NEW YORK (AP) — Google's online calendar has removed default references for a handful of holidays and cultural events — with users noticing that mentions of Pride and Black History Month, as well as other observances, no longer appear in their desktop and mobile applications.

The omissions gained attention online over the last week, particularly around upcoming events that are no longer automatically listed. But Google says it made the change midway through last year.

The California-based tech giant said it manually added "a broader set of cultural moments in a wide number of countries” for several years, supplementing public holidays and national observances from timeanddate.com that have been used to populate Google Calendar for over a decade. Still, the company added, it received feedback about some other missing events and countries.

“Maintaining hundreds of moments manually and consistently globally wasn’t scalable or sustainable,” Google said in a statement sent to The Associated Press. "So in mid-2024 we returned to showing only public holidays and national observances from timeanddate.com globally, while allowing users to manually add other important moments.”

Google did not provide a full list of the cultural events it added prior to last year's change — and therefore no longer appear by default today.

But social media users and product experts posting to online community boards have pointed to several holidays and cultural observances that they're not seeing anymore. In addition to the first days of Pride Month and Black History Month, that includes the start of Indigenous Peoples Month and Hispanic Heritage Month, as well as Holocaust Remembrance Day. The Verge first reported on some of these omissions last week.

Norway-based Time and Date AS, which operates timeanddate.com, did not immediately respond to requests for comment Tuesday. The website shows numerous country-by-country lists of holidays and observances from around the world — some of which include cultural awareness events like Pride and Black History Month — but those specific to public holidays are more limited.

Separate from this Calendar shift, Google has also gained attention over its more recent decision to change the names of the Gulf of Mexico and Denali on Google Maps — following orders from President Donald Trump to rename the body of water bordering the U.S., Mexico and Cuba the Gulf of America, as well as revert the title of America’s highest mountain peak back to Mt. McKinley.

“We have a longstanding practice of applying name changes when they have been updated in official government sources,” Google said last month. The company added that its maps will reflect any updates to the Geographic Names Information System, a database of more than 1 million geographic features in the U.S.

Google confirmed Monday that the Gulf of America name had gone into effect. Google Maps users in the U.S. now only see the Gulf of America name, whereas those in other countries see both names. Denali, however, still appears on both Google Maps and the GNIS.

And the new names on Google Maps aren't the only change the company has made following recent actions from the Trump administration. Last week, Google outlined plans to scrap some of its diversity hiring targets — joining a growing list of U.S. companies that have abandoned or scaled back their diversity, equity and inclusion programs. Google's move notably came in the wake of an executive order aimed, in part, at pressuring government contractors to end DEI initiatives. As a federal contractor, Google said it was evaluating required changes.

By Tuesday, both Apple and Microsoft’s Bing made the switch from Gulf of Mexico to Gulf of America on their maps.

FILE - A woman walks by a giant screen with a logo at an event at the Paris Google Lab on the sidelines of the AI Action Summit in Paris, Feb. 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Thibault Camus, file)

When Indiana adopted new U.S. House districts four years ago, Republican legislative leaders lauded them as “fair maps” that reflected the state's communities.

But when Gov. Mike Braun recently tried to redraw the lines to help Republicans gain more power, he implored lawmakers to "vote for fair maps.”

What changed? The definition of “fair.”

As states undertake mid-decade redistricting instigated by President Donald Trump, Republicans and Democrats are using a tit-for-tat definition of fairness to justify districts that split communities in an attempt to send politically lopsided delegations to Congress. It is fair, they argue, because other states have done the same. And it is necessary, they claim, to maintain a partisan balance in the House of Representatives that resembles the national political divide.

This new vision for drawing congressional maps is creating a winner-take-all scenario that treats the House, traditionally a more diverse patchwork of politicians, like the Senate, where members reflect a state's majority party. The result could be reduced power for minority communities, less attention to certain issues and fewer distinct voices heard in Washington.

Although Indiana state senators rejected a new map backed by Trump and Braun that could have helped Republicans win all nine of the state’s congressional seats, districts have already been redrawn in Texas, California, Missouri, North Carolina and Ohio. Other states could consider changes before the 2026 midterms that will determine control of Congress.

“It’s a fundamental undermining of a key democratic condition,” said Wayne Fields, a retired English professor from Washington University in St. Louis who is an expert on political rhetoric.

“The House is supposed to represent the people,” Fields added. “We gain an awful lot by having particular parts of the population heard.”

Under the Constitution, the Senate has two members from each state. The House has 435 seats divided among states based on population, with each state guaranteed at least one representative. In the current Congress, California has the most at 52, followed by Texas with 38.

Because senators are elected statewide, they are almost always political pairs of one party or another. Pennsylvania and Wisconsin are the only states now with both a Democrat and Republican in the Senate. Maine and Vermont each have one independent and one senator affiliated with a political party.

By contrast, most states elect a mixture of Democrats and Republicans to the House. That is because House districts, with an average of 761,000 residents, based on the 2020 census, are more likely to reflect the varying partisan preferences of urban or rural voters, as well as different racial, ethnic and economic groups.

