SACRAMENTO, Calif. (AP) — When De'Aaron Fox saw that he had 48 points in the fourth quarter in Friday’s 130-126 overtime loss to the Minnesota Timberwolves, teammate Malik Monk told him, “You might as well go get 60.”

The Kings’ guard had 26 points in the fourth quarter and overtime to finish with a franchise-record 60 points, besting Jack Twyman’s 59 points in 1960 and DeMarcus Cousins’ 56-point performance in 2016, which was the most since the franchise moved to Sacramento in 1985.

“I knew I was nice already, so I wouldn’t really say so,” Fox said when asked if he learned anything about himself.

Fox shot 22 of 35 from the field, made 6 of 10 from distance and was 10 of 11 on free throws. He had 21 points at halftime and willed the Kings back from a 20-point second-half deficit as he spurred a 14-0 run to start the fourth quarter.

“I wanted this game to end in the fourth quarter, so I don’t even want to have the opportunity to (get 60 points), but my teammates wanted me to keep going, obviously,” Fox said.

Kings coach Mike Brown said that Fox took it upon himself with Monk and DeMar DeRozan both injured.

“He knew we needed help and he put us on his back, and he almost carried us to the finish line,” Brown said. “He did everything in his power, and it was a spectacular performance by him.”

Fox had the first 60-point game in the NBA this season. Keegan Murray said that it was a little difficult to balance between getting Fox the ball and running the team’s offense, but he thought the Kings “did a solid job of figuring out how to play when he was hot today.”

“When he’s aggressive all the time, he’s extremely tough to stop,” Murray said. “I think that was just a representation of him being aggressive the entire game. And that’s what he’s capable of.”

Fox went shot-for-shot with the Timberwolves’ Anthony Edwards down the stretch, with Edwards’ 36 points leading Minnesota to a resilient win.

“I’ve always felt like he was underrated, underappreciated by everybody,” Edwards said on the Timberwolves television broadcast. “And he showed us today who he is. To me, he’s one of the best point guards in the league, and he showed it.”

“That’s what you love about the game, the best two players on the floor going at each other, so that was fun.”

Fox, who has only made one All-Star team despite averaging over 21 points per game in eight seasons, said he still relishes in his performance even in a loss.

“Obviously, at the end of the day, that type of performance, that type of accomplishment, is nothing to just breathe over and let go,” Fox said. “It’s definitely cool.”

AP NBA: https://apnews.com/hub/nba

Sacramento Kings guard De'Aaron Fox (5) makes a jump shot over Minnesota Timberwolves guard Nickeil Alexander-Walker (9) during the first half of an Emirates NBA Cup basketball game Friday, Nov. 15, 2024, in Sacramento, Calif. (AP Photo/Sara Nevis)

Minnesota Timberwolves guard Anthony Edward, left, talks with Sacramento Kings guard De'Aaron Fox after an Emirates NBA Cup basketball game Friday, Nov. 15, 2024, in Sacramento, Calif. (AP Photo/Sara Nevis)

Sacramento Kings guard De'Aaron Fox calls out plays to his team during a free throw shot during the second half of an Emirates NBA Cup basketball game against the Minnesota Timberwolves, Friday, Nov. 15, 2024, in Sacramento, Calif. (AP Photo/Sara Nevis)

CORPUS CHRISTI, Texas (AP) — In the crucial, chaotic minutes after a gunman in Uvalde, Texas, began firing inside an elementary school, a police officer now accused of failing to protect the children stood by without making a move to stop the carnage, a prosecutor told a jury Tuesday.

School officer Adrian Gonzales arrived at the scene of one of the deadliest school shootings in U.S. history while the teenage assailant was still outside the building. But he did not try to distract or engage him, even when a teacher pointed out the direction of the shooter, special prosecutor Bill Turner said during opening statements of a criminal trial.

The officer only went inside Robb Elementary “after the damage had been done,” Turner said.

Defense attorneys disputed the accusations that Gonzales — one of two officers charged in the aftermath of the 2022 attack — did nothing, saying he radioed for more help and evacuated children as other police arrived.

“The government makes it want to seem like he just sat there,” said defense attorney Nico LaHood. “He did what he could, with what he knew at the time.”

Prosecutors focused sharply on Gonzales’ steps in the minutes after the shooting began and as the first officers arrived. They did not address the hundreds of other local, state and federal officers who arrived and waited more than an hour to confront the gunman, who was eventually killed by a tactical team of officers.

