NEW YORK (AP) — Donald Trump squirmed and scowled, shook his head and muttered as Stormy Daniels described the unexpected sex she says they had nearly two decades ago, saying she remembered “trying to think of anything other than what was happening.”

It was a story Daniels has told before. This time, Trump had no choice but to sit and listen.

Click to Gallery

In this courtroom sketch, defense attorney Susan Necheles, center, cross examines Stormy Daniels, far right, whose real name is Stephanie Clifford, as former President Donald Trump, left, looks on with Judge Juan Merchan presiding during Trump's trial in Manhattan criminal court, Tuesday, May 7, 2024, in New York. (Elizabeth Williams via AP)

NEW YORK (AP) — Donald Trump squirmed and scowled, shook his head and muttered as Stormy Daniels described the unexpected sex she says they had nearly two decades ago, saying she remembered “trying to think of anything other than what was happening.”

In this courtroom sketch, defense attorney Susan Necheles, center, cross examines Stormy Daniels, far right, whose real name is Stephanie Clifford, as former President Donald Trump, left, looks on with Judge Juan Merchan presiding during Trump's trial in Manhattan criminal court, Tuesday, May 7, 2024, in New York. (Elizabeth Williams via AP)

Judge Juan Merchan presides over proceedings as Stormy Daniels, far right, answers questions on direct examination by assistant district attorney Susan Hoffinger in Manhattan criminal court as former President Donald Trump and defense attorney Todd Blanche look on, Tuesday, May 7, 2024, in New York. (Elizabeth Williams via AP)

