ATLANTA (AP) — It's what one historian calls an “elaborate, clunky machine,” one that's been fundamental to American democracy for more than two centuries.

The principle of “checks and balances” is rooted in the Constitution's design of a national government with three distinct, coequal branches.

President Donald Trump in his first 100 days tested that system like rarely before, signing dozens of executive orders, closing or sharply reducing government agencies funded by Congress, and denigrating judges who have issued dozens of rulings against him.

“The framers were acutely aware of competing interests, and they had great distrust of concentrated authority,” said Dartmouth College professor John Carey, an expert on American democracy. “That’s where the idea came from.”

Their road map has mostly prevented control from falling into “one person’s hands,” Carey said. But he warned that the system depends on “people operating in good faith ... and not necessarily exercising power to the fullest extent imaginable.”

Here's a look at checks and balances and previous tests across U.S. history.

The foundational checks-and-balances fight: President John Adams’ made last-minute appointments before he left office in 1801. His successor, Thomas Jefferson, and Secretary of State James Madison ignored them. William Marbury, an Adams justice of the peace appointee, asked the Supreme Court to compel Jefferson and Madison to honor Adams’ decisions.

Chief Justice John Marshall concluded in 1803 that the commissions became legitimate with Adams' signature and, thus, Madison acted illegally by shelving them. Marshall, however, stopped short of ordering anything. Marbury had sued under a 1789 law that made the Supreme Court the trial court in the dispute. Marshall's opinion voided that law because it gave justices – who almost exclusively hear appeals – more power than the Constitution afforded them.

The split decision asserted the court’s role in interpreting congressional acts -– and striking them down –- while also adjudicating executive branch actions.

Congress and President George Washington chartered the First Bank of the United States in 1791. Federalists, led by Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, favored a strong central government and wanted a national bank that could lend the government money. Anti-Federalists, led by Jefferson and Madison, wanted less centralized power and argued Congress had no authority to charter a bank. But they did not ask the courts to step in.

Andrew Jackson, the first populist president, loathed the bank, believing it to be a sop to the rich. Congress voted in 1832 to extend the charter, with provisions to mollify Jackson. The president vetoed the measure anyway, and Congress failed to muster the two-thirds majorities required by the Constitution to override him. In 1836, the Philadelphia-based bank became a private state bank.

During the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln suspended habeas corpus — a legal process that allows individuals to challenge their detention. That allowed federal authorities to arrest and hold people without granting due process. Lincoln said his maneuver might not be “strictly legal” but was a “public necessity” to protect the Union. The Supreme Court’s Roger Taney, sitting as a circuit judge, declared the suspension illegal but noted he did not have the power to enforce the opinion.

Congress ultimately sided with Lincoln through retroactive statutes. And the Supreme Court, in a separate 1862 case challenging other Lincoln actions, endorsed the president’s argument that the office comes with inherent wartime powers not expressly allowed via the Constitution or congressional act.

After the Civil War and Lincoln’s assassination, “Radical Republicans” in Congress wanted penalties on states that had seceded and on the Confederacy's leaders and combatants. They also advocated Reconstruction programs that enfranchised and elevated formerly enslaved people (the men, at least). President Andrew Johnson, a Tennessean, was more lenient on Confederates and harsher to formerly enslaved people. Congress, with appropriations power, established the Freedmen’s Bureau to assist newly freed Black Americans. Johnson, with pardon power, repatriated former Confederates. He also limited Freedmen’s Bureau authority to seize Confederates’ assets.

For a century, nearly all federal jobs were executive branch political appointments: revolving doors after every presidential transition. In 1883, Congress stepped in with the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act. Changes started with some posts being filled through examinations rather than political favor. Congress added to the law over generations, developing the civil service system that Trump is now seeking to dismantle by reclassifying tens of thousands of government employees. His aim is to turn civil servants into political appointees or other at-will workers who are more easily dismissed from their jobs.

