ST. LOUIS (AP) — As pressure grows to get artificial colors out of the U.S. food supply, the shift may well start at Abby Tampow’s laboratory desk.

On an April afternoon, the scientist hovered over tiny dishes of red dye, each a slightly different ruby hue. Her task? To match the synthetic shade used for years in a commercial bottled raspberry vinaigrette — but by using only natural ingredients.

Click to Gallery

Sensient Technologies CEO Paul Manning speaks during an interview at a production facility for the color additive manufacturing company, in St. Louis., on Wednesday, April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

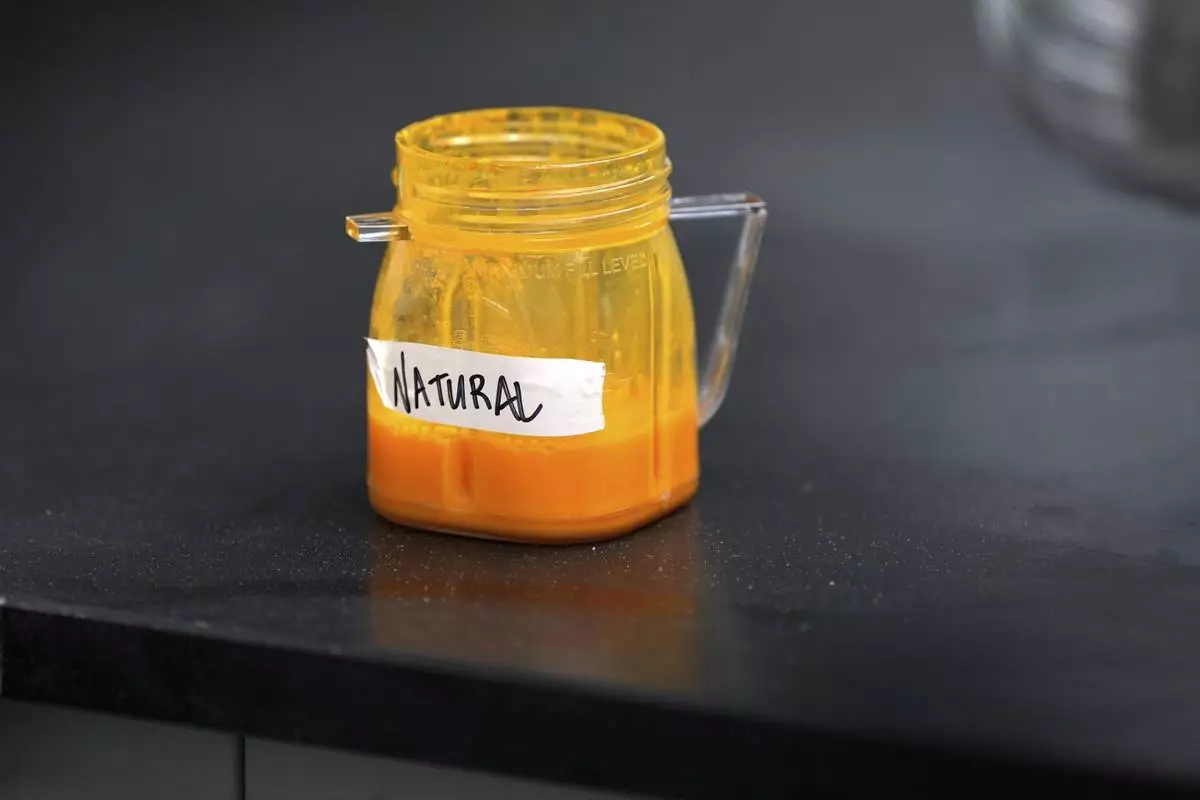

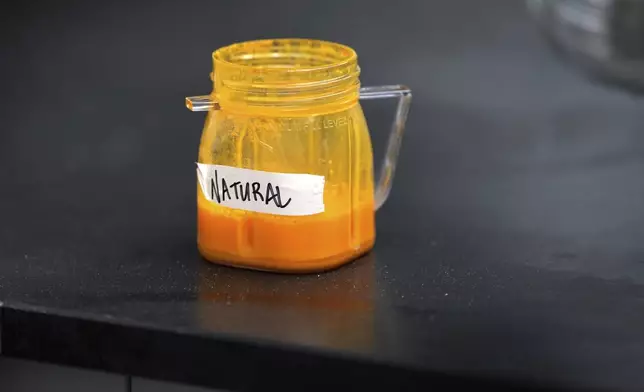

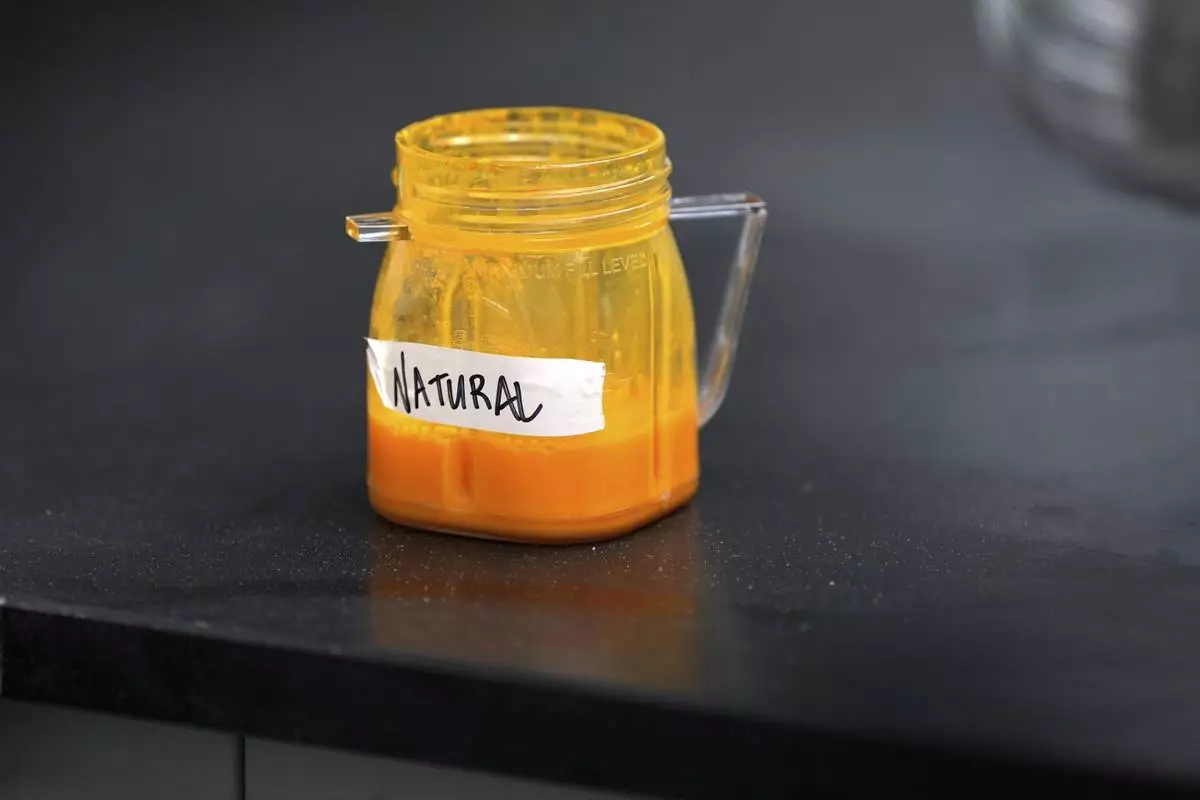

Natural food coloring is held in a jar in a lab at Sensient Technologies Corp., a color additive manufacturing company, in St. Louis., on Wednesday, April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

Applications Scientist Anuj Bag watches candy spin inside a drum while being coated with yellow coloring as he demonstrates the process of developing new food colors at Sensient Technologies Corp., a color additive manufacturing company, in St. Louis, on Wednesday, April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

Caleb Whorl pours a container of caramel coloring into a vat to be mixed before packaging at Sensient Technologies Corp., a color additive manufacturing company, in St. Louis, on Wednesday, April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

Jobe Washington, right, and Dwight Brown use a large sifter to mix a shade of yellow coloring at Sensient Technologies Corp., a color additive manufacturing company, in St. Louis, on Wednesday, April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

Containers of material wait in a warehouse for certification by the Food and Drug Administration at Sensient Technologies Corp., a color additive manufacturing company, in St. Louis., on Wednesday, April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

Bottles containing a variety of colored liquids sit on a shelf in a lab at Sensient Technologies Corp., a color additive manufacturing company, in St. Louis., on Wednesday, April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

Technician Heather Browning packages a color sample made of beet powder for a customer at Sensient Technologies Corp., a color additive manufacturing company, in St. Louis., on Wednesday, April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

Technician Heather Browning pours a liquid color sample into a smaller container to be shipped to a customer at Sensient Technologies Corp., a color additive manufacturing company, in St. Louis., on Wednesday, April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

Candy using food coloring are displayed in a lab at Sensient Technologies Corp., a color additive manufacturing company, in St. Louis., on Wednesday, April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

