SREBRENICA, Bosnia-Herzegovina (AP) — Three decades after their fathers, brothers, husbands and sons were killed in the bloodiest episode of the Bosnian war, women who survived the Srebrenica massacre find some solace in having been able to unearth their loved ones from far-away mass graves and bury them individually at the town's memorial cemetery.

The women say that living near the graves reminds them not only of the tragedy but of their love and perseverance in seeking justice for the men they lost.

Click to Gallery

Bosnian Muslim family watch people participating in the "March of Peace" in memory of the 1995 Srebrenica massacre, in Nezuk, Bosnia, Tuesday, July 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Armin Durgut)

Participants in the "March of Peace" march in memory of the 1995 Srebrenica massacre, in Nezuk, Bosnia, Tuesday, July 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Armin Durgut)

Nura Mustavic, 79, poses for a photo while holding pictures of her three sons and a husband, victims of the Srebrenica genocide in the village of Bajramovici near Srebrenica, Bosnia, on June 28, 2025. The body of one of her sons was never found. (AP Photo/Armin Durgut)

Suhra Malic, 89, mourns while looking at the pictures of her two sons, victims of the Srebrenica genocide, in a nursing home in the village of Potocari near Srebrenica, Bosnia, on June 29, 2025. During the genocide a total of 20 members of her family were killed. (AP Photo/Armin Durgut)

Sehida Abdurahmanovic, 74, poses for a photo while holding pictures of family members, victims of the Srebrenica genocide in village of Potocari near Srebrenica, Bosnia, on June 28, 2025. Body of her brother was never found. (AP Photo/Armin Durgut)

Saliha Osmanovic, 71, poses for a photo while holding pictures of her two sons and husband, victims of the Srebrenica genocide in the village of Dobrak near Srebrenica, Bosnia, on June 28, 2025. During the genocide a total of 38 members of her family were killed. (AP Photo/Armin Durgut)

An aerial view of the Srebrenica Genocide Memorial Center in Potocari, Bosnia, on June 28, 2025. (AP Photo/Armin Durgut)

“I found peace here, in the proximity of my loved ones," said Fadila Efendic, 74, who returned to her family home in 2002, seven years after being driven away from Srebrenica and witnessing her husband and son being taken away to be killed.

The Srebrenica killings were the crescendo of Bosnia’s 1992-95 war, which came after the breakup of Yugoslavia unleashed nationalist passions and territorial ambitions that set Bosnian Serbs against the country’s two other main ethnic populations — Croats and Bosniaks.

On July 11, 1995, Serbs overran Srebrenica, at the time a U.N.-protected safe area. They separated at least 8,000 Bosniak men and boys from their wives, mothers and sisters and slaughtered them. Those who tried to escape were chased through the woods and over the mountains around town.

Bosniak women and children were packed onto buses and expelled.

The executioners tried to erase the evidence of their crime, plowing the bodies into hastily dug mass graves and scattering them among other burial sites.

As soon as the war was over, Efendic and other women like her vowed to find their loved ones, bring them back and give them a proper burial.

“At home, often, especially at dusk, I imagine that they are still around, that they went out to go to work and that they will come back,” Efendic said, adding: “That idea, that they will return, that I am near them, is what keeps me going.”

To date, almost 90% of those reported missing since the Srebrenica massacre have been accounted for through their remains exhumed from hundreds of mass graves scattered around the eastern town. Body parts are still being found in death pits around Srebrenica and identified through painstaking DNA analysis.

So far, the remains of more than 6,700 people – including Efendic’s husband and son - have been found in several different mass graves and reburied at the memorial cemetery inaugurated in Srebrenica in 2003 at the relentless insistence of the women.

“We wrote history in white marble headstones and that is our success,” said Kada Hotic, who lost her husband, son and 56 other male relatives in the massacre. “Despite the fact that our hearts shiver when we speak about our sons, our husbands, our brothers, our people, our town, we refused to let (what happened to) them be forgotten.”