After World War I, the Treaty of Versailles called for an international body to bring countries together to discuss global affairs and prevent war. President Woodrow Wilson advocated for the League of Nations. The Senate Foreign Relations Committee chairman, Republican Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts, brought the treaty to the Senate in 1919 with amendments to limit the League of Nation’s influence. Wilson opposed the caveats, and the Senate fell short of the two-thirds majority needed to ratify the treaty and join the League. After World War II, the U.S. took a lead role, with Senate support, in establishing the United Nations and the NATO alliance.

Franklin D. Roosevelt met the Great Depression with large federal programs and aggressive regulatory actions, much of it approved by Democratic majorities in Congress. A conservative Supreme Court struck down some of the New Deal legislation as beyond the scope of congressional power. Roosevelt answered by proposing to expand the nine-seat court and pressuring aging justices to retire. The president's critics dubbed it “a court-packing scheme.” He disputed the charge. But not even the Democratic Congress seriously entertained his idea.

Roosevelt ignored the unwritten rule, established by Washington, that a president serves no more than two terms. He won third and fourth terms during World War II, rankling even some of his allies. Soon after his death, a bipartisan coalition pushed the 22nd Amendment that limits presidents to being elected twice. Trump has talked about seeking a third term despite this constitutional prohibition.

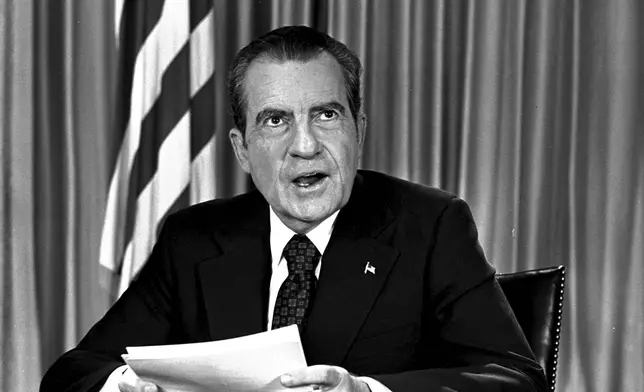

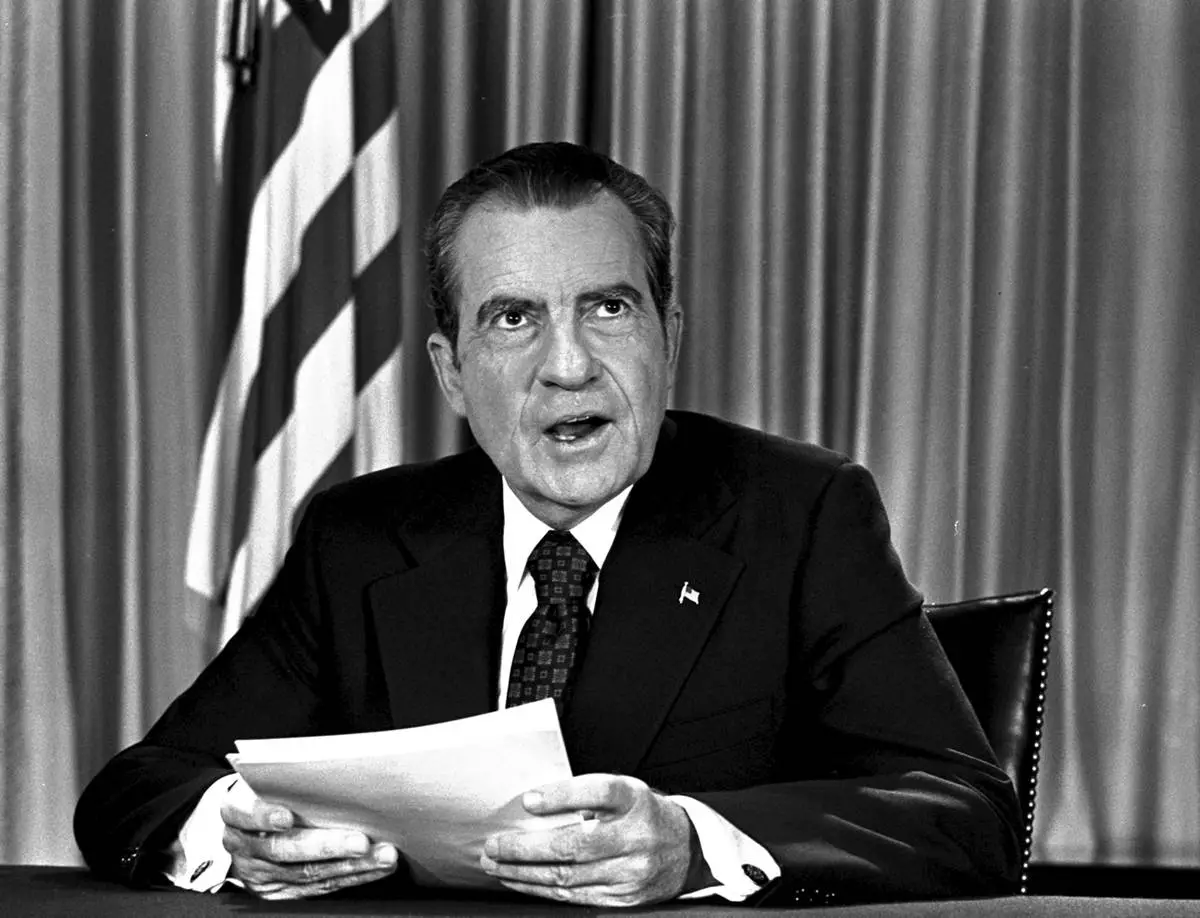

The Washington Post and other media exposed ties between President Richard Nixon's associates and a break-in at Democratic Party headquarters at the Watergate Hotel during the 1972 campaign. By summer 1974, the story ballooned into congressional hearings, court fights and plans for impeachment proceedings. The Supreme Court ruled unanimously against Nixon in his assertion that executive privilege allowed him not to turn over potential evidence of his and top aides' roles in the cover-up — including recordings of private Oval Office conversations. Nixon resigned after a delegation of his fellow Republicans told him that Congress was poised to remove him from office.

Presidents from John F. Kennedy through Nixon ratcheted up U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia during the Cold War. But Congress never declared war in Vietnam. A 1973 deal, under Nixon, ended official American military involvement. But complete U.S. withdrawal didn't occur until more than two years later – a period during which Congress reduced funding for South Vietnam's democratic government. Congress did not cut off all money for Saigon, as some conservatives later claimed. But lawmakers refused to rubber-stamp larger administration requests, asserting a congressional check on the president's military and foreign policy agenda.

