IDLIB, Syria (AP) — Suleiman Khalil was harvesting olives in a Syrian orchard with two friends four months ago, unaware the soil beneath them still hid deadly remnants of war.

The trio suddenly noticed a visible mine lying on the ground. Panicked, Khalil and his friends tried to leave, but he stepped on a land mine and it exploded. His friends, terrified, ran to find an ambulance, but Khalil, 21, thought they had abandoned him.

Click to Gallery

Suleiman Khalil, 21, who lost his leg in a landmine explosion while harvesting olives with his friends in a field, poses for a pictures with his siblings from left to right, Sakina, 8, Nahla, 9, and Aya, 5, at his home in the village of Qaminas, east of Idlib, Syria, Wednesday, April 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

Smoke billows as a landmine is detonated during a ministry of defence operation to clear explosives left behind by the Syrian army during the war, in agricultural land south of Idlib, Syria, Sunday, April 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

Suleiman Khalil, 21, who lost his leg in a landmine explosion while harvesting olives with his friends in a field, walks outside his home in the village of Qaminas, east of Idlib, Syria, Wednesday, April 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

Members of the ministry of defence clear landmines left behind by the Syrian army during the war, in agricultural land south of Idlib, Syria, Sunday, April 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

Shepherd Jalal Ma'rouf, 22, who lost a limb to a landmine while herding sheep in farmland recently recaptured from regime forces, watches his friends play at his home in Deir Sunbul village, south of Idlib, Wednesday, April 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

Suleiman Khalil, 21, who lost his leg in a landmine explosion while harvesting olives with his friends in a field, walks outside his home in the village of Qaminas, east of Idlib, Syria, Wednesday, April 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

Shepherd Jalal Ma'rouf, 22, rests his hands on the stump of the limb he lost to a landmine while herding sheep in farmland recently recaptured from regime forces, at his home in Deir Sunbul village, south of Idlib, Wednesday, April 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

Shepherd Jalal Ma'rouf, 22, shows the stump of the limb he lost to a landmine while herding sheep in farmland recently recaptured from regime forces, at his home in Deir Sunbul village, south of Idlib, Wednesday, April 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

Salah Swed, 28, visits the grave of his brother Mohammed, who was killed while trying to dismantle a landmine, in their village of Kafr Nabl, south of Idlib, Syria, Monday, April 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

Salah Swed , 28, holds a cellphone showing a picture of his brother Mohammed, killed while attempting to dismantle a landmine, as he visits his grave in their village of Kafr Nabl, south of Idlib, Syria, Monday, April 14, 2025.(AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

Members of the Ministry of Defence clear landmines left behind by the Syrian army during the war, in agricultural land south of Idlib, Syria, Sunday, April 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

Suleiman Khalil, 21, who lost his leg in a landmine explosion while harvesting olives with his friends in a field, talks with his father at their home in the village of Qaminas, east of Idlib, Syria, Wednesday, April 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

Land mines are seen in a field during a ministry of defence operation to clear and detonate explosives left by the Syrian army during the war, in agricultural land south of Idlib, Syria, Sunday, April 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

Suleiman Khalil, 21, who lost his leg in a landmine explosion while harvesting olives with his friends in a field, poses for a pictures with his siblings from left to right, Sakina, 8, Nahla, 9, and Aya, 5, at his home in the village of Qaminas, east of Idlib, Syria, Wednesday, April 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

