MEXICO CITY (AP) — Legend has it the axolotl was not always an amphibian. Long before it became Mexico’s most beloved salamander and efforts to prevent its extinction flourished, it was a sneaky god.

“It’s an interesting little animal,” said Yanet Cruz, head of the Chinampaxóchitl Museum in Mexico City.

Its exhibitions focus on axolotl and chinampas, the pre-Hispanic agricultural systems resembling floating gardens that still function in Xochimilco, a neighborhood on Mexico City's outskirts famed for its canals.

“Despite there being many varieties, the axolotl from the area is a symbol of identity for the native people,” said Cruz, who participated in activities hosted at the museum to celebrate “Axolotl Day” in early February.

While there are no official estimates of the current axolotl population, the species Ambystoma mexicanum — endemic of central Mexico— has been catalogued as “critically endangered” by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species since 2019. And though biologists, historians and officials have led efforts to save the species and its habitat from extinction, a parallel, unexpected preservation phenomenon has emerged.

Axolotl attracted international attention after Minecraft added them to its game in 2021 and Mexicans went crazy about them that same year, following the Central Bank's initiative to print it on the 50-peso bill. “That’s when the ‘axolotlmania’ thrived,” Cruz said.

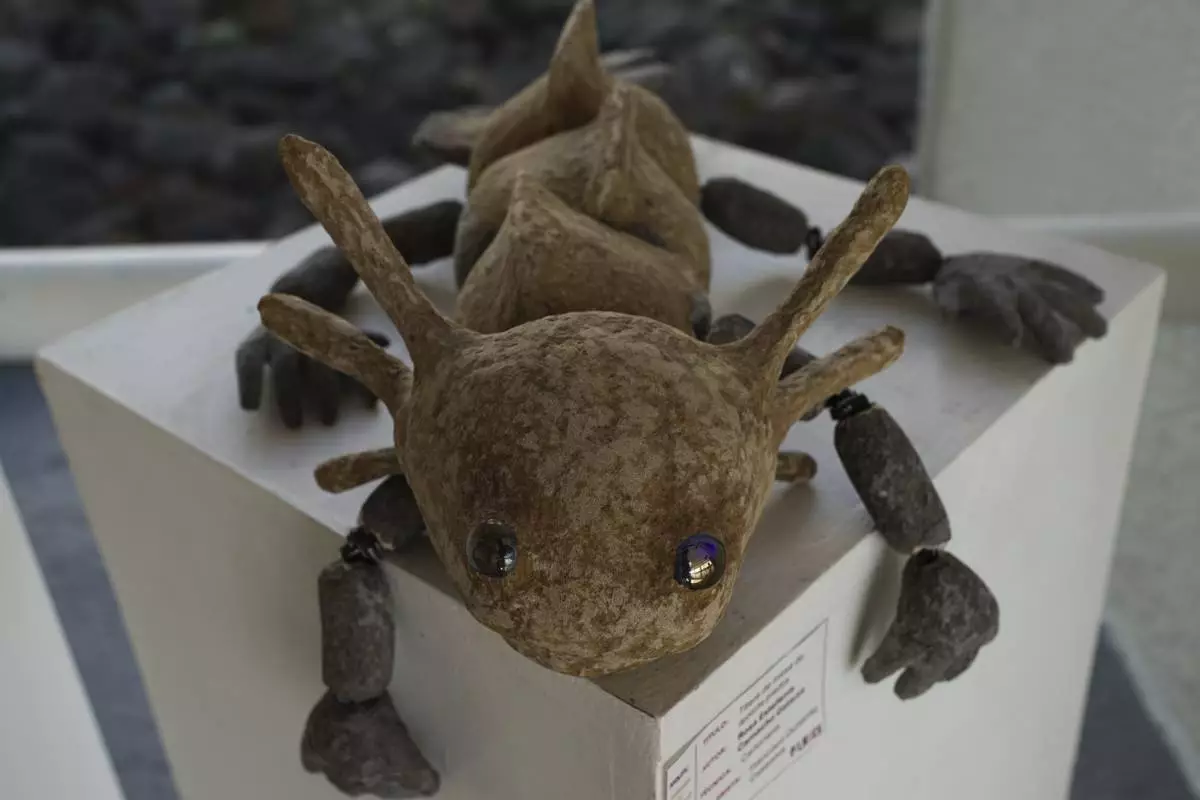

All over Mexico, the peculiar, dragon-like amphibian can be spotted in murals, crafts and socks. Selected bakeries have caused a sensation with its axolotl-like bites. Even a local brewery — “Ajolote” in Spanish — took its name from the salamander to honor Mexican traditions.

Before the Spaniards conquered Mexico-Tenochtitlan in the 16th century, axolotl may not have had archeological representations as did Tláloc — god of rain in the Aztec worldview — or Coyolxauhqui — its lunar goddess — but it did appear in ancient Mesoamerican documents.

In the Nahua myth of the Fifth Sun, pre-Hispanic god Nanahuatzin threw himself into a fire, reemerged as the sun and commanded fellow gods to replicate his sacrifice to bring movement to the world. All complied but Xólotl, a deity associated with the evening star, who fled.

“He was hunted down and killed,” said Arturo Montero, archeologist of the National Commission of Protected Natural Areas. “And from his death came a creature: axolotl.”

