BOISE, Idaho (AP) — The judge handling the trial of Bryan Kohberger in the killings of four Idaho college students said he would consider the defense team's request to delay the proceedings, but warned attorneys on both sides to be ready to go late next month anyway.

Fourth District Judge Steven Hippler said Wednesday that he would issue a written ruling on the trial timing soon.

“As of now, I would tell you it's likely you're going to trial on the date indicated,” Hippler said.

Kohberger, 30, a former graduate student in criminal justice at Washington State University, is charged with four counts of murder. Prosecutors say he sneaked into a rental home in nearby Moscow, Idaho, not far from the University of Idaho campus, and fatally stabbing Ethan Chapin, Xana Kernodle, Madison Mogen and Kaylee Goncalves on Nov. 13, 2022.

Kohberger stood silent at his arraignment, prompting a judge to enter a not guilty plea on his behalf. Prosecutors are seeking the death penalty.

Defense attorney Anne Taylor told the judge that proceeding with an August trial date would violate Kohberger's constitutional right to a fair trial in part because his attorneys are still reviewing evidence and struggling to get potential witnesses to agree to be interviewed.

“We have to review all discovery to present a full defense. We cannot present what we are not aware of,” Taylor said during the afternoon hearing. “I received discovery just last week — it is discovery that I have not reviewed yet.”

The defense team also needs more time to complete investigations and prepare mitigating evidence that could be presented if the case reaches the penalty phase, she said.

Prosecutor Josh Hurwit told the judge that having adequate time to prepare a defense is different from having unlimited time. He noted that Kohberger has three attorneys, two investigators, a mitigation expert and various other experts working on his case. The discovery materials turned over to the defense this week were mainly reports from prosecutors who were interviewing the defense team's own witnesses, he said.

The killings in Moscow, Idaho, drew worldwide attention almost immediately, prompting a judge to issue a sweeping gag order that bars attorneys, investigators and others from speaking publicly about the investigation or trial. The trial was moved to the state capital of Boise to gather a larger jury pool, and the judge has sealed many case documents.

It's all being done to limit potential juror's pretrial bias. Still, public interest remains high.

A recent Dateline episode included details that weren't publicly released, and Hippler said the information appears to have come from law enforcement or someone close to the case.

That's another reason to delay the trial, Kohberger's attorneys argued. Taylor told the judge that a delay would allow some of the impact from widespread publicity to dissipate.

“The Dateline episode wasn't just a one-time deal back in May,” Taylor said. “That continues to be talked about. Everything in this case continues to be talked about.”

Hurwit agreed that the media coverage will “pose challenges for jury selection.” But the issue isn't about the amount of publicity, he said, but whether impartial jurors can be selected for the trial. The court has already put a plan in place that will ensure an impartial jury is selected, he said, and delaying the trial because of publicity “puts us at the whim of the media.”

“What seems to be the strategy here is just to delay,” Hurwitt said of the defense motion.

The defense has asked the judge to appoint a special investigator to identify the leaker, and prosecutors said they will cooperate.

The media attention isn't likely to end soon. A book about the killings by James Patterson is set to be released in July. And a docuseries centered on the morning the deaths were discovered is expected to air on Amazon Prime next month, and includes interviews with some of the victims' family members and friends.

FILE - Bryan Kohberger, the man accused of fatally stabbing four University of Idaho students, is escorted into court for a hearing in Latah County District Court, Sept. 13, 2023, in Moscow, Idaho. (AP Photo/Ted S. Warren, Pool, File)

LONDON (AP) — In the past year, tens of thousands hostile to immigrants marched through London, chanting “send them home!” A British lawmaker complained of seeing too many non-white faces on TV. And senior politicians advocated the deportation of longtime U.K. residents born abroad.

The overt demonization of immigrants and those with immigrant roots is intensifying in the U.K. — and across Europe — as migration shoots up the political agenda and right-wing parties gain popularity.

In several European countries, political parties that favor mass deportations and depict immigration as a threat to national identity come at or near the top of opinion polls: Reform U.K., the AfD, or Alternative for Germany and France’s National Rally.

President Donald Trump, who recently called Somali immigrants in the U.S. “garbage” and whose national security strategy depicts European countries as threatened by immigration, appears to be endorsing and emboldening Europe's coarse, anti-immigrant sentiments.

