LANSING, Mich. (AP) — During Michigan Supreme Court Justice Kyra Harris Bolden's first campaign, a critic told her she wasn't Michelle Obama or Kamala Harris, “but you feel emboldened to run for this office.”

She later named her first child Emerson, so it could be shortened to “Em Bolden.” The word has driven her ever since.

Click to Gallery

Justices of the Michigan Supreme Court enter their court at the Michigan Hall of Justice, Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2024, in Lansing, Mich. (AP Photo/Carlos Osorio)

Michigan Supreme Court Justice Kyra Harris Bolden listens to oral arguments at the Michigan Hall of Justice, Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2024, in Lansing, Mich. (AP Photo/Carlos Osorio)

Justices of the Michigan Supreme Court Megan K. Cavanagh, left, and Kyra Harris Bolden listen to oral arguments at the Michigan Hall of Justice, Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2024, in Lansing, Mich. (AP Photo/Carlos Osorio)

Michigan Supreme Court Justice Kyra Harris Bolden at home, Monday, Dec. 2, 2024, in Farmington, Mich. Justice Bolden is the first Black woman to be elected to the Michigan Supreme Court. (AP Photo/Carlos Osorio)

Michigan Supreme Court Justice Kyra Harris Bolden at home, Monday, Dec. 2, 2024, in Farmington, Mich. Justice Bolden is the first Black woman to be elected to the Michigan Supreme Court. (AP Photo/Carlos Osorio)

Michigan Supreme Court Justice Kyra Harris Bolden listens to oral arguments at the Michigan Hall of Justice, Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2024, in Lansing, Mich. (AP Photo/Carlos Osorio)

Bolden, now 36, won that race, for the statehouse in 2018, and in 2022 she was appointed as the youngest-ever justice, and first Black woman, on Michigan's top court. Voters affirmed Gov. Gretchen Whitmer's choice by electing Bolden to her seat in November.

“It’s been a long journey for me,” Bolden told The Associated Press, one that began generations ago when her great-grandfather was lynched and her family fled the South.

Michigan has a long legacy of electing women to its highest court. When Democratic-backed candidate Kimberly Ann Thomas joins Bolden on the bench in January, five of the seven justices will be women. It is the sixth time a female majority has made up the court, according to the Michigan Supreme Court Historical Society.

But only 41 Black women have ever served on a state supreme court, according to the Brennan Center for Justice, which tracks diversity in the judicial system.

Bolden’s election means that Black people in Michigan — about 14% of the population — still have representation. Across the state line in Ohio, where Justice Melody Stewart had been the first Black woman justice, her reelection loss makes for an all-white court.

In Kentucky, Court of Appeals Judge Pamela Goodwine became the first Black woman elected justice. Kentucky also will have its first female chief justice and, for the first time, a female majority.

It was an act of racial terror that sent Bolden on her path to the court. She didn't know the details until she was nearly a college graduate in psychology and spent some time with her aging maternal great-grandmother, who shared family recipes and history, including what really happened to Jesse Lee Bond.

According to the Equal Justice Initiative, Bond was lynched in 1939 in Arlington, Tennessee, after asking a store owner for a receipt. Bond was fatally shot, castrated and dumped in the Loosahatchie River. Two men were swiftly acquitted in the murder.

Bolden said she is still trying to reconcile with the trauma this caused.

“I wanted families to see justice in a way my family had not seen justice,” she told the AP.

So she took action: earning her degree at Detroit Mercy Law School and working as a defense attorney before serving on the House Judiciary Committee, where she pursued criminal justice reform and domestic violence prevention.

“She believes in justice and believes in fairness for everybody,” said her mother, Cheryl Harris, with pride heavy in her voice. “And to see her in this position — it’s making me tear up right now.”

Goodwine, for her part, said she was inspired as a teenager by the work of Thurgood Marshall, the first Black U.S. Supreme Court Justice. She started as a court stenographer and worked her way up through the four court levels of Kentucky, making history at almost every step along the way.

“It is absolutely essential that our younger generations are able to see someone who looks like them in every position, particularly a position of power,” Goodwine said.

Bolden broke another barrier knocking on doors as the first Michigan Supreme Court candidate to run while pregnant, according to Vote Mama Foundation, a group that tracks mothers running for office.

“There are so many people that don’t know that this is achievable,” Bolden said.

U.S. Rep. Brenda Lawrence, a Michigan Democrat who served in Congress from 2015 through 2022, spent years working to see a Black woman like herself serve as a justice.

“I just sit back, you know, with such pride,” Lawrence said. “She’s a hard worker and she’s what the state needs.”

