His rookie year on the PGA Tour was challenging enough for Jacob Bridgeman.

He got in 20 tournaments, none of them majors or The Players Championship, $20 million signature events or the FedEx Cup playoffs. He played seven times in the fall and did just well enough to keep his heart rate down and his ranking inside the top 125 to keep his card.

And then the PGA Tour approved a plan during the final week of 2024 to reduce the number of players keeping their cards to 100.

Gulp.

“I think it makes it tougher and tougher on the rookies,” Bridgeman said. “I feel like my rookie year was really hard, and this one was probably harder because there were less cards."

Bridgeman said he was neutral toward the change. The purpose was to make sure anyone who had a card could get into enough tournaments, and smaller fields in 2026 would keep rounds from not finishing because of darkness. And yes, it would be more competitive than ever.

Camilo Villegas was chairman of Player Advisory Council that proposed the changes and acknowledged it would be harder to keep a card. “But if we perform, there's an opportunity to make an unbelievable living," Villegas said.

Bridgeman performed.

He spoke Monday evening from Memphis, Tennessee, the first of three playoff events that determine the FedEx Cup champion. Bridgeman is No. 33 in the FedEx Cup, all but assured of staying in the top 50 to advance to the BMW Championship that will get him in all eight of the $20 million signature events next year.

The ultimate goal — East Lake for the Tour Championship — is well within range.

He is among 21 players at the TPC Southwind who did not make it to the postseason a year ago, all of them earning their way into the top 70.

Bridgeman began his sophomore season without assurances of being in any of the majors or the signature events.

He closed with a 64 at the Cognizant Classic for a runner-up finish, getting him into Bay Hill and The Players Championship. He slept on the lead the opening three rounds at the Valspar Championship and finished third, getting him into another signature event at the RBC Heritage.

He was among the last three players off the FedEx Cup to fill the field at the Truist Championship and tied for fourth, and his standing also got him into the U.S. Open.

Bridgeman wound up playing five signature events, two majors and The Players. He felt it was a disadvantage at the start. It turned into a big year that isn't over just yet.

“Not being in those at the beginning of the year was tough,” Bridgeman said. ”I went through that last year. I knew how that was and played past all that and still kept my card. I felt like it was a disadvantage, for sure, but not that it was unattainable.

“I just knew if I played well I'd have a chance," he said. “That was one my goals is playing a signature event early. I got in the Arnold Palmer and rode the wave all the way through.”

That's how it has been for the 25-year-old Bridgeman. He was No. 2 in the PGA Tour University his senior year at Clemson, which got him Korn Ferry Tour status. He spent 2023 on the developmental circuit and graduated to the PGA Tour.

Bridgeman wrote down his goals for 2025, big and small, in a journal. The main goal was to win. He's still waiting on that. He wanted at least four top 10s (check), make it to the FedEx Cup playoffs (check), get into the top 50 (one week away from another check) and get to East Lake for the Tour Championship.

“It's been nice to be able to check some of them off,” he said.

Being in all the signature events is an advantage, but not a guarantee. Fourteen players who finished in the top 50 last year failed to make it to the postseason, three of them because of injury — Billy Horschel, Will Zalatoris and Alex Noren.

Three players who were not among the top 50 last year — U.S. Open champion J.J. Spaun, Harris English and Ben Griffin — start the postseason in the top 10.

The turnover rate for those who qualified for the FedEx Cup playoffs was at 30% — 21 players finished in the top 70 who weren't in Memphis last year. That list includes multiple winners (Ryan Fox and Brian Campbell), first-time winners (Ryan Gerard and Chris Gotterup), and veterans who got their games headed in the right direction (Rickie Fowler and Lucas Glover).

And then there's players like Bridgeman, Sam Stevens and Michael Kim, who started with nothing more than a card and now have realistic hopes of East Lake.

The signature events were a source of consternation when they were first introduced, mainly the uncertainty of a level playing field. J.T. Poston said it best at the start of 2023, and it still rings true today.

“As long as there’s a way you still have to perform to stay in, and there’s an avenue for guys who aren’t in to play their way in, I don’t think there’s an issue,” Poston said.

Turns out it wasn't for Bridgeman.

On The Fringe analyzes the biggest topics in golf during the season.