The Srebrenica carnage has been declared a genocide by two U.N. courts.

Dozens of Srebrenica women testified before the U.N. war crimes tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, helping put behind bars close to 50 Bosnian Serb wartime officials, collectively sentenced to over 700 years in prison.

After decades of fighting to keep the truth about Srebrenica alive, the women now spend their days looking at scarce mementos of their former lives, imagining the world that could have been.

Sehida Abdurahmanovic, who lost dozens of male relatives in the massacre, including her husband and her brother, often stares at a few family photos, two handwritten notes from her spouse and some personal documents she managed to take with her in 1995.

“I put these on the table to refresh my memories, to bring back to life what I used to have,” she said. “Since 1995, we have been struggling with what we survived and we can never, not even for a single day, be truly relaxed.”

Suhra Malic, 90, who lost two sons and 30 other male relatives, is also haunted by the memories.

“It is not a small feat to give birth to children, to raise them, see them get married and build them a house of their own and then, just as they move out and start a life of independence, you lose them, they are gone and there is nothing you can do about it,” Malic said.

Summers in Srebrenica are difficult, especially as July 11, the anniversary of the day the killing began in 1995, approaches.

In her own words, Mejra Djogaz “used to be a happy mother” to three sons, and now, “I look around myself and I am all alone, I have no one.”

“Not a single night or day goes by that I do not wake up at two or three after midnight and start thinking about how they died,” she said.

Aisa Omerovic agrees. Her husband, two sons and 42 other male relatives were killed in the massacre. Alone at home, she said she often hears the footsteps of her children and imagines them walking into the room. “I wait for the door to open; I know that it won’t open, but still, I wait.”

Bosnian Muslim family watch people participating in the "March of Peace" in memory of the 1995 Srebrenica massacre, in Nezuk, Bosnia, Tuesday, July 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Armin Durgut)

Participants in the "March of Peace" march in memory of the 1995 Srebrenica massacre, in Nezuk, Bosnia, Tuesday, July 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Armin Durgut)

Nura Mustavic, 79, poses for a photo while holding pictures of her three sons and a husband, victims of the Srebrenica genocide in the village of Bajramovici near Srebrenica, Bosnia, on June 28, 2025. The body of one of her sons was never found. (AP Photo/Armin Durgut)

Suhra Malic, 89, mourns while looking at the pictures of her two sons, victims of the Srebrenica genocide, in a nursing home in the village of Potocari near Srebrenica, Bosnia, on June 29, 2025. During the genocide a total of 20 members of her family were killed. (AP Photo/Armin Durgut)

Sehida Abdurahmanovic, 74, poses for a photo while holding pictures of family members, victims of the Srebrenica genocide in village of Potocari near Srebrenica, Bosnia, on June 28, 2025. Body of her brother was never found. (AP Photo/Armin Durgut)

Saliha Osmanovic, 71, poses for a photo while holding pictures of her two sons and husband, victims of the Srebrenica genocide in the village of Dobrak near Srebrenica, Bosnia, on June 28, 2025. During the genocide a total of 38 members of her family were killed. (AP Photo/Armin Durgut)

An aerial view of the Srebrenica Genocide Memorial Center in Potocari, Bosnia, on June 28, 2025. (AP Photo/Armin Durgut)