Gonzales, who is no longer a Uvalde schools officer, has pleaded not guilty to 29 counts of child abandonment or endangerment and could be sentenced to a maximum of two years in prison if convicted.

It’s rare for an officer to be criminally charged with not doing more to save lives.

“He could have stopped him, but he didn’t want to be the target,” said Velma Lisa Duran, sister of teacher Irma Garcia, who was among the 19 students and two teachers who were killed.

Duran, who showed up early at the courthouse to watch the beginning of the trial, said authorities stood by while her sister “died protecting children.”

Defense attorneys described an officer who tried to assess where the gunman was while thinking he was being fired on without protection against a high-powered rifle.

Gonzales was among the first group to go into the building before they took fire from Salvador Ramos, the officer’s attorneys said.

“This isn’t a man waiting around. This isn’t a man failing to act,” defense attorney Jason Goss said.

Gonzales and former Uvalde schools police chief Pete Arredondo are the only two officers to face criminal charges over the response. Arredondo’s trial has not been scheduled.

Gonzales, a 10-year veteran of the police force, had extensive active shooter training, the special prosecutor said.

“When a child calls 911, we have a right to expect a response,” Turner said, his voice trembling with emotion.

As Gonzales waited outside, children and teachers hid inside darkened classrooms and grabbed scissors “to confront a gunman,” Turner said. “They did as they had been trained.”

The trial, which is expected to last about two weeks, is sure to be traumatic for the victims’ families. Some are expected to testify, along with law enforcement agents, emergency dispatchers and school employees.

As testimony began, tissue boxes were brought to the families. Some shook their heads as they listened to audio from the first 911 calls, but as they heard the voices become more frantic, the cries in the courtroom were inescapable.

The trial was moved to Corpus Christi after Gonzales’ attorneys argued he could not receive a fair trial in Uvalde.

Some families of the victims have voiced anger that more officers were not charged given that nearly 400 federal, state and local officers converged on the school soon after the attack.

Terrified students inside the classrooms called 911 and parents outside begged for intervention by officers, some of whom could hear shots being fired while they stood in a hallway.

An investigation found 77 minutes passed from the time authorities arrived until they breached the classroom and killed Ramos, who was obsessed with violence and notoriety in the months leading up to the shooting.

State and federal reviews of the shooting cited cascading problems in law enforcement training, communication, leadership and technology, and questioned why officers waited so long.

The officer’s attorneys told jurors that there was plenty of blame to go around — from the lack of security at the school to police policy — and that prosecutors will try to play on their emotions by showing photos from the scene.

“What the prosecution wants you to do is get mad at Adrian. They are going to try to play on your emotions,” Goss said.

“The monster who hurt these children is dead,” he said. “He did not get this justice.”

Prosecutors likely will face a high bar to win a conviction. Juries are often reluctant to convict law enforcement officers for inaction, as seen after the Parkland, Florida, school massacre in 2018. A sheriff’s deputy was acquitted by a jury after being charged with failing to confront the shooter in that attack — the first such prosecution in the U.S. for an on-campus shooting.

Vertuno reported from Austin, Texas. Associated Press journalists Nicholas Ingram in Corpus Christi, Texas; Juan A. Lozano in Houston; and John Seewer in Toledo, Ohio, contributed to this report.