Amid the rising tensions, Europe's mainstream parties are taking a harder line on migration and at times using divisive language about race.

“What were once dismissed as being at the far extreme end of far-right politics has now become a central part of the political debate,” said Kieran Connell, a lecturer in British history at Queen’s University Belfast.

Immigration has risen dramatically over the past decade in some European countries, driven in part by millions of asylum-seekers who have come to Europe fleeing conflicts in Africa, the Middle East and Ukraine.

Asylum-seekers account for a small percentage of total immigration, however, and experts say antipathy toward diversity and migration stems from a mix of factors. Economic stagnation in the years since the 2008 global financial crisis, the rise of charismatic nationalist politicians and the polarizing influence of social media all play a role, experts say.

In Britain, there is “a frightening increase in the sense of national division and decline” and that tends to push people toward political extremes, said Bobby Duffy, director of the Policy Unit at King’s College London. It took root after the financial crisis, was reinforced by Britain's debate about Brexit and deepened during the COVID-19 pandemic, Duffy said.

Social media has exacerbated the mood, notably on X, whose algorithm promotes divisive content and whose owner, Elon Musk, approvingly retweets far-right posts.

Across Europe, ethnonationalism has been promoted by right-wing parties such as Germany's AfD, France’s National Rally and the Fidesz party of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán.

Now it appears to have the stamp of approval from the Trump administration, whose new national security strategy depicts Europe as a collection of countries facing “economic decline” and “civilizational erasure” because of immigration and loss of national identities.

The hostile language alarmed many European politicians, but also echoed what they hear from their countries' far-right parties.

National Rally leader Jordan Bardella told the BBC he largely agreed with the Trump administration’s concern that mass immigration was “shaking the balance of European countries.”

Policies once considered extreme are now firmly on the political agenda. Reform UK, the hard-right party that consistently leads opinion polls, says if it wins power it will strip immigrants of permanent-resident status even if they have lived in the U.K. for decades. The center-right opposition Conservatives say they will deport British citizens with dual nationality who commit crimes.

A Reform UK lawmaker complained in October that advertisements were “full of Black people, full of Asian people.” Conservative justice spokesman Robert Jenrick remarked with concern that he “didn’t see another white face” in an area of Birmingham, Britain’s second-largest city. Neither politician had to resign.

Many proponents of reduced immigration say they are concerned about integration and community cohesion, not race. But that's not how it feels to those on the receiving end of racial abuse.

“There is no doubt it has worsened,” said Dawn Butler, a Black British lawmaker who says the vitriol she receives on social media “is increasing drastically, and has escalated into death threats.”

U.K. government statistics show police in England and Wales recorded more than 115,000 hate crimes in the year to March 2025, a 2% increase over the previous 12 months.

In July 2024, anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim violence erupted on Britain’s streets after three girls were stabbed to death at a Taylor Swift-themed dance class. Authorities said online misinformation wrongly identifying the U.K.-born teenage attacker as a Muslim migrant played a part.

In Ireland and in the Netherlands, protesters often demonstrate outside municipal meetings in communities where a new asylum center is proposed. Some protests have turned violent, with opponents of asylum-seekers throwing fireworks at riot police.

Across Europe, the main focus of protests has been hotels and other housing for asylum-seekers, which some say become magnets for crime and bad behavior. But the agenda of protest organizers is often much wider.

In September, more than 100,000 people chanting “We want our country back” marched through London in a protest organized by a far-right activist and convicted fraudster Tommy Robinson. Among the speakers was French far-right politician Eric Zemmour, who told the crowd that France and the U.K. both faced “the great replacement of our European people by peoples coming from the south and of Muslim culture.”

Mainstream European politicians condemn the “great replacement” conspiracy theory. Britain’s center-left Labour Party government has denounced racism and says migration is an important part of Britain’s national story.

At the same time, it is taking a tougher line on immigration, announcing policies to make it harder for migrants to settle permanently. The government says it is inspired by Denmark, which has seen asylum applications plummet since it started giving refugees only short-term residence.

Denmark and Britain are among a group of European countries pushing to weaken legal protections for migrants and make deportations easier.

Human rights advocates argue that attempts to appease the right just lead to ever-more-extreme policies.

“For every inch yielded, there’s going to be another inch demanded,” Council of Europe human rights commissioner Michael O’Flaherty told The Guardian. “Where does it stop? For example, the focus right now is on migrants, in large part. But who is it going to be about next time around?”

