JAKARTA, Indonesia (AP) — A wealthy ex-general with ties to both Indonesia’s popular outgoing president and the country's dictatorial past will be inaugurated as its leader Sunday. He has promised to continue his predecessor's widely popular policies, but his human rights record has activists, and some analysts, concerned about the future of Indonesia’s democracy.

At the election in February, Prabowo Subianto, 73, presented himself as heir to the immensely popular President Joko Widodo, the first Indonesian president to emerge from outside the political and military elite. Subianto, who was then defense minister, vowed to continue the modernization agenda that has brought rapid growth and vaulted Indonesia into the ranks of middle-income countries.

Click to Gallery

FILE - Indonesian Defense Minister and president-elect Prabowo Subianto, center, salutes to journalists in front of his running mate Gibran Rakabuming Raka, rear center, the eldest son of Indonesian President Joko Widodo, during their formal declaration as president and vice president-elect at the General Election Commission building in Jakarta, Indonesia, Wednesday, April 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Achmad Ibrahim, File)

FILE - Five activists of the unrecognized People's Democratic Party, including Budiman Sudjatmiko, center, raise their fists while posing for photographers in front of a room at the Central Jakarta district court Monday, April 28, 1997. (AP Photo/Ujang, File)

FILE- Retired Indonesian Lt. Gen. Prabowo Subianto, former leader of the elite Kopassus special forces, tells his side of the story during his first news conference since his return to Jakarta, May 9, 2000, where he denied masterminding the May 1998 riots and violence in Aceh, Irian Jaya, and East Timor. (AP Photo/Charles Dharapak, File)

FILE - Defense Minister and president-elect Prabowo Subianto,left, shares a light moment with President Joko Widodo during the ceremony marking Indonesia's 79th anniversary of independence at the new presidential palace in the future capital of Nusantara, a city still under construction on the island of Borneo, Saturday, Aug. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Achmad Ibrahim, File)

FILE - Indonesian Defense Minister and president-elect Prabowo Subianto, center, salutes to journalists in front of his running mate Gibran Rakabuming Raka, rear center, the eldest son of Indonesian President Joko Widodo, during their formal declaration as president and vice president-elect at the General Election Commission building in Jakarta, Indonesia, Wednesday, April 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Achmad Ibrahim, File)

FILE - Indonesian Defense Minister and president-elect Prabowo Subianto, left, shakes hands with his running mate Gibran Rakabuming Raka, the eldest son of Indonesian President JokoWidodo, during their formal declaration as president and vice president-elect at the General Election Commission building in Jakarta, Indonesia, Wednesday, April 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara, File)

FILE - Indonesian Defense Minister Prabowo Subianto pauses after being awarded honorary rank of four-star general by President Joko Widodo during a ceremony at the Armed Forces Headquarters in Jakarta, Indonesia, Wednesday, Feb. 28, 2024. (AP Photo/Achmad Ibrahim, File)

FILE - Indonesian Defense Minister Prabowo Subianto waves at journalists in Jakarta, Indonesia, Tuesday, Feb. 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Achmad Ibrahim, File)

FILE - Indonesian Defense Minister and presidential frontrunner Prabowo Subianto greets supporters after visiting his father's grave in Jakarta, Indonesia Thursday, Feb. 15, 2024. (AP Photo/Tatan Syuflana, File)

In a speech last month, Subianto, who’s also the chair of the Gerindra Party, reminded party members to always remain loyal to the nation, not to him. He also vowed his unwavering commitment to defend the people, even at the cost of his life.

“Once you smell I’m on the wrong path, please leave me,” Subianto said, “My life, my oath … I want to die for the truth, I want to die defending my people, I want to die defending the poor, I want to die defending the honor of the Indonesian nation. I have no doubt.”

But Subianto will enter office with unresolved questions about the costs of rapid growth for the environment and traditional communities, as well as his own links to torture, disappearances and other human rights abuses in the final years of the brutal Suharto dictatorship, which he served as a lieutenant general.

Other than promising continuity, Subianto has laid out few concrete plans, leaving observers uncertain about what his election will mean for the country’s economy and its still-maturing democracy.

A former rival of Widodo who lost two presidential races to him, Subianto embraced the popular leader to run as his heir, even choosing Widodo’s son as his running mate, a decision that ran up against constitutional age limits and has activists worried about an emerging political dynasty in the 25-year-old democracy.

But for now, he appears to enjoy widespread support. He secured a majority in the election on Feb. 14, winning 59%, or more than 96 million votes in a three-way race, more than enough for victory without a runoff.