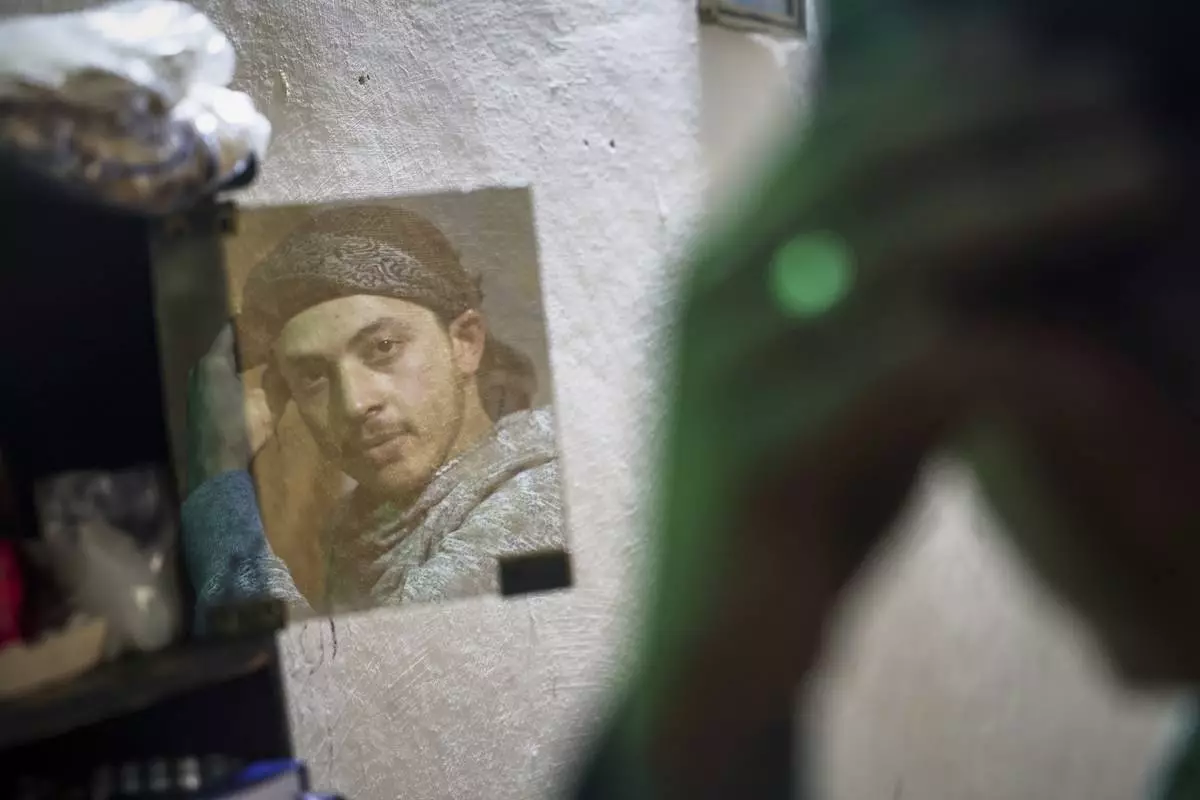

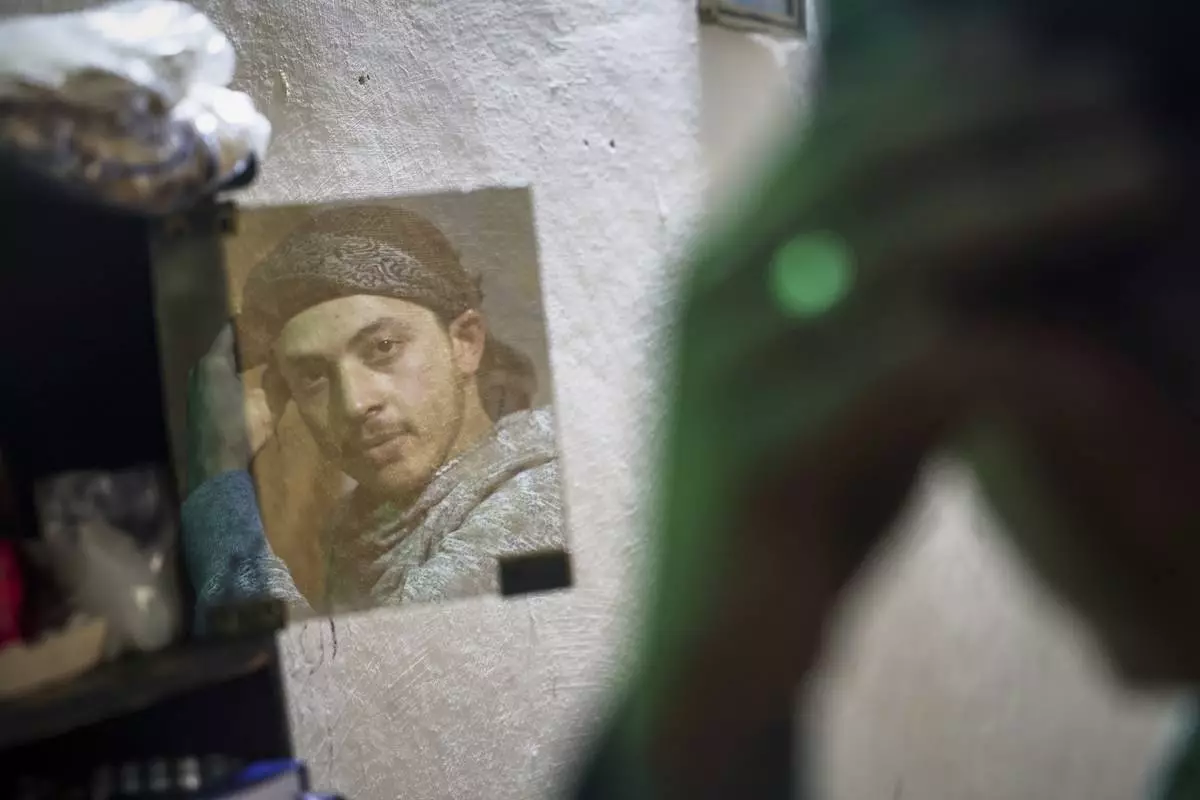

Suleiman Khalil, 21, who lost his leg in a landmine explosion while harvesting olives with his friends in a field, is reflected in a mirror at his home in the village of Qaminas, east of Idlib, Syria, Wednesday April 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

"I started crawling, then the second land mine exploded,” Khalil told The Associated Press. “At first, I thought I'd died. I didn’t think I would survive this.”

Khalil’s left leg was badly wounded in the first explosion, while his right leg was blown off from above the knee in the second. He used his shirt to tourniquet the stump and screamed for help until a soldier nearby heard him and rushed for his aid.

“There were days I didn’t want to live anymore,” Khalil said, sitting on a thin mattress, his amputated leg still wrapped in a white cloth four months after the explosions. Khalil, who is from the village of Qaminas, in the southern part of Syria’s Idlib province, is engaged and dreams of a prosthetic limb so he can return to work and support his family again.

While the nearly 14-year Syrian civil war came to an end with the fall of Bashar Assad on Dec. 8, war remnants continue to kill and maim. Contamination from land mines and explosive remnants has killed at least 249 people, including 60 children, and injured another 379 since Dec. 8, according to INSO, an international organization which coordinates safety for aid workers.

Mines and explosive remnants — widely used since 2011 by Syrian government forces, its allies, and armed opposition groups — have contaminated vast areas, many of which only became accessible after the Assad government’s collapse, leading to a surge in the number of land mine casualties, according to a recent Human Rights Watch (HRW) report.

