LONDON (AP) — Bernadette Dugasse was just a toddler when her family was forced to leave her birthplace. She didn’t get a chance to return until she was a grandmother.

Dugasse, 68, has spent most of her life in the Seychelles and the U.K., wondering what it would be like to set foot on the tropical island of Diego Garcia, part of the remote cluster of atolls in the middle of the Indian Ocean called the Chagos Islands.

Click to Gallery

Chagossian Bernadette Dugasse shows photos of a church in the Chagos Islands during an interview with The Associated Press, at her home in London, Tuesday, March 25, 2025. (AP Photo/Kin Cheung)

Chagossian Bernadette Dugasse pauses, during an interview with The Associated Press, at her home in London, Tuesday, March 25, 2025. (AP Photo/Kin Cheung)

Chagossian Bernadette Dugasse looks at a Chagos Islands map during an interview with The Associated Press, at her home in London, Tuesday, March 25, 2025. (AP Photo/Kin Cheung)

Chagossian Bernadette Dugasse shows sand and sea shells from the Chagos Islands during an interview with The Associated Press, at her home in London, Tuesday, March 25, 2025. (AP Photo/Kin Cheung)

Chagossian Bernadette Dugasse shows photos of the Chagos Islands during an interview with The Associated Press, at her home in London, Tuesday, March 25, 2025. (AP Photo/Kin Cheung)

Chagossian Bernadette Dugasse speaks, during an interview with The Associated Press, at her home in London, Tuesday, March 25, 2025. (AP Photo/Kin Cheung)

Chagossian Bernadette Dugasse looks at a Chagos Islands map during an interview with The Associated Press, at her home in London, Tuesday, March 25, 2025. (AP Photo/Kin Cheung)

Like hundreds of others native to the islands, Dugasse was kicked out of her homeland more than half a century ago when the British and U.S. governments decided to build an important military base there.

After years of fighting for the right to go home, Dugasse and other displaced islanders watched in despair Thursday as the U.K. government announced it was formally transferring the Chagos Islands’ sovereignty to Mauritius.

While political leaders spoke about international security and geopolitics, the deal meant only one thing for Chagossians: That the prospect of ever going back to live in their homeland now seems more out of reach than ever.

“We are the natives. We belong there,” said Dugasse, who has reluctantly settled in Crawley, a town south of London. “It made me feel enraged because I want to go home.”

Dugasse was born on the Chagos Islands, which had been under the administration of Mauritius, a former British colony, until 1965, when Britain split them away from Mauritius.

Mauritius gained independence in 1968, but the Chagos remained under British control and were named the British Indian Ocean Territory.

Dugasse was barely 2 years old when her family was deported to the Seychelles in 1958 after her father, a laborer, allegedly broke a work contract. They were never allowed back. Throughout the 1960s, many other islanders who thought they were leaving temporarily – for a holiday, or medical treatment -- would be told they cannot return to the Chagos.

It turned out that Britain was evicting the entire population of the Chago Islands -- about 1,500 people descended from African slaves and plantation workers –- so the U.S. military could build a base on the largest island, Diego Garcia.

By 1973, all Indigenous Chagossians were forced to leave. Thousands of islanders and their descendants are now spread around the world, most living in Mauritius, the U.K. and Seychelles. Most want to return home.

Britain’s government has acknowledged that its removal of islanders was wrong, and has granted many citizenship and set aside some funds to improve their lives. But it continues to bar Chagossians from returning and living in their homeland, citing defense and security concerns and “cost to the British taxpayer.”

Although the British government this week finalized a deal to transfer sovereignty of the Chagos to Mauritius, ending a long contested colonial legacy, there is no upside for Chagossians.

Dugasse and other islanders say they were completely excluded from political negotiations, and that Mauritius’ government is unlikely to grant them any right to return. Under the deal, which still needs Parliament's approval, Britain will lease back the Diego Garcia military base for at least 99 years. That means the island will be off-limits for the foreseeable feature.

“I don’t have a Mauritian passport. I don’t want to affiliate myself with Mauritius,” she said. “We have our own culture. We have our own identity. We are unique Indigenous people.”

Dugasse and another Diego Garcia native, Bertrice Pompe, sought to bring legal action against the British government over the deal to transfer the Chagos Islands to Mauritian control. They only managed to halt the signing of the deal by a few hours Thursday.

Pompe said it was a “very sad day” but she wasn’t giving up.

“The rights we’re asking for now, we’ve been fighting for for 60 years,” Pompe said outside a London courthouse. “Mauritius is not going to give that to us. So we need to keep fighting with the British government to listen to us.”

Human Rights Watch and other groups have urged Britain’s government to recognize the Chagossians’ right to return home, calling its failure to do so a “continuing colonial crime against humanity."

