FLINT, Mich. (AP) — A procession of mothers wearing red sashes, pushing strollers and tending to toddlers made their way Friday to a little festival in Flint, Michigan, where families received diapers and kids played.

It was called a “baby parade.”

Click to Gallery

Seven-month-old twins Damonie and Dion Gill sit in a stroller together at the Flint Rx Kids Baby Parade event on July 25, 2025 in on Applewood Campus in Flint, Michigan. The event celebrates the continued impact of Rx Kids on Flint families and babies. (AP Photo/Emily Elconin)

Families and community members arrive for the Flint Rx Kids Baby Parade event on July 25, 2025 on the Applewood Campus in Flint, Michigan. The event celebrates the continued impact of Rx Kids on Flint families and babies. (AP Photo/Emily Elconin)

Trinity Wilson, 12, holds her five-month-old cousin, Jaylen, as she and her family walk around the Flint Rx Kids Baby Parade event on July 25, 2025 in on Applewood Campus in Flint, Michigan. The event celebrates the continued impact of Rx Kids on Flint families and babies. (AP Photo/Emily Elconin)

Dr. Mona Hanna, creator of the Flint Rx Kids program, at the Hurley's Children Clinic ahead of the Flint Rx Kids Baby Parade on July 25, 2025 in Flint, Mich. (AP Photo/Emily Elconin)

Caroline Doennez smiles as she holds up her nine-month-old daughter, Violet, during the Flint Rx Kids Baby Parade event on July 25, 2025 in on Applewood Campus in Flint, Michigan. The event celebrates the continued impact of Rx Kids on Flint families and babies. (AP Photo/Emily Elconin)

The sashes indicated the women were participants of a growing program in Michigan that helps pregnant women and new moms by giving them cash over the first year of their children's lives. Launched in 2024, the program comes at a time when many voters worry over high child care costs and President Donald Trump’s administration floats policy to reverse the declining birth rate.

Backed by a mix of state, local and philanthropic money, Rx Kids gives mothers of newborns up to $7,500, with no income requirements and no rules for how the money is spent. Supporters believe the program could be a model for mitigating the high cost of having children in the U.S.

“There’s all kinds of reasons, no matter what your political affiliation or ideology is, to support this,” said state Sen. John Damoose, a Republican and ardent supporter of the program.

To qualify, women need to prove they live in a participating location and that they are pregnant, but don’t have to share details about their income.

It's designed to be simple.

Pregnant women receive $1,500 before delivery and $500 every month for the first six to 12 months of their babies’ lives, depending on the program location.

Dr. Mona Hanna, a pediatrician, associate dean for public health at Michigan State University College of Human Medicine and the program's founding director, said that window is a time of great economic vulnerability for new parents — and a critical developmental period for babies.

Most participants need diapers, formula, breast feeding supplies and baby clothes but every family's needs are different. The monthly payment can also help buy food and cover rent, utilities and transportation.

For some moms, the extra cash allows them to afford child care and return to work. For others, it allows them to stay home longer.

The program so far is available in Flint, Pontiac, Kalamazoo and five counties in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. By fall, it will expand to a rural central Michigan county and several cities near Detroit.

Hanna said the main piece of feedback she hears is that the program should be bigger. She’s heard from lawmakers and others hoping to start similar programs in other states.

Hanna said the program's data shows nearly all pregnant women in Flint have signed up since it became available.

The locations were designed to target low-income families, though there is no income requirement. Luke Shaefer, a professor of public policy at the University of Michigan and a co-founder of Rx Kids, said they wanted to eliminate any stigma or barriers that discourage people from signing up.

The founders also want mothers to feel celebrated, hence the parade Friday.

“For so long moms have been vilified and not supported,” Hanna said.

Friends told Angela Sintery, 44, about Rx Kids when she found out she was pregnant with her second child. She's a preschool teacher who spread the word to other parents.

Sintery had her first daughter 19 years before her second and had to buy all new baby supplies.