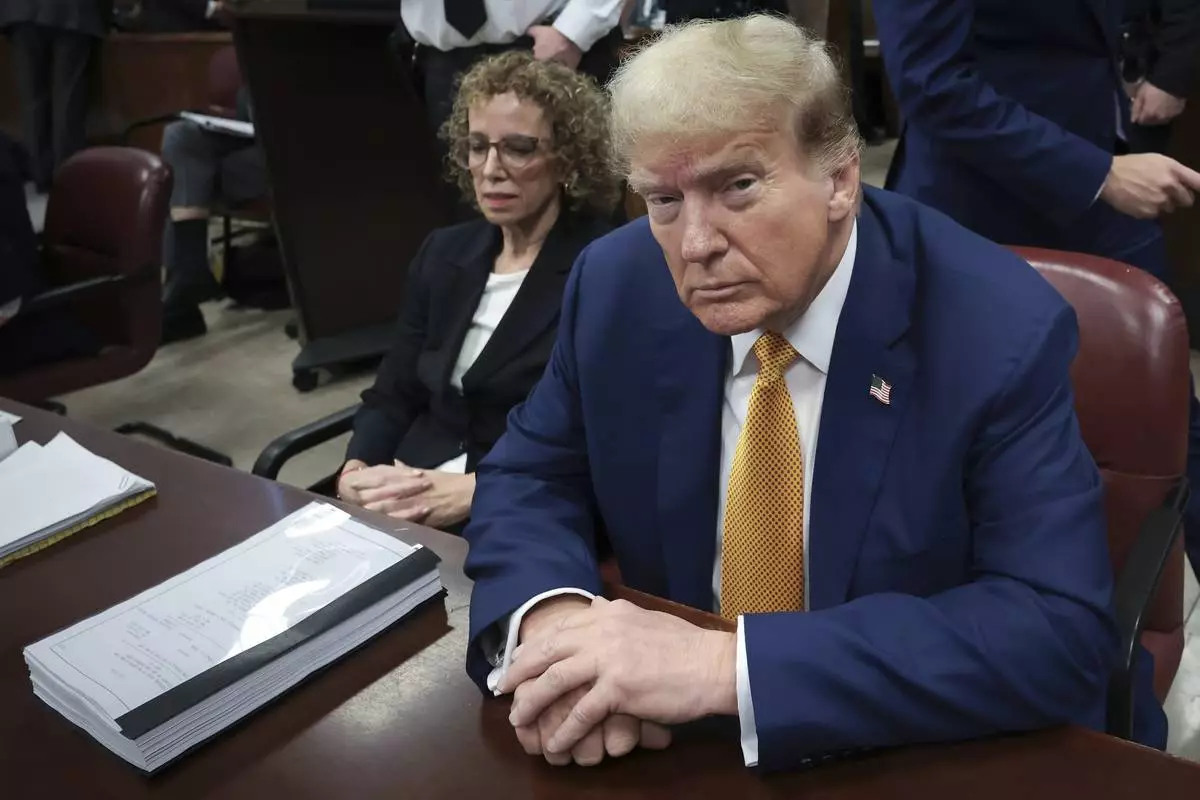

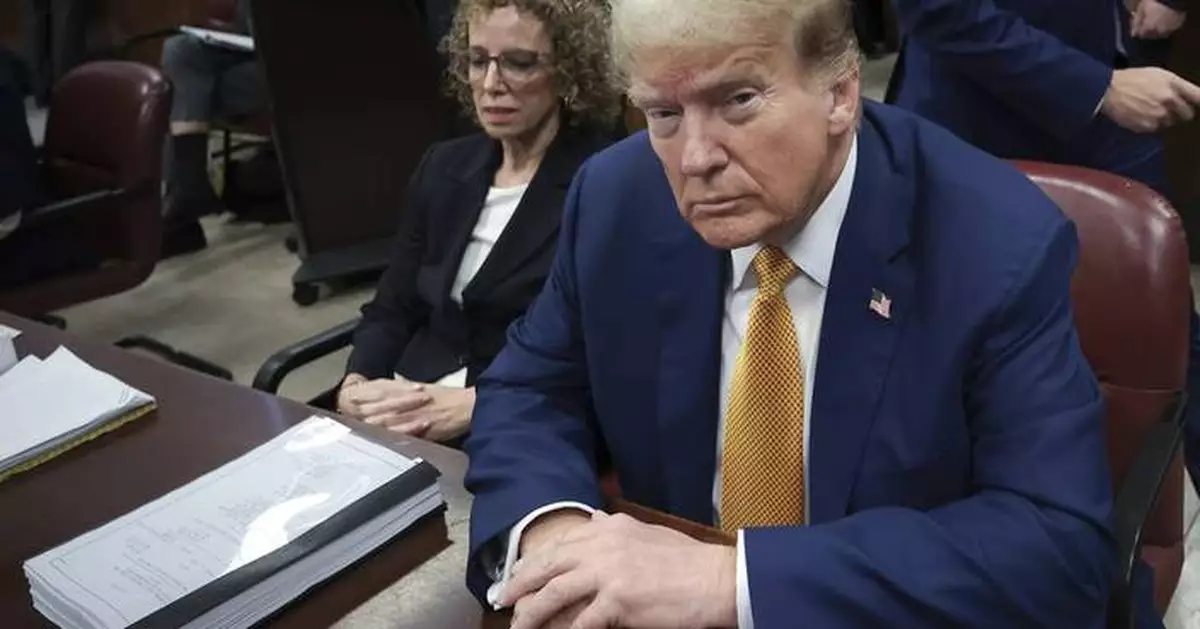

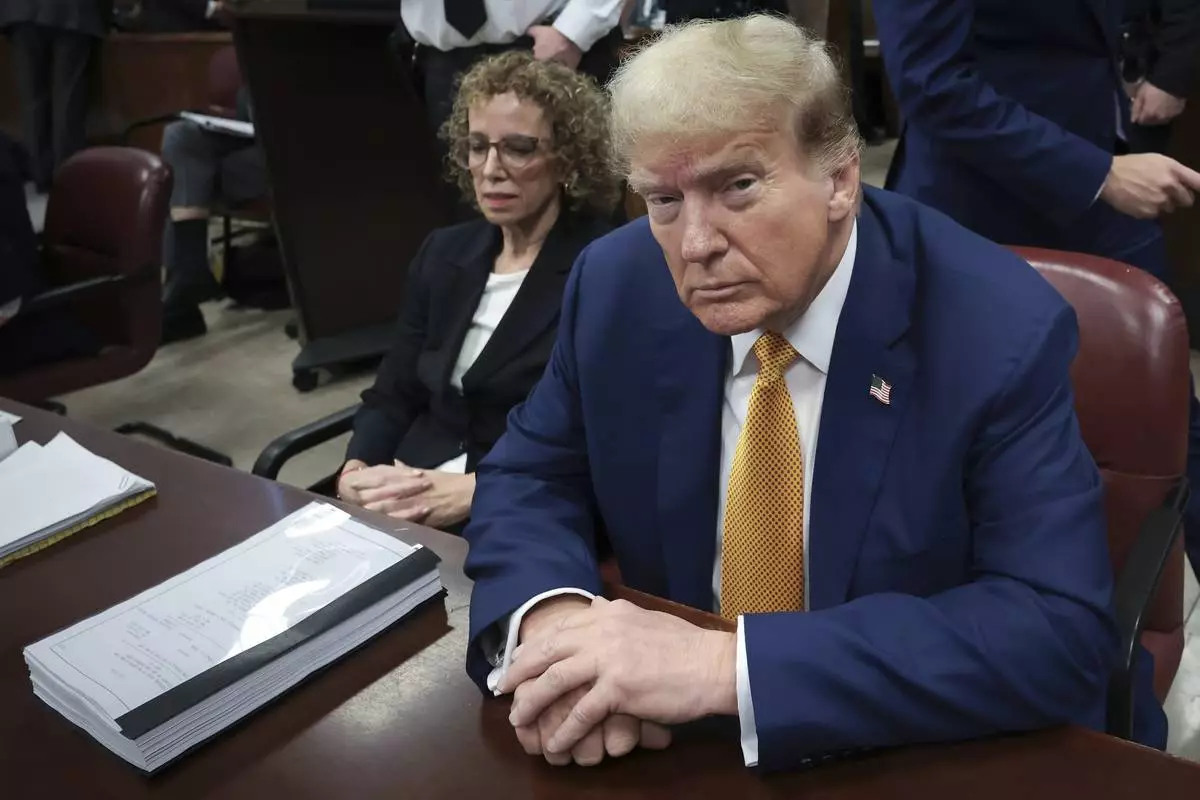

Former President Donald Trump, center, and attorney Susan Necheles, left, attend his trial at Manhattan criminal court on Tuesday, May 7, 2024, in New York. (Win McNamee/Pool Photo via AP)

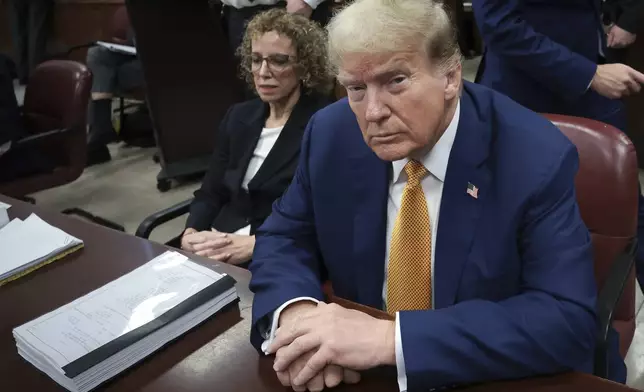

Former President Donald Trump sits in Manhattan Criminal Court on Tuesday, May 7, 2024 in New York. (Win McNamee/Pool Photo via AP)

Years in the making, the in-person showdown between the former president and the porn actor who has become one of his nemeses happened Tuesday in a New York courtroom that has become the plainspoken stage for the historic spectacle of Trump’s hush money trial, where the gravitas of the first-ever criminal trial of a former U.S. commander-in-chief butts up against a crass and splashy tale of sex, tabloids and payoffs.

It’s often said that actual trials are not like the TV drama versions, and in that way, this one is no exception — a methodical and sometimes static proceeding of questions, answers and rules. But if Tuesday’s testimony wasn’t an electric scene of outbursts and tears, it was no less stunning for its sheer improbability.

Daniels’ testimony had been speculated about for as long as Trump has been under indictment. But when it would happen was still a mystery until Tuesday morning, when her lawyer Clark Brewster confirmed in an email to an Associated Press reporter that it was “likely today.”

But even after the trial resumed, Daniels still had to wait.

The first witness of the day was a publishing executive who read passages from some of Trump’s business books.

Then, when the judge asked for the prosecution’s next witness, Assistant District Attorney Susan Hoffinger matter-of-factly declared, “The people call Stormy Daniels.”

Daniels strode briskly to the stand, not looking at Trump, her shoes clunking on the floor. The former president stared straight ahead until the moment she had passed his spot at the defense table, then tilted his head slightly in her direction.

As is standard in court proceedings, Daniels was asked if she saw Trump in the courtroom and to identify him. Before answering, Daniels, wearing eyeglasses, shuffled in her seat for a beat, looking around the courtroom. She then pointed toward him, describing his navy suit coat and gold tie, and said he was sitting at the defense table. Trump looked straight forward, lips pursed.

Dozens of reporters and a handful of public observers packed the courtroom gallery.

In one row alone: CNN anchor Erin Burnett, MSNBC host Lawrence O’Donnell and Andrew Giuliani, the son of Trump’s former lawyer Rudy Giuliani, who wore a media credential from WABC Radio, where he and his dad host shows. Trump’s son Eric sat elsewhere in the courtroom.