This year's redistricting is diminishing those locally unique districts.

In California, voters in several rural counties that backed Trump were separated from similar rural areas and attached to a reshaped congressional district containing liberal coastal communities. In Missouri, Democratic-leaning voters in Kansas City were split from one main congressional district into three, with each revised district stretching deep into rural Republican areas.

Some residents complained their voices are getting drowned out. But Govs. Gavin Newsom, D-Calif., and Mike Kehoe, R-Mo., defended the gerrymandering as a means of countering other states and amplifying the voices of those aligned with the state's majority.

Indiana's delegation in the U.S. House consists of seven Republicans and two Democrats — one representing Indianapolis and the other a suburban Chicago district in the state's northwestern corner.

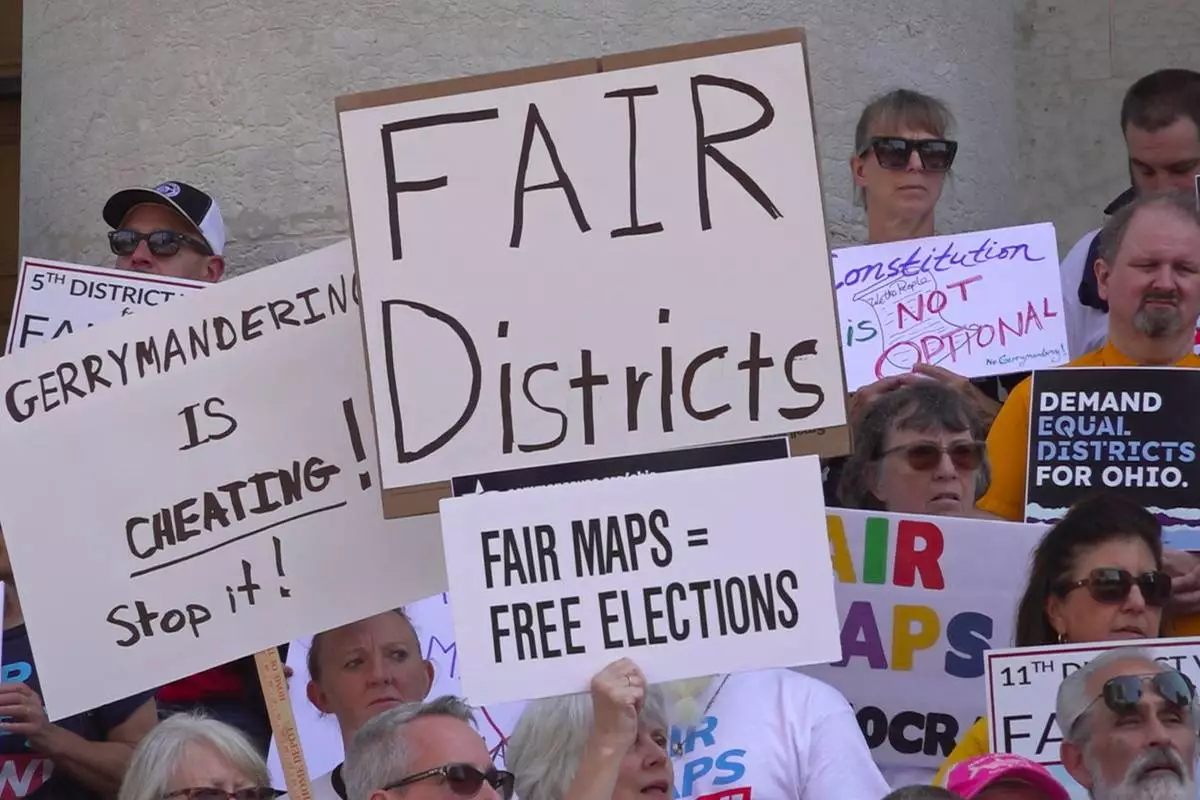

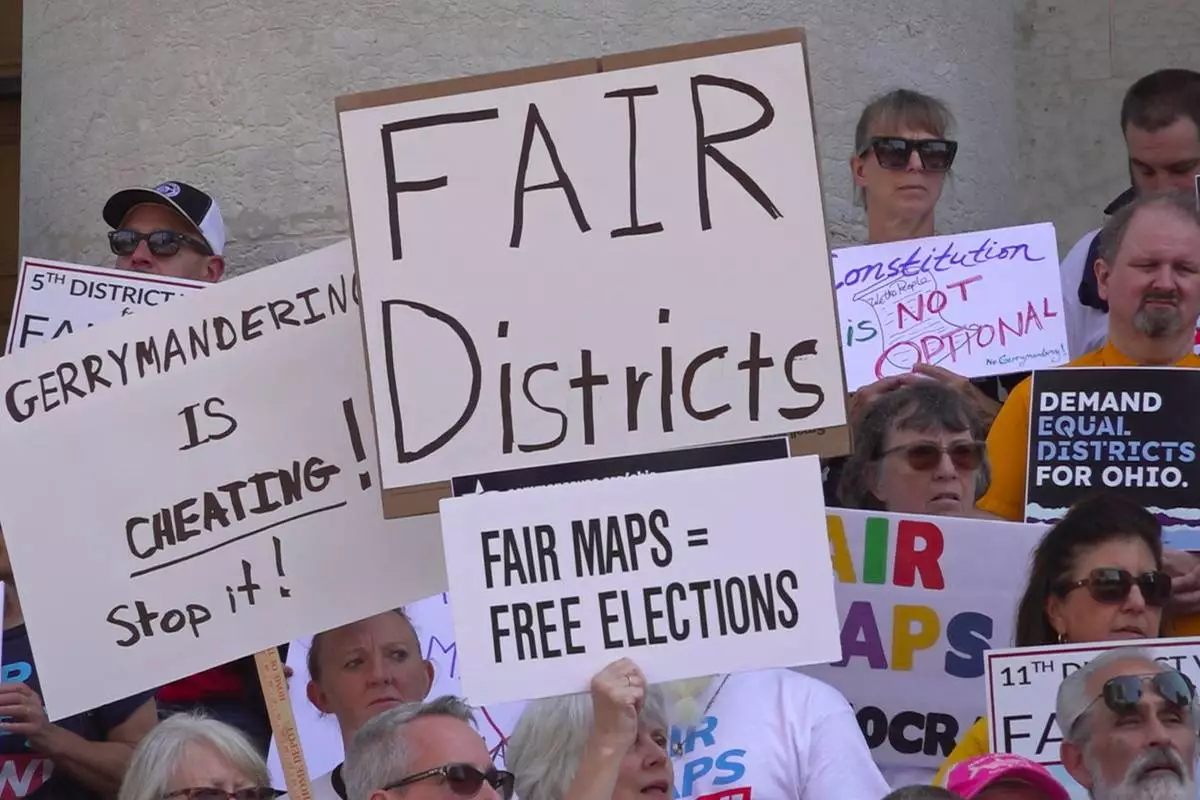

Dueling definitions of fairness were on display at the Indiana Capitol as lawmakers considered a Trump-backed redistricting plan that would have split Indianapolis among four Republican-leaning districts and merged the Chicago suburbs with rural Republican areas. Opponents walked the halls in protest, carrying signs such as “I stand for fair maps!”

Ethan Hatcher, a talk radio host who said he votes for Republicans and Libertarians, denounced the redistricting plan as “a blatant power grab" that "compromises the principles of our Founding Fathers" by fracturing Democratic strongholds to dilute the voices of urban voters.

“It’s a calculated assault on fair representation," Hatcher told a state Senate committee.

But others asserted it would be fair for Indiana Republicans to hold all of those House seats, because Trump won the “solidly Republican state” by nearly three-fifths of the vote.

“Our current 7-2 congressional delegation doesn’t fully capture that strength,” resident Tracy Kissel said at a committee hearing. "We can create fairer, more competitive districts that align with how Hoosiers vote.”

When senators defeated a map designed to deliver a 9-0 congressional delegation for Republicans, Braun bemoaned that they had missed an “opportunity to protect Hoosiers with fair maps.”

