Federal traffic safety regulators are looking into suspected problems with Elon Musk's test run of self-driving “robotaxis” in Texas after videos surfaced showing them braking suddenly or going straight through an intersection from a turning lane and driving down the wrong side of the road.

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration said Tuesday that it has asked Tesla for information about the apparent errors. Though many other videos show robotaxis driving perfectly, if regulators find any major issues, that would likely raise questions about Musk's repeated statements that the robotaxis are safe and his claim that Tesla will dominate a future in which nearly all cars on road will have no one behind the wheel — or even need a steering wheel at all.

“NHTSA is aware of the referenced incidents and is in contact with the manufacturer to gather additional information,” the agency said in a statement.

Passengers in Tesla robotaxis on the road in Austin, Texas, have generally been impressed, and the stock rose 8% Monday. Investors grew more cautious Tuesday after news of NHTSA's inquiry, and the stock fell more than 2%.

Tesla did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

A bullish Tesla financial analyst who was driven around in a robotaxi on Sunday when the test runs began said his ride was perfect and suggested the videos on X and YouTube showing errors were no big deal.

“Any issues they encounter will be fixed,” said Wedbush Securities' Dan Ives, calling the test a “huge success" in the past three days “despite the skeptics.”

One of those skeptics, a Telemetry Insight expert in car technology, said the videos were alarming enough that the tests as currently run should be halted.

“The system has always had highly erratic performance, working really well a lot of the time but frequently making random and inconsistent but dangerous errors," said Sam Abuelsamid in a text, referring to Tesla's self-driving software. “This is not a system that should be carrying members of the public or being tested on public roads without trained test drivers behind the wheel.”

In one video, a Tesla moves into a lane with a big yellow arrow indicating it is for left turns only but then goes straight through the intersection instead, entering an opposing lane on the other side. The car seems to realize it made some mistake and begins to swerve several times, with the steering wheel jerking back and forth, before eventually settling down.

But the Tesla proceeds in the opposing lane for 10 seconds. At the time, there was no oncoming traffic.

The passenger in the car who posted the video, money manager Rob Maurer, shrugged off the incident.

“There are no vehicles anywhere in sight, so this wasn’t a safety issue,” Maurer said in commentary accompanying his video. “I didn’t feel uncomfortable in the situation.”

Another video shows a Tesla stopping twice suddenly in the middle of the road, possibly responding to the flashing lights of police cars. But the police are obviously not interested in the Tesla or traffic in front or behind it because they have parked on side roads not near it, apparently responding to an unrelated event.

Federal regulators opened an investigation last year into how Teslas with what Musk calls Full Self-Driving have responded in low-visibility conditions after several accidents, including one that was fatal. Tesla was forced a recall 2.4 million of its vehicles at the time.

Musk has said his Teslas using Full Self-Driving are safer than human drivers and his robotaxis using a newer, improved version of the system will be so successful so quickly that he will be able to deploy hundreds of thousands of them on the road by the end of next year.

Even if the Austin test goes well, though, the billionaire faces big challenges. Other self-driving companies have launched taxis, including Amazon's Zoox and current market leader Waymo, which is not only is picking up passengers in Austin, but several other cities. The company recently announced it had clocked its 10 millionth paid ride.

Musk needs a win in robotaxis. His work on in Trump administration as cost-cutting czar has alienated many buyers among Tesla's traditional environmentally conscious and liberal base in the U.S., tanking sales. Buyers in Europe having balked, too, after Musk embraced some extreme right-wing politicians earlier this year in both Britain and Germany.

A rider boards a driverless Tesla robotaxi, a ride-booking service, Sunday, June 22, 2025, in Austin, Texas. (AP Photo/Eric Gay)

A driverless Tesla robotaxi, a ride-booking service, moves through traffic, Sunday, June 22, 2025, in Austin, Texas. (AP Photo/Eric Gay)

JEFFERSONVILLE, Ind. (AP) — Inside a storage room at the Clark County Health Department are boxes with taped-on signs reading, “DO NOT USE.” They contain cookers and sterile water that people use to shoot up drugs.