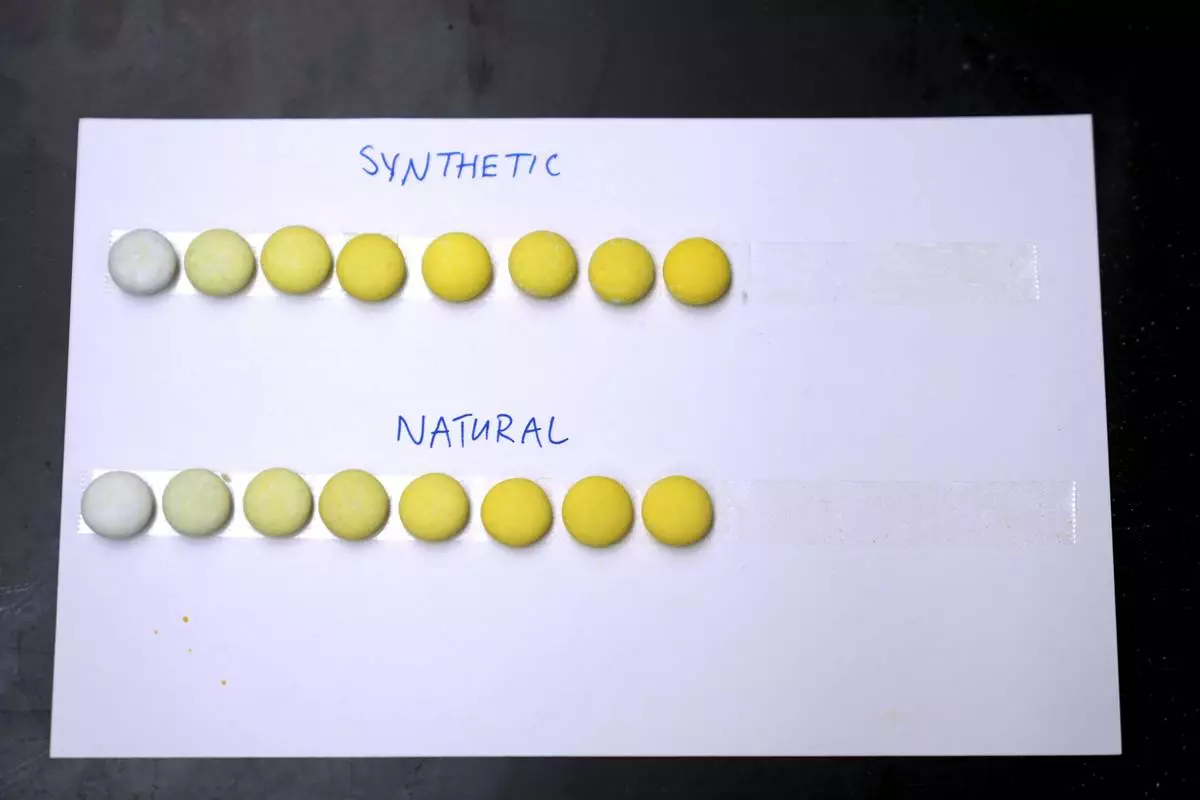

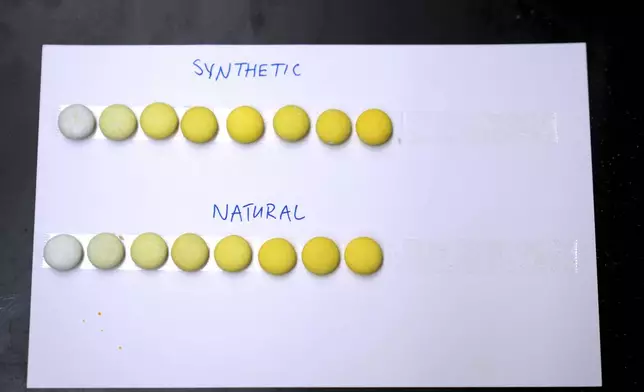

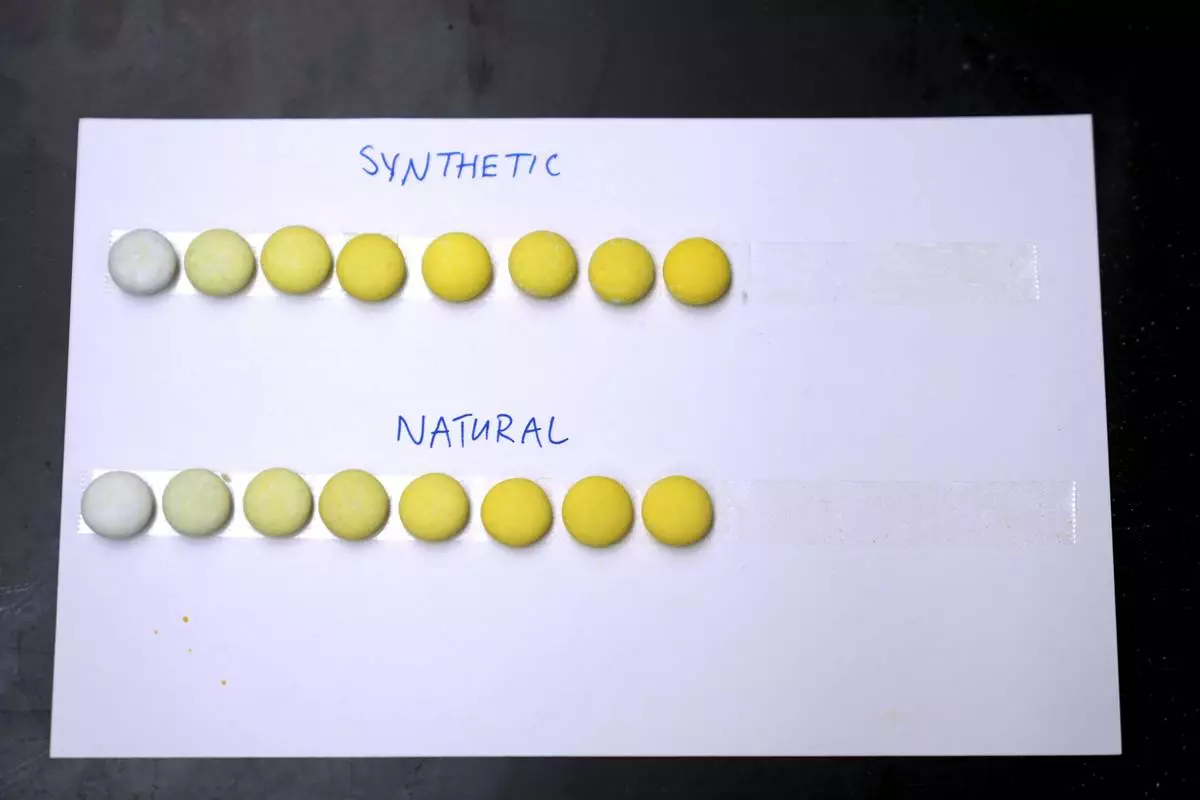

The results of various synthetic and natural food coloring are displayed inside a lab at Sensient Technologies Corp., a color additive manufacturing company, in St. Louis., on Wednesday, April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

Liquid color samples are stored in bottles in a room at Sensient Technologies Corp., a color additive manufacturing company, in St. Louis, on Wednesday, April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

Abby Tampow works in a Sensient Colors laboratory in St. Louis on April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Mary Conlon)

