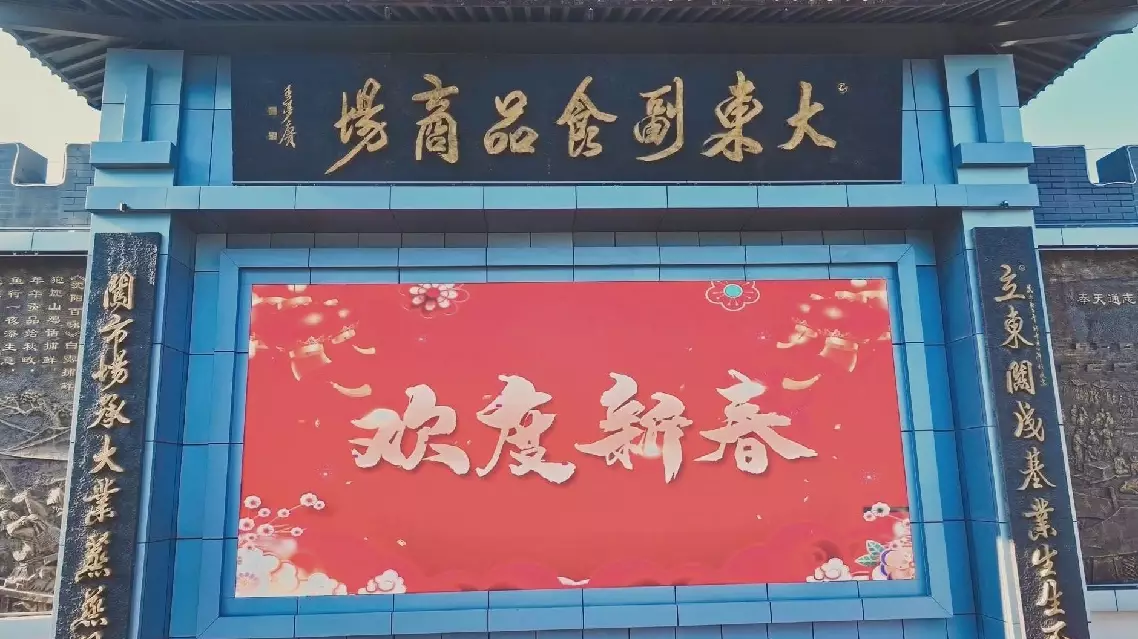

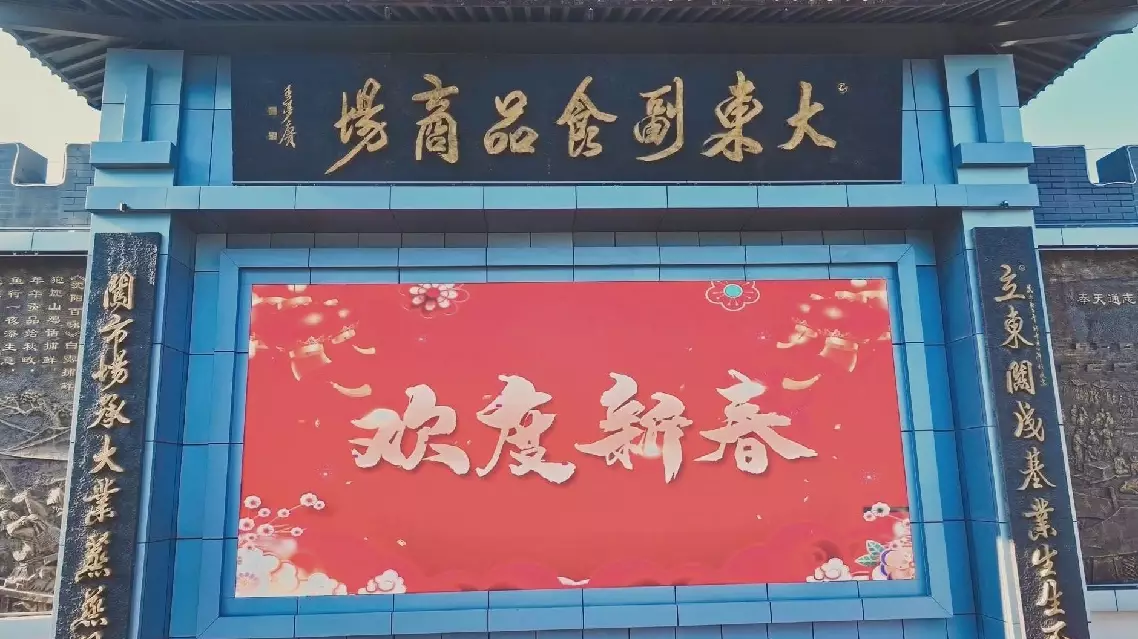

Chinese President Xi Jinping on Thursday visited a food market in Shenyang City of the northeastern Liaoning Province to learn about market supply, daily necessities assurance for residents, and improvements in convenient and people-beneficial services during the upcoming Spring Festival holiday.