As she testified, Daniels spoke confidently and at a rapid clip, the sound of reporters typing reaching a frenetic tempo.

She spoke so quickly, at least six times during her testimony she was asked to slow down so a court stenographer could keep pace.

Jurors seemed as attentive as they’ve been all trial as Daniels recounted her path from aspiring veterinary student to porn actor.

One juror smiled when Daniels mentioned one of the ways into the industry was by winning a contest, like “Ms. Nude North America.” Another juror’s eyes widened as he read along on the monitor displaying a Truth Social post in which Trump said he “did NOTHING wrong” and used an insulting nickname to disparage Daniels' looks.

Trump denies her claims and has pleaded not guilty in the case, in which he’s charged with falsifying business records related to a $130,000 payment to Daniels to keep quiet.

Many of the jurors jotted notes throughout her testimony, peering up from notepads and alternating their gaze from Daniels in the witness box to the lawyers questioning her from a lectern.

Guided by prosecutors, Daniels drew a detailed scene of her alleged evening with Trump at a hotel suite in Lake Tahoe in 2006, delving frankly into details that Judge Juan M. Merchan would later concede “should probably have been left unsaid.”

She recalled entering the sprawling suite to find Trump in a pair of silk pajamas. She sheepishly admitted to snooping through his bathroom toiletries in the bathroom, finding a pair of golden tweezers. Daniels even acted out part of her interaction with Trump, reclining back in the witness box to demonstrate how she said he was positioned on the bed of his hotel suite when she emerged from the restroom.

Her willingness to provide extra details prompted an usual moment: Trump’s lawyers consented to allowing a prosecutor to meet with Daniels in a side room, during a break in testimony, to give her some instructions to — as Judge Merchan put it — “make sure the witness stays focused on the question, gives the answer and does not give any unnecessary narrative.”

Out of the earshot of the jury, or the reporters in the room, Merchan also asked Trump's lawyers to stop him from cursing as Daniels spoke.

“I understand that your client is upset at this point, but he is cursing audibly, and he is shaking his head visually and that’s contemptuous. It has the potential to intimidate the witness and the jury can see that,” the judge said. “I am speaking to you here at the bench because I don’t want to embarrass him,” Merchan added.

“I will talk to him,” said one of Trump's lawyers, Todd Blanche.

Peppy and loquacious when she was being questioned by prosecutors, Daniels was feistier on cross-examination, digging in when defense lawyer Susan Necheles questioned her credibility and motives.

Daniels forcefully denied Necheles’ suggestion that she had tried to extort Trump, answering the lawyer’s contention: “False.”

Daniels left the witness stand just before 4:30 p.m. She didn’t look at Trump as she trod past. He didn’t look at her, either, instead leaning over to whisper to Necheles.

Moments later, Merchan adjourned court until Thursday — with Wednesday the trial’s usual off day. Trump left the courtroom with his entourage of lawyers and aides.

“This was a very revealing day in court. Any honest reporter would say that,” Trump said to journalists in the hallway outside the courtroom. He is limited by court order from saying much more about Daniels to the media.

Inside the courtroom, the witnesses to history reconciled their thoughts, gathered their belongings and waited for Trump to leave the building, so they could, too.

Stormy Daniels, center, exits the courthouse at Manhattan criminal court in New York, Tuesday, May 7, 2024. Porn actor Daniels, whose real name is Stephanie Clifford, took the stand mid-morning Tuesday and testified about her alleged sexual encounter with former President Donald Trump in 2006, among other things. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

In this courtroom sketch, defense attorney Susan Necheles, center, cross examines Stormy Daniels, far right, whose real name is Stephanie Clifford, as former President Donald Trump, left, looks on with Judge Juan Merchan presiding during Trump's trial in Manhattan criminal court, Tuesday, May 7, 2024, in New York. (Elizabeth Williams via AP)

Judge Juan Merchan presides over proceedings as Stormy Daniels, far right, answers questions on direct examination by assistant district attorney Susan Hoffinger in Manhattan criminal court as former President Donald Trump and defense attorney Todd Blanche look on, Tuesday, May 7, 2024, in New York. (Elizabeth Williams via AP)

Former President Donald Trump, center, and attorney Susan Necheles, left, attend his trial at Manhattan criminal court on Tuesday, May 7, 2024, in New York. (Win McNamee/Pool Photo via AP)

Former President Donald Trump sits in Manhattan Criminal Court on Tuesday, May 7, 2024 in New York. (Win McNamee/Pool Photo via AP)

A long-planned series of Catholic pilgrimages has begun across the United States this weekend, with pilgrims embarking on four routes before converging on Indianapolis in two months for a major gathering focusing on Eucharistic rites and devotions.