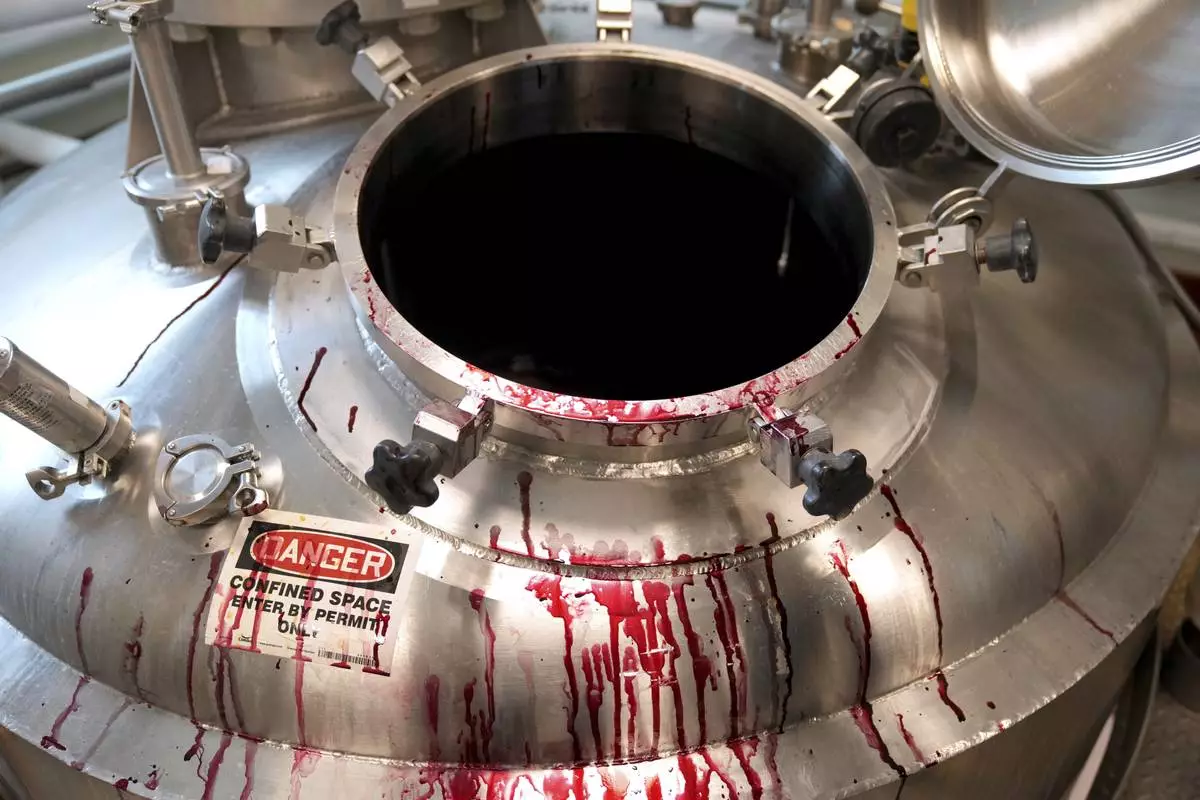

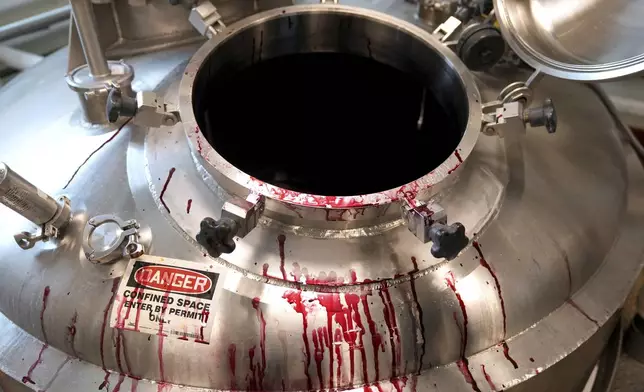

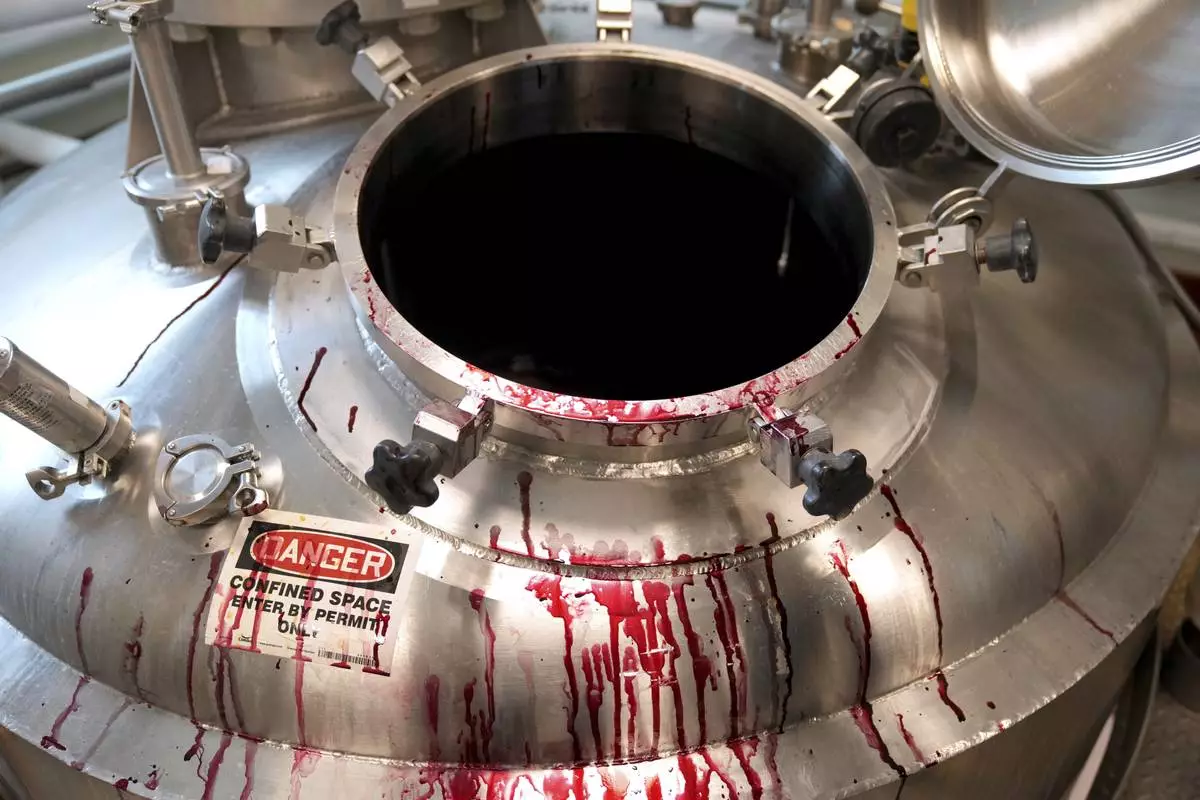

Beet juice is seen on a mixing tank used in the making of coloring at Sensient Technologies Corp., a color additive manufacturing company, in St. Louis, on Wednesday, April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

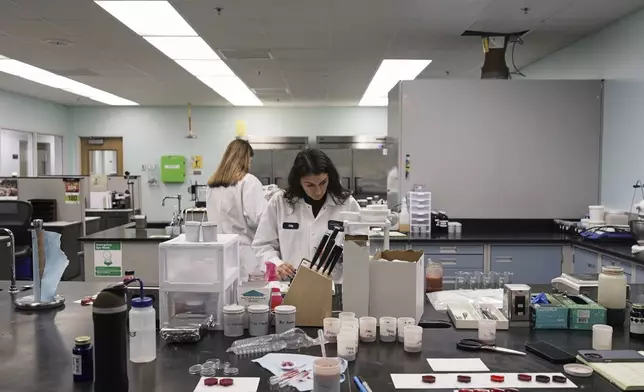

Senior Application Scientist Nicole Carey works in a lab to match food coloring at Sensient Technologies Corp., a color additive manufacturing company, in St. Louis, on Wednesday, April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

“With this red, it needs a little more orange,” Tampow said, mixing a slurry of purplish black carrot juice with a bit of beta-carotene, an orange-red color made from algae.

Tampow is part of the team at Sensient Technologies Corp., one of the world’s largest dyemakers, that is rushing to help the salad dressing manufacturer — along with thousands of other American businesses — meet demands to overhaul colors used to brighten products from cereals to sports drinks.

“Most of our customers have decided that this is finally the time when they’re going to make that switch to a natural color,” said Dave Gebhardt, Sensient’s senior technical director. He joined a recent tour of the Sensient Colors factory in a north St. Louis neighborhood.