AP golf: https://apnews.com/hub/golf

FILE = Jacob Bridgeman tees off on the 13th hole during the first round of the U.S. Open golf tournament at Oakmont Country Club Thursday, June 12, 2025, in Oakmont, Pa. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster,File)

FILE - Jacob Bridgeman hits from the third fairway during the final round of the Arnold Palmer Invitational at Bay Hill golf tournament, Sunday, March 9, 2025, in Orlando, Fla. (AP Photo/Phelan M. Ebenhack,File)

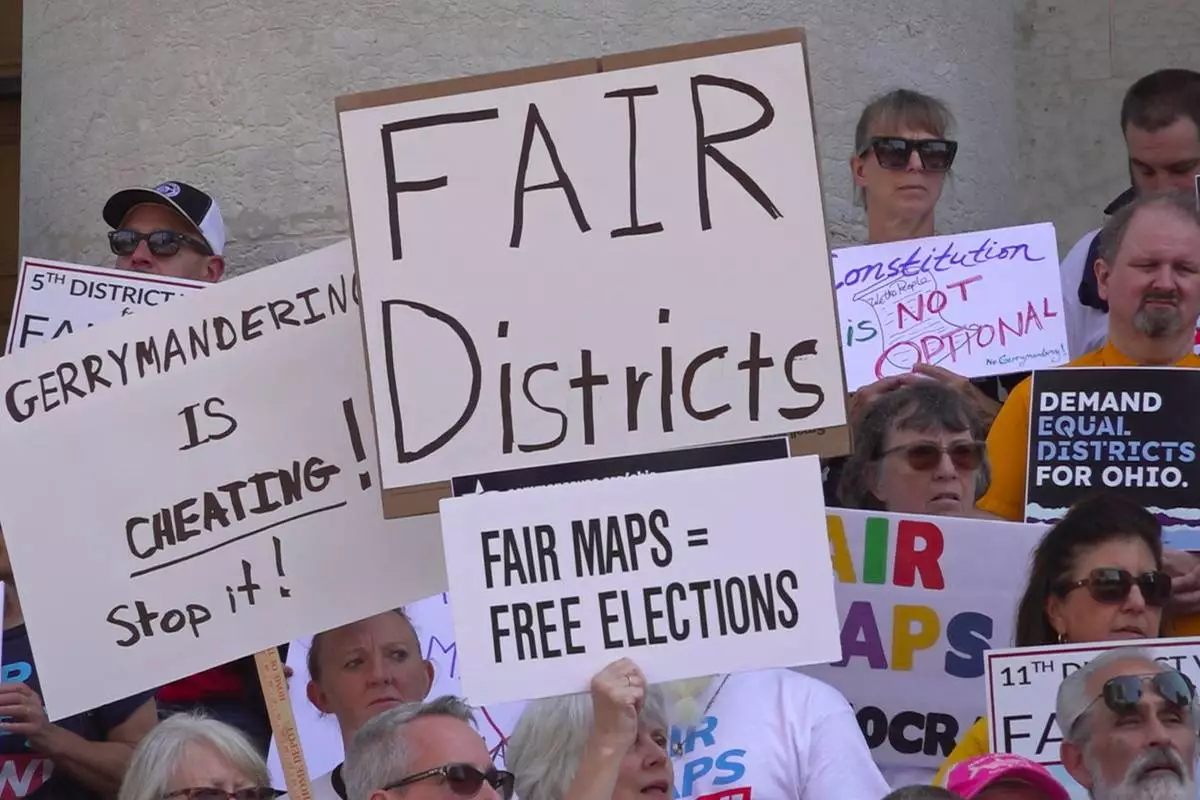

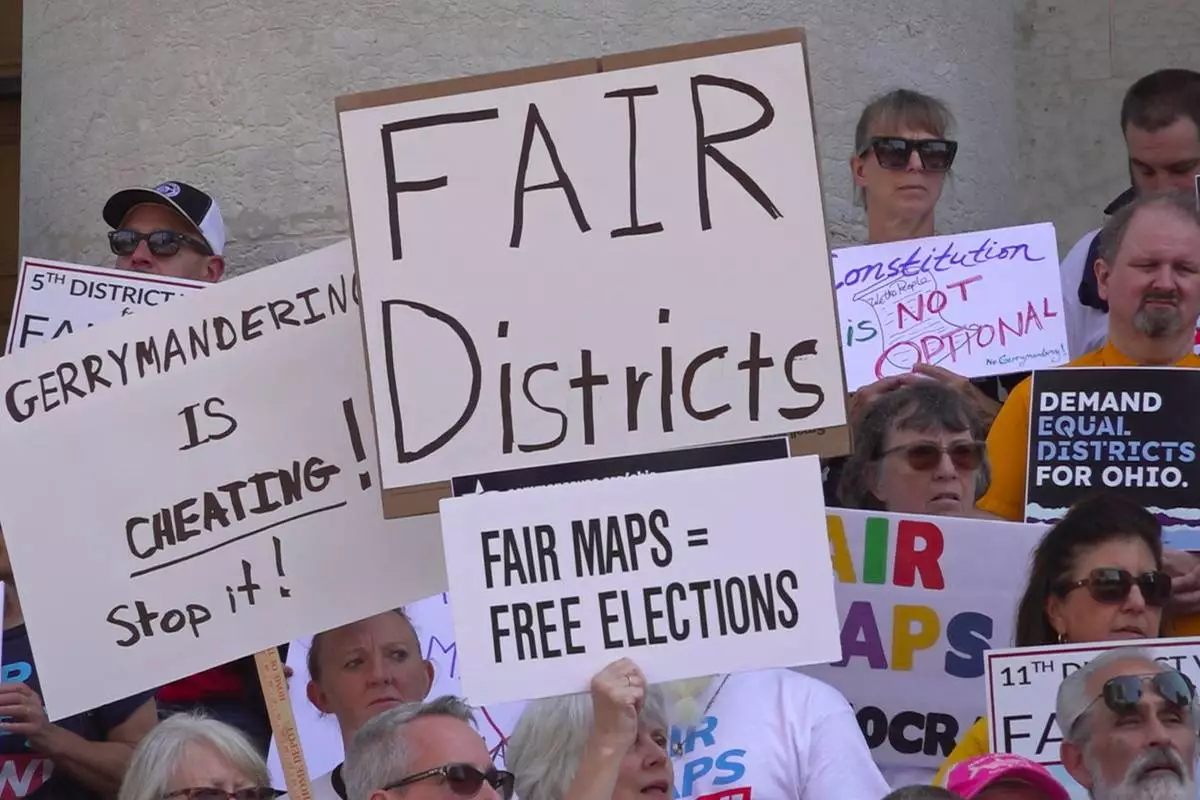

When Indiana adopted new U.S. House districts four years ago, Republican legislative leaders lauded them as “fair maps” that reflected the state's communities.

But when Gov. Mike Braun recently tried to redraw the lines to help Republicans gain more power, he implored lawmakers to "vote for fair maps.”

What changed? The definition of “fair.”

As states undertake mid-decade redistricting instigated by President Donald Trump, Republicans and Democrats are using a tit-for-tat definition of fairness to justify districts that split communities in an attempt to send politically lopsided delegations to Congress. It is fair, they argue, because other states have done the same. And it is necessary, they claim, to maintain a partisan balance in the House of Representatives that resembles the national political divide.

This new vision for drawing congressional maps is creating a winner-take-all scenario that treats the House, traditionally a more diverse patchwork of politicians, like the Senate, where members reflect a state's majority party. The result could be reduced power for minority communities, less attention to certain issues and fewer distinct voices heard in Washington.

Although Indiana state senators rejected a new map backed by Trump and Braun that could have helped Republicans win all nine of the state’s congressional seats, districts have already been redrawn in Texas, California, Missouri, North Carolina and Ohio. Other states could consider changes before the 2026 midterms that will determine control of Congress.

“It’s a fundamental undermining of a key democratic condition,” said Wayne Fields, a retired English professor from Washington University in St. Louis who is an expert on political rhetoric.

“The House is supposed to represent the people,” Fields added. “We gain an awful lot by having particular parts of the population heard.”

Under the Constitution, the Senate has two members from each state. The House has 435 seats divided among states based on population, with each state guaranteed at least one representative. In the current Congress, California has the most at 52, followed by Texas with 38.