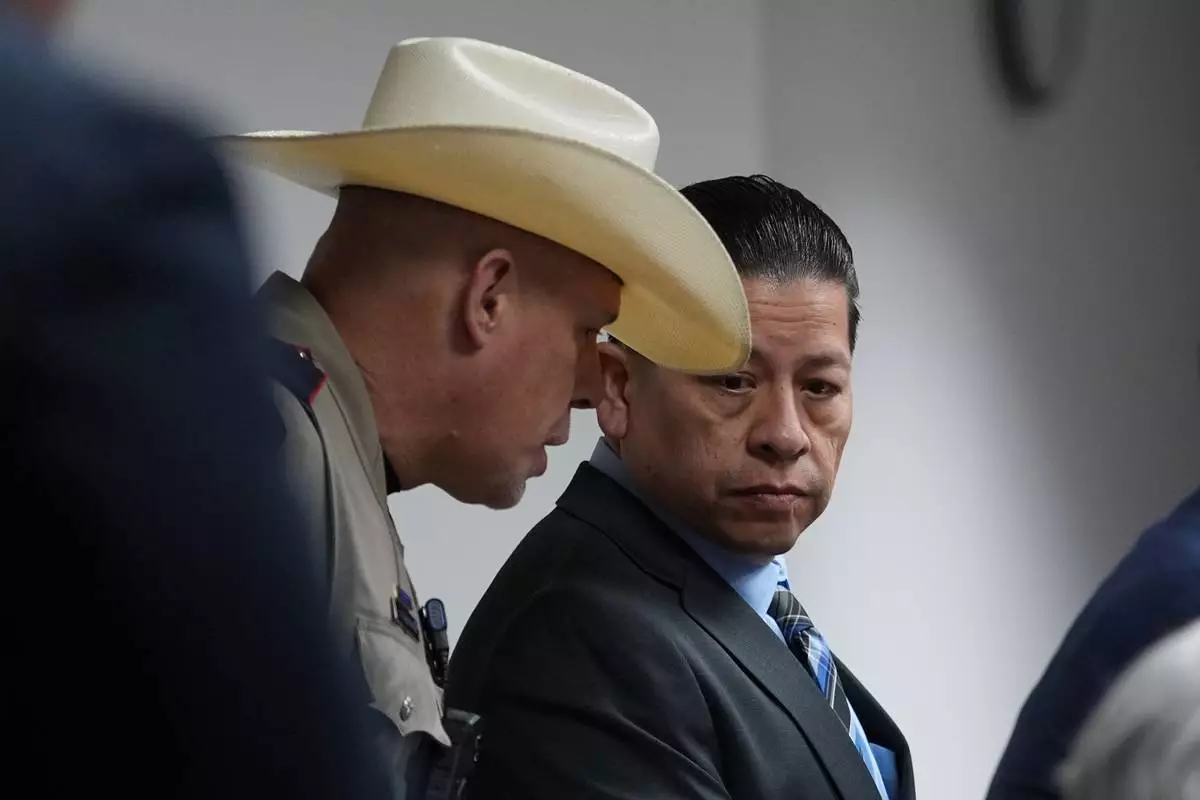

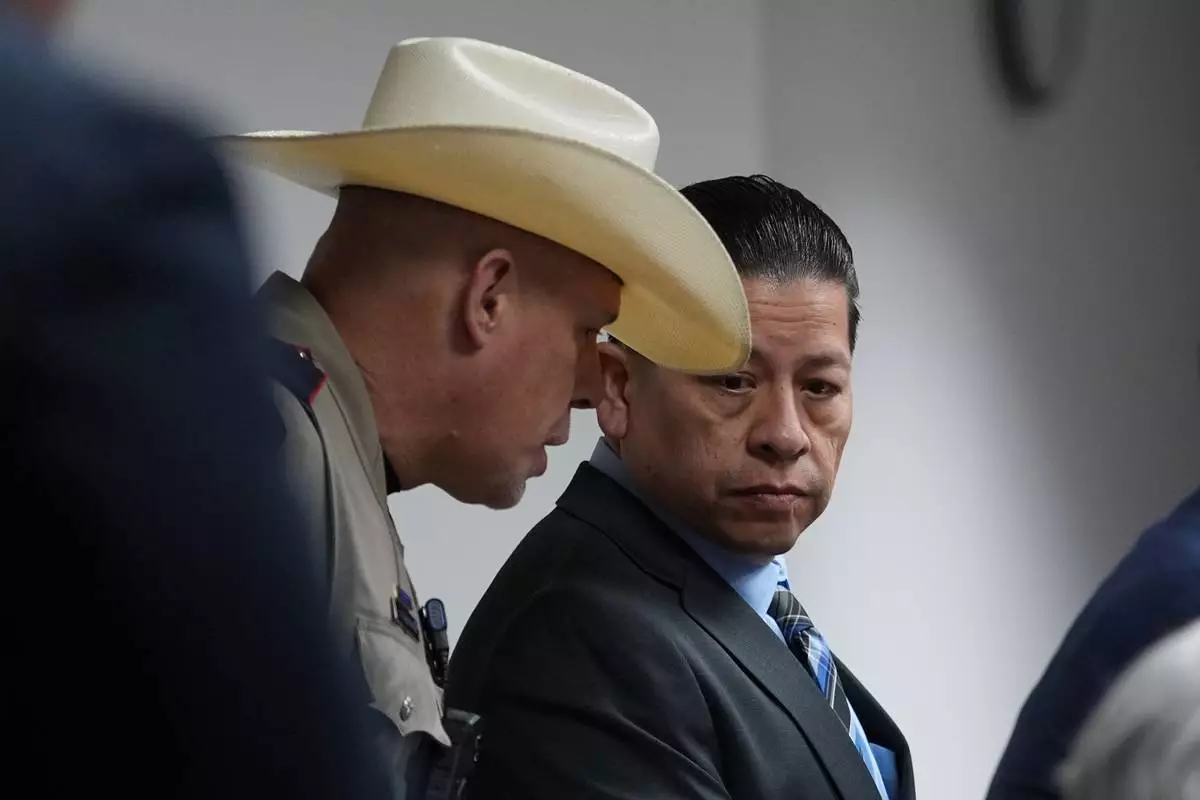

Former Uvalde school district police officer Adrian Gonzales looks back while seated in the courtroom at the Nueces County Courthouse in Corpus Christi, Texas, Tuesday, Jan. 6, 2026. (AP Photo/Eric Gay, Pool)

Former Uvalde school district police officer Adrian Gonzales, right, talks with an officer as he arrives in the courtroom at the Nueces County Courthouse in Corpus Christi, Texas, Tuesday, Jan. 6, 2026. (AP Photo/Eric Gay, Pool)

Family member Jesse Rizo, center, talks to the media before the trial for former Uvalde school district police officer Adrian Gonzales at the Nueces County Courthouse in Corpus Christi, Texas, Tuesday, Jan. 6, 2026. (AP Photo/Eric Gay)

Former Uvalde school district police officer Adrian Gonzales arrives in the courtroom at the Nueces County Courthouse in Corpus Christi, Texas, Tuesday, Jan. 6, 2026. (AP Photo/Eric Gay, Pool)

A man enters the Nueces County Courthouse in Corpus Christi, Texas, as jury selection continues in the trial for former Uvalde school district police officer Adrian Gonzales, Monday, Jan. 5, 2026. (AP Photo/Eric Gay)

