BREMEN, Ga. (AP) — Singers at Holly Springs Primitive Baptist Church in West Georgia treat their red hymnals like extensions of themselves, never straying far from their copies of “The Sacred Harp” and its music notes shaped like triangles, ovals, squares and diamonds.

In four-part harmony, they sing together for hours, carrying on a more than 180-year-old American folk tradition that is as much about the community as it is the music.

It’s no accident “The Sacred Harp” is still in use today, and a new edition — the first in 34 years — is on its way.

Since the Christian songbook’s pre-Civil War publication, groups of Sacred Harp singers have periodically worked together to revise it, preserving its history and breathing new life into it. It’s a renewal, not a reprint, said David Ivey, a lifelong singer and chair of the Sacred Harp Publishing Company’s revision and music committee.

“That’s credited for keeping our book vibrant and alive,” said Ivey.

First published in 1844 by West Georgia editors and compilers Benjamin F. White and Elisha J. King, revisions of the shape-note hymnal make space for songs by living composers, said Jesse P. Karlsberg, a committee member and expert on the tradition.

“This is a book that was published before my great-grandparents were born and I think people will be singing from it long after I’m dead,” said Karlsberg, who met his wife through the a cappella group practice, which is central to his academic career. It's also his spiritual community.

“It's changed my life to become a Sacred Harp singer.”

The nine-member revision committee feels tremendous responsibility, said Ivey, who also worked on the most recent 1991 edition.

Sacred Harp singers are not historical reenactors, he said. They use their hymnals week after week. Some treat them like scrapbooks or family Bibles, tucking mementos between pages, taking notes in the margins and passing them down. Memories and emotions get attached to specific songs, and favorites in life can become memorials in death.

“The book is precious to people,” said Ivey, on a March afternoon surrounded by songbooks and related materials at the nonprofit publishing company’s museum in Carrollton, Georgia.

Sacred Harp singing is a remarkably well-documented tradition. The small, unassuming museum — about 50 miles (80 kilometers) west of Atlanta near the Alabama state line — stewards a trove of recordings and meeting minutes of singing events.

The upcoming edition is years in the making. The revision, authorized by the publishing company's board of directors in October 2018, was delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic. It now will be released in September at the annual convention of the United Sacred Harp Musical Association in Atlanta.

Ivey hopes singers fall in love with it, though he knows there is nervousness in the Sacred Harp community. For now, many of the changes are under wraps.

Assembled to be representative of the community, the committee is being methodical and making decisions through consensus, Ivey said. Though most will remain, some old songs will be cut and new ones added. They invited singer input, holding community meetings and singing events to help evaluate the more than 1,100 new songs submitted for consideration.

Sarah George, who met her husband through Sacred Harp and included it in their Episcopal wedding, hopes his compositions make the 2025 edition and their son grows up seeing his dad’s name in the songbook they will sing out of most weekends.

More so, George is wishing for a revival.

Her hope for "the revision is that it reminds people and reminds singers that we’re not doing something antiquated and folksy. We’re doing something that is a living, breathing worship tradition and music tradition,” said George, during a weekend of singing at Holly Springs.

Dozens gathered at the church for the Georgia State Sacred Harp Convention. Its back-to-back days of singing were interrupted by little other than potluck lunches and fellowship.

Sharing a pew with her daughter and granddaughter, Sheri Taylor explained that her family has sung from “The Sacred Harp” for generations. Her grandfather built a church specifically for singing events.

“I was raised in it,” said Taylor.

They've also known songwriters. Her daughter Laura Wood has fond childhood memories of singing with the late Hugh McGraw, a torchbearer of the tradition who oversaw the 1991 edition. While her mother is wary of the upcoming revision, knowing some songs won't be included, Wood is excited for it.

At Holly Springs, they joined the chorus of voices bouncing off the church's floor-to-ceiling wood planks and followed along in their songbooks. Wood felt connected to her family, especially her late grandmother.

“I can feel them with me,” she said.

Like all Sacred Harp events, it was not a performance. “The Sacred Harp” is meant to be sung by everyone — loudly.

Anyone can lead a song of their choosing from the hymnal's 554 options, but a song can only be sung once per event with few exceptions. Also called fa-sol-la singing, the group sight-reads the songs using the book's unique musical notations, sounding first its shape notes — fa, sol, la and mi — and then its lyrics.

“The whole idea is to make singing accessible to anyone,” said Karlsberg. “For many of us, it’s a moving and spiritual experience. It’s also a chance to see our dear friends.”