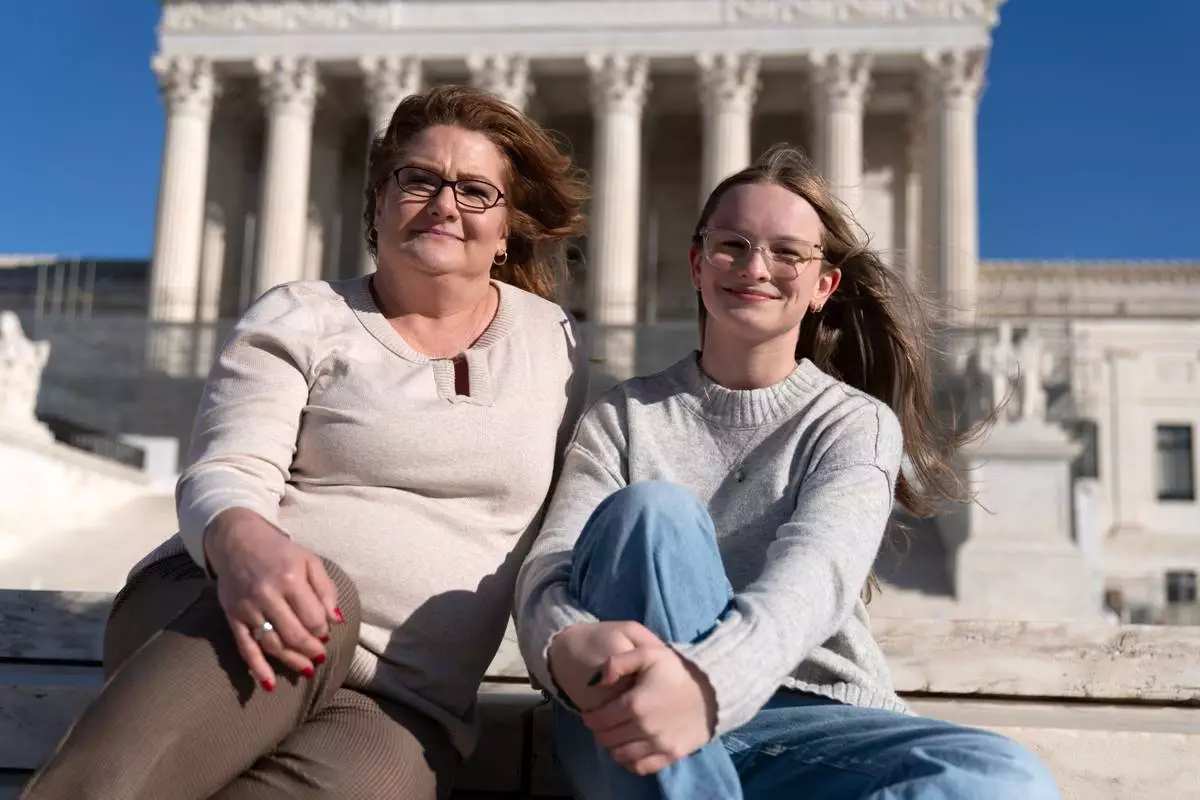

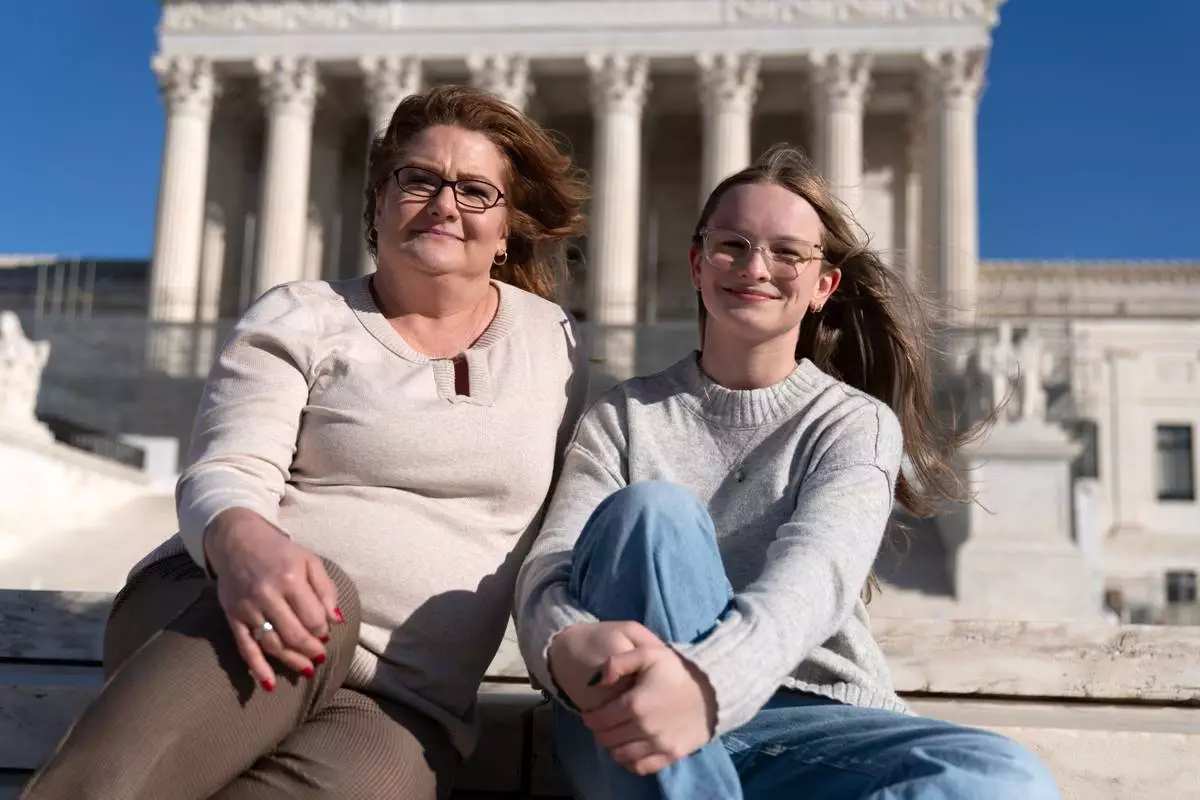

WASHINGTON (AP) — Becky Pepper-Jackson finished third in the discus throw in West Virginia last year though she was in just her first year of high school. Now a 15-year-old sophomore, Pepper-Jackson is aware that her upcoming season could be her last.

West Virginia has banned transgender girls like Pepper-Jackson from competing in girls and women's sports, and is among the more than two dozen states with similar laws. Though the West Virginia law has been blocked by lower courts, the outcome could be different at the conservative-dominated Supreme Court, which has allowed multiple restrictions on transgender people to be enforced in the past year.

The justices are hearing arguments Tuesday in two cases over whether the sports bans violate the Constitution or the landmark federal law known as Title IX that prohibits sex discrimination in education. The second case comes from Idaho, where college student Lindsay Hecox challenged that state's law.

Decisions are expected by early summer.

President Donald Trump's Republican administration has targeted transgender Americans from the first day of his second term, including ousting transgender people from the military and declaring that gender is immutable and determined at birth.

Pepper-Jackson has become the face of the nationwide battle over the participation of transgender girls in athletics that has played out at both the state and federal levels as Republicans have leveraged the issue as a fight for athletic fairness for women and girls.

“I think it’s something that needs to be done,” Pepper-Jackson said in an interview with The Associated Press that was conducted over Zoom. “It’s something I’m here to do because ... this is important to me. I know it’s important to other people. So, like, I’m here for it.”

She sat alongside her mother, Heather Jackson, on a sofa in their home just outside Bridgeport, a rural West Virginia community about 40 miles southwest of Morgantown, to talk about a legal fight that began when she was a middle schooler who finished near the back of the pack in cross-country races.

Pepper-Jackson has grown into a competitive discus and shot put thrower. In addition to the bronze medal in the discus, she finished eighth among shot putters.

She attributes her success to hard work, practicing at school and in her backyard, and lifting weights. Pepper-Jackson has been taking puberty-blocking medication and has publicly identified as a girl since she was in the third grade, though the Supreme Court's decision in June upholding state bans on gender-affirming medical treatment for minors has forced her to go out of state for care.