Because senators are elected statewide, they are almost always political pairs of one party or another. Pennsylvania and Wisconsin are the only states now with both a Democrat and Republican in the Senate. Maine and Vermont each have one independent and one senator affiliated with a political party.

By contrast, most states elect a mixture of Democrats and Republicans to the House. That is because House districts, with an average of 761,000 residents, based on the 2020 census, are more likely to reflect the varying partisan preferences of urban or rural voters, as well as different racial, ethnic and economic groups.

This year's redistricting is diminishing those locally unique districts.

In California, voters in several rural counties that backed Trump were separated from similar rural areas and attached to a reshaped congressional district containing liberal coastal communities. In Missouri, Democratic-leaning voters in Kansas City were split from one main congressional district into three, with each revised district stretching deep into rural Republican areas.

Some residents complained their voices are getting drowned out. But Govs. Gavin Newsom, D-Calif., and Mike Kehoe, R-Mo., defended the gerrymandering as a means of countering other states and amplifying the voices of those aligned with the state's majority.

Indiana's delegation in the U.S. House consists of seven Republicans and two Democrats — one representing Indianapolis and the other a suburban Chicago district in the state's northwestern corner.

Dueling definitions of fairness were on display at the Indiana Capitol as lawmakers considered a Trump-backed redistricting plan that would have split Indianapolis among four Republican-leaning districts and merged the Chicago suburbs with rural Republican areas. Opponents walked the halls in protest, carrying signs such as “I stand for fair maps!”

Ethan Hatcher, a talk radio host who said he votes for Republicans and Libertarians, denounced the redistricting plan as “a blatant power grab" that "compromises the principles of our Founding Fathers" by fracturing Democratic strongholds to dilute the voices of urban voters.

“It’s a calculated assault on fair representation," Hatcher told a state Senate committee.

But others asserted it would be fair for Indiana Republicans to hold all of those House seats, because Trump won the “solidly Republican state” by nearly three-fifths of the vote.

“Our current 7-2 congressional delegation doesn’t fully capture that strength,” resident Tracy Kissel said at a committee hearing. "We can create fairer, more competitive districts that align with how Hoosiers vote.”

When senators defeated a map designed to deliver a 9-0 congressional delegation for Republicans, Braun bemoaned that they had missed an “opportunity to protect Hoosiers with fair maps.”

By some national measurements, the U.S. House already is politically fair. The 220-215 majority that Republicans won over Democrats in the 2024 elections almost perfectly aligns with the share of the vote the two parties received in districts across the country, according to an Associated Press analysis.

But that overall balance belies an imbalance that exists in many states. Even before this year's redistricting, the number of states with congressional districts tilted toward one party or another was higher than at any point in at least a decade, the AP analysis found.

The partisan divisions have contributed to a “cutthroat political environment” that “drives the parties to extreme measures," said Kent Syler, a political science professor at Middle Tennessee State University. He noted that Republicans hold 88% of congressional seats in Tennessee, and Democrats have an equivalent in Maryland.

“Fairer redistricting would give people more of a feeling that they have a voice," Syler said.

Rebekah Caruthers, who leads the Fair Elections Center, a nonprofit voting rights group, said there should be compact districts that allow communities of interest to elect the representatives of their choice, regardless of how that affects the national political balance. Gerrymandering districts to be dominated by a single party results in “an unfair disenfranchisement" of some voters, she said.

“Ultimately, this isn’t going to be good for democracy," Caruthers said. "We need some type of détente.”

A protester celebrates as they walk outside the Indiana Senate Chamber after a bill to redistrict the state's congressional map was defeated, Thursday, Dec. 11, 2025, at the Statehouse in Indianapolis. (AP Photo/Michael Conroy)

FILE - This photo taken from video shows organizers rallying outside of the Ohio Statehouse to protest gerrymandering and advocate for lawmakers to draw fair maps in Columbus, Ohio, Sept. 17, 2025. (AP Photo/Patrick Aftoora-Orsagos, File)

Opponents of Missouri's Republican-backed congressional redistricting plan display a banner in protest at the State Capitol in Jefferson City, Missouri, Sept. 10, 2025. (AP Photo/David A. Lieb)