Politicians of the political center also have been criticized for adopting the language of the far right. British Prime Minister Keir Starmer said in May that Britain risked becoming an “island of strangers,” a phrase that echoed a notorious 1968 anti-immigration speech by the politician Enoch Powell. Starmer later said he had been unaware of the echo and regretted using the phrase.

Germany’s center-right Chancellor Friedrich Merz has hardened his language on migrants as the Alternative for Germany has grown more powerful. Merz caused an uproar in October by saying Germany had a problem with its “Stadtbild,” a word that translates as “city image” or cityscape. Critics felt Merz was implying that people who don’t look German don’t truly belong.

Merz later stressed that “we need immigration,” without which certain sectors of the economy, including health care, would cease to function.

Duffy said politicians should be responsible and consider how their rhetoric shapes public attitudes — though he added that's “quite a forlorn hope.”

"The perception that this divisiveness works has taken hold,” he said.

An earlier version of this story gave an incorrect name for the Alternative for Germany party.

Associated Press writers Mike Corder in The Hague, John Leicester in Paris, Suman Naishadham in Madrid, Sam McNeil in Brussels and Kirsten Grieshaber in Berlin contributed to this story.

FILE - The leader of France's National Rally (RN) Jordan Bardella arrives as he attends at the French far-right party national rally near the parliament in support of Marine Le Pen in Paris, Sunday, April 6, 2025. (AP Photo/Michel Euler, File)

FILE - Stickers are offered at the re-founding of the AfD youth organization in Giessen, Germany, early Saturday, Nov. 29, 2025. (AP Photo/Martin Meissner, File)

FILE - People demonstrate during the Tommy Robinson-led Unite the Kingdom march and rally, in London, Saturday Sept. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Joanna Chan, File)

