to “unlearn” false notions around the feast.

“We don’t want the coloring books of the Pilgrims and the Native Americans,” said Crystal Power, a social studies coach. “We want students to engage with what really happened, with who lived here first, and to understand that there was no such thing as the New World. It was only new from one side’s perspective.”

Advocates for Indigenous education caution there's still much to improve. Change has been slow and spotty, they say, and many schools cling to insensitive traditions, including costumed dramas and paper headdresses.

A sixth-grade student in Susannah Remillard's classroom works on her laptop at Cape Cod Lighthouse Charter School, Thursday, Nov. 19, 2020, in East Harwich, Mass. In a growing number of U.S. schools, students are now learning a more complex Thanksgiving story that involves conflict, injustice and a new focus on the native people who lived in New England for hundreds of years before European settlers arrived. (AP PhotoElise Amendola)

“Progress seems to be gaining momentum, but there’s still a lot of work to do,” said Ed Schupman, manager of Native Knowledge 360, the national education initiative at the National Museum of the American Indian, and a citizen of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation of Oklahoma. “Change is still needed, and it has only been significant in some places.”

Schupman and the museum have worked with states as they create new teaching standards on Indigenous cultures. Montana in 1999 was among the first to require schools to teach tribal histories and is now joined by Washington, Oregon and others.

Even in states where it isn't mandatory, however, classrooms are becoming more inclusive.

Sixth-grade students listen to instruction in Susannah Remillard's class at Cape Cod Lighthouse Charter School, Thursday, Nov. 19, 2020, in East Harwich, Mass. In a growing number of U.S. schools, students are now learning a more complex Thanksgiving story that involves conflict, injustice and a new focus on the native people who lived in New England for hundreds of years before European settlers arrived. (AP PhotoElise Amendola)

After national protests over killings of Black people by police, Arlington's history department created a committee to examine race, which led to discussions about expanding and correcting teachings about African Americans, Native Americans and other groups too often left out.

In recent guidance, the nearby Brookline school district urged teachers to incorporate native perspectives even on topics not necessarily specific to Indigenous people. It encourages lessons, for example, on the coronavirus' impact on Native Americans, and on Neilson Powless, who recently became the first Native American in the Tour de France.

Although schools say parents have mostly embraced the changes, they acknowledge it can be polarizing. Prominent lawmakers have resisted efforts to rethink Thanksgiving, including Sen. Tom Cotton of Arkansas, a Republican who last week blasted “revisionist charlatans of the radical left."

Susannah Remillard, right, works with one of her sixth-grade students at Cape Cod Lighthouse Charter School, Thursday, Nov. 19, 2020, in East Harwich, Mass. In a growing number of U.S. schools, students are now learning a more complex Thanksgiving story that involves conflict, injustice and a new focus on the native people who lived in New England for hundreds of years before European settlers arrived. (AP PhotoElise Amendola)

“Too many may have lost the civilizational self-confidence needed to celebrate the Pilgrims,” Cotton said.

School officials say they aren't changing history, but adding parts that have been left out. Standard social studies textbooks have included little about Native Americans, and alternatives were long elusive. Teachers say that's changing, thanks to native scholars who have authored children's books, lesson plans and other materials.

In Massachusetts this year, every public school is getting copies of a new state history book co-written by a Wampanoag author and historian. The book was published to coincide with the 400th anniversary of the Mayflower’s arrival, but it notably begins thousands of years earlier, with the history of the Wampanoag people.

Susannah Remillard, background standing, walks among her sixth-grade students at Cape Cod Lighthouse Charter School, Thursday, Nov. 19, 2020, in East Harwich, Mass. In a growing number of U.S. schools, students are now learning a more complex Thanksgiving story that involves conflict, injustice and a new focus on the native people who lived in New England for hundreds of years before European settlers arrived. (AP PhotoElise Amendola)

Many schools are also adding lessons on native cultures through the year, including around Columbus Day, which some districts now mark as Indigenous Peoples Day. More are also looking for ways to bring Indigenous voices directly into the classroom.