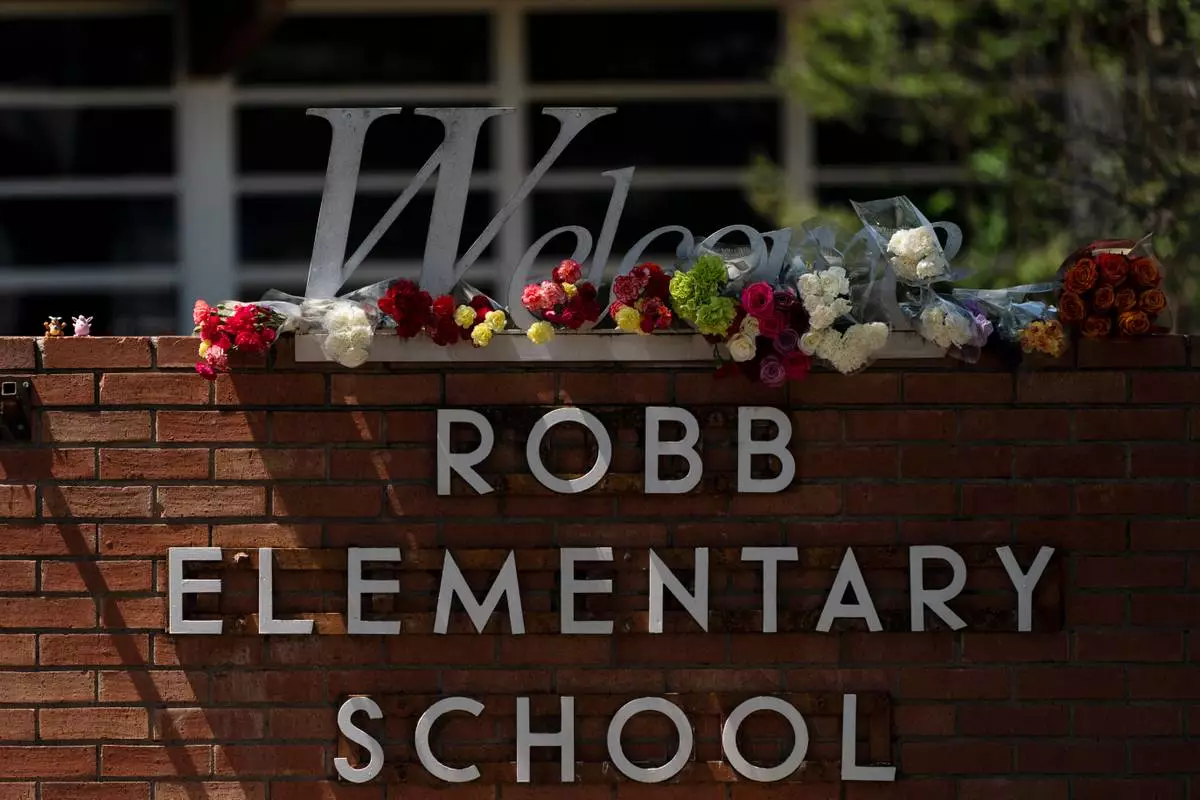

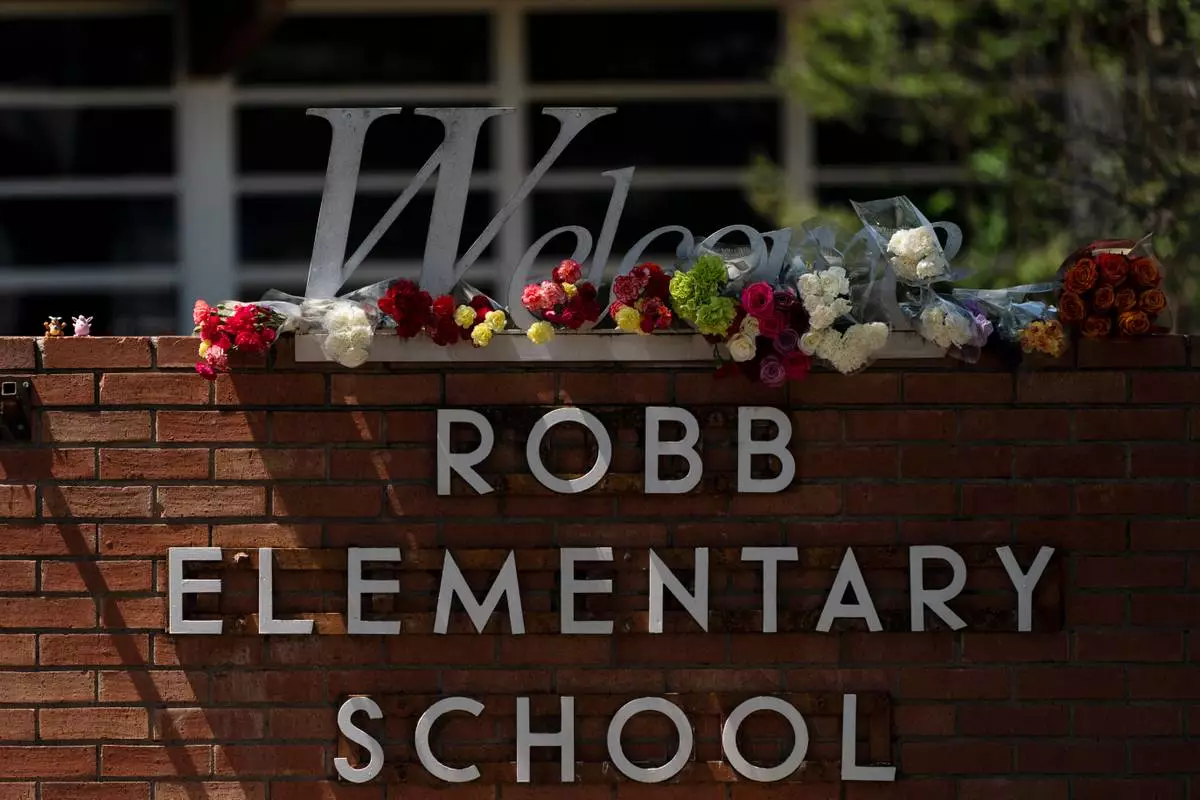

FILE - Crosses with the names of shooting victims are placed outside Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, May 26, 2022. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong, File)

People enter the Nueces County Courthouse in Corpus Christi, Texas, as jury selection continues in the trial for former Uvalde school district police officer Adrian Gonzales, Monday, Jan. 5, 2026. (AP Photo/Eric Gay)

A line forms at the Nueces County Courthouse in Corpus Christi, Texas, as jury selection continues in the trial for former Uvalde school district police officer Adrian Gonzales, Monday, Jan. 5, 2026. (AP Photo/Eric Gay)

FILE - This booking image provided by the Uvalde County, Texas, Sheriff's Office shows Adrian Gonzales, a former police officer for schools in Uvalde, Texas. (Uvalde County Sheriff's Office via AP, File)

FILE - Flowers are placed around a welcome sign outside Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, May 25, 2022, to honor the victims killed in a shooting at the school. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong, File)