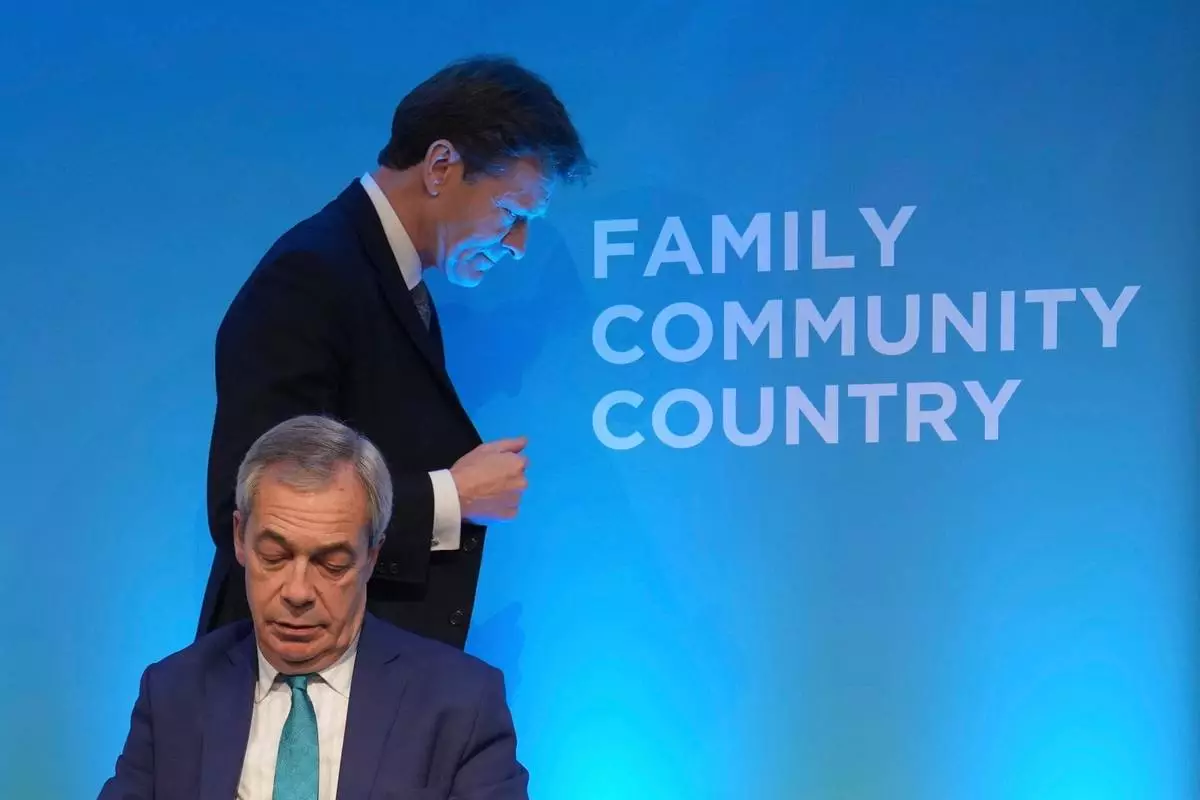

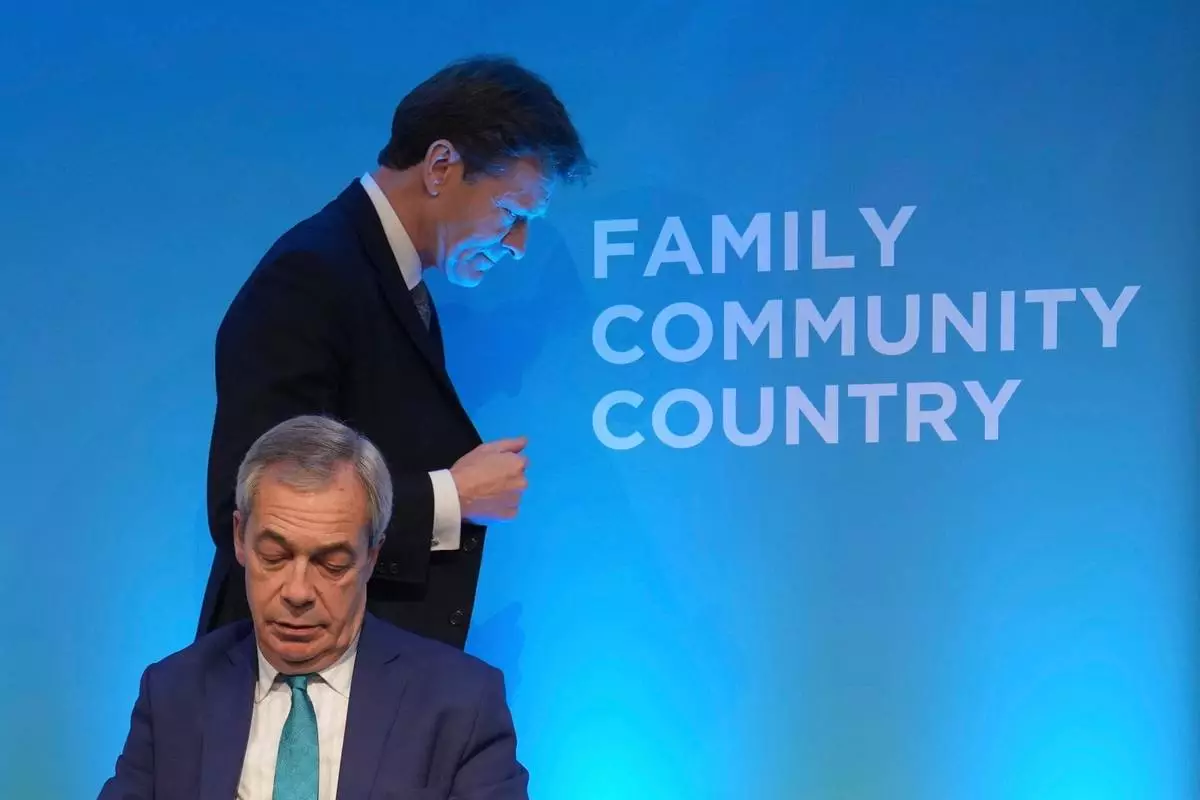

FILE - Reform UK leader Nigel Farage, front, and deputy leader Richard Tice attend a news conference on the economy and renewable energy, in London, Wednesday, Feb. 12, 2025. (AP Photo/Kin Cheung, File)

FILE - Protesters wave a Union Flag during a demonstration in Orpington near London, Friday, Aug. 22, 2025 as the dilemma of how to house asylum-seekers in Britain got more challenging for the government after a landmark court ruling this week motivated opponents to fight hotels used as accommodation. (AP Photo/Alberto Pezzali, File)