The supplies, which came from the state and were paid for with federal money, were for a program where drug users exchange dirty needles for clean ones, part of a strategy known as harm reduction. But under a July executive order from President Donald Trump, federal substance abuse grants can’t pay for supplies such as cookers and tourniquets that it says “only facilitate illegal drug use.” Needles already couldn’t be purchased with federal money.

In some places, the order is galvanizing support for syringe exchange programs, which decades of research show are extremely effective at preventing disease among intravenous drug users and getting them into treatment.

In others, it’s fueling opposition that threatens the programs' existence.

Republican-led Indiana passed a law allowing exchanges a decade ago after the tiny city of Austin became the epicenter of the worst drug-fueled HIV outbreak in U.S. history. Unless lawmakers extend it, that law is scheduled to sunset next year, and the number of exchanges has been dwindling. State officials told remaining programs to comply with Trump's order — and even to discard federally funded supplies such as cookers and tourniquets.

For now, Clark County health workers have found a way to keep distributing cookers and other items: buy them with private money and package them in “mystery bags,” assembled by employees who aren’t paid with state or federal funds.

Democratic-led California, meanwhile, has continued using state funds for supplies such as pipes and syringes. California is home to a rising number of exchanges, with 70 of the more than 580 listed by the North American Syringe Exchange Network.

Some public health experts lament that syringe services programs have become subject to growing politicization and dissent.

Clark County Health Officer Dr. Eric Yazel says IV drug users will likely inject themselves with or without clean supplies. Exchanges prevent people from sharing needles and spreading disease, he said, “decreasing the public health risk for the whole population.”

But Curtis Hill, a Republican former Indiana attorney general, is among critics who raise the same concern Trump’s order does: “We don’t want to get into a situation where we’re promoting drug use.”