The shape-note tradition emerged from New England’s 18th century singing school movement that aimed to improve Protestant church music and expanded into a social activity. Over time, “The Sacred Harp” became synonymous with this choral tradition.

“The Sacred Harp” was designed to be neither denominational nor doctrinal, Karlsberg said. Many of its lyrics were composed by Christian reformers from England, such as Isaac Watts and Charles Wesley, he said. It was rarely used during church services.

Instead, the hymnal was part of the social fabric of the rural South, though racially segregated, Karlsberg said. Before emancipation, enslaved singers were part of white-run Sacred Harp events; post-Reconstruction, Black singers founded their own conventions, he said. “The Sacred Harp” eventually expanded to cities and beyond the South, including other countries.

“The Sacred Harp” is still sung in its hollow square formation. Singers organize into four voice parts: treble, alto, tenor and bass. Each group takes a side, facing an opening in the center where a rotating song leader guides the group and keeps time as dozens of voices come from all sides.

“It’s a high. I mean it’s just an almost indescribable feeling,” said Karen Rollins, a longtime singer and committee member.

At the museum, Rollins carefully turned the pages of her first edition copy of “The Sacred Harp,” and explained how the tradition is part of her fiber and faith. She often picks a Sunday singing over church.

“I like the fact that we can all sing — no matter who we are, what color, what religion, whatever — that we can sing with these people and never, never get upset talking about anything that might divide us,” she said.

Though many are Christian, Sacred Harp singers include people of other faiths and no faith, including LGBTQ+ community members who found church uncomfortable but miss congregational singing.

“It’s the good part of church for the people who grew up with it,” said Sam Kleinman, who stepped into the opening at Holly Springs to lead song No. 564 “Zion.” He is part of the vibrant shape-note singing community in New York City, that meets at St. John’s Lutheran Church near the historic Stonewall Inn.

Kleinman, who is Jewish but not observant, said he doesn’t have a religious connection to the lyrics and finds singing in a group cathartic.

Whereas Nathan Rees, a committee member and Sacred Harp museum curator, finds spiritual depth in the often-somber words.

“It just seems transcendent sometimes when you’re singing this, and you’re thinking about the history of the people who wrote these texts, the bigger history of just Christian devotion, and then also the history of music and this community,” he said.

At Holly Springs, Rees took his turn as song leader, choosing No. 374, “Oh, Sing with Me!” The group did as the 1859 song directed — loudly and in harmony like so many Sacred Harp singers before them.

“There’s no other experience to me that feels as elevating,” he said, “like you’re just escaping the world for a little while.”

This story has been updated to correct that“Oh, Sing with Me!” is from 1859, instead of 1895.

