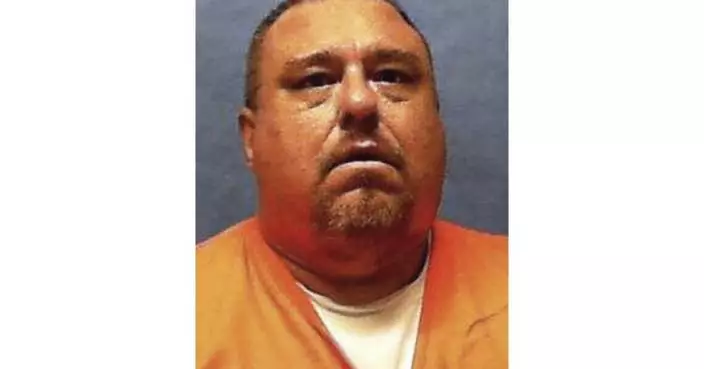

WASHINGTON (AP) — A federal judge on Wednesday said he has found probable cause to hold the Trump administration in criminal contempt of court and warned he could seek officials' prosecution for violating his orders last month to turn around planes carrying deportees to an El Salvador prison.

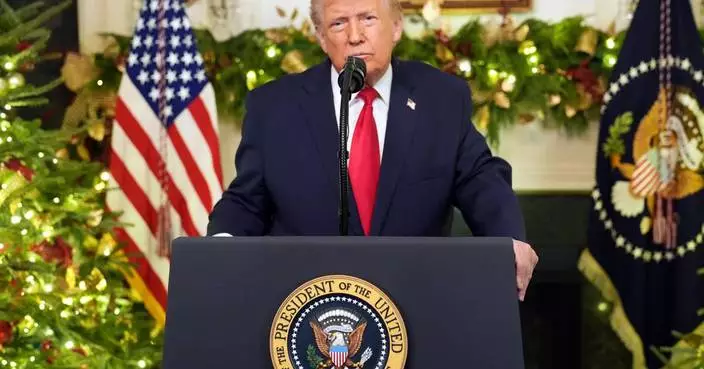

The ruling from U.S District Judge James E. Boasberg, whom President Donald Trump has said should be impeached, marks a dramatic battle between the judicial and executive branches of government over the president’s powers to carry out key White House priorities.

Boasberg accused administration officials of rushing deportees out of the country under the Alien Enemies Act last month before they could challenge their removal in court, and then willfully disregarding his order that planes already in the air should return to the United States.

The judge said he could hold hearings and potentially refer the matter for prosecution if the administration does not act to remedy the violation. If Trump's Justice Department leadership declines to prosecute the matter, Boasberg said he will appoint another attorney to do so.

“The Constitution does not tolerate willful disobedience of judicial orders — especially by officials of a coordinate branch who have sworn an oath to uphold it," wrote Boasberg, the chief judge of Washington's federal court.

The administration said it would appeal.

“The President is 100% committed to ensuring that terrorists and criminal illegal migrants are no longer a threat to Americans and their communities across the country,” White House communications director Steven Cheung wrote in a post on X.

The case has become one of the most contentious amid a slew of legal battles being waged against the Republican administration that has put the White House on a collision course with the federal courts.

Administration officials have repeatedly criticized judges for reigning in the president's actions, accusing the courts of improperly impinging on his executive powers. Trump and his allies have called for impeaching Boasberg, prompting a rare statement from Chief Justice John Roberts, who said “impeachment is not an appropriate response to disagreement concerning a judicial decision.”

Boasberg wrote that the government’s “conduct betrayed a desire to outrun the equitable reach of the Judiciary.”

Boasberg said the government could avoid contempt proceedings if it takes custody of the deportees, who were sent to the El Salvador prison in violation of his order, so they have a chance to challenge their removal. It was not clear how that would work because the judge said the government "would not need to release any of those individuals, nor would it need to transport them back to the homeland.”

The judge did not say which official or officials could be held in contempt. He is giving the government until April 23 to explain the steps it has taken to remedy the violation, or instead identify the individual or people who made the decision not to turn the planes around.