The Associated Press’ women in the workforce and state government coverage receives financial support from Pivotal Ventures. The AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Justices of the Michigan Supreme Court enter their court at the Michigan Hall of Justice, Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2024, in Lansing, Mich. (AP Photo/Carlos Osorio)

Michigan Supreme Court Justice Kyra Harris Bolden listens to oral arguments at the Michigan Hall of Justice, Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2024, in Lansing, Mich. (AP Photo/Carlos Osorio)

Justices of the Michigan Supreme Court Megan K. Cavanagh, left, and Kyra Harris Bolden listen to oral arguments at the Michigan Hall of Justice, Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2024, in Lansing, Mich. (AP Photo/Carlos Osorio)

Michigan Supreme Court Justice Kyra Harris Bolden at home, Monday, Dec. 2, 2024, in Farmington, Mich. Justice Bolden is the first Black woman to be elected to the Michigan Supreme Court. (AP Photo/Carlos Osorio)

Michigan Supreme Court Justice Kyra Harris Bolden at home, Monday, Dec. 2, 2024, in Farmington, Mich. Justice Bolden is the first Black woman to be elected to the Michigan Supreme Court. (AP Photo/Carlos Osorio)

Michigan Supreme Court Justice Kyra Harris Bolden listens to oral arguments at the Michigan Hall of Justice, Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2024, in Lansing, Mich. (AP Photo/Carlos Osorio)