Prior to Dec. 8, land mines and explosive remnants of war also frequently injured or killed civilians returning home and accessing agricultural land.

“Without urgent, nationwide clearance efforts, more civilians returning home to reclaim critical rights, lives, livelihoods, and land will be injured and killed,” said Richard Weir, a senior crisis and conflict researcher at HRW.

Experts estimate that tens of thousands of land mines remain buried across Syria, particularly in former front-line regions like rural Idlib.

“We don’t even have an exact number,” said Ahmad Jomaa, a member of a demining unit under Syria's defense ministry. “It will take ages to clear them all.”

Jomaa spoke while scanning farmland in a rural area east of Maarrat al-Numan with a handheld detector, pointing at a visible anti-personnel mine nestled in dry soil.

“This one can take off a leg,” he said. “We have to detonate it manually.”

Farming remains the main source of income for residents in rural Idlib, making the presence of mines a daily hazard. Days earlier a tractor exploded nearby, severely injuring several farm workers, Jomaa said. “Most of the mines here are meant for individuals and light vehicles, like the ones used by farmers,” he said.

Jomaa’s demining team began dismantling the mines immediately after the previous government was ousted. But their work comes at a steep cost.

“We’ve had 15 to 20 (deminers) lose limbs, and around a dozen of our brothers were killed doing this job,” he said. Advanced scanners, needed to detect buried or improvised devices, are in short supply, he said. Many land mines are still visible to the naked eye, but others are more sophisticated and harder to detect.