According to Montero, the myth implies that, after a god’s passing, its essence gets imprisoned in a mundane creature, subject to the cycles of life and death. Axolotl then carries within itself the Xolotl deity, and when the animal dies and its divine substance transits to the underworld, it later resurfaces to the earth and a new axolotl is born.

“Axolotl is the twin of maize, agave and water,” Montero said.

Current fascination toward axolotl and its rise to sacred status in pre-Hispanic times is hardly a coincidence. It was most likely sparked by its exceptional biological features, Montero said.

Through the glass of a fish tank, where academic institutions preserve them and hatcheries put them up for sale, axolotl are hard to spot. Their skin is usually dark to mimic stones — though an albino, pinkish variety can be bred — and they can stay still for hours, buried in the muddy ground of their natural habitats or barely moving at the bottom of their tanks in captivity.

Aside from their lungs, they breathe through their gills and skin, which allows them to adapt to its aquatic environment. And they can regenerate parts of its heart, spinal cord and brain.

“This species is quite peculiar,” said biologist Arturo Vergara, who supervises axolotl preservation efforts in various institutions and cares after specimens for sale at a hatchery in Mexico City.

Depending on the species, color and size, Axolotl’s prices at Ambystomania — where Vergara works — start at 200 pesos ($10 US). Specimens are available for sale when they reach four inches in length and are easy pets to look after, Vergara said.

“While they regularly have a 15-years life span (in captivity), we’ve had animals that have lived up to 20,” he added. “They are very long-lived, though in their natural habitat they probably wouldn’t last more than three or four years.”

The species on display at the museum — one of 17 known varieties in Mexico — is endemic to lakes and canals that are currently polluted. A healthy population of axolotl would likely struggle to feed or reproduce.

“Just imagine the bottom of a canal in areas like Xochimilco, Tlahuac, Chalco, where there’s an enormous quantity of microbes,” Vergara said.

Under ideal conditions, an axolotl could heal itself from snake or heron biting and survive the dry season buried in the mud. But a proper aquatic environment is needed for that to happen.

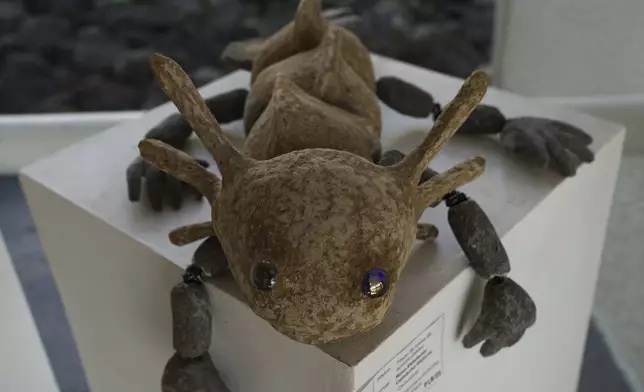

“Efforts to preserve axolotl go hand in hand with preserving the chinampas,” Cruz said at the museum, next to a display featuring salamander-shaped dolls. “We work closely with the community to convince them that this is an important space.”

Chinampas are not only where axolotl lay its eggs, but areas where pre-Hispanic communities grew maize, chili, beans and zucchini, and some of Xochimilco’s current population grow vegetables despite environmental threats.

“Many chinampas are dry and don’t produce food anymore,” Cruz said. “And where some chinampas used to be, one can now see soccer camps.”

For her, like for Vergara, preserving axolotl is not an end, but a means for saving the place where the amphibian came to be.

“This great system (chinampas) is all that’s left from the lake city of Mexico-Tenochtitlan, so I always tell our visitors that Xochimilco is a living archeological zone,” Cruz said. “If we, as citizens, don’t take care of what’s ours, it will be lost.”

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

An axolotl swims around in an aquarium at a museum in Xochimilco Ecological Park, in Mexico City, Tuesday, Feb. 11, 2025. (AP Photo/Marco Ugarte)

Trees surround a lake at Xochimilco Ecological Park, in Mexico City, Tuesday, Feb. 11, 2025. (AP Photo/Marco Ugarte)

A figure of an axolotl sits on display at a museum in Xochimilco Ecological Park, in Mexico City, Tuesday, Feb. 11, 2025. (AP Photo/Marco Ugarte)

A woman holds an axolotl during a media presentation in Xochimilco, a borough of Mexico City, Wednesday, Feb. 16, 2022. (AP Photo/Marco Ugarte)

A figure of an axolotl sits on display at a museum in Xochimilco Ecological Park, in Mexico City, Tuesday, Feb. 11, 2025. (AP Photo/Marco Ugarte)

FILE - Manuel Rodriguez sits atop a canoe shaped like an axolotl during its symbolic release in the canals of Xochimilco, a borough of Mexico City, Feb. 16, 2022. (AP Photo/Marco Ugarte, File)

Axolotls scurry around during a media presentation before their release into the canals of Xochimilco, a borough of Mexico City, Wednesday, Feb. 16, 2022. (AP Photo/Marco Ugarte)

FILE - Ancestral floating gardens are visible next to new soccer fields on Xochimilco Lake in Mexico City, Oct. 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Felix Marquez, File)

An axolotl swims around in an aquarium at a museum in Xochimilco Ecological Park, in Mexico City, Tuesday, Feb. 11, 2025. (AP Photo/Marco Ugarte)