Dugasse — who received British citizenship but said she got no other compensation — has been allowed back to Diego Garcia just twice in recent years. Both times the visits were only possible with special permission from the U.K. government.

She described the island as a “mini-America,” populated by American service members and Filipino staffers. She visited the church where her parents were married and where she was baptized, but found her village cemetery and school in ruins.

And when she collected seashells and white sand from the beach, officials told her she wasn’t allowed to bring those home.

“I told them no — (the shells and the sand) are mine, not yours,” she said. “We were allowed there for only nine days, and every day I cried.”

Dugasse said her elderly mother, who lives in the Seychelles, would like to die on Diego Garcia. She doesn't think that's possible — and she is pessimistic that any of her children or grandchildren will get a chance to see where their family came from.

“Are we Chagossians always going to be nomads, going from place to place?" she asked. "Most of the natives are dying. What will happen? It’s time for us to set foot home.”

Chagossian Bernadette Dugasse shows photos of a church in the Chagos Islands during an interview with The Associated Press, at her home in London, Tuesday, March 25, 2025. (AP Photo/Kin Cheung)

Chagossian Bernadette Dugasse pauses, during an interview with The Associated Press, at her home in London, Tuesday, March 25, 2025. (AP Photo/Kin Cheung)

Chagossian Bernadette Dugasse looks at a Chagos Islands map during an interview with The Associated Press, at her home in London, Tuesday, March 25, 2025. (AP Photo/Kin Cheung)

Chagossian Bernadette Dugasse shows sand and sea shells from the Chagos Islands during an interview with The Associated Press, at her home in London, Tuesday, March 25, 2025. (AP Photo/Kin Cheung)

Chagossian Bernadette Dugasse shows photos of the Chagos Islands during an interview with The Associated Press, at her home in London, Tuesday, March 25, 2025. (AP Photo/Kin Cheung)

Chagossian Bernadette Dugasse speaks, during an interview with The Associated Press, at her home in London, Tuesday, March 25, 2025. (AP Photo/Kin Cheung)

Chagossian Bernadette Dugasse looks at a Chagos Islands map during an interview with The Associated Press, at her home in London, Tuesday, March 25, 2025. (AP Photo/Kin Cheung)

YANGON (AP) — Myanmar began a second round of voting Sunday in its first general election since a takeover that installed a military government five years ago.

Voting expanded to additional townships including some areas affected by the civil war between the military government and its armed opponents.

Polling stations opened at 6 a.m. local time in 100 townships across the country, including parts of Sagaing, Magway, Mandalay, Bago and Tanintharyi regions, as well as Mon, Shan, Kachin, Kayah and Kayin states. Many of those areas have recently seen clashes or remain under heightened security, underscoring the risks surrounding the vote.

The election is being held in three phases due to armed conflicts. The first round took place Dec. 28 in 102 of the country’s total 330 townships. A final round is scheduled for Jan. 25, though 65 townships will not take part because of fighting.

Myanmar has a two-house national legislature, totaling 664 seats. The party with a combined parliamentary majority can select the new president, who can name a Cabinet and form a new government. The military automatically receives 25% of seats in each house under the constitution.

Maj. Gen. Zaw Min Tun, the military government's spokesperson, told journalists on Sunday that the two houses of parliament will be convened in March, and the new government will take up its duties in April.

Critics say the polls organized by the military government are neither free nor fair and are an effort by the military to legitimize its rule after seizing power from the elected government of Aung San Suu Kyi in February 2021.

On Sunday, people in Yangon and Mandalay, the two largest cities in the country, were casting their ballots at high schools, government buildings and religious buildings.

At more than 10 polling stations visited by Associated Press journalists in Yangon and Mandalay, voter numbers ranged from about 150 at the busiest site to just a few at others, appearing lower than during the 2020 election when long lines were common.

The military government said there were more than 24 million eligible voters in the election, about 35% fewer than in 2020. The government called the turnout a success, claiming ballots were cast by more than 6 million people, about 52% of the more than 11 million eligible voters in the election's first phase.

Myo Aung, a chief minister of the Mandalay region, said more people turned out Sunday to vote than in the first phase.

“The weaknesses from Dec. 28 vote have been addressed, so I believe the Jan. 11 election to be well organized and successful,” he said.

Maung Maung Naing, who voted at a polling station in Mandalay’s Mahar Aung Myay township, said he wanted a government that will benefit the people.

“I only like a government that can make everything better for livelihoods and social welfare,” he said.

Sandar Min, an independent candidate from Yangon’s Latha township, said she decided to contest the election despite criticism because she wants to work with the government for the good of the country. She hopes the vote will bring change that reduces suffering.