Last week, U.S. health officials announced plans to persuade food companies to voluntarily eliminate petroleum-based artificial dyes by the end of 2026.

Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. called them “poisonous compounds” that endanger children’s health and development, citing limited evidence of potential health risks.

The federal push follows a flurry of state laws and a January decision to ban the artificial dye known as Red 3 — found in cakes, candies and some medications — because of cancer risks in lab animals. Social media influencers and ordinary consumers have ramped up calls for artificial colors to be removed from foods.

The Food and Drug Administration allows about three dozen color additives, including eight remaining synthetic dyes. But making the change from the petroleum-based dyes to colors derived from vegetables, fruits, flowers and even insects won’t be easy, fast or cheap, said Monica Giusti, an Ohio State University food color expert.

“Study after study has shown that if all companies were to remove synthetic colors from their formulations, the supply of the natural alternatives would not be enough,” Giusti said. “We are not really ready.”

It can take six months to a year to convert a single product from a synthetic dye to a natural one. And it could require three to four years to build up the supply of botanical products necessary for an industrywide shift, Sensient officials said.

“It’s not like there’s 150 million pounds of beet juice sitting around waiting on the off chance the whole market may convert,” said Paul Manning, the company's chief executive. “Tens of millions of pounds of these products need to be grown, pulled out of the ground, extracted.”

To make natural dyes, Sensient works with farmers and producers around the world to harvest the raw materials, which typically arrive at the plant as bulk concentrates. They’re processed and blended into liquids, granules or powders and then sent to food companies to be added to final products.

Natural dyes are harder to make and use than artificial colors. They are less consistent in color, less stable and subject to changes related to acidity, heat and light, Manning said. Blue is especially difficult. There aren't many natural sources of the color and those that exist can be hard to maintain during processing.

Also, a natural color costs about 10 times more to make than the synthetic version, Manning estimated.

“How do you get that same vividness, that same performance, that same level of safety in that product as you would in a synthetic product?” he said. “There’s a lot of complexity associated with that.”

Companies have long used the Red 3 synthetic dye to create what Sensient officials describe as “the Barbie pink.”

To create that color with a natural source might require the use of cochineal, an insect about the size of a peppercorn.

The female insects release a vibrant red pigment, carminic acid, in their bodies and eggs. The bugs live only on prickly pear cactuses in Peru and elsewhere. About 70,000 cochineal insects are needed to produce 1 kilogram, about 2.2 pounds, of dye.

“It's interesting how the most exotic colors are found in the most exotic places,” said Norb Nobrega, who travels the world scouting new hues for Sensient.

Artificial dyes are used widely in U.S. foods. About 1 in 5 food products in the U.S. contains added colors, whether natural or synthetic, Manning estimated. Many contain multiple colors.

FDA requires a sample of each batch of synthetic colors to be submitted for testing and certification. Color additives derived from plant, animal or mineral sources are exempt, but have been evaluated by the agency.

Health advocates have long called for the removal of artificial dyes from foods, citing mixed studies indicating they can cause neurobehavioral problems, including hyperactivity and attention issues, in some children.

The FDA says that the approved dyes are safe when used according to regulations and that “most children have no adverse effects when consuming foods containing color additives.”

But critics note that added colors are a key component of ultraprocessed foods, which account for more than 70% of the U.S. diet and have been associated with a host of chronic health problems, including heart disease, diabetes and obesity.

“I am all for getting artificial food dyes out of the food supply,” said Marion Nestle, a food policy expert. “They are strictly cosmetic, have no health or safety purpose, are markers of ultraprocessed foods and may be harmful to some children.”

Color is powerful driver of consumer behavior and changes can backfire, Giusti noted. In 2016, food giant General Mills removed artificial dyes from Trix cereal after requests from consumers, switching to natural sources including turmeric, strawberries and radishes.

But the cereal lost its neon colors, resulting in more muted hues — and a consumer backlash. Trix fans said they missed the bright colors and familiar taste of the cereal. In 2017, the company switched back.

“When it’s a product you already love, that you’re used to consuming, and it changes slightly, then it may not really be the same experience,” Giusti said. “Announcing a regulatory change is one step, but then the implementation is another thing.”

Kennedy, the health secretary, said U.S. officials have an “understanding” with food companies to phase out artificial colors. Industry officials told The Associated Press that there is no formal agreement.

However, several companies have said they plan to accelerate a shift to natural colors in some of their products.

PepsiCo CEO Ramon Laguarta said most of its products are already free of artificial colors, and that its Lays and Tostitos brands will phase them out by the end of this year. He said the company plans to phase out artificial colors — or at least offer consumers a natural alternative — over the next few years.

Representatives for General Mills said they’re “committed to continuing the conversation” with the administration. WK Kellogg officials said they are reformulating cereals used in the nation’s school lunch programs to eliminate the artificial dyes and will halt any new products containing them starting next January.

Sensient officials wouldn’t confirm which companies are seeking help making the switch, but they said they’re ready for the surge.

“Now that there’s a date, there’s the timeline,” Manning said. “It certainly requires action.”

Dee-Ann Durbin contributed reporting from Detroit.