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

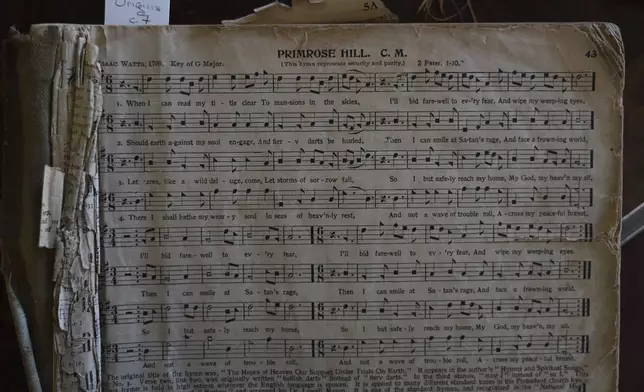

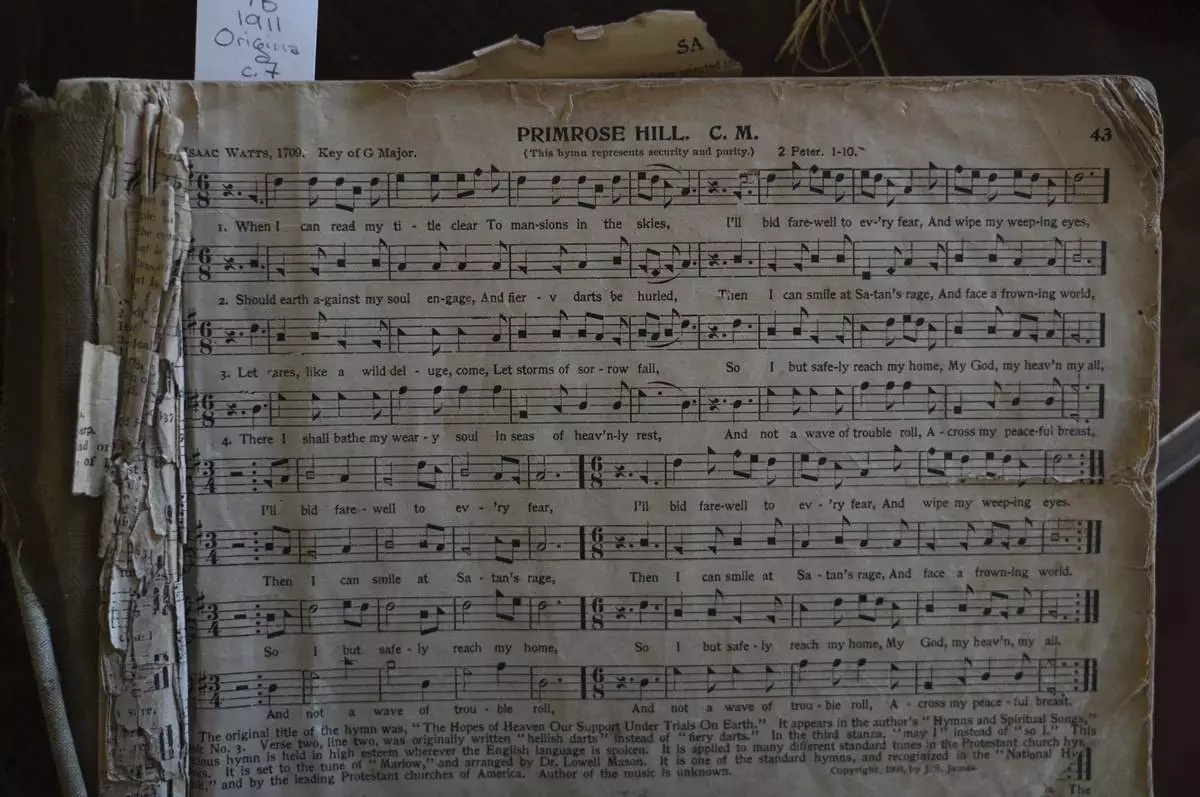

CORRECTS TO PRIMROSE, NOT PRIMEROSE - A 1911 edition of "The Sacred Harp," a shape-note hymnal from the 1800s, opened to song No. 43, "Primrose Hill," at the Sacred Harp Publishing Company and Museum in Carrollton, Ga., on Friday, March 21, 2025. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

In this photo provided by the Library of Congress, Hugh McGraw leads singers at the South Georgia Sacred Harp Singing Convention in Tifton, Ga., on May 1, 1977. (Howard W. Marshall/Library of Congress via AP)

Sacred Harp singers sit among the headstones at Holly Springs Primitive Baptist Church for a midday potluck in Bremen, Ga., on Saturday, March 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

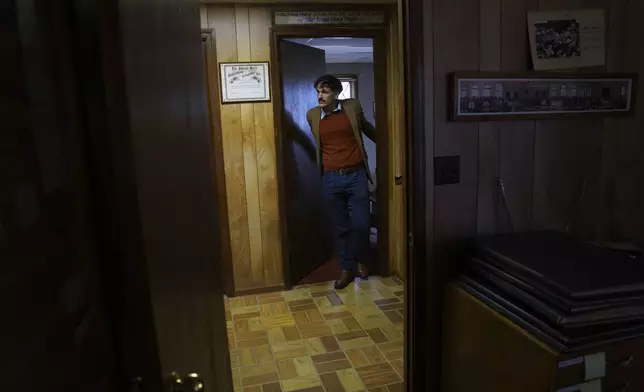

Nathan Rees, a committee member and Sacred Harp museum curator, at The Sacred Harp Publishing Company and Museum in Carrolton, Ga., on Friday, March 21, 2025. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

In this photo provided by the State Archives of Florida, M.L. Long leads sacred harp singers at the S.E. Alabama & Florida Union Sacred Harp Sing in Campbellton, Fla., on Nov. 24, 1980. (Peggy A. Bulger/State Archives of Florida via AP)

Rodney Ivey keeps time while singing from the tenor section at a Sacred Harp singing event at Holly Springs Primitive Baptist Church in Bremen, Ga., on Sunday, March 23, 2025. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

