INDIANAPOLIS (AP) — FCS teams would be allowed to play 12 regular-season games every year under a Division I Football Championship Subdivision Oversight Committee recommendation.

The NCAA announced Tuesday the one-game extension would go into effect in 2026 if the Division I Council gives its approval during its June 24-25 meeting.

Current legislation permits 12 regular-season games in years when there are 14 Saturdays from the first permissible playing date through the last playing date in November. In all other years, only 11 regular-season contests are permitted.

The recommendation also would standardize the start date of the FCS season as the Thursday 13 weeks before the FCS championship bracket is released, which is the Saturday before Thanksgiving.

Football Bowl Subdivision teams have had 12-game regular seasons since 2006.

AP college football: https://apnews.com/hub/ap-top-25-college-football-poll and https://apnews.com/hub/college-football

FILE - South Dakota State wide receiver Jadon Janke (1) hurdles Drake linebacker J.R. Flood (7) during the first half of an NCAA college football game Sept. 16, 2023, in Minneapolis. (AP Photo/Abbie Parr, File)

CRANS-MONTANA, Switzerland (AP) — Dozens of people are presumed dead and about 100 injured, most of them seriously, following a fire at a Swiss Alps bar during a New Year’s celebration, police said Thursday.

“Several tens of people” were killed at the bar, Le Constellation, Valais Canton police commander Frédéric Gisler said.

Work is underway to identify the victims and inform their families but “that will take time and for the time being it is premature to give you a more precise figure," Gisler said.

Beatrice Pilloud, attorney general of the Valais Canton, said it was too early to determine the cause of the fire. Experts have not yet been able to go inside the wreckage.

“At no moment is there a question of any kind of attack,” Pilloud said.

Officials called the blaze an “embrasement généralisé,” a firefighting term describing how a blaze can trigger the release of combustible gases that can then ignite violently and cause what English-speaking firefighters would call a flashover or a backdraft.

“This evening should have been a moment of celebration and coming together, but it turned into a nightmare,” said Mathias Rénard, head of the regional government.

The injured were so numerous that the intensive care unit and operating theater at the regional hospital quickly hit full capacity, Rénard said.

Helicopters and ambulances rushed to the scene to assist victims, including some from different countries, officials said.

“We are devastated,” Frédéric Gisler, commander of the Valais Cantonal police, said during a news conference.

The injured were so numerous that the intensive care unit and operating theater at the regional hospital quickly hit full capacity, according to regional councilor Mathias Rénard.

The municipality had banned New Year’s Eve fireworks due to lack of rainfall in the past month, according to its website.

In a region busy with tourists skiing on the slopes, the authorities have called on the local population to show caution in the coming days to avoid any accidents that could require medical resources that are already overwhelmed.

The community is in the heart of the Swiss Alps, just 40 kilometers (25 miles) north of the Matterhorn, one of the most famous Alpine peaks, and 130 kilometers (81 miles) south of Zurich.

The highest point of Crans-Montana, with a population of 10,000 residents, sits at an elevation of nearly 3,000 meters (1.86 miles), according to the municipality’s website, which says officials are seeking to move away from a tourist culture and attract high-tech research and development.

The municipality was formed only nine years ago, on Jan. 1, 2017, when multiple towns merged. It extends over 590 hectares (2.3 square miles) from the Rhône Valley to the Plaine Morte glacier.

Crans-Montana is one of the top race venues on the World Cup circuit in Alpine skiing and will host the next world championships over two weeks in February 2027.

In four weeks’ time, the resort will host the best men’s and women’s downhill racers for their last events before going to the Milan Cortina Olympics, which open Feb. 6.

Crans-Montana also is a premium venue in international golf. The Crans-sur-Sierre club stages the European Masters each August on a picturesque course with stunning mountains views.