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

This story has been updated to correct the spelling of Nobrega.

Sensient Technologies CEO Paul Manning speaks during an interview at a production facility for the color additive manufacturing company, in St. Louis., on Wednesday, April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

Natural food coloring is held in a jar in a lab at Sensient Technologies Corp., a color additive manufacturing company, in St. Louis., on Wednesday, April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

Applications Scientist Anuj Bag watches candy spin inside a drum while being coated with yellow coloring as he demonstrates the process of developing new food colors at Sensient Technologies Corp., a color additive manufacturing company, in St. Louis, on Wednesday, April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

Caleb Whorl pours a container of caramel coloring into a vat to be mixed before packaging at Sensient Technologies Corp., a color additive manufacturing company, in St. Louis, on Wednesday, April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

Jobe Washington, right, and Dwight Brown use a large sifter to mix a shade of yellow coloring at Sensient Technologies Corp., a color additive manufacturing company, in St. Louis, on Wednesday, April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

Containers of material wait in a warehouse for certification by the Food and Drug Administration at Sensient Technologies Corp., a color additive manufacturing company, in St. Louis., on Wednesday, April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

Bottles containing a variety of colored liquids sit on a shelf in a lab at Sensient Technologies Corp., a color additive manufacturing company, in St. Louis., on Wednesday, April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

Technician Heather Browning packages a color sample made of beet powder for a customer at Sensient Technologies Corp., a color additive manufacturing company, in St. Louis., on Wednesday, April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

Technician Heather Browning pours a liquid color sample into a smaller container to be shipped to a customer at Sensient Technologies Corp., a color additive manufacturing company, in St. Louis., on Wednesday, April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

Candy using food coloring are displayed in a lab at Sensient Technologies Corp., a color additive manufacturing company, in St. Louis., on Wednesday, April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

The results of various synthetic and natural food coloring are displayed inside a lab at Sensient Technologies Corp., a color additive manufacturing company, in St. Louis., on Wednesday, April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

Liquid color samples are stored in bottles in a room at Sensient Technologies Corp., a color additive manufacturing company, in St. Louis, on Wednesday, April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

Abby Tampow works in a Sensient Colors laboratory in St. Louis on April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Mary Conlon)

Beet juice is seen on a mixing tank used in the making of coloring at Sensient Technologies Corp., a color additive manufacturing company, in St. Louis, on Wednesday, April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

Senior Application Scientist Nicole Carey works in a lab to match food coloring at Sensient Technologies Corp., a color additive manufacturing company, in St. Louis, on Wednesday, April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

SYDNEY (AP) — Australian federal and state government leaders on Monday agreed to immediately overhaul already-tough national gun control laws after a mass shooting targeted a Hanukkah celebration on Sydney's Bondi Beach, leaving at least 15 people dead.

The action would include renegotiating the landmark national firearms agreement that virtually banned rapid-fire rifles after a lone gunman killed 35 people in Tasmania in 1996, galvanizing the country into action, the nine leaders' said in a statement after an emergency meeting.

The violence erupted at the end of a summer day when thousands had flocked to Bondi Beach, an icon of Australia’s cultural life. They included hundreds gathered for the “Chanukah by the Sea” event celebrating the start of the eight-day Hanukkah festival with food, face painting and a petting zoo.

At least 38 people, including two police officers, were being treated in hospitals after the massacre, when the two suspected shooters fired on the beachfront festivities. Those killed included a 10-year-old girl, a rabbi and a Holocaust survivor.

None of the dead or wounded victims have been formally named by the authorities. Identities of those killed, who ranged in age from 10 to 87, began to emerge in news reports Monday.

Among them was Rabbi Eli Schlanger, assistant rabbi at Chabad of Bondi and an organizer of the family Hanukkah event that was targeted, according to Chabad, an Orthodox Jewish movement that runs outreach worldwide and sponsors events during major Jewish holidays.

Israel’s Foreign Ministry confirmed the death of an Israeli citizen, but gave no further details. French President Emmanuel Macron said a French citizen, identified as Dan Elkayam, was among those killed.

Larisa Kleytman told reporters outside St Vincent’s Hospital in Sydney that her husband, Alexander Kleytman, was among the dead. The couple were both Holocaust survivors, according to The Australian newspaper.

Police shot the two suspected shooters, a father and son. The 50-year-old father died at the scene. His 24-year-old son remained in a coma in hospital on Monday, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said.

Police won't reveal their names.

Albanese confirmed that Australia’s main domestic spy agency, the Australian Security Intelligence Agency, had investigated the son for six months in 2019.

Australian Broadcasting Corp. reported that ASIO had examined the son’s ties to a Sydney-based Islamic State group cell. Albanese did not describe the associates, but said ASIO was interested in them rather than the son.

“He was examined on the basis of being associated with others and the assessment was made that there was no indication of any ongoing threat or threat of him engaging in violence,” Albanese said.

Albanese had proposed new gun restrictions, including limiting the number of guns a licensed owner can obtain and reviewing existing licenses over time.

His proposals were announced after the authorities revealed that the older suspected gunman had held a gun license for a decade and amassed his six guns legally.