“We want the country to be nonviolent. We do not accept violence as part of the change of the country,” Sandar Min said after casting a vote. “We care deeply about the people of this country.”

While more than 4,800 candidates from 57 parties are competing for seats in national and regional legislatures, only six parties are competing nationwide.

The first phase left the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party, or USDP, in a dominant position, winning nearly 90% of those contested seats in that phase in Pyithu Hluttaw, the lower house of parliament. It also won a majority of seats in regional legislatures.

Suu Kyi, Myanmar’s 80-year-old former leader, and her party aren’t participating in the polls. She is serving a 27-year prison term on charges widely viewed as spurious and politically motivated. Her party, the National League for Democracy, was dissolved in 2023 after refusing to register under new military rules.

Other parties also refused to register or declined to run under conditions they deem unfair, while opposition groups have called for a voter boycott.

Tom Andrews, a special rapporteur working with the U.N. human rights office, urged the international community Thursday to reject what he called a “sham election,” saying the first round exposed coercion, violence and political exclusion.

“You cannot have a free, fair or credible election when thousands of political prisoners are behind bars, credible opposition parties have been dissolved, journalists are muzzled, and fundamental freedoms are crushed,” Andrews said.

According to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, which keeps detailed tallies of arrests and casualties linked to the nation’s political conflicts, more than 22,000 people are detained for political offenses, and more than 7,600 civilians have been killed by security forces since 2021.

The army’s takeover triggered widespread peaceful protests that soon erupted into armed resistance, and the country slipped into a civil war.

A new Election Protection Law imposes harsh penalties and restrictions for virtually all public criticism of the polls. The authorities have charged more than 330 people under new electoral law for leafleting or online activity over the past few months.

Opposition organizations and ethnic armed groups had previously vowed to disrupt the electoral process.

On Sunday, attacks targeting polling stations and government buildings were reported in at least four of the 100 townships holding polls, with two administrative officials killed, independent online media, including Myanmar Now, reported.

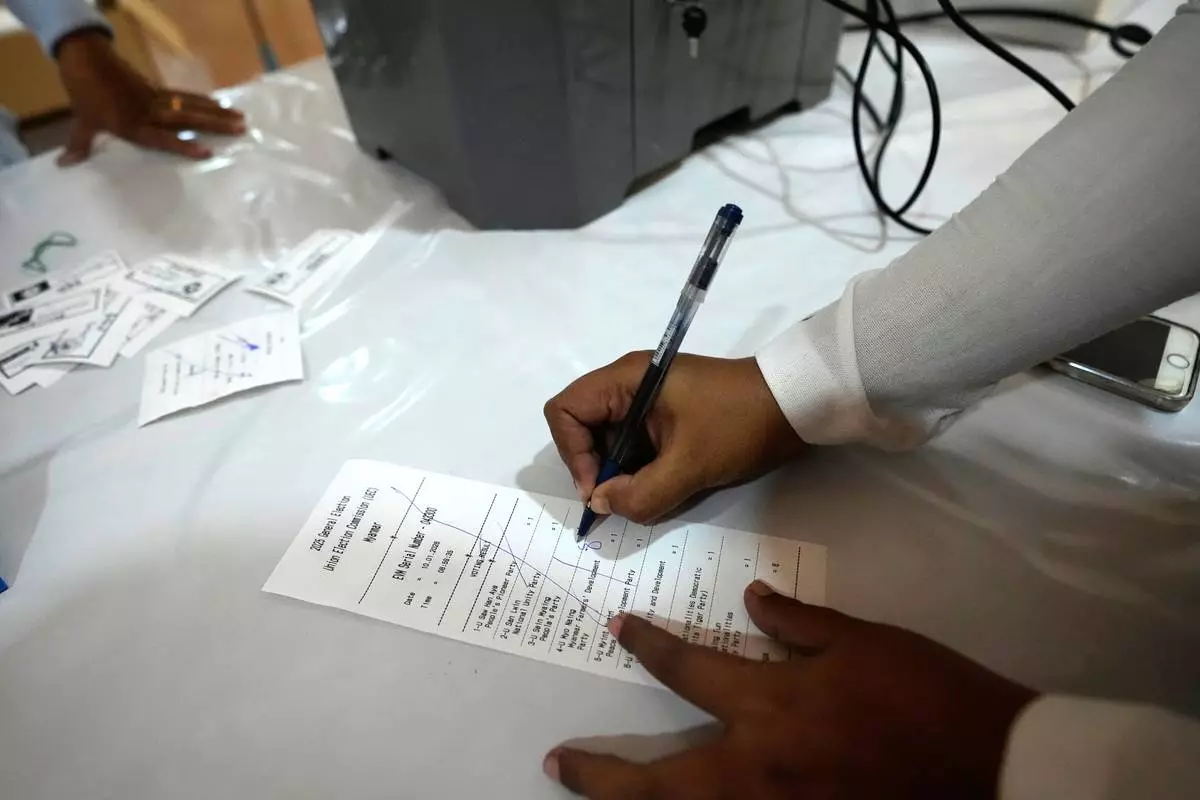

A voter casts ballot at a polling station during the second phase of general election Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026, in Yangon, Myanmar. (AP Photo/Thein Zaw)