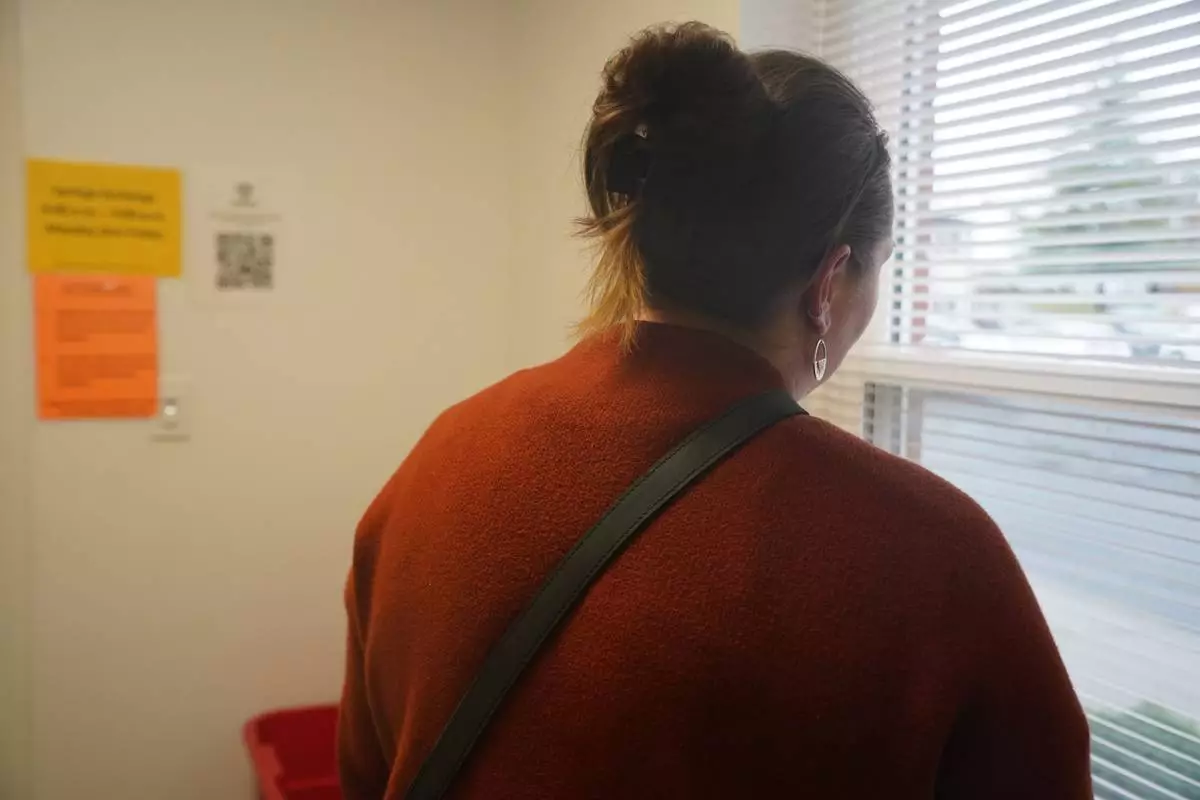

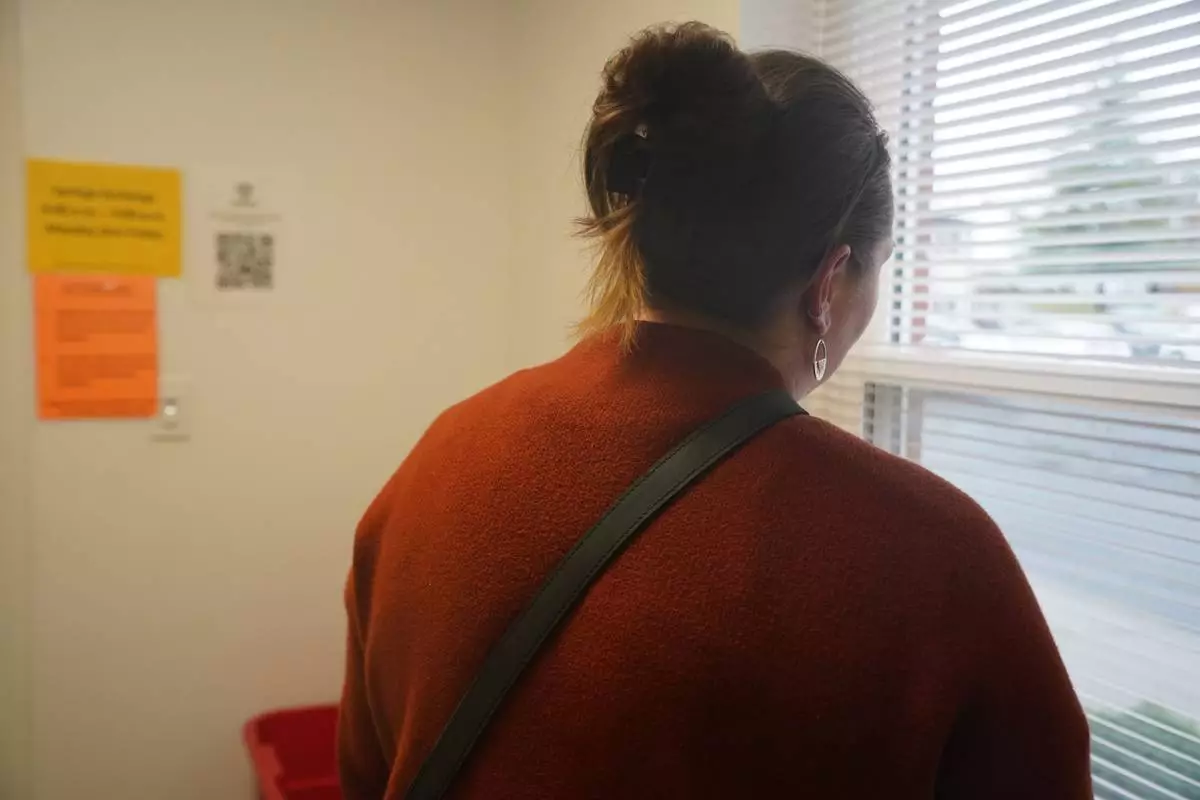

When participants arrive at the Clark County health department, they look down at a list of services and say they are there for “No. 1.”