Land mines not only kill and maim but also cause long-term psychological trauma and broader harm, such as displacement, loss of property, and reduced access to essential services, HRW says.

The rights group has urged the transitional government to establish a civilian-led mine action authority in coordination with the UN Mine Action Service (UNMAS) to streamline and expand demining efforts.

Syria's military under the Assad government laid explosives years ago to deter opposition fighters. Even after the government seized nearby territories, it made little effort to clear the mines it left behind.

Standing before his brother’s grave, Salah Sweid holds up a photo on his phone of Mohammad, smiling behind a pile of dismantled mines. “My mother, like any other mother would do, warned him against going,” Salah said. “But he told them, ‘If I don’t go and others don’t go, who will? Every day someone is dying.’”

Mohammad was 39 when he died on Jan. 12 while demining in a village in Idlib. A former Syrian Republican Guard member trained in planting and dismantling mines, he later joined the opposition during the uprising, scavenging weapon debris to make arms.

He worked with Turkish units in Azaz, a city in northwest Syria, using advanced equipment, but on the day he died, he was on his own. As he defused one mine, another hidden beneath it detonated. After Assad’s ouster, mines littered his village in rural Idlib. He had begun volunteering to clear them — often without proper equipment — responding to residents’ pleas for help, even on holidays when his demining team was off duty, his brother said.

For every mine cleared by people like Mohammad, many more remain.

In a nearby village, Jalal al-Maarouf, 22, was tending to his goats three days after the Assad government’s collapse when he stepped on a mine. Fellow shepherds rushed him to a hospital, where doctors amputated his left leg.

He has added his name to a waiting list for a prosthetic, "but there’s nothing so far,” he said from his home, gently running a hand over the smooth edge of his stump. “As you can see, I can’t walk.” The cost of a prosthetic limb is in excess of $3,000 and far beyond his means.

Smoke billows as a landmine is detonated during a ministry of defence operation to clear explosives left behind by the Syrian army during the war, in agricultural land south of Idlib, Syria, Sunday, April 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

Suleiman Khalil, 21, who lost his leg in a landmine explosion while harvesting olives with his friends in a field, walks outside his home in the village of Qaminas, east of Idlib, Syria, Wednesday, April 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

Members of the ministry of defence clear landmines left behind by the Syrian army during the war, in agricultural land south of Idlib, Syria, Sunday, April 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

Shepherd Jalal Ma'rouf, 22, who lost a limb to a landmine while herding sheep in farmland recently recaptured from regime forces, watches his friends play at his home in Deir Sunbul village, south of Idlib, Wednesday, April 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

Suleiman Khalil, 21, who lost his leg in a landmine explosion while harvesting olives with his friends in a field, walks outside his home in the village of Qaminas, east of Idlib, Syria, Wednesday, April 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

Shepherd Jalal Ma'rouf, 22, rests his hands on the stump of the limb he lost to a landmine while herding sheep in farmland recently recaptured from regime forces, at his home in Deir Sunbul village, south of Idlib, Wednesday, April 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

Shepherd Jalal Ma'rouf, 22, shows the stump of the limb he lost to a landmine while herding sheep in farmland recently recaptured from regime forces, at his home in Deir Sunbul village, south of Idlib, Wednesday, April 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

Salah Swed, 28, visits the grave of his brother Mohammed, who was killed while trying to dismantle a landmine, in their village of Kafr Nabl, south of Idlib, Syria, Monday, April 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

Salah Swed , 28, holds a cellphone showing a picture of his brother Mohammed, killed while attempting to dismantle a landmine, as he visits his grave in their village of Kafr Nabl, south of Idlib, Syria, Monday, April 14, 2025.(AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

Members of the Ministry of Defence clear landmines left behind by the Syrian army during the war, in agricultural land south of Idlib, Syria, Sunday, April 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

Suleiman Khalil, 21, who lost his leg in a landmine explosion while harvesting olives with his friends in a field, talks with his father at their home in the village of Qaminas, east of Idlib, Syria, Wednesday, April 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