The National Eucharistic Pilgrimage is beginning with Masses and other events in California, Connecticut, Minnesota and Texas. A small group of pilgrims plan to walk entire routes, but most participants are expected to take part for smaller segments. Each route goes along country roads and through city centers, with multiple stops at parishes, shrines and other sites.

Although it was forged amid a recent debate among bishops over whether to refuse Communion to U.S. politicians who don’t oppose abortion, the pilgrimage is a revival of a historic Catholic tradition that faded by the mid-20th century.

Each procession is being led by a priest holding a monstrance — typically a sunburst-patterned vessel that displays the host, or bread wafer consecrated by a priest at Mass.

The Catholic Church teaches the “whole Christ is truly present — body, blood, soul, and divinity — under the appearances of bread and wine,” according to the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. As a result, the consecrated host becomes an object of devotion.

“The Eucharist is actually Jesus, so for us to walk with Jesus is actually a witness to our faith in a prayerful action for unity, for peace," said Tim Glemkowski, CEO of the National Eucharistic Congress, the umbrella organization for the events.

The four lengthy pilgrimages appear to be unprecedented, Glemkowski said.

“It’s hard in a 2,000-year-old church to do something for the first time, but a procession this long, with this many people in it, may be the first time this has been attempted in the history of the Catholic Church,” Glemkowski said.

Some pilgrims were embarking Sunday from the headwaters of the Mississippi River in Minnesota. Others planned to embark from a cathedral in Brownsville, Texas, or cross San Francisco's Golden Gate Bridge.

In New Haven, Connecticut, commemorations began with a Saturday night Mass and a mini-procession around St. Mary's Church, which is the burial site of the 19th century founder of the Knights of Columbus fraternal organization, the Rev. Michael McGivney. After an all-night vigil of prayer and adoration, pilgrims were bringing the host to another New Haven church and later to a boat to carry it to the city of Bridgeport and the next leg of the pilgrimage.

The pilgrimage amounts to an effort to revive a type of mass devotion that was once more common in past generations of Catholicism in the U.S. and beyond.

The pilgrimages — and the concluding National Eucharistic Congress, expected to draw tens of thousands to Lucas Oil Stadium in Indianapolis in July — is being funded by private donors, sponsors and ticket sales, Glemkowski said. The budget for the National Eucharistic Revival — which is actually a three-year process that has included parish activities as well as the pilgrimages and congress — is about $23 million, with $14 million of that for the congress, he said.

There have been nine previous U.S. gatherings under the name of the National Eucharistic Congress — but none since 1941.

“We just kind of lost track of this tradition,” Glemkowski said. “We’re bringing it back in a way that fits this time.”

Glemkowski said the pilgrimage is not a march and would avoid politics. “That message of unity and peace and just focus on Christ is paramount,” he said.

The idea for these pilgrimages sprang from deliberations among U.S. bishops.

Their 2021 document, “The Mystery of the Eucharist in the Life of the Church,” arose amid debate over whether bishops should withhold Communion from Catholic politicians who supported abortion rights. The document ultimately did not directly address that, though it called on Catholics to examine whether they align with church teachings and said bishops have a “special responsibility” to respond to "public actions at variance with the visible Communion of the church and the moral law.”

At the same time, the document reflected bishops’ worries that many Catholics don’t know or accept the church’s teachings about the significance of the sacrament, though surveys have given mixed results on that question.

Timothy Kelly, professor of history at Saint Vincent College in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, said it's an open question how many participants the pilgrimage will draw. His 2009 book, “The Transformation of American Catholicism," documents the rise and decline of stadium-sized devotional activities such as Eucharistic adoration in 20th century Pittsburgh.

Many early 20th century Catholics were from immigrant communities, and they often gathered at times of flood, war or other crises. “A lot of times in the older demonstrations, the message seemed to be outward toward the broader community — the Catholics bearing witness to their presence and their faith, but also saying, ‘We’re here and we matter.’”

But participation began dropping sharply by the 1950s. “What happened was the laity stopped being interested in it,” Kelly said.

The Eucharistic pilgrimage, he said, appears to be attracting the most interest in Catholic media sympathetic with other efforts to revive older traditions, such as the Latin Mass.

“Which makes me curious, how well does this resonate within the broader Catholic community?” he said.