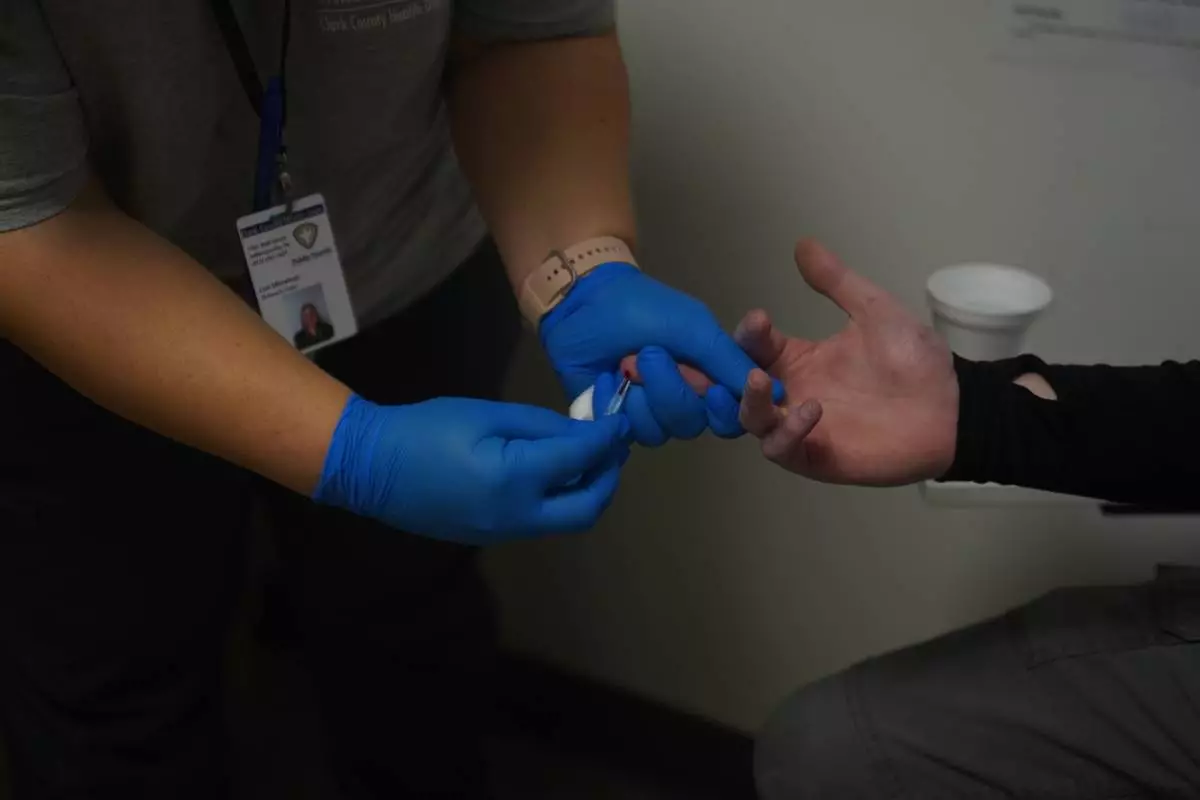

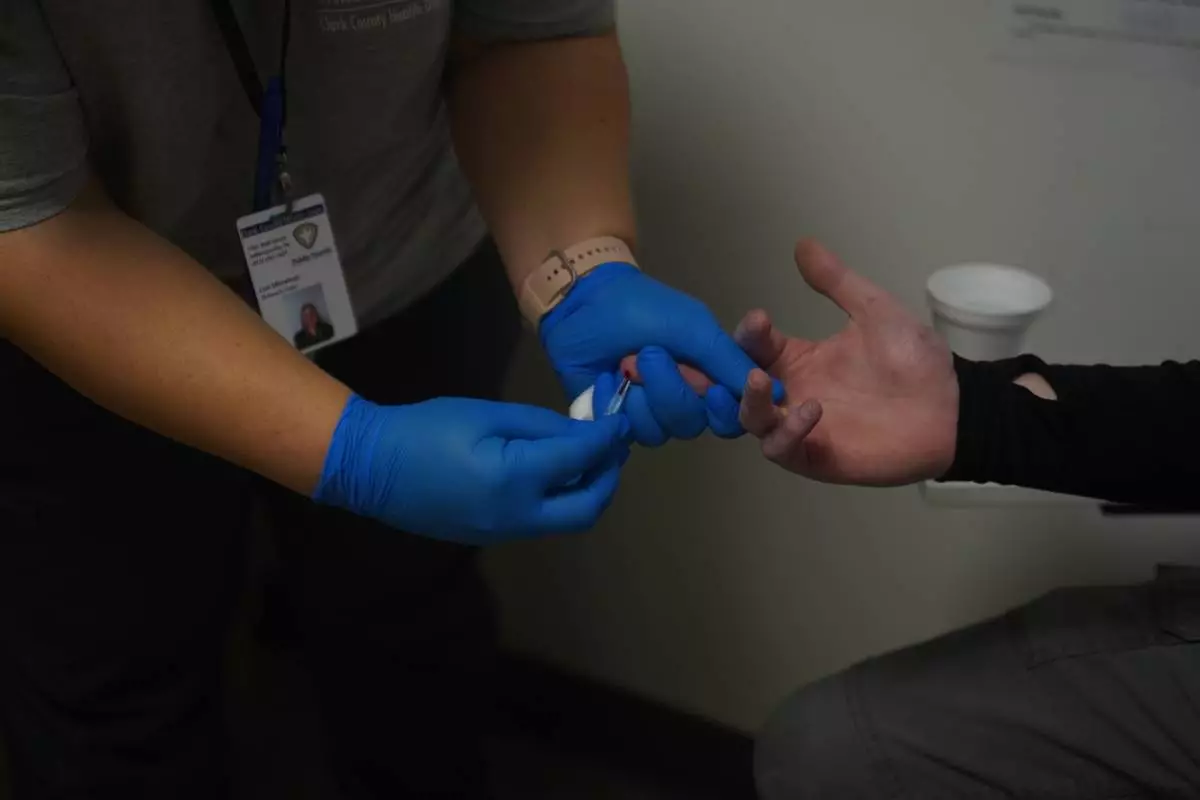

They choose from a cart with needles, bandages, sharps containers and the overdose reversal drug naloxone. They can receive testing for HIV and hepatitis C; information on drug treatment; and fliers on food banks, housing, and job placement. There are even handmade knit hats with encouraging notes like, “You’ve got this!”

“We spend a half hour, 45 minutes or so talking to them about where they are, if they want treatment, if they’re ready,” Program Director Dorothy Waterhouse said. “These are our brothers, our sisters, our mothers, our fathers. … We need compassion to make sure they’re getting into treatment.”

It's the closest exchange to Austin, a 35-minute drive away. Scott County, where Austin is located, already ended its program.

Joshua Gay lived in an apartment across the street when he used the Clark County exchange. He shot up meth daily.

“The addiction, it took away everything. It took away my life. It took away my job, took away my health. I mean, it made my mind so bad that I wouldn’t even shower,” said the 44-year-old, who now lives in Austin. “God was telling me, ‘You need to do something,’ and he led me to the needle exchange.”

He's sober today. He sought drug treatment at LifeSpring Health Systems after encouragement from health workers and now encourages others in recovery to stay healthy.