From left, Mathias Reynard, State Councillor and president of the Council of State of the Canton of Valais, Stephane Ganzer, State Councillor and head of the Department of Security, Institutions and Sport of the Canton of Valais, Frederic Gisler, Commander of the Valais Cantonal Police, Beatrice Pilloud, Attorney General of the Canton of Valais and Nicole Bonvin-Clivaz, Vice-President of the Municipal Council of Crans-Montana during a press conference in Lens, following a fire that broke out at the Le Constellation bar and lounge leaving people dead and injured, during New Year’s celebration, in Crans-Montana, Swiss Alps, Switzerland, Thursday, Jan. 1, 2026. (Alessandro della Valle/Keystone via AP)

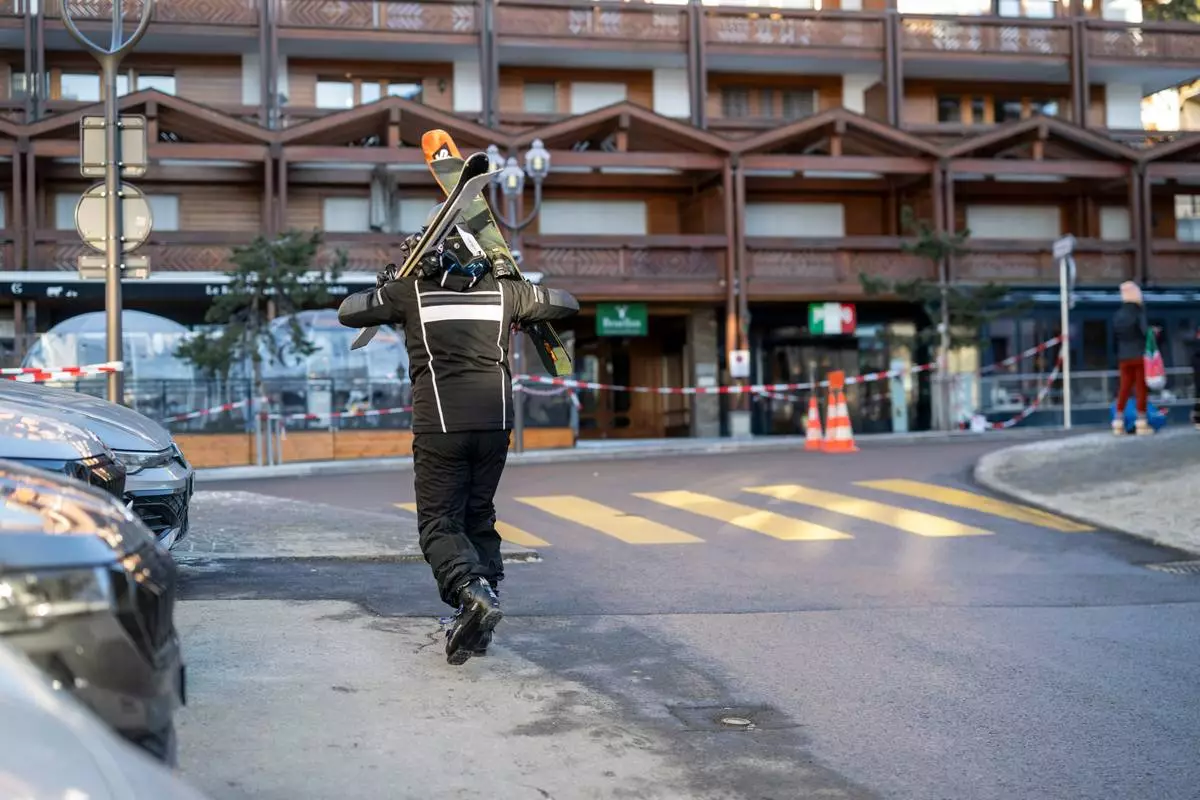

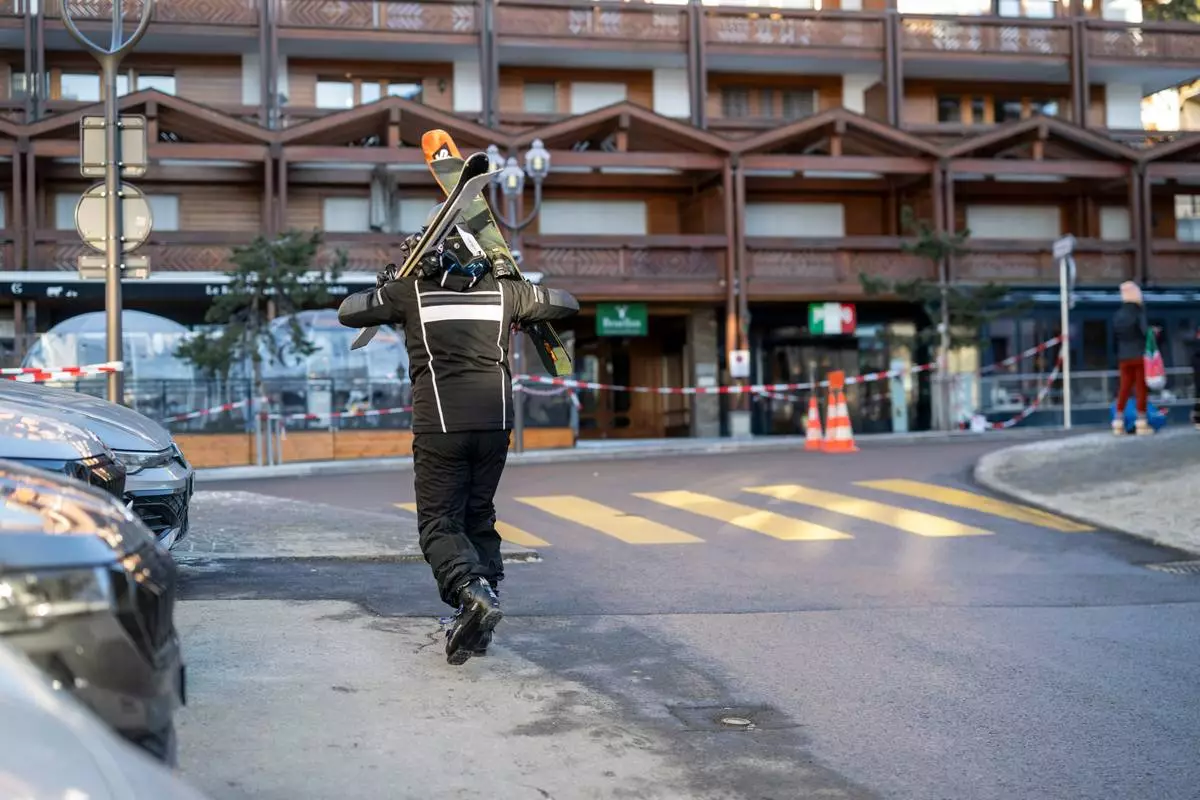

A skier walks in the area where a fire broke out at the Le Constellation bar and lounge leaving people dead and injured, during New Year’s celebration, in Crans-Montana, Swiss Alps, Switzerland, Thursday, Jan. 1, 2026. (Alessandro della Valle/Keystone via AP)

A banner stating that fireworks are prohibited due to the risk of fire is pictured near the area where a fire broke out at the Le Constellation bar and lounge leaving people dead and injured, during New Year’s celebration, in Crans-Montana, Swiss Alps, Switzerland, Thursday, Jan. 1, 2026. (Alessandro della Valle/Keystone via AP)

Police officers inspect the area where a fire broke out at the Le Constellation bar and lounge leaving people dead and injured, during New Year’s celebration, in Crans-Montana, Swiss Alps, Switzerland, Thursday, Jan. 1, 2026. (Alessandro della Valle/Keystone via AP)

Police officers inspect the area where a fire broke out at the Le Constellation bar and lounge leaving people dead and injured, during New Year’s celebration, in Crans-Montana, Swiss Alps, Switzerland, Thursday, Jan. 1, 2026. (Alessandro della Valle/Keystone via AP)

Police officers inspect the area where a fire broke out at the Le Constellation bar and lounge leaving people dead and injured, during New Year’s celebration, in Crans-Montana, Swiss Alps, Switzerland, Thursday, Jan. 1, 2026. (Alessandro della Valle/Keystone via AP)

Police officers inspect the area where a fire broke out at the Le Constellation bar and lounge leaving people dead and injured, during New Year’s celebration, in Crans-Montana, Swiss Alps, Switzerland, Thursday, Jan. 1, 2026. (Alessandro della Valle/Keystone via AP)