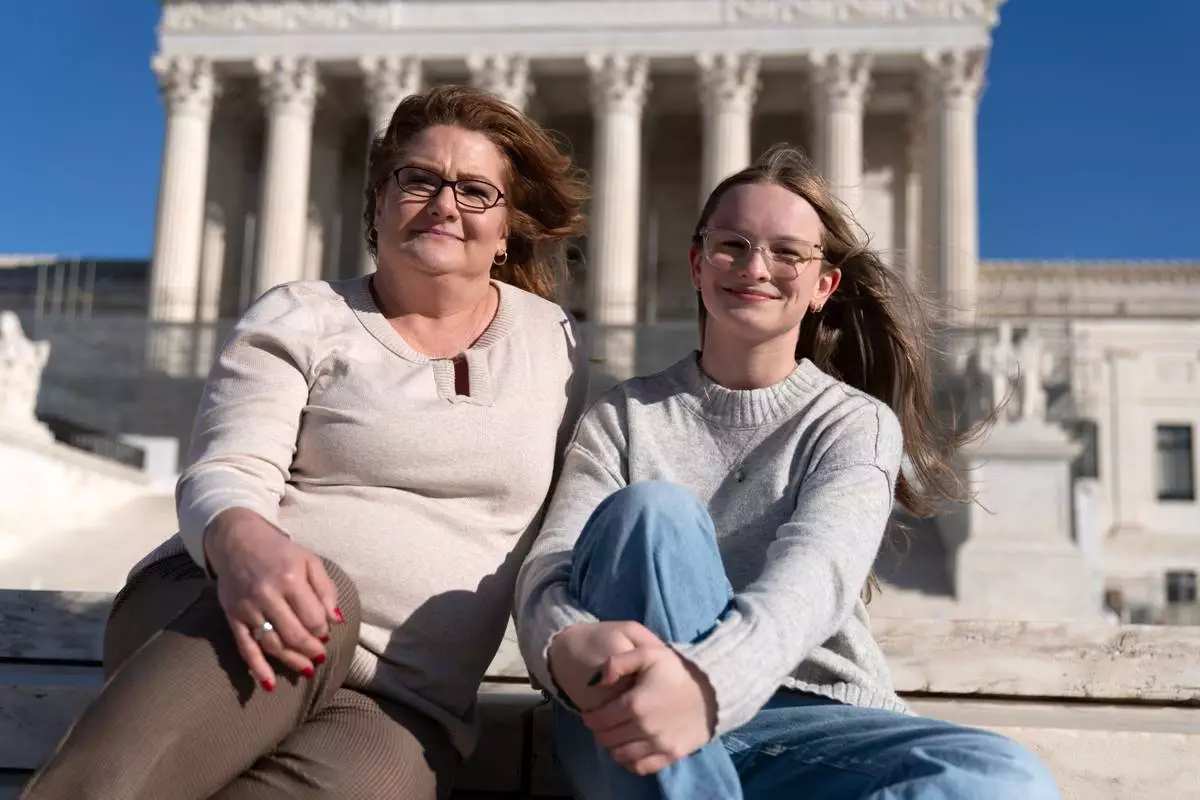

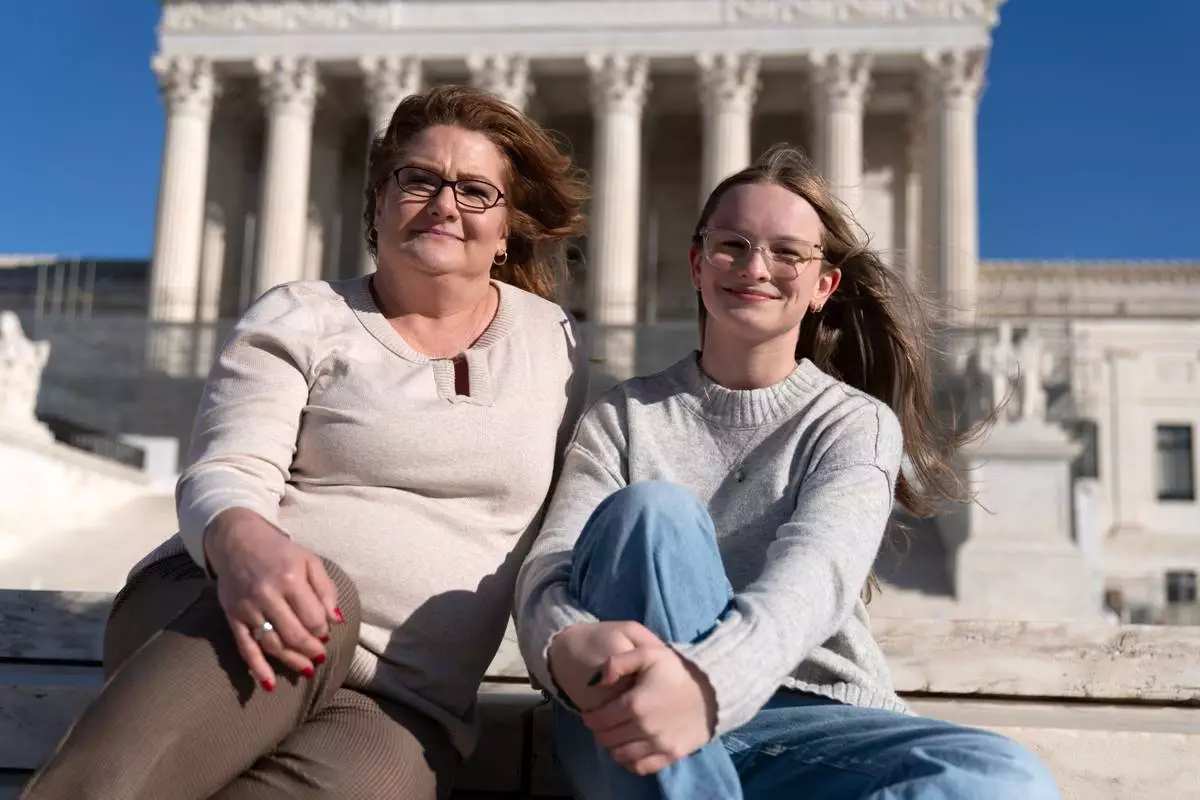

WASHINGTON (AP) — Becky Pepper-Jackson finished third in the discus throw in West Virginia last year though she was in just her first year of high school. Now a 15-year-old sophomore, Pepper-Jackson is aware that her upcoming season could be her last.

West Virginia has banned transgender girls like Pepper-Jackson from competing in girls and women's sports, and is among the more than two dozen states with similar laws. Though the West Virginia law has been blocked by lower courts, the outcome could be different at the conservative-dominated Supreme Court, which has allowed multiple restrictions on transgender people to be enforced in the past year.

The justices are hearing arguments Tuesday in two cases over whether the sports bans violate the Constitution or the landmark federal law known as Title IX that prohibits sex discrimination in education. The second case comes from Idaho, where college student Lindsay Hecox challenged that state's law.

Decisions are expected by early summer.

President Donald Trump's Republican administration has targeted transgender Americans from the first day of his second term, including ousting transgender people from the military and declaring that gender is immutable and determined at birth.

Pepper-Jackson has become the face of the nationwide battle over the participation of transgender girls in athletics that has played out at both the state and federal levels as Republicans have leveraged the issue as a fight for athletic fairness for women and girls.

“I think it’s something that needs to be done,” Pepper-Jackson said in an interview with The Associated Press that was conducted over Zoom. “It’s something I’m here to do because ... this is important to me. I know it’s important to other people. So, like, I’m here for it.”