“The government is prepared to take whatever action is necessary. Included in that is the need for tougher gun laws,” Albanese said.

The horror at Australia’s most popular beach was the deadliest shooting in almost three decades since the 1996 Port Arthur massacre. The removal of rapid-fire rifles has markedly reduced the death tolls from such acts of violence since then.

Albanese called the Bondi massacre an act of antisemitic terrorism that struck at the heart of the nation.

Government leaders on Monday proposed restricting gun ownership to Australian citizens, a measure that would have excluded the older suspect, who came to Australia in 1998 on a student visa and became a permanent resident after marrying a local woman. Officials wouldn’t confirm what country he had migrated from.

His son, who doesn't have a gun license, is an Australian-born citizen.

The government leaders also proposed the “additional use of criminal intelligence” in deciding who was eligible for a gun license. That could mean the son’s suspicious associates could disqualify the father from owning a gun.

Chris Minns, premier of New South Wales where Sydney is the state capital, said his state's gun laws would change, but he could not yet detail how.

“It means introducing a bill to Parliament to — I mean to be really blunt — make it more difficult to get these horrifying weapons that have no practical use in our community,” Minns said.

“If you’re not a farmer, you’re not involved in agriculture, why do you need these massive weapons that put the public in danger and make life dangerous and difficult for New South Wales Police?” Minns asked.

Meanwhile, the massacre provoked questions about whether Albanese and his government had done enough to curb rising antisemitism. Jewish leaders and the massacre’s survivors expressed fear and fury as they questioned why the men hadn’t been detected before they opened fire.

“There’s been a heap of inaction,” said Lawrence Stand, a Sydney man who raced to a bar mitzvah celebration in Bondi when the violence erupted to find his 12-year-old daughter.

“I think the federal government has made a number of missteps on antisemitism,” Alex Ryvchin, spokesperson for the Australian Council of Executive Jewry, told reporters gathered on Monday near the site of the massacre. “I think when an attack such as what we saw yesterday takes place, the paramount and fundamental duty of government is the protection of its citizens, so there’s been an immense failure.”

On Monday, hundreds arrived near the scene to lay flowers at a growing pile of floral tributes. There were words of pride, too, for a man who was captured on video appearing to tackle and disarm one gunman, before pointing the man’s weapon at him, then setting the gun on the ground.

The man was identified by Home Affairs Minister Tony Burke as Ahmed al Ahmed. The 42-year-old fruit shop owner and father of two was shot in the shoulder by the other gunman and survived.

Al Ahmed, an Australian citizen who migrated from Syria in 2006, underwent surgery on Monday, his family said.

“Ahmed is a real-life hero. Last night, his incredible bravery no doubt saved countless lives when he disarmed a terrorist at enormous personal risk,” Minns posted on social media with a photo of the premier sitting at the end of al Ahmed’s hospital bed.

Al Admed's parents, who moved to Australia in recent months, said their son had a background in the Syrian security forces.

“My son has always been brave. He helps people. He’s like that,” his mother, Malakeh Hasan al Ahmed, told ABC through an interpreter.

Australia, a country of 28 million people, is home to about 117,000 Jews, according to official figures. Over the past year, the country was rocked by antisemitic attacks in Sydney and Melbourne. Synagogues and cars were torched, businesses and homes graffitied and Jews attacked in those cities, where 85% of the nation’s Jewish population lives.

The Australian government has enacted various measures to counter a surge in antisemitism since Hamas attacked Israel on Oct. 7, 2023, and Israel launched a war on Hamas in Gaza in response.

Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said Sunday that he warned Australia’s leaders months ago about the dangers of failing to take action against antisemitism. He claimed Australia’s decision, in line with scores of other countries, to recognize a Palestinian state “pours fuel on the antisemitic fire.”

Albanese in August blamed Iran for two of the previous attacks and cut diplomatic ties to Tehran. Authorities have not suggested Iran was linked to Sunday’s massacre.

Graham-McLay reported from Wellington, New Zealand and McGuirk from Melbourne, Australia.

Governor General Sam Mostyn places flowers at a tribute to shooting victims outside the Bondi Pavilion at Sydney's Bondi Beach, Monday, Dec. 15, 2025, a day after a shooting. (AP Photo/Mark Baker)

Governor General Sam Mostyn, left, greets MP, Allegra Spender, at a gathering at a flower memorial to shooting victims outside the Bondi Pavilion at Sydney's Bondi Beach, Monday, Dec. 15, 2025, a day after a shooting. (AP Photo/Mark Baker)

A woman is escorted from a flower memorial outside the Bondi Pavilion at Sydney's Bondi Beach, Monday, Dec. 15, 2025, a day after a shooting. (AP Photo/Mark Baker)

A woman kneels and prays at a flower memorial to shooting victims outside the Bondi Pavilion at Sydney's Bondi Beach, Monday, Dec. 15, 2025, a day after a shooting. (AP Photo/Mark Baker)

A couple lay flowers at a tribute to shooting victims outside the Bondi Pavilion at Sydney's Bondi Beach, Monday, Dec. 15, 2025, a day after a shooting. (AP Photo/Mark Baker)