Xi made the trip shortly before the Spring Festival, the most important festival for the Chinese people, which falls on Jan 29 this year.

Shenyang Dadong Nonstaple Food Market has a nearly 200-year history. It began operating under public-private partnership in 1956, and in 1984 it was renamed "Dadong Nonstaple Food Market." It is a company under the Shenyang Nonstaple Foods Group, a municipal state-owned enterprise.

The market offers over 7,000 types of products and more than 500 specialty items, including local delicacies such as Goubangzi smoked chicken, Eight Banners handmade sausages, and Sixi meatballs.

Currently, the market consistently maintains stable price and supply, with an average daily customer flow of 20,000 people, ensuring food supply for the residents of Shenyang. Boasting reliable quality and honest pricing, the market has achieved significant economic and social benefits.

Xi visits food market in Shenyang City ahead of Spring Festival

Li Yuhua, a farmer-turned forest ranger from a mountainous village in Dulongjiang Town, southwest China's Yunnan Province, has spent nine years protecting the forests in her hometown while helping local people increasing their incomes.

Li's family was once a registered impoverished household, relying mainly on corn farming for living. Things began to change for her family in 2016 when China launched a policy allowing registered impoverished population to work as ecological forest rangers, and Li became one of the first ecological forest rangers in the town.

"When I first began to work as a forest ranger, it was hard for me even to climb mountains, let alone climb rocks and cross rivers. But I told myself that since the country gave me this opportunity, I must do it well. I worked hard to improve my physical fitness and learn new skills, always actively taking the missions of patrolling mountains," said Li.

As Li often wears a colorful, vibrantly striped "Dulong blanket," a traditional clothing of the Dulong ethnic group, the villagers call her the "rainbow ranger."

"I think the name 'Rainbow Ranger' is beautiful. It makes me feel like a rainbow for us women of Dulong ethnic group guarding our homeland," Li said.

Dulong is a mountain-dwelling ethnic group in southwest China. It is one of the least populous of China's 56 ethnic groups, and the people were known for "direct transition" from primitive life to the modern socialist society at the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949.

Most Dulong people live in Dulongjiang Town, where an inhospitable mountainous terrain used to thwart the place's development for decades. The town remained to be one of the poorest areas in Yunnan Province and even in the entire country. Thanks to government inputs and the development of industries with local features, the Dulong people have been experiencing remarkable life changes. In 2018, the Dulong ethnic group shook off poverty as a whole.

Beyond safeguarding forests, Li took the lead in developing non-timber forest-based economy in the town, guiding local residents to grow plants like Chinese black cardamom and wild-simulated lingzhi mushrooms as well as raising cattle and bees.

In 2025, the total output value of the town's non-timber forest-based economy reached nearly 30 million yuan (around 4.3 million U.S. dollars), with the annual average income of 43 households increasing by more than 20,000 yuan (around 2,900 U.S. dollars) each.

Li also established a cooperative for Dulong blanket making, attracting more than 170 women to learn traditional weaving techniques. They have developed 12 types of cultural and creative products, including shawls and scarves, and sold them worldwide through livestreaming, generating wealth for themselves.

"In the past, we only wove blankets for our own use. Now she teaches us to make the cultural and creative products and sell them. Last year, I earned more than 4,000 yuan (around 580 U.S. dollars) from weaving. I spent the money on my children's school fees and new appliances for my house," said Mu Jianying, member of the cooperative.

Li's dedication to both forestry and rural revitalization has earned her widespread recognition. In 2024, she was honored as model of ethnic solidarity and progress and received the title certificate from President Xi Jinping. She was also awarded the title of National March 8 Red-Banner Pacesetter, the highest honor presented by the All-China Women's Federation to the country's outstanding women, ahead of the International Women's Day observed on March 8.

Li said her achievements are the result of collective efforts.

"I often think that one person's strength is very limited, but the strength of a group is great. There are 195 ecological forest rangers like me protecting this land in the Dulongjiang Grand Canyon," she said.

As a female forest ranger, Li shared a message for women ahead of the International Women's Day.

"To mark the International Women's Day, I want to say to all my sisters: No matter what position we are in, as long as we are willing to endure hardship and work hard, we will surely weave our own rainbow," she said.

Forest ranger dedicated to guarding green mountains in Yunnan

Forest ranger dedicated to guarding green mountains in Yunnan