Land mines are seen in a field during a ministry of defence operation to clear and detonate explosives left by the Syrian army during the war, in agricultural land south of Idlib, Syria, Sunday, April 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

Suleiman Khalil, 21, who lost his leg in a landmine explosion while harvesting olives with his friends in a field, poses for a pictures with his siblings from left to right, Sakina, 8, Nahla, 9, and Aya, 5, at his home in the village of Qaminas, east of Idlib, Syria, Wednesday, April 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

Suleiman Khalil, 21, who lost his leg in a landmine explosion while harvesting olives with his friends in a field, is reflected in a mirror at his home in the village of Qaminas, east of Idlib, Syria, Wednesday April 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

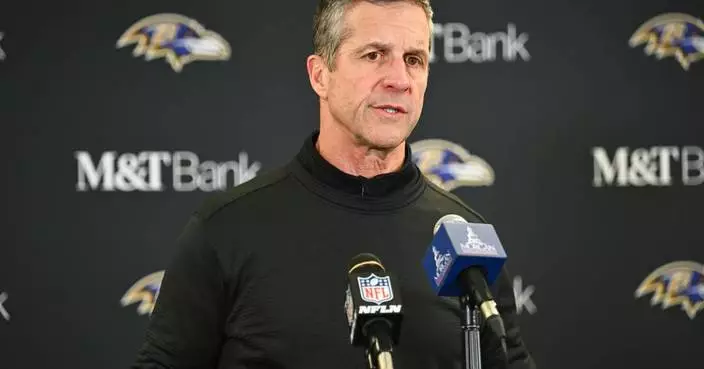

WASHINGTON (AP) — The Trump administration's criminal investigation of Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell appeared on Monday to be emboldening defenders of the U.S. central bank, who pushed back against President Donald Trump’s efforts to exert more control over the Fed.

The backlash reflected the overarching stakes in determining the balance of power within the federal government and the path of the U.S. economy at a time of uncertainty about inflation and a slowing job market. This has created a sense among some Republican lawmakers and leading economists that the Trump administration had overstepped the Fed's independence by sending subpoenas.

The criminal investigation — a first for a sitting Fed chair — sparked an unusually robust response from Powell and a full-throated defense from three former Fed chairs, a group of top economic officials and even Republican senators tasked with voting on Trump's eventual pick to replace Powell as Fed chair when his term expires in May.

White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt told reporters that Trump did not direct his Justice Department to investigate Powell, who has proven to be a foil for Trump by insisting on setting the Fed's benchmark interest rates based on the data instead of the president's wishes.

“One thing for sure, the president’s made it quite clear, is Jerome Powell is bad at his job,” Leavitt said. “As for whether or not Jerome Powell is a criminal, that’s an answer the Department of Justice is going to have to find out.”

The investigation demonstrates the lengths the Trump administration is willing to go to try to assert control over the Fed, an independent agency that the president believes should follow his claims that inflationary pressures have faded enough for drastic rate cuts to occur. Trump has repeatedly used investigations — which might or might not lead to an actual indictment — to attack his political rivals.

The risks go far beyond Washington infighting to whether people can find work or afford their groceries. If the Fed errs in setting rates, inflation could surge or job losses could mount. Trump maintains that an economic boom is occurring and rates should be cut to pump more money into the economy, while Powell has taken a more cautious approach in the wake of Trump's tariffs.

Several Republican senators have condemned the Department of Justice's subpoenas of the Fed, which Powell revealed Sunday and characterized as “pretexts” to pressure him to sharply cut interest rates. Powell also said the Justice Department has threatened criminal indictments over his June testimony to Congress about the cost and design elements of a $2.5 billion building renovation that includes the Fed's headquarters.

“After speaking with Chair Powell this morning, it’s clear the administration’s investigation is nothing more than an attempt at coercion,” said Sen. Lisa Murkowski, R-Alaska, on Monday.

Jeanine Pirro, U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia, said on social media that the Fed “ignored” her office’s outreach to discuss the renovation cost overruns, “necessitating the use of legal process — which is not a threat.”

“The word ‘indictment’ has come out of Mr. Powell’s mouth, no one else’s,” Pirro posted on X, although the subpoenas and the White House’s own statement about determining Powell's criminality would suggest the risk of an indictment.