Before the pandemic, schools around Boston hosted annual visits from Annawon Weeden, a performing artist and member of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe.

Weeden makes a point of arriving in modern clothes to dispel faulty notions about Indigenous people. Only after taking questions and debunking myths does he change into traditional regalia and demonstrate tribal dances.

Susannah Remillard speaks in her sixth-grade classroom at Cape Cod Lighthouse Charter School, Thursday, Nov. 19, 2020, in East Harwich, Mass. In a growing number of U.S. schools, students are now learning a more complex Thanksgiving story that involves conflict, injustice and a new focus on the native people who lived in New England for hundreds of years before European settlers arrived. (AP PhotoElise Amendola)

“A lot of the kids think we’re only in the past. A lot of the kids think we live in a longhouse or a teepee or whatever,” Weeden said. “Stereotypes like those are very hard to defeat.”

NUUK, Greenland (AP) — Troops from several European countries continued to arrive in Greenland on Thursday in a show of support for Denmark as talks between representatives of Denmark, Greenland and the U.S. highlighted “fundamental disagreement” over the future of the Arctic island.

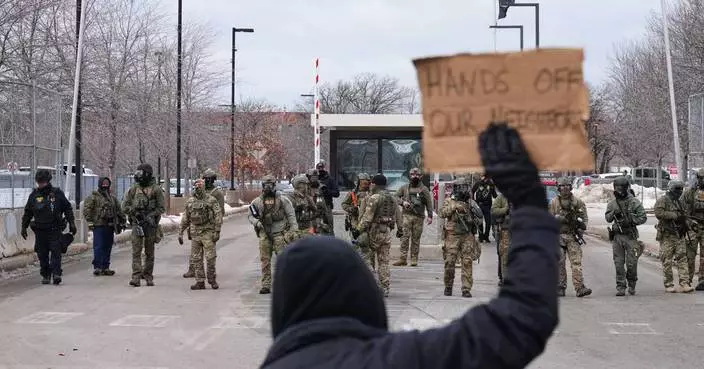

Denmark announced it would increase its military presence in Greenland on Wednesday as foreign ministers from Denmark and Greenland were preparing to meet with White House representatives in Washington. Several European partners — including France, Germany, the U.K., Norway, Sweden and the Netherlands — started sending symbolic numbers of troops already on Wednesday or promised to do so in the following days.

The troop movements were intended to portray unity among Europeans and send a signal to President Donald Trump that an American takeover of Greenland is not necessary as NATO together can safeguard the security of the Arctic region amid rising Russian and Chinese interest.

“The first French military elements are already en route” and “others will follow,” French President Emmanuel Macron announced Wednesday, as French authorities said about 15 soldiers from the mountain infantry unit were already in Nuuk for a military exercise.

Germany will deploy a reconnaissance team of 13 personnel to Greenland on Thursday, the Defense Ministry said.

On Thursday, Danish Defense Minister Troels Lund Poulsen said the intention was “to establish a more permanent military presence with a larger Danish contribution,” according to Danish broadcaster DR. He said soldiers from several NATO countries will be in Greenland on a rotation system.

Danish Foreign Minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen, flanked by his Greenlandic counterpart Vivian Motzfeldt, said Wednesday that a “fundamental disagreement” over Greenland remains with Trump after they held highly anticipated talks at the White House with Vice President JD Vance and Secretary of State Marco Rubio.

Rasmussen added that it remains “clear that the president has this wish of conquering over Greenland” but that dialogue with the U.S. would continue at a high level over the following weeks.

Inhabitants of Greenland and Denmark reacted with anxiety but also some relief that negotiations with the U.S. would go on and European support was becoming visible.

Greenland's Prime Minister Jens-Frederik Nielsen welcomed the continuation of “dialogue and diplomacy.”

“Greenland is not for sale,” he said Thursday. “Greenland does not want to be owned by the United States. Greenland does not want to be governed from the United States. Greenland does not want to be part of the United States.”

In Greenland’s capital, Nuuk, local residents told The Associated Press they were glad the first meeting between Greenlandic, Danish and American officials had taken place but suggested it left more questions than answers.