Subianto was born in 1951 to one of Indonesia’s most powerful families, the third of four children. His father, Sumitro Djojohadikusumo, was an influential politician, and a minister under Presidents Sukarno and Suharto.

Subianto’s father first worked for Sukarno, the leader of Indonesia’s quest for independence from the Dutch, as well as the first president. But Djojohadikusumo later turned against the leader and was forced into exile. Subianto spent most of his childhood overseas and speaks French, German, English and Dutch.

The family returned to Indonesia after General Suharto came to power in 1967 following a failed left-wing coup. Suharto dealt brutally with dissenters and was accused of stealing billions of dollars of state funds for himself, family and close associates. Suharto dismissed the allegations even after leaving office in 1998.

Subianto enrolled in Indonesia’s Military Academy in 1970, graduating in 1974 and serving in the military for nearly three decades. In 1976, Subianto joined the Indonesian National Army Special Force, called Kopassus, and was commander of a group that operated in what is now East Timor.

Human rights groups have claimed that Subianto was involved in a series of human rights violations in East Timor in the 1980s and 1990s, when Indonesia occupied the now-independent nation. Subianto has denied those allegations.

Subianto and other members of Kopassus were banned from traveling to the U.S. over the alleged human rights abuses they committed against the people of East Timor. The ban remained in place until 2020, when it was effectively lifted, enabling him to visit the U.S. as Indonesia’s defense minister.

In 1983, he married Suharto’s daughter, Siti Hediati Hariyadi.

Following further allegations of human rights abuses, Subianto was forced out of the military. He was dishonorably discharged in 1998, after Kopassus soldiers kidnapped and tortured political opponents of Suharto. Of 22 activists kidnapped that year, 13 remain missing. Several of his men were tried and convicted, but Subianto never faced trial.

He never commented on these accusations but went into self-imposed exile in Jordan in 1998.

A number of former democracy activists have joined his campaign, including Agus Jabo and Budiman Sudjatmiko, who in 1998 were listed as survivors of the abductions of democracy activists. Sudjatmiko left the governing Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle to join Subianto's campaign team.

During a campaign event in January, he apologized publicly to the two former activists.

“I'm sorry ... I was chasing you in the past,” Subianto said, adding that he did so “on the orders” of his superiors.

Sudjatmiko said that reconciliation is necessary to move forward, and that international focus on Subianto’s human rights record was overblown. “Developed countries don’t like leaders from developing countries who are brave, firm and strategic,” he said.

Subianto returned from Jordan in 2008, and helped to found the Gerinda Party. He ran for the presidency twice, losing to Widodo both times. He refused to acknowledge the results at first, but accepted Widodo’s offer of the defense minister position in 2019, in a bid for unity.

Adhi Priamarizki, a researcher at Singapore's S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, said that while many right activists have pointed out Subianto's checkered past, “there are a lot of factors that actually can affect how he can or he will govern the country.”

“I would say that there’s going to be a good check and balance system, hopefully, fingers crossed,” Priamarizki said, “But the most important thing is to ensure that civil society has space in order to provide or to be at the check and balance systems.”

In the most recent election, Subianto respected the democratic process.

He has vowed to continue Widodo’s economic development plans, which capitalized on Indonesia’s abundant nickel, coal, oil and gas reserves, leading Southeast Asia’s biggest economy through a decade of rapid growth and modernization that vastly expanded its networks of roads and railways.

That includes includes the $30 billion project to build a new capitol city called Nusantara. A report by a coalition of NGOs claimed that Subianto’s family would profit from the Nusantara project, thanks to land and mining interests the family holds on East Kalimantan, the province where the new city is located. A member of the family denied the report’s allegations.

Subianto and his family also have business ties to Indonesia’s palm oil, coal and gas, mining, agriculture and fishery industries.

The former rivals became tacit allies: Indonesian presidents don’t typically endorse candidates, but Subianto chose Widodo’s son, 36-year-old Surakarta Mayor Gibran Rakabuming Raka, as his vice presidential running mate, and Widodo coyly favored Subianto over the candidate of his own former party.

Subianto has also cultivated close ties with hard-line Islamists as a way of undermining Widodo in the 2014 and 2019 elections.

But for the 2024 election, Subianto projected a softer image that has resonated with Indonesia’s large youth population, including videos of him dancing on stage and ads showing digital anime-like renderings of him roller-skating through Jakarta’s streets.

“We will be the president and vice president and government for all Indonesian people,” said Subianto during his victory speech.

Associated Press writer Edna Tarigan contributed to this report.