She said the cash provided by Rx Kids would have been helpful when she had her first child at age 24, before she went to college.

“So this time around, I didn’t have to stress about anything. I just had to worry about my baby,” she said.

Celeste Lord-Timlin, a Flint resident and program participant, attended the baby parade with her husband and 13-month-old daughter by her side. She said the deposits helped her pay for graduate school while she was pregnant.

“It allowed us to really enjoy being new parents," she said.

The program relies heavily on philanthropic donations but Hanna’s long-term goal is for the government to be the main provider.

“I see philanthropy as the doula of this program, they are helping birth it,” she said. “They are helping us prove that this is possible.”

Democrats in Michigan's state Senate introduced legislation in February that would make the program available to any pregnant woman in the state and it has bipartisan support. But with a divided Legislature only able to pass six bills total this year, it's unlikely the program will yet expand statewide soon.

Even Damoose, among the program's top backers, said he doesn't think Michigan can afford statewide expansion yet. But the lawmaker who represents parts of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan does want to keep growing it.

For fellow Republicans who oppose abortion as he does, the approach is a “no brainer” way to help pregnant women, Damoose said.

“We’ve been accused for years and years, and not without cause, of being pro-birth, but not pro-life,” he said. “And this is a way for us to put our money where our mouth is.”

A new movement of pro-natalist political figures, including Vice President JD Vance, Elon Musk and other members of Trump's periphery, have harped on the country's declining birth rate.

But a recent Associated Press-NORC poll found that most Americans want the government to focus on the high costs of child care — not just the number of babies being born here.

Under Trump’s tax and spending bill that Congress passed in July, the child tax credit is boosted from $2,000 child tax credit to $2,200. But millions of families at lower income levels will not get the full credit.

The bill will also create a new children’s saving program, called Trump Accounts, with a potential $1,000 deposit from the Treasury.

That’s not available until children grow up and is more focused on building wealth rather than immediate relief, Hanna said.

“We don’t have that social infrastructure to invest in our families,” Hanna said. “No wonder people aren’t having children and our birth rates are going down.”

The Trump administration has also toyed with the idea of giving families one-time $5,000 “baby bonuses,” a policy similar to Rx Kids.

Critics have rightly pointed out that doesn't come close to covering the cost of child care or other expenses. Defenders of a cash-in-hand approach, though, say any amount can help in those critical early months.

“I think it’s part of a new narrative or the rekindling of an old narrative where we start to celebrate children and families,” said Damoose.

Associated Press writer Mike Householder contributed to this report.

The Associated Press’ women in the workforce and state government coverage receives financial support from Pivotal Ventures. The AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Seven-month-old twins Damonie and Dion Gill sit in a stroller together at the Flint Rx Kids Baby Parade event on July 25, 2025 in on Applewood Campus in Flint, Michigan. The event celebrates the continued impact of Rx Kids on Flint families and babies. (AP Photo/Emily Elconin)

Families and community members arrive for the Flint Rx Kids Baby Parade event on July 25, 2025 on the Applewood Campus in Flint, Michigan. The event celebrates the continued impact of Rx Kids on Flint families and babies. (AP Photo/Emily Elconin)

Trinity Wilson, 12, holds her five-month-old cousin, Jaylen, as she and her family walk around the Flint Rx Kids Baby Parade event on July 25, 2025 in on Applewood Campus in Flint, Michigan. The event celebrates the continued impact of Rx Kids on Flint families and babies. (AP Photo/Emily Elconin)

Dr. Mona Hanna, creator of the Flint Rx Kids program, at the Hurley's Children Clinic ahead of the Flint Rx Kids Baby Parade on July 25, 2025 in Flint, Mich. (AP Photo/Emily Elconin)

Caroline Doennez smiles as she holds up her nine-month-old daughter, Violet, during the Flint Rx Kids Baby Parade event on July 25, 2025 in on Applewood Campus in Flint, Michigan. The event celebrates the continued impact of Rx Kids on Flint families and babies. (AP Photo/Emily Elconin)

PARIS (AP) — Brigitte Bardot, the French 1960s sex symbol who became one of the greatest screen sirens of the 20th century and later a militant animal rights activist and far-right supporter, has died. She was 91.