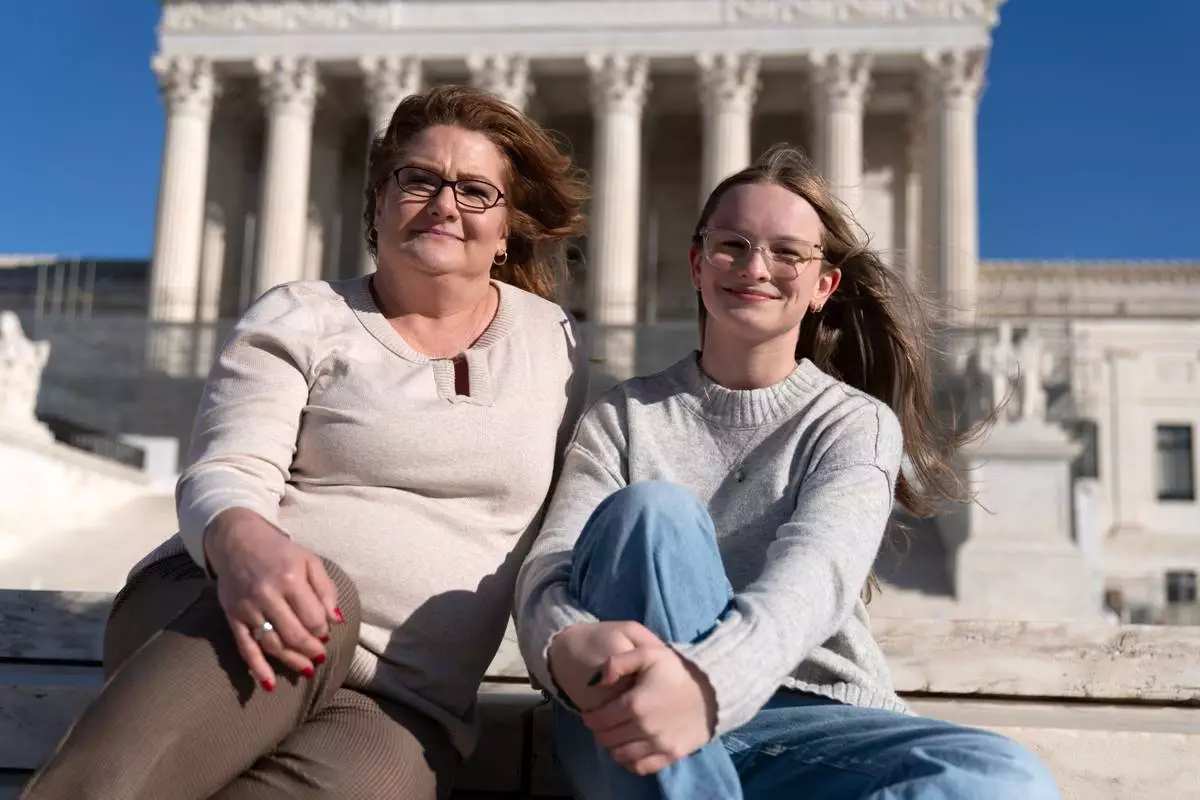

Sheri Taylor, left, sits with her daughter, Laura Wood, and granddaughter, Riley McKibbin, 11, while singing from "The Sacred Harp" in the tenor section at Holly Springs Primitive Baptist Church in Bremen, Ga., on Saturday, March 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

Sarah George, who met her husband through Sacred Harp singing, holds their son while leading a song from the hollow square at a Sacred Harp gathering in Bremen, Ga., at Holly Springs Primitive Baptist Church on Saturday, March 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

Isaac Green, 34, sings in the tenor section during a Sacred Harp singing event at Holly Springs Primitive Baptist Church in Bremen, Ga., on Sunday, March 23, 2025. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

Isaac Green, 34, covers his eyes while praying before a Sacred Harp singing event at Holly Springs Primitive Baptist Church in Bremen, Ga., on Sunday, March 23, 2025. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

Trees encircle Holly Springs Primitive Baptist Church, which has been a historical meeting site for Sacred Harp singers for generations, in Bremen, Ga., on Sunday, March 23, 2025. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

Matt Hinton, a shape-note singer, leads a song at a Sacred Harp singing event held at Holly Springs Primitive Baptist Church in Bremen, Ga., on Saturday, March 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

A 1911 edition of "The Sacred Harp," a shape-note hymnal from the 1800s, opened to song No. 43, "Primerose Hill," at the Sacred Harp Publishing Company and Museum in Carrollton, Ga., on Friday, March 21, 2025. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

Andy Ditzler stands in the center of a hollow square, "The Sacred Harp" formation in which singers organize into four voice parts and face each other to create an opening in the middle, at Holly Springs Primitive Baptist Church in Bremen, Ga., on Saturday, March 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)