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

The Eucharistic host is held in a monstrance during a procession outside of St. Mary's Church, Saturday, May 18, 2024, in New Haven, Conn. The Eucharistic Procession from St. Mary's Church is one of four pilgrimage routes crossing the country and converging at the National Eucharistic Congress in Indianapolis, July 16. (AP Photo/Jessica Hill)

The Eucharistic host is held in a monstrance during a procession outside of St. Mary's Church, Saturday, May 18, 2024, in New Haven, Conn. The Eucharistic Procession from St. Mary's Church is one of four pilgrimage routes crossing the country and converging at the National Eucharistic Congress in Indianapolis, July 16. (AP Photo/Jessica Hill)

The Eucharistic host is held in a monstrance during a procession outside of St. Mary's Church, Saturday, May 18, 2024, in New Haven, Conn. The Eucharistic Procession from St. Mary's Church is one of four pilgrimage routes crossing the country and converging at the National Eucharistic Congress in Indianapolis, July 16. (AP Photo/Jessica Hill)

The Eucharistic host is held in a monstrance during a Pentecost Vigil at Blessed Michael McGivney Parish at St. Mary's Church, Saturday, May 18, 2024, in New Haven, Conn. The Eucharistic Procession from St. Mary's Church is one of four pilgrimage routes crossing the country and converging at the National Eucharistic Congress in Indianapolis, July 16. (AP Photo/Jessica Hill)

Two boys hold candles during a Pentecost Vigil at Blessed Michael McGivney Parish at St. Mary's Church, Saturday, May 18, 2024, in New Haven, Conn. The Eucharistic Procession from St. Mary's Church is one of four pilgrimage routes crossing the country and converging at the National Eucharistic Congress in Indianapolis, July 16. (AP Photo/Jessica Hill)

The Most Rev. Christopher J. Coyne, archbishop of Hartford, leads a Pentecost Vigil at Blessed Michael McGivney Parish in St. Mary's Church, Saturday, May 18, 2024, in New Haven, Conn. The Eucharistic Procession from St. Mary's Church is one of four pilgrimage routes crossing the country and converging at the National Eucharistic Congress in Indianapolis, July 16. (AP Photo/Jessica Hill)

The Most Rev. Christopher J. Coyne, archbishop of Hartford, raises a chalice during a Pentecost Vigil at Blessed Michael McGivney Parish in St. Mary's Church, Saturday, May 18, 2024, in New Haven, Conn. The Eucharistic Procession from St. Mary's Church is one of four pilgrimage routes crossing the country and converging at the National Eucharistic Congress in Indianapolis, July 16. (AP Photo/Jessica Hill)

Altar boys hold their hands close to a flame to keep it from blowing out during a Pentecost Vigil at Blessed Michael McGivney Parish in St. Mary's Church, Saturday, May 18, 2024, in New Haven, Conn. The Eucharistic Procession from St. Mary's Church is one of four pilgrimage routes crossing the country and converging at the National Eucharistic Congress in Indianapolis, July 16. (AP Photo/Jessica Hill)

People pray during a Pentecost Vigil at St. Mary's Church, Saturday, May 18, 2024, in New Haven, Conn. The Eucharistic Procession from St. Mary's Church is one of four pilgrimage routes crossing the country and converging at the National Eucharistic Congress in Indianapolis, July 16. (AP Photo/Jessica Hill)

People kneel during a Pentecost Vigil at Blessed Michael McGivney Parish at St. Mary's Church, Saturday, May 18, 2024, in New Haven, Conn. The Eucharistic Procession from St. Mary's Church is one of four pilgrimage routes crossing the country and converging at the National Eucharistic Congress in Indianapolis, July 16. (AP Photo/Jessica Hill)

Nuns listen during a Pentecost Vigil at Blessed Michael McGivney Parish in St. Mary's Church, Saturday, May 18, 2024, in New Haven, Conn. The Eucharistic Procession from St. Mary's Church is one of four pilgrimage routes crossing the country and converging at the National Eucharistic Congress in Indianapolis, July 16. (AP Photo/Jessica Hill)

The Most Rev. Christopher J. Coyne, archbishop of Hartford, walks in a procession during a Pentecost Vigil at Blessed Michael McGivney Parish in St. Mary's Church, Saturday, May 18, 2024, in New Haven, Conn. The Eucharistic Procession from St. Mary's Church is one of four pilgrimage routes crossing the country and converging at the National Eucharistic Congress in Indianapolis on July 16. (AP Photo/Jessica Hill)