Find more AP Asia-Pacific coverage at https://apnews.com/hub/asia-pacific

FILE - Five activists of the unrecognized People's Democratic Party, including Budiman Sudjatmiko, center, raise their fists while posing for photographers in front of a room at the Central Jakarta district court Monday, April 28, 1997. (AP Photo/Ujang, File)

FILE- Retired Indonesian Lt. Gen. Prabowo Subianto, former leader of the elite Kopassus special forces, tells his side of the story during his first news conference since his return to Jakarta, May 9, 2000, where he denied masterminding the May 1998 riots and violence in Aceh, Irian Jaya, and East Timor. (AP Photo/Charles Dharapak, File)

FILE - Defense Minister and president-elect Prabowo Subianto,left, shares a light moment with President Joko Widodo during the ceremony marking Indonesia's 79th anniversary of independence at the new presidential palace in the future capital of Nusantara, a city still under construction on the island of Borneo, Saturday, Aug. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Achmad Ibrahim, File)

FILE - Indonesian Defense Minister and president-elect Prabowo Subianto, center, salutes to journalists in front of his running mate Gibran Rakabuming Raka, rear center, the eldest son of Indonesian President Joko Widodo, during their formal declaration as president and vice president-elect at the General Election Commission building in Jakarta, Indonesia, Wednesday, April 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Achmad Ibrahim, File)

FILE - Indonesian Defense Minister and president-elect Prabowo Subianto, left, shakes hands with his running mate Gibran Rakabuming Raka, the eldest son of Indonesian President JokoWidodo, during their formal declaration as president and vice president-elect at the General Election Commission building in Jakarta, Indonesia, Wednesday, April 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara, File)

FILE - Indonesian Defense Minister Prabowo Subianto pauses after being awarded honorary rank of four-star general by President Joko Widodo during a ceremony at the Armed Forces Headquarters in Jakarta, Indonesia, Wednesday, Feb. 28, 2024. (AP Photo/Achmad Ibrahim, File)

FILE - Indonesian Defense Minister Prabowo Subianto waves at journalists in Jakarta, Indonesia, Tuesday, Feb. 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Achmad Ibrahim, File)

FILE - Indonesian Defense Minister and presidential frontrunner Prabowo Subianto greets supporters after visiting his father's grave in Jakarta, Indonesia Thursday, Feb. 15, 2024. (AP Photo/Tatan Syuflana, File)

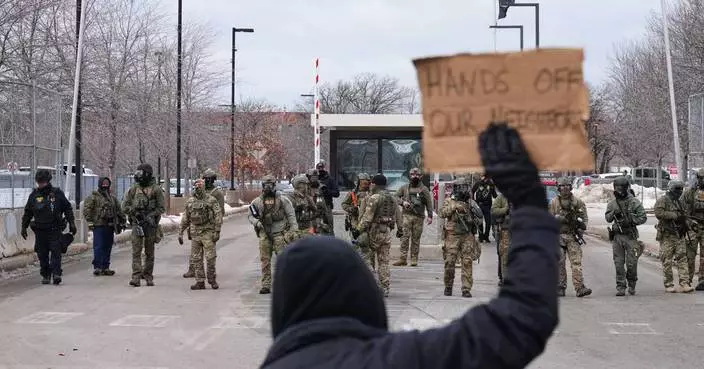

Federal immigration agents deployed to Minneapolis have used aggressive crowd-control tactics that have become a dominant concern in the aftermath of the deadly shooting of a woman in her car last week.

They have pointed rifles at demonstrators and deployed chemical irritants early in confrontations. They have broken vehicle windows and pulled occupants from cars. They have scuffled with protesters and shoved them to the ground.

The government says the actions are necessary to protect officers from violent attacks. The encounters in turn have riled up protesters even more, especially as videos of the incidents are shared widely on social media.

What is unfolding in Minneapolis reflects a broader shift in how the federal government is asserting its authority during protests, relying on immigration agents and investigators to perform crowd-management roles traditionally handled by local police who often have more training in public order tactics and de-escalating large crowds.

Experts warn the approach runs counter to de-escalation standards and risks turning volatile demonstrations into deadly encounters.

The confrontations come amid a major immigration enforcement surge ordered by the Trump administration in early December, which sent more than 2,000 officers from across the Department of Homeland Security into the Minneapolis-St. Paul area. Many of the officers involved are typically tasked with arrests, deportations and criminal investigations, not managing volatile public demonstrations.

Tensions escalated after the fatal shooting of Renee Good, a 37-year-old woman killed by an immigration agent last week, an incident federal officials have defended as self-defense after they say Good weaponized her vehicle.

The killing has intensified protests and scrutiny of the federal response.