A voter casts ballot at a polling station during the second phase of general election in Mandalay, central Myanmar, Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026. (AP Photo/Aung Shine Oo)

A voter shows his finger, marked with ink to indicate he voted, at a polling station during the second phase of general election in Mandalay, central Myanmar, Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026. (AP Photo/Aung Shine Oo)

Sandar Min, an individual candidate for an election and former parliament member from ousted leader Aung San Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy (NLD) party, shows off her finger marked with ink indicating she voted at a polling station during the second phase of general election Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026, in Yangon, Myanmar. (AP Photo/Thein Zaw)

Voters wait for a polling station to open during the second phase of general election in Mandalay, central Myanmar, Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026. (AP Photo/Aung Shine Oo)

Buddhist monks walk past a polling station opened at a monastery one day before the second phase of the general election in Yangon, Myanmar, Saturday, Jan. 10, 2026. (AP Photo/Thein Zaw)

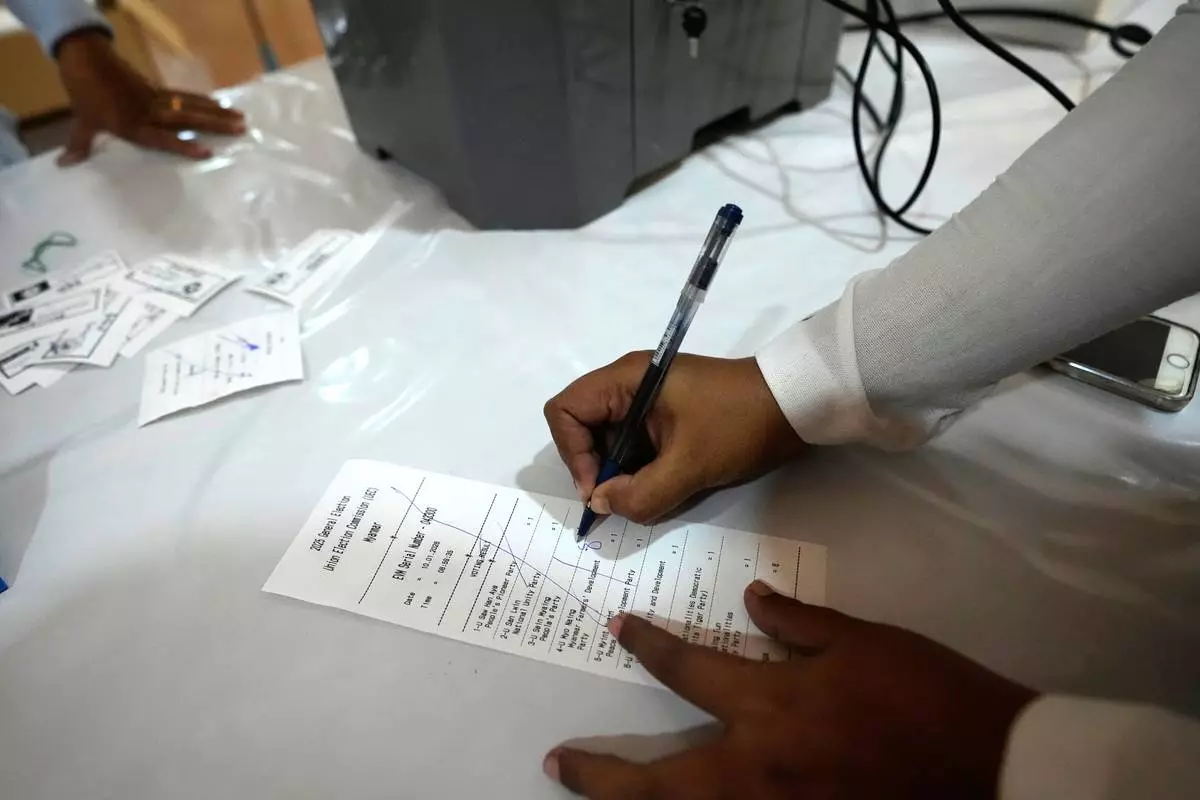

An official of the Union Election Commission checks a sample slip from an electronic voting machine as they prepare to set up a polling station opened at a monastery one day before the second phase of the general election in Yangon, Myanmar, Saturday, Jan. 10, 2026. (AP Photo/Thein Zaw)