Bardot died Sunday at her home in southern France, according to Bruno Jacquelin, of the Brigitte Bardot Foundation for the protection of animals. Speaking to The Associated Press, he gave no cause of death, and said no arrangements have yet been made for funeral or memorial services. She had been hospitalized last month.

Bardot became an international celebrity as a sexualized teen bride in the 1956 movie “And God Created Woman.” Directed by her then-husband, Roger Vadim, it triggered a scandal with scenes of the long-legged beauty dancing on tables naked.

At the height of a cinema career that spanned some 28 films and three marriages, Bardot came to symbolize a nation bursting out of bourgeois respectability. Her tousled, blond hair, voluptuous figure and pouty irreverence made her one of France’s best-known stars.

Such was her widespread appeal that in 1969 her features were chosen to be the model for “Marianne,” the national emblem of France and the official Gallic seal. Bardot’s face appeared on statues, postage stamps and even on coins.

‘’We are mourning a legend,'' French President Emmanuel Macron wrote Sunday on X.

Bardot’s second career as an animal rights activist was equally sensational. She traveled to the Arctic to blow the whistle on the slaughter of baby seals; she condemned the use of animals in laboratory experiments; and she opposed Muslim slaughter rituals.

“Man is an insatiable predator,” Bardot told The Associated Press on her 73rd birthday, in 2007. “I don’t care about my past glory. That means nothing in the face of an animal that suffers, since it has no power, no words to defend itself.”

Her activism earned her compatriots’ respect and, in 1985, she was awarded the Legion of Honor, the nation’s highest recognition.

Later, however, she fell from public grace as her animal protection diatribes took on a decidedly extremist tone. She frequently decried the influx of immigrants into France, especially Muslims.

She was convicted and fined five times in French courts of inciting racial hatred, in incidents inspired by her opposition to the Muslim practice of slaughtering sheep during annual religious holidays.

Bardot’s 1992 marriage to fourth husband Bernard d’Ormale, a onetime adviser to National Front leader Jean-Marie Le Pen, contributed to her political shift. She described Le Pen, an outspoken nationalist with multiple racism convictions of his own, as a “lovely, intelligent man.”

In 2012, she wrote a letter in support of the presidential bid of Marine Le Pen, who now leads her father's renamed National Rally party. Le Pen paid homage Sunday to an “exceptional woman” who was “incredibly French.”

In 2018, at the height of the #MeToo movement, Bardot said in an interview that most actors protesting sexual harassment in the film industry were “hypocritical” and “ridiculous” because many played “the teases” with producers to land parts.

She said she had never had been a victim of sexual harassment and found it “charming to be told that I was beautiful or that I had a nice little ass.”

Brigitte Anne-Marie Bardot was born Sept. 28, 1934, to a wealthy industrialist. A shy, secretive child, she studied classical ballet and was discovered by a family friend who put her on the cover of Elle magazine at age 14.

Bardot once described her childhood as “difficult” and said her father was a strict disciplinarian who would sometimes punish her with a horse whip.

But it was French movie producer Vadim, whom she married in 1952, who saw her potential and wrote “And God Created Woman” to showcase her provocative sensuality, an explosive cocktail of childlike innocence and raw sexuality.

The film, which portrayed Bardot as a bored newlywed who beds her brother-in-law, had a decisive influence on New Wave directors Jean-Luc Godard and Francois Truffaut, and came to embody the hedonism and sexual freedom of the 1960s.

The film was a box-office hit, and it made Bardot a superstar. Her girlish pout, tiny waist and generous bust were often more appreciated than her talent.

“It’s an embarrassment to have acted so badly,” Bardot said of her early films. “I suffered a lot in the beginning. I was really treated like someone less than nothing.”