In a separate case, the administration has acknowledged mistakenly deporting Kilmar Abrego Garcia to the El Salvador prison, but does not intend to return him to the U.S. despite a Supreme Court ruling that the administration must “facilitate” his release. The judge in that case has said she is determining whether to undertake contempt proceedings, saying officials “appear to have done nothing to aid in Abrego Garcia’s release from custody and return to the United States.”

Boasberg, who was nominated for the federal bench by Democratic President Barack Obama, had ordered the administration last month not to deport anyone in its custody under the Alien Enemies Act after Trump invoked the 1798 wartime law over what he claimed was an invasion by the Venezuelan gang Tren de Aragua.

When Boasberg was told there were already planes in the air headed to El Salvador, which has agreed to house deported migrants in a notorious prison, the judge said the aircraft needed to be returned to the United States. But hours later, El Salvador’s president, Nayib Bukele, announced that the deportees had arrived in his country. In a social media post, he said, “Oopsie...too late” above an article referencing Boasberg’s order.

The administration has argued it did not violate any orders, noted the judge did not include the turnaround directive in his written order and said the planes had already left the U.S. by the time that order came down.

The Supreme Court earlier this month vacated Boasberg's temporary order blocking the deportations under the Alien Enemies Act, but said the immigrants must be given a chance to fight their removals before they are deported. The conservative majority said the legal challenges must take place in Texas, instead of a Washington courtroom.

Boasberg wrote that even though the Supreme Court found his order “suffered from a legal defect,” that “does not excuse the Government’s violation.” The judge added that the government appeared to have "defied the Court's order deliberately and gleefully,” noting that Secretary of State Marco Rubio retweeted the post from Bukele after the planes landed in El Salvador despite the judge's order.

"The Court does not reach such conclusion lightly or hastily; indeed, it has given Defendants ample opportunity to rectify or explain their actions. None of their responses has been satisfactory," Boasberg wrote.

Associated Press writer Mark Sherman contributed to this report.

FILE - In this photo provided by El Salvador's presidential press office, a prison guard transfers deportees from the U.S., alleged to be Venezuelan gang members, to the Terrorism Confinement Center in Tecoluca, El Salvador, March 16, 2025. (El Salvador presidential press office via AP, File)

FILE - A mega-prison known as Detention Center Against Terrorism (CECOT) stands in Tecoluca, El Salvador, March 5, 2023. (AP Photo/Salvador Melendez, File)

FILE - U.S. District Judge James Boasberg, chief judge of the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, stands for a portrait at E. Barrett Prettyman Federal Courthouse in Washington, March 16, 2023. (Carolyn Van Houten/The Washington Post via AP, File)

MBERA, Mauritania (AP) — The men move in rhythm, swaying in line and beating the ground with spindly tree branches as the sun sets over the barren and hostile Mauritanian desert. The crack of the wood against dry grass lands in unison, a technique perfected by more than a decade of fighting bushfires.

There is no fire today but the men — volunteer firefighters backed by the U.N. refugee agency — keep on training.

In this region of West Africa, bushfires are deadly. They can break out in the blink of an eye and last for days. The impoverished, vast territory is shared by Mauritanians and more than 250,000 refugees from neighboring Mali, who rely on the scarce vegetation to feed their livestock.

For the refugee firefighters, battling the blazes is a way of giving back to the community that took them in when they fled violence and instability at home in Mali.

Hantam Ag Ahmedou was 11 years old when his family left Mali in 2012 to settle in the Mbera refugee camp in Mauritania, 48 kilometers (30 miles) from the Malian border. Like most refugees and locals, his family are herders and once in Mbera, they saw how quickly bushfires spread and how devastating they can be.

“We said to ourselves: There is this amazing generosity of the host community. These people share with us everything they have," he told The Associated Press. "We needed to do something to lessen the burden."

His father started organizing volunteer firefighters, at the time around 200 refugees. The Mauritanians had been fighting bushfires for decades, Ag Ahmedou said, but the Malian refugees brought know-how that gave them an advantage.

“You cannot stop bushfires with water,” Ag Ahmedou said. “That’s impossible, fires sometimes break out a hundred kilometers from the nearest water source."