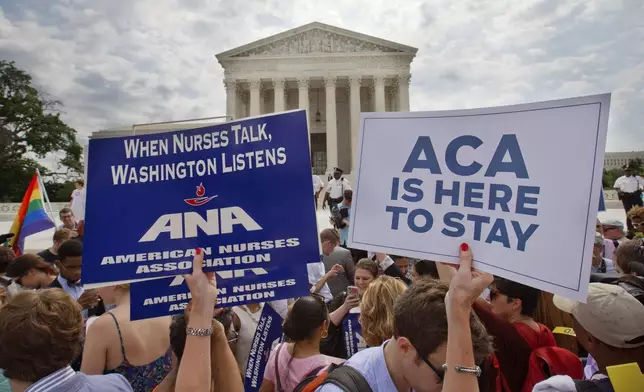

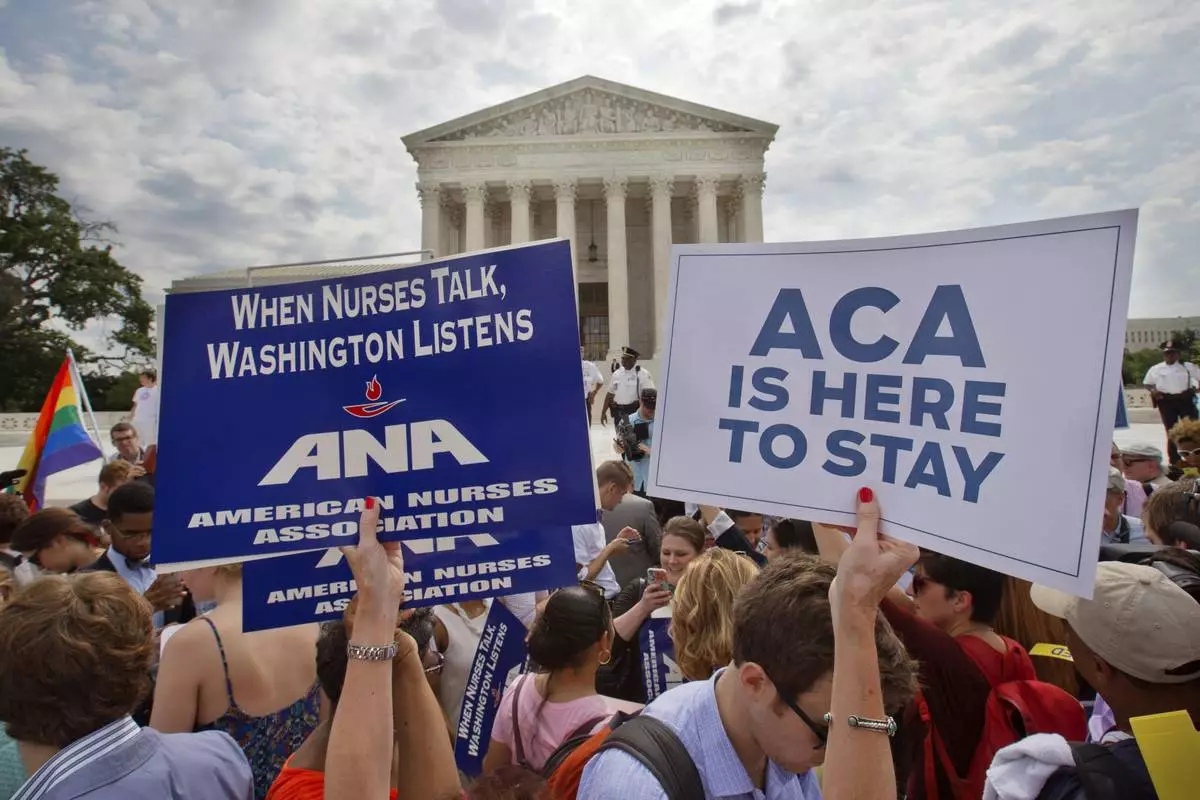

A Democratic-controlled Congress overhauled the nation’s health insurance system in 2010. The Affordable Care Act, in part, tried to require states to expand the Medicaid program that covers millions of children, disabled people and some low-income adults. But the Supreme Court ruled in 2012 that Congress and President Barack Obama could not compel states to expand the program by threatening to withhold other federal money already obligated to the states under previous federal law. The court on multiple occasions has upheld other portions of the law. Republicans, even when they have controlled the White House and Capitol Hill, have been unable to repeal the act.

FILE - President Richard Nixon sits in his White House office, Aug. 16, 1973, as he poses for pictures after delivering a nationwide television address dealing with Watergate. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - President Franklin D. Roosevelt delivers his first radio "Fireside Chat" in Washington in March 12, 1933. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - Supporters of the Affordable Care Act hold up signs as the opinion for health care is reported outside of the Supreme Court in Washington, June 25, 2015. The Supreme Court on Thursday upheld the nationwide tax subsidies under President Barack Obama's health care overhaul, in a ruling that preserves health insurance for millions of Americans. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin, File)

FILE - President Kennedy sits in his now famous rocking chair while talking with Nguyen Dinh Thuan, a top South Viet Nam official, at the White House in Washington on June 14, 1961. (AP Photo/Henry Burroughs, File)

FILE - President Barack Obama is applauded after signing the Affordable Care Act into law in the East Room of the White House in Washington, March 23, 2010. (AP Photo/Charles Dharapak, File)

FILE - A person holds a copy of the Constitution of the United States of America and Declaration of Independence at a May Day rally for the Rule of Law, May 1, 2025, in New York. (AP Photo/Adam Gray, File)