On Monday, the American Civil Liberties Union of Minnesota asked a federal judge to intervene, filing a lawsuit on behalf of six residents seeking an emergency injunction to limit how federal agents operate during protests, including restrictions on the use of chemical agents, the pointing of firearms at non-threatening individuals and interference with lawful video recording.

“There’s so much about what’s happening now that is not a traditional approach to immigration apprehensions,” said former Immigration and Customs Enforcement Director Sarah Saldaña.

Saldaña, who left the post at the beginning of 2017 as President Donald Trump's first term began, said she can't speak to how the agency currently trains its officers. When she was director, she said officers received training on how to interact with people who might be observing an apprehension or filming officers, but agents rarely had to deal with crowds or protests.

“This is different. You would hope that the agency would be responsive given the evolution of what’s happening — brought on, mind you, by the aggressive approach that has been taken coming from the top,” she said.

Ian Adams, an assistant professor of criminal justice at the University of South Carolina, said the majority of crowd-management or protest training in policing happens at the local level — usually at larger police departments that have public order units.

“It’s highly unlikely that your typical ICE agent has a great deal of experience with public order tactics or control,” Adams said.

DHS Secretary Tricia McLaughlin said in a written statement that ICE officer candidates receive extensive training over eight weeks in courses that include conflict management and de-escalation. She said many of the candidates are military veterans and about 85% have previous law enforcement experience.

“All ICE candidates are subject to months of rigorous training and selection at the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center, where they are trained in everything from de-escalation tactics to firearms to driving training. Homeland Security Investigations candidates receive more than 100 days of specialized training," she said.

Ed Maguire, a criminology professor at Arizona State University, has written extensively about crowd-management and protest- related law enforcement training. He said while he hasn't seen the current training curriculum for ICE officers, he has reviewed recent training materials for federal officers and called it “horrifying.”

Maguire said what he's seeing in Minneapolis feels like a perfect storm for bad consequences.

“You can't even say this doesn't meet best practices. That's too high a bar. These don't seem to meet generally accepted practices,” he said.

“We’re seeing routinely substandard law enforcement practices that would just never be accepted at the local level,” he added. “Then there seems to be just an absence of standard accountability practices.”

Adams noted that police department practices have "evolved to understand that the sort of 1950s and 1960s instinct to meet every protest with force, has blowback effects that actually make the disorder worse.”

He said police departments now try to open communication with organizers, set boundaries and sometimes even show deference within reason. There's an understanding that inside of a crowd, using unnecessary force can have a domino effect that might cause escalation from protesters and from officers.

Despite training for officers responding to civil unrest dramatically shifting over the last four decades, there is no nationwide standard of best practices. For example, some departments bar officers from spraying pepper spray directly into the face of people exercising Constitutional speech. Others bar the use of tear gas or other chemical agents in residential neighborhoods.

Regardless of the specifics, experts recommend that departments have written policies they review regularly.

“Organizations and agencies aren’t always familiar with what their own policies are,” said Humberto Cardounel, senior director of training and technical assistance at the National Policing Institute.

“They go through it once in basic training then expect (officers) to know how to comport themselves two years later, five years later," he said. "We encourage them to understand and know their training, but also to simulate their training.”

Adams said part of the reason local officers are the best option for performing public order tasks is they have a compact with the community.

“I think at the heart of this is the challenge of calling what ICE is doing even policing,” he said.

"Police agencies have a relationship with their community that extends before and after any incidents. Officers know we will be here no matter what happens, and the community knows regardless of what happens today, these officers will be here tomorrow.”

Saldaña noted that both sides have increased their aggression.

“You cannot put yourself in front of an armed officer, you cannot put your hands on them certainly. That is impeding law enforcement actions,” she said.

“At this point, I’m getting concerned on both sides — the aggression from law enforcement and the increasingly aggressive behavior from protesters.”

Law enforcement officers at the scene of a reported shooting Wednesday, Jan. 14, 2026, in Minneapolis. (AP Photo/Adam Gray)

Federal immigration officers confront protesters outside Bishop Henry Whipple Federal Building, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026, in Minneapolis. (AP Photo/Adam Gray)

People cover tear gas deployed by federal immigration officers outside Bishop Henry Whipple Federal Building, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026, in Minneapolis. (AP Photo/Adam Gray)

A man is pushed to the ground as federal immigration officers confront protesters outside Bishop Henry Whipple Federal Building, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026, in Minneapolis. (AP Photo/John Locher)

A woman covers her face from tear gas as federal immigration officers confront protesters outside Bishop Henry Whipple Federal Building, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026, in Minneapolis. (AP Photo/Adam Gray)