Her very improvement as an athlete has been cited as a reason she should not be allowed to compete against girls.

“There are immutable physical and biological characteristic differences between men and women that make men bigger, stronger, and faster than women. And if we allow biological males to play sports against biological females, those differences will erode the ability and the places for women in these sports which we have fought so hard for over the last 50 years,” West Virginia's attorney general, JB McCuskey, said in an AP interview. McCuskey said he is not aware of any other transgender athlete in the state who has competed or is trying to compete in girls or women’s sports.

Despite the small numbers of transgender athletes, the issue has taken on outsize importance. The NCAA and the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committees banned transgender women from women's sports after Trump signed an executive order aimed at barring their participation.

The public generally is supportive of the limits. An Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research poll conducted in October 2025 found that about 6 in 10 U.S. adults “strongly” or “somewhat” favored requiring transgender children and teenagers to only compete on sports teams that match the sex they were assigned at birth, not the gender they identify with, while about 2 in 10 were “strongly” or “somewhat” opposed and about one-quarter did not have an opinion.

About 2.1 million adults, or 0.8%, and 724,000 people age 13 to 17, or 3.3%, identify as transgender in the U.S., according to the Williams Institute at the UCLA School of Law.

Those allied with the administration on the issue paint it in broader terms than just sports, pointing to state laws, Trump administration policies and court rulings against transgender people.

"I think there are cultural, political, legal headwinds all supporting this notion that it’s just a lie that a man can be a woman," said John Bursch, a lawyer with the conservative Christian law firm Alliance Defending Freedom that has led the legal campaign against transgender people. “And if we want a society that respects women and girls, then we need to come to terms with that truth. And the sooner that we do that, the better it will be for women everywhere, whether that be in high school sports teams, high school locker rooms and showers, abused women’s shelters, women’s prisons.”

But Heather Jackson offered different terms to describe the effort to keep her daughter off West Virginia's playing fields.

“Hatred. It’s nothing but hatred,” she said. "This community is the community du jour. We have a long history of isolating marginalized parts of the community.”

Pepper-Jackson has seen some of the uglier side of the debate on display, including when a competitor wore a T-shirt at the championship meet that said, “Men Don't Belong in Women's Sports.”

“I wish these people would educate themselves. Just so they would know that I’m just there to have a good time. That’s it. But it just, it hurts sometimes, like, it gets to me sometimes, but I try to brush it off,” she said.

One schoolmate, identified as A.C. in court papers, said Pepper-Jackson has herself used graphic language in sexually bullying her teammates.

Asked whether she said any of what is alleged, Pepper-Jackson said, “I did not. And the school ruled that there was no evidence to prove that it was true.”

The legal fight will turn on whether the Constitution's equal protection clause or the Title IX anti-discrimination law protects transgender people.

The court ruled in 2020 that workplace discrimination against transgender people is sex discrimination, but refused to extend the logic of that decision to the case over health care for transgender minors.

The court has been deluged by dueling legal briefs from Republican- and Democratic-led states, members of Congress, athletes, doctors, scientists and scholars.

The outcome also could influence separate legal efforts seeking to bar transgender athletes in states that have continued to allow them to compete.

If Pepper-Jackson is forced to stop competing, she said she will still be able to lift weights and continue playing trumpet in the school concert and jazz bands.

“It will hurt a lot, and I know it will, but that’s what I’ll have to do,” she said.

Heather Jackson, left, and Becky Pepper-Jackson pose for a photograph outside of the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington, Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026. (AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana)

Heather Jackson, left, and Becky Pepper-Jackson pose for a photograph outside of the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington, Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026. (AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana)

Becky Pepper-Jackson poses for a photograph outside of the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington, Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026. (AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana)

The Supreme Court stands is Washington, Friday, Jan. 9, 2026. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

FILE - Protestors hold signs during a rally at the state capitol in Charleston, W.Va., on March 9, 2023. (AP Photo/Chris Jackson, file)