Several people said they viewed Denmark’s decision to send more troops, and promises of support from other NATO allies, as protection against possible U.S. military action. But European military officials have not suggested the goal is to deter a U.S. move against the island.

Maya Martinsen, 21, said it was “comforting to know that the Nordic countries are sending reinforcements” because Greenland is a part of Denmark and NATO.

The dispute, she said, is not about “national security” but rather about “the oils and minerals that we have that are untouched.”

On Wednesday, Poulsen announced a stepped-up military presence in the Arctic “in close cooperation with our allies,” calling it a necessity in a security environment in which “no one can predict what will happen tomorrow.”

“This means that from today and in the coming time there will be an increased military presence in and around Greenland of aircraft, ships and soldiers, including from other NATO allies,” Poulsen said.

Asked whether the European troop movements were coordinated with NATO or what role the U.S.-led military alliance might play in the exercises, NATO referred all questions to the Danish authorities. However, NATO is currently studying ways to bolster security in the Arctic.

The Russian embassy in Brussels on Thursday lambasted what it called the West's “bellicose plans” in response to “phantom threats that they generate themselves”. It said the planned military actions were part of an “anti-Russian and anti-Chinese agenda” by NATO.

“Russia has consistently maintained that the Arctic should remain a territory of peace, dialogue and equal cooperation," the embassy said.

Rasmussen announced the creation of a working group with the Americans to discuss ways to work through differences.

“The group, in our view, should focus on how to address the American security concerns, while at the same time respecting the red lines of the Kingdom of Denmark,” he said.

Commenting on the outcome of the Washington meeting on Thursday, Poulsen said the working group was “better than no working group” and “a step in the right direction.” He added nevertheless that the dialogue with the U.S. did not mean “the danger has passed.”

Speaking on Thursday, Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen said the American ambition to take over Greenland remains intact despite the Washington meeting, but she welcomed the creation of the working group.

The most important thing for Greenlanders is that they were directly represented at the meeting in the White House and that “the diplomatic dialogue has begun now,” Juno Berthelsen, a lawmaker for the pro-independence Naleraq opposition party, told AP.

A relationship with the U.S. is beneficial for Greenlanders and Americans and is “vital to the security and stability of the Arctic and the Western Alliance,” Berthelsen said. He suggested the U.S. could be involved in the creation of a coastguard for Greenland, providing funding and creating jobs for local people who can help to patrol the Arctic.

Line McGee, 38, from Copenhagen, told AP that she was glad to see some diplomatic progress. “I don’t think the threat has gone away,” she said. “But I feel slightly better than I did yesterday.”

Trump, in his Oval Office meeting with reporters, said: “We’ll see how it all works out. I think something will work out.”

Niemann reported from Copenhagen, Denmark, and Ciobanu from Warsaw, Poland.

Denmark's Foreign Minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen and Greenland's Foreign Minister Vivian Motzfeldt speak at a news conference at the Embassy of Denmark, Wednesday, Jan. 14, 2026, in Washington. (AP Photo/John McDonnell)

People walk on a street in Nuuk, Greenland, Wednesday, Jan. 14, 2026. (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka)

From center to right, Greenland Foreign Minister Vivian Motzfeldt, Denmark's Ambassador Jesper Møller Sørensen, rear, and Danish Foreign Minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen, right, arrive on Capitol Hill to meet with senators from the Arctic Caucus, in Washington, Wednesday, Jan. 14, 2026. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

An Airbus A400M transport aircraft of the German Air Force taxis over the grounds at Wunstorf Air Base in the Hanover region, Germany, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026 as troops from NATO countries, including France and Germany, are arriving in Greenland to boost security. (Moritz Frankenberg/dpa via AP)

Fishermen load fishing lines into a boat in the harbor of Nuuk, Greenland, Wednesday, Jan. 14, 2026. (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka)

Greenland Foreign Minister Vivian Motzfeldt, left, and Danish Foreign Minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen, arrive on Capitol Hill to meet with members of the Senate Arctic Caucus, in Washington, Wednesday, Jan. 14, 2026. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)