A bipartisan group of former Fed chairs and top economists on Monday called the Trump administration's investigation “an unprecedented attempt to use prosecutorial attacks" to undermine the Fed's independence, stressing that central banks controlled by political leaders tend to produce higher inflation and lower growth.

“I think this is ham-handed, counter-productive, and going to set back the president’s cause,” said Jason Furman, an economist at Harvard and former top adviser to President Barack Obama. The investigation could also unify the Fed’s interest-rate setting committee in support of Powell, and means “the next Fed chair will be under more pressure to prove their independence.”

The subpoenas apply to Powell's statements before a congressional committee about the renovation of Fed buildings, including its marble-clad headquarters in Washington, D.C. They come at an unusual moment when Trump was teasing the likelihood of announcing his nominee this month to succeed Powell as the Fed chair and could possibly be self-defeating for the nomination process.

While Powell's term as chair ends in four months, he has a separate term as a Fed governor until January 2028, meaning that he could remain on the board. If Powell stays on the board, Trump could be blocked from appointing an outside candidate of his choice to be the chair.

Powell quickly found a growing number of defenders among Republicans in the Senate, who will have the choice of whether to confirm Trump's planned pick for Fed chair.

Sen. Thom Tillis, a North Carolina Republican and member of the Senate Banking panel, said late Sunday that he would oppose any of the Trump administration’s Fed nominees until the investigation is "resolved."

“If there were any remaining doubt whether advisers within the Trump Administration are actively pushing to end the independence of the Federal Reserve, there should now be none,” Tillis said.

Sen. Dave McCormick, R-Penn, said the Fed may have wasted public dollars with its renovation, but he said, “I do not think Chairman Powell is guilty of criminal activity.”

Senate Majority Leader John Thune offered a brief but stern response Monday about the tariffs as he arrived at the U.S. Capitol, suggesting that the administration needed “serious” evidence of wrongdoing to take such a significant step.

“I haven’t seen the case or whatever the allegations or charges are, but I would say they better, they better be real and they better be serious,” said Thune, a Republican representing South Dakota.

If Powell stays on the board after his term as chair ends, the Trump administration would be deprived of the chance to fill another seat that would give the administration a majority on the seven-member board. That majority could then enact significant reforms at the Fed and even block the appointment of presidents at the Fed's 12 regional banks.

“They could do a lot of reorganizing and reforms” without having to pass new legislation, said Mark Spindel, chief investment officer at Potomac River Capital and author of a book on Fed independence. “That seat is very valuable.”

Powell has declined at several press conferences to answer questions about his plans to stay or leave the board.

Scott Alvarez, former general counsel at the Fed, says the investigation is intended to intimidate Powell from staying on the board. The probe is occurring now “to say to Chair Powell, ’We’ll use every mechanism that the administration has to make your life miserable unless you leave the Board in May,'" Alvarez said.

Asked on Monday by reporters if Powell planned to remain a Fed governor, Kevin Hassett, director of the White House National Economic Council and a leading candidate to become Fed chair, said he was unaware of Powell’s plans.

“I’ve not talked to Jay about that,” Hassett said.

A bipartisan group of former Fed chairs and top economists said in their Monday letter that the administration’s legal actions and the possible loss of Fed independence could hurt the broader economy.

“This is how monetary policy is made in emerging markets with weak institutions, with highly negative consequences for inflation and the functioning of their economies more broadly,” the statement said.

The statement was signed by former Fed chairs Ben Bernanke, Janet Yellen, and Alan Greenspan, as well as former Treasury Secretaries Henry Paulson and Robert Rubin.

Still, Trump's pressure campaign had been building for some time, with him relentlessly criticizing and belittling Powell.

He even appeared to preview the shocking news of the subpoenas at a Dec. 29 news conference by saying he would bring a lawsuit against Powell over the renovation costs.

“He’s just a very incompetent man,” Trump said. “But we’re going to probably bring a lawsuit against him.”

__

AP writers Lisa Mascaro and Joey Cappelletti contributed to this report.

FILE - Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell, right, and President Donald Trump look over a document of cost figures during a visit to the Federal Reserve, July 24, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson, File)