Bardot’s unabashed, off-screen love affair with co-star Jean-Louis Trintignant further shocked the nation. It eradicated the boundaries between her public and private life and turned her into a hot prize for paparazzi.

Bardot never adjusted to the limelight. She blamed the constant press attention for the suicide attempt that followed 10 months after the birth of her only child, Nicolas. Photographers had broken into her house two weeks before she gave birth to snap a picture of her pregnant.

Nicolas’ father was Jacques Charrier, a French actor whom she married in 1959 but who never felt comfortable in his role as Monsieur Bardot. Bardot soon gave up her son to his father, and later said she had been chronically depressed and unready for the duties of being a mother.

“I was looking for roots then,” she said in an interview. “I had none to offer.”

In her 1996 autobiography “Initiales B.B.,” she likened her pregnancy to “a tumor growing inside me,” and described Charrier as “temperamental and abusive.”

Bardot married her third husband, West German millionaire playboy Gunther Sachs, in 1966, but the relationship again ended in divorce three years later.

Among her films were “A Parisian” (1957); “In Case of Misfortune,” in which she starred in 1958 with screen legend Jean Gabin; “The Truth” (1960); “Private Life” (1962); “A Ravishing Idiot” (1964); “Shalako” (1968); “Women” (1969); “The Bear And The Doll” (1970); “Rum Boulevard” (1971); and “Don Juan” (1973).

With the exception of 1963’s critically acclaimed “Contempt,” directed by Godard, Bardot’s films were rarely complicated by plots. Often they were vehicles to display Bardot in scanty dresses or frolicking nude in the sun.

“It was never a great passion of mine,” she said of filmmaking. “And it can be deadly sometimes. Marilyn (Monroe) perished because of it.”

Bardot retired to her Riviera villa in St. Tropez at the age of 39 in 1973 after “The Woman Grabber.”

She emerged a decade later with a new persona: An animal rights lobbyist, her face was wrinkled and her voice was deep following years of heavy smoking. She abandoned her jet-set life and sold off movie memorabilia and jewelry to create a foundation devoted exclusively to the prevention of animal cruelty.

Her activism knew no borders. She urged South Korea to ban the sale of dog meat and once wrote to U.S. President Bill Clinton asking why the U.S. Navy recaptured two dolphins it had released into the wild.

She attacked centuries-old French and Italian sporting traditions including the Palio, a free-for-all horse race, and campaigned on behalf of wolves, rabbits, kittens and turtle doves.

“It’s true that sometimes I get carried away, but when I see how slowly things move forward ... my distress takes over,” Bardot told the AP when asked about her racial hatred convictions and opposition to Muslim ritual slaughter,

In 1997, several towns removed Bardot-inspired statues of Marianne after the actress voiced anti-immigrant sentiment. Also that year, she received death threats after calling for a ban on the sale of horse meat.

Bardot once said that she identified with the animals that she was trying to save.

“I can understand hunted animals because of the way I was treated,” Bardot said. “What happened to me was inhuman. I was constantly surrounded by the world press.”

Ganley contributed to this story before her retirement. Angela Charlton in Paris contributed to this report.