She sat alongside her mother, Heather Jackson, on a sofa in their home just outside Bridgeport, a rural West Virginia community about 40 miles southwest of Morgantown, to talk about a legal fight that began when she was a middle schooler who finished near the back of the pack in cross-country races.

Pepper-Jackson has grown into a competitive discus and shot put thrower. In addition to the bronze medal in the discus, she finished eighth among shot putters.

She attributes her success to hard work, practicing at school and in her backyard, and lifting weights. Pepper-Jackson has been taking puberty-blocking medication and has publicly identified as a girl since she was in the third grade, though the Supreme Court's decision in June upholding state bans on gender-affirming medical treatment for minors has forced her to go out of state for care.

Her very improvement as an athlete has been cited as a reason she should not be allowed to compete against girls.

“There are immutable physical and biological characteristic differences between men and women that make men bigger, stronger, and faster than women. And if we allow biological males to play sports against biological females, those differences will erode the ability and the places for women in these sports which we have fought so hard for over the last 50 years,” West Virginia's attorney general, JB McCuskey, said in an AP interview. McCuskey said he is not aware of any other transgender athlete in the state who has competed or is trying to compete in girls or women’s sports.

Despite the small numbers of transgender athletes, the issue has taken on outsize importance. The NCAA and the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committees banned transgender women from women's sports after Trump signed an executive order aimed at barring their participation.

The public generally is supportive of the limits. An Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research poll conducted in October 2025 found that about 6 in 10 U.S. adults “strongly” or “somewhat” favored requiring transgender children and teenagers to only compete on sports teams that match the sex they were assigned at birth, not the gender they identify with, while about 2 in 10 were “strongly” or “somewhat” opposed and about one-quarter did not have an opinion.

About 2.1 million adults, or 0.8%, and 724,000 people age 13 to 17, or 3.3%, identify as transgender in the U.S., according to the Williams Institute at the UCLA School of Law.

Those allied with the administration on the issue paint it in broader terms than just sports, pointing to state laws, Trump administration policies and court rulings against transgender people.

"I think there are cultural, political, legal headwinds all supporting this notion that it’s just a lie that a man can be a woman," said John Bursch, a lawyer with the conservative Christian law firm Alliance Defending Freedom that has led the legal campaign against transgender people. “And if we want a society that respects women and girls, then we need to come to terms with that truth. And the sooner that we do that, the better it will be for women everywhere, whether that be in high school sports teams, high school locker rooms and showers, abused women’s shelters, women’s prisons.”

But Heather Jackson offered different terms to describe the effort to keep her daughter off West Virginia's playing fields.

“Hatred. It’s nothing but hatred,” she said. "This community is the community du jour. We have a long history of isolating marginalized parts of the community.”

Pepper-Jackson has seen some of the uglier side of the debate on display, including when a competitor wore a T-shirt at the championship meet that said, “Men Don't Belong in Women's Sports.”

“I wish these people would educate themselves. Just so they would know that I’m just there to have a good time. That’s it. But it just, it hurts sometimes, like, it gets to me sometimes, but I try to brush it off,” she said.

One schoolmate, identified as A.C. in court papers, said Pepper-Jackson has herself used graphic language in sexually bullying her teammates.

Asked whether she said any of what is alleged, Pepper-Jackson said, “I did not. And the school ruled that there was no evidence to prove that it was true.”

The legal fight will turn on whether the Constitution's equal protection clause or the Title IX anti-discrimination law protects transgender people.

The court ruled in 2020 that workplace discrimination against transgender people is sex discrimination, but refused to extend the logic of that decision to the case over health care for transgender minors.

The court has been deluged by dueling legal briefs from Republican- and Democratic-led states, members of Congress, athletes, doctors, scientists and scholars.

The outcome also could influence separate legal efforts seeking to bar transgender athletes in states that have continued to allow them to compete.

If Pepper-Jackson is forced to stop competing, she said she will still be able to lift weights and continue playing trumpet in the school concert and jazz bands.

“It will hurt a lot, and I know it will, but that’s what I’ll have to do,” she said.

Heather Jackson, left, and Becky Pepper-Jackson pose for a photograph outside of the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington, Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026. (AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana)

Heather Jackson, left, and Becky Pepper-Jackson pose for a photograph outside of the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington, Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026. (AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana)

Becky Pepper-Jackson poses for a photograph outside of the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington, Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026. (AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana)

The Supreme Court stands is Washington, Friday, Jan. 9, 2026. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

FILE - Protestors hold signs during a rally at the state capitol in Charleston, W.Va., on March 9, 2023. (AP Photo/Chris Jackson, file)