By some national measurements, the U.S. House already is politically fair. The 220-215 majority that Republicans won over Democrats in the 2024 elections almost perfectly aligns with the share of the vote the two parties received in districts across the country, according to an Associated Press analysis.

But that overall balance belies an imbalance that exists in many states. Even before this year's redistricting, the number of states with congressional districts tilted toward one party or another was higher than at any point in at least a decade, the AP analysis found.

The partisan divisions have contributed to a “cutthroat political environment” that “drives the parties to extreme measures," said Kent Syler, a political science professor at Middle Tennessee State University. He noted that Republicans hold 88% of congressional seats in Tennessee, and Democrats have an equivalent in Maryland.

“Fairer redistricting would give people more of a feeling that they have a voice," Syler said.

Rebekah Caruthers, who leads the Fair Elections Center, a nonprofit voting rights group, said there should be compact districts that allow communities of interest to elect the representatives of their choice, regardless of how that affects the national political balance. Gerrymandering districts to be dominated by a single party results in “an unfair disenfranchisement" of some voters, she said.

“Ultimately, this isn’t going to be good for democracy," Caruthers said. "We need some type of détente.”

A protester celebrates as they walk outside the Indiana Senate Chamber after a bill to redistrict the state's congressional map was defeated, Thursday, Dec. 11, 2025, at the Statehouse in Indianapolis. (AP Photo/Michael Conroy)

FILE - This photo taken from video shows organizers rallying outside of the Ohio Statehouse to protest gerrymandering and advocate for lawmakers to draw fair maps in Columbus, Ohio, Sept. 17, 2025. (AP Photo/Patrick Aftoora-Orsagos, File)

Opponents of Missouri's Republican-backed congressional redistricting plan display a banner in protest at the State Capitol in Jefferson City, Missouri, Sept. 10, 2025. (AP Photo/David A. Lieb)