Instead they use tree branches, he said, to smother the fire.

"That’s the only way to do it,” he said.

Since 2018, the firefighters have been under the patronage of the UNHCR. The European Union finances their training and equipment, as well as the clearing of firebreak strips to stop the fires from spreading. The volunteers today count over 360 refugees who work with the region's authorities and firefighters.

When a bushfire breaks out and the alert comes in, the firefighters jump into their pickup trucks and drive out. Once at the site of a fire, a 20-member team spreads out and starts pounding the ground at the edge of the blaze with acacia branches — a rare tree that has a high resistance to heat.

Usually, three other teams stand by in case the first team needs replacing.

Ag Ahmedou started going out with the firefighters when he was 13, carrying water and food supplies for the men. He helped put out his first fire when he was 18, and has since beaten hundreds of blazes.

He knows how dangerous the task is but he doesn't let the fear control him.

“Someone has to do it,” he said. "If the fire is not stopped, it can penetrate the refugee camp and the villages, kill animals, kill humans, and devastate the economy of the whole region.”

About 90% of Mauritania is covered by the Sahara Desert. Climate change has accelerated desertification and increased the pressure on natural resources, especially water, experts say. The United Nations says tensions between locals and refugees over grazing areas is a key threat to peace.

Tayyar Sukru Cansizoglu, the UNHCR chief in Mauritania, said that with the effects of climate change, even Mauritanians in the area cannot find enough grazing land for their own cows and goats — so a “single bushfire” becomes life-threatening for everyone.

When the first refugees arrived in 2012, authorities cleared a large chunk of land for the Mbera camp, which today has more than 150,000 Malian refugees. Another 150,000 live in villages scattered across the vast territory, sometimes outnumbering the locals 10 to one.

Chejna Abdallah, the mayor of the border town of Fassala, said because of “high pressure on natural resources, especially access to water,” tensions are rising between the locals and the Malians.

Abderrahmane Maiga, a 52-year-old member of the “Mbera Fire Brigade,” as the firefighters call themselves, presses soil around a young seedling and carefully pours water at its base.

To make up for the vegetation losses, the firefighters have started setting up tree and plant nurseries across the desert — including acacias. This year, they also planted the first lemon and mango trees.

“It’s only right that we stand up to help people,” Maiga said.

He recalls one of the worst fires he faced in 2014, which dozens of men — both refugees and host community members — spent 48 hours battling. By the time it was over, some of the volunteers had collapsed from exhaustion.

Ag Ahmedou said he was aware of the tensions, especially as violence in Mali intensifies and going back is not an option for most of the refugees.

He said this was the life he was born into — a life in the desert, a life of food scarcity and "degraded land" — and that there is nowhere else for him to go. Fighting for survival is the only option.

“We cannot go to Europe and abandon our home," he said. "So we have to resist. We have to fight.”

For more on Africa and development: https://apnews.com/hub/africa-pulse

The Associated Press receives financial support for global health and development coverage in Africa from the Gates Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Boys play football as the sun sets in the Mbera Refugee Camp, near Bassikounou, Hodh El Chargui Region, Mauritania, Saturday Nov. 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Caitlin Kelly)

Members of the NGO SOS desert plant trees in Mbera Refugee Camp, near Bassikounou, Hodh El Chargui Region, Mauritania, Saturday Nov. 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Caitlin Kelly)

Plants flower in the dry desert plains of the Sahel bloom in Mbera Refugee Camp, near Bassikounou, Hodh El Chargui Region, Mauritania, Saturday Nov. 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Caitlin Kelly)

Mbera fire brigade members from the NGO SOS desert demonstrate the brushing technique used to extinguish fires in Mbera Refugee Camp, near Bassikounou, Hodh El Chargui Region, Mauritania, Saturday Nov. 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Caitlin Kelly)

Mbera fire brigade members from the NGO SOS desert demonstrate the brushing technique used to extinguish fires in Mbera Refugee Camp, near Bassikounou, Hodh El Chargui Region, Mauritania, Saturday Nov. 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Caitlin Kelly)