He believes the syringe exchange not only saved him, but helped him save someone else, providing the naloxone he used to revive a friend who overdosed on heroin.

After Trump's order — which focused on homelessness — Indiana health officials told exchanges that certain items they provided were now off-limits, citing a letter from the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Although Clark County workers have found ways to provide privately funded items for now, they worry about Indiana’s exchange law expiring on July 1. Six counties have exchanges — down from nine in 2020 — despite the programs’ successes.

Statewide, exchanges have made more than 27,000 referrals to drug treatment and provided naloxone that reversed nearly 25,000 overdoses, according to information collected by the nonprofit Damien Center in Indianapolis.

Since its 2017 start, Clark County’s program alone has given out more than 2,000 doses of naloxone; made more than 4,300 referrals to drug treatment; and made more than 4,400 referrals for HIV or hepatitis C testing. Its syringe return rate is 92%.

Local and national public health and addiction experts point to research showing exchanges don't increase syringe litter, crime or IV drug use — and that every dollar invested returns an estimated $7 in avoided health care costs.

Exchanges are associated with an estimated 50% reduction in the incidence of HIV and hepatitis C, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said last year. Scott County — where the HIV outbreak ultimately sickened 235 people — had fewer than five new cases a year in 2020 and 2021, just before that syringe program ended. The numbers have stayed low.

“When these programs first started, I was like, ‘I don’t know.’ I didn’t get it,” Yazel said. “And then I took a deep dive and started to understand the impact.”

Indiana is among 43 states with syringe services programs, according to health care research nonprofit KFF.

Support remains strong in many places. This year in Hawaii, for example, legislators passed a law allowing people to get as many clean needles as needed rather than only one for one.

But bills elsewhere, including two introduced in West Virginia this year, propose eliminating syringe programs.

This month, West Virginia's Cabell-Huntington Health Department stopped giving out needles. Naloxone and fentanyl test strips remain available, along with services such as education, disease testing and links to care.

“The folks who come in to see us are going to get the same smiles and the same hugs,” said Health Officer Dr. Michael Kilkenny. “We’re just not going to be dispensing syringes or the other things that are in disfavor.”

Andrew Nixon, spokesman for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, stressed in an email that federal funds can still be used for “life-saving services” like education and naloxone, reflecting a “commitment to addressing the addiction and overdose crisis impacting communities across our nation.”

Yazel expects a difficult path ahead in Indiana.

“To be very blunt,” he said, “we have an uphill battle coming up this legislative session.”

Damien Center CEO Alan Witchey, whose organization runs a syringe program, said he and a group of advocates created a website with information and a way to contact lawmakers. They've met with elected officials, and a state senator introduced a bill to extend the sunset date to 2036.

“Without these programs, there will be one less tool to address the diseases of substance use disorder, hepatitis C and HIV,” Witchey said. “And that could lead to a very dangerous place for us. We have seen where this leads.”

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Department of Science Education and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

A sharps disposal bin to safely discard used syringes and lancets is installed in Austin, Ind., by the Scott County Health Department Tuesday, Nov. 23, 2025. (AP Photo/Obed Lamy)

Joshua Gay, a former participant in the Clark County Health Department's syringe exchange program who is now in recovery from substance use disorder, poses for a portrait in front of his church Tuesday, Nov. 23, 2025, in Austin, Ind. (AP Photo/Obed Lamy)

A participant in the syringe exchange program receives a blood draw during a visit at the Clark County Health Department Tuesday, Nov. 23, 2025, in Jeffersonville, Ind. (AP Photo/Obed Lamy)

A participant in the syringe exchange program stands in an exam room at the Clark County Health Department Tuesday, Nov. 23, 2025, in Jeffersonville, Ind. (AP Photo/Obed Lamy)

Dorothy Waterhouse, program director for the syringe exchange program at the Clark County Health Department, opens a cabinet containing supplies used for the program Tuesday, Nov. 23, 2025, in Jeffersonville, Ind. (AP Photo/Obed Lamy)