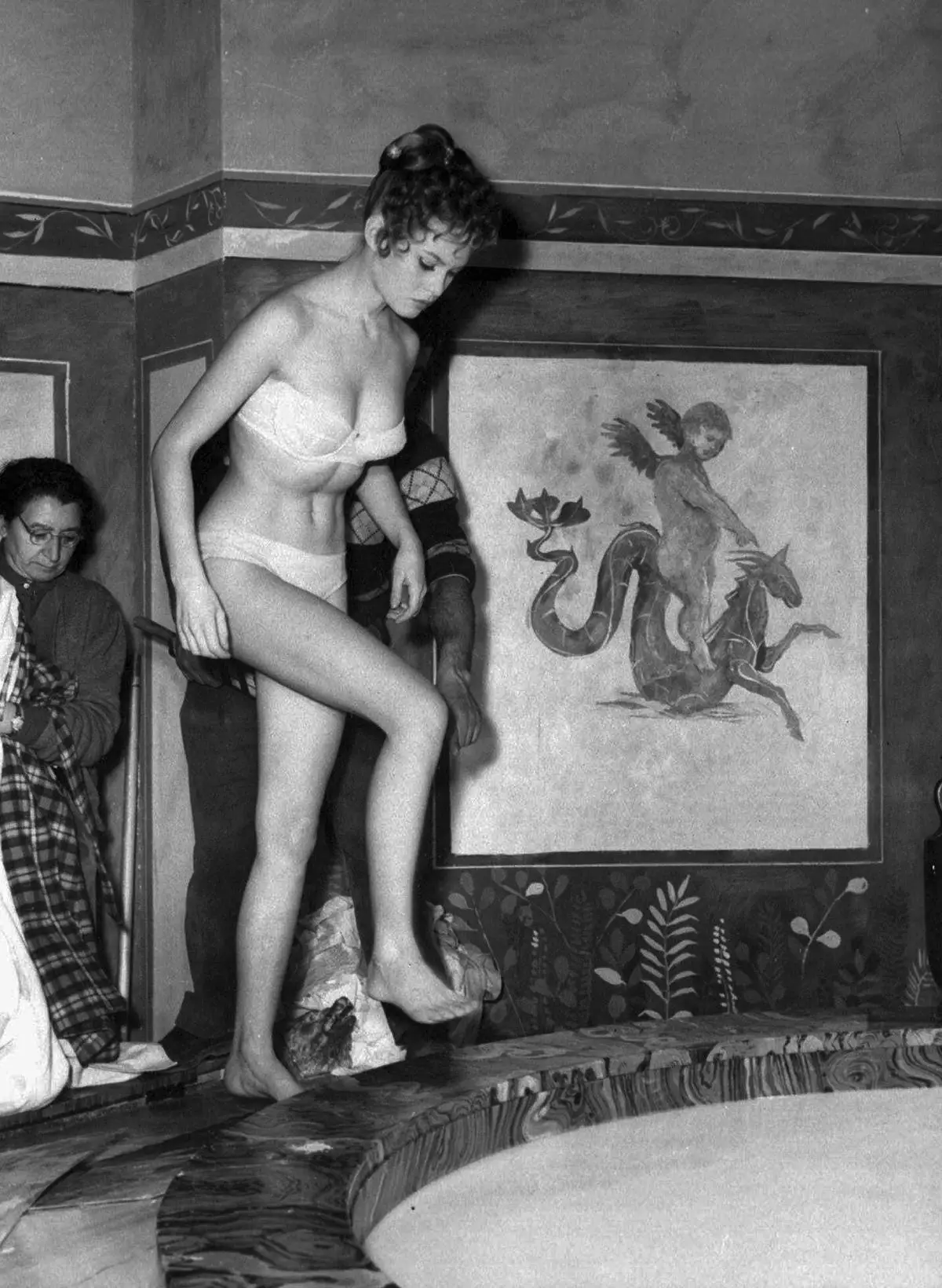

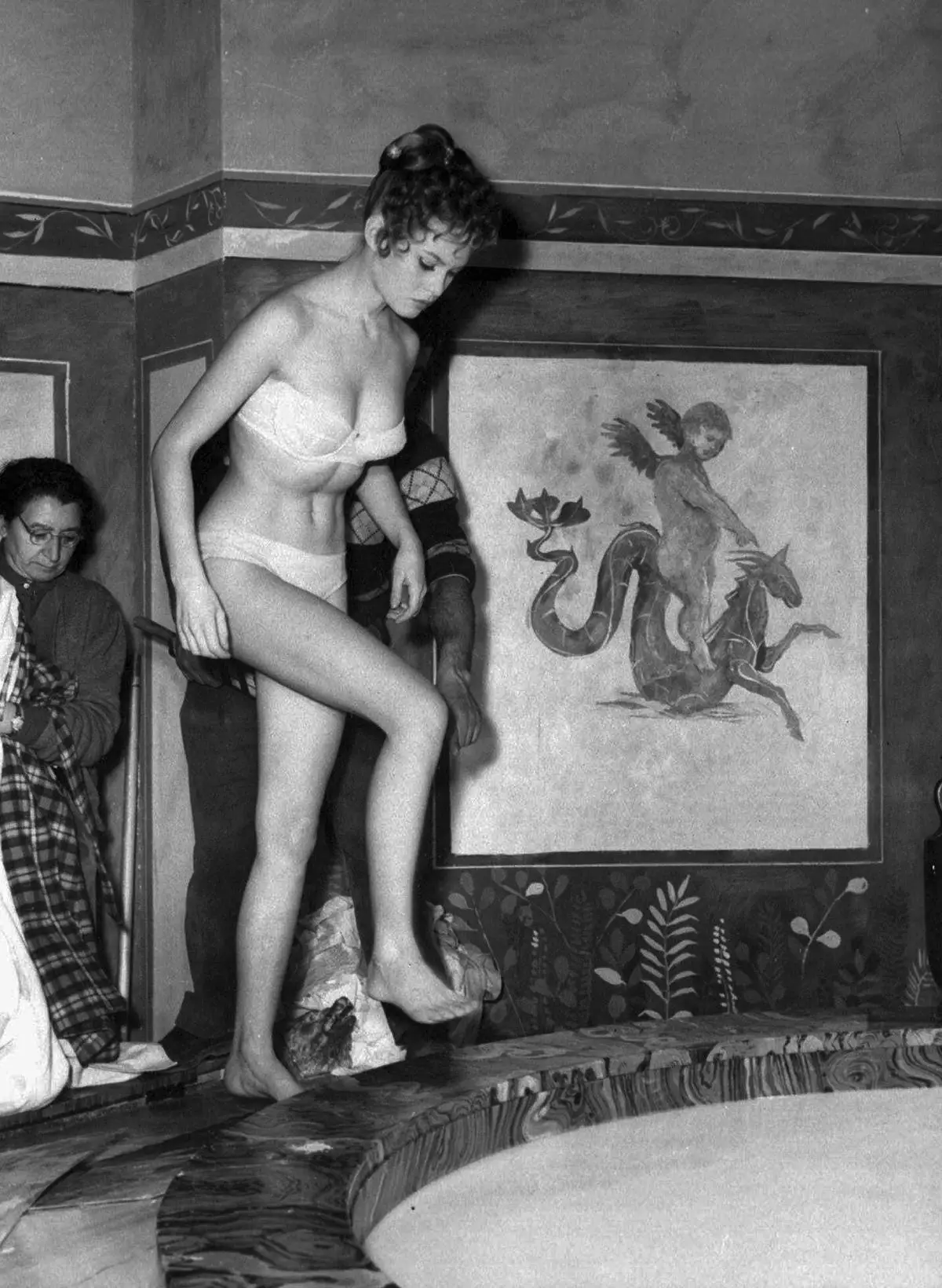

FILE - French actress Brigitte Bardot steps into a milk bath while filming the comedy "Nero's Big Weekend," in Rome March 27, 1956. (AP Photo/File)

FILE - French Actress Brigitte Bardot with a dog in the Gennevilliers, Paris, while supporting the French animal protection society operation, Feb. 10, 1982. (AP Photo/Duclos, File)

FILE - French actress Brigitte Bardot poses in character from the motion picture "Voulez-Vous Danser Avec Moi" (Do you Want to Dance With Me), on Sept. 10, 1959. (AP Photo/File)

FILE - French film legend and animal rights activist Brigitte Bardot looks on prior to a march of various animal rights associations on March 24, 2007 in Paris. (AP Photo/Jacques Brinon, file)

FILE - French actress Brigitte Bardot poses with a huge sombrero she brought back from Mexico, as she arrives at Orly Airport in Paris, France, on May 27, 1965. (AP Photo/File)