A prominent Georgian journalist was convicted Wednesday of slapping a police chief during an anti-government protest and sentenced to two years in prison in a case that was condemned by rights groups as curbing press freedom.

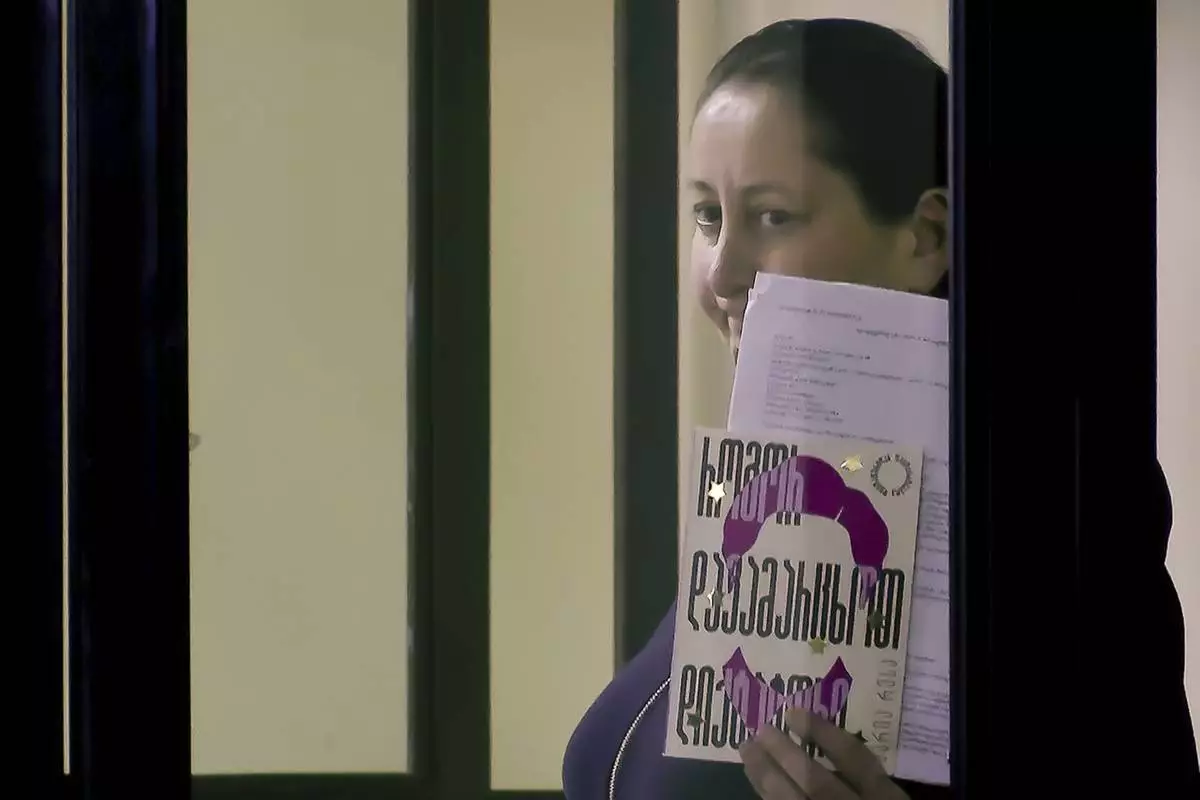

Mzia Amaghlobeli, who founded two of Georgia’s independent media outlets, was convicted in the coastal city of Batumi. She was initially charged with assault, an offense that carried a maximum prison sentence of up to seven years, but the judge in the end found her guilty on the lighter charge of resistance, threats or violence against a defender of the public order or other government official.

The case is just one of many to draw protests and international criticism in recent months as the ruling Georgian Dream party has been accused of eroding civil society and democratic rights in the South Caucasus nation.

A visibly gaunt Amaghlobeli, 50, heard the verdict in the Batumi City Court packed with journalists and supporters, while a protest was held outside the courthouse. Sporadic chants of “Free Mzia!” broke out both outside the courthouse and in the courtroom.

She was arrested Jan. 12, one of over 50 people taken into custody on criminal charges from a series of demonstrations in the country of 3.7 million.

Video shared by Georgian media outlets showed Amaghlobeli striking Police Chief Irakli Dgebuadze. Amaghlobeli said that after she was detained, Dgebuadze spat at her and tried to attack her.

Her lawyer told the court she reacted emotionally after getting caught in a stampede, falling, and witnessing the arrest of those close to her. She also said a police investigation was not impartial and she did not receive a fair trial.

In a closing statement Monday, Amaghlobeli described chaotic scenes at the protest.

“In a completely peaceful setting, the police suddenly appear, create chaos, and surround me with masked officers," she said. "As a result of strong pushes and blows from behind, I fall to the asphalt. Then they trample over me with their feet.”

She added that she was abused at the police station after her arrest.

She also thanked her colleagues and the activists for their continued resistance, and urged them to fight on.

“You must never lose faith in your own capabilities. There is still time. The fight continues— until victory!” she said.

Amaghlobeli is the founder and manager of investigative news outlet Batumelebi, which covers politics, corruption and human rights in Georgia. She also founded its sister publication, Netgazeti.

In a joint statement in January, 14 embassies, including those of France, Germany, the Netherlands and the U.K., said Amaghlobeli’s case represented “another worrying example of the intimidation of journalists in Georgia, restricting media freedom and freedom of expression.”

Gypsy Guillén Kaiser, advocacy and communications director for the Committee to Protect Journalists, warned that Amaghlobeli’s case was “a sign of the declining environment for press freedom in Georgia and a symbol for the fight between truth and control.”

“You have to decide whether you’re going to vilify journalists, criminalize them, and present them as nefarious characters with malicious intent in order to control information, or whether you’re going to have a public that is truly free, freely informed and empowered,” Guillén Kaiser said. “And that is a fundamental question for every country and for Georgia specifically right now.”

Leading Georgian officials defended her arrest. Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze accused her of seeking to fulfill a “directive” to discredit police but did not provide proof or say who was behind it.

“She attempted to discredit the law enforcement structures, to discredit the police, but she received exactly the kind of response such actions deserve,” he said. “Those who are trying to undermine statehood in Georgia are the ones who are upset by this. But this will not succeed — we will defend the interests of our state to the end.”

Georgia has seen widespread political unrest and protests since its parliamentary election on Oct. 26, which was won by Georgian Dream. Protesters and the country’s opposition declared the result illegitimate amid allegations of vote-rigging aided by Russia.

At the time, opposition leaders vowed to boycott sessions of parliament until a new election could be held under international supervision and alleged ballot irregularities were investigated.

Nearly all the leaders of Georgia’s pro-Western opposition parties have been jailed for refusing to testify at a parliamentary inquiry into alleged wrongdoing by the government of former President Mikhail Saakashvili, a probe that critics of Georgian Dream say is an act of political revenge.

The critics accuse Georgian Dream — established by Bidzina Ivanishvili, a billionaire who made his fortune in Russia — of becoming increasingly authoritarian and tilted toward Moscow, accusations the party has denied. It recently pushed through laws similar to those used by the Kremlin to crack down on freedom of speech and LGBTQ+ rights.

Among controversial legislation passed by Georgian Dream is the so-called “ foreign influence law," which requires organizations that receive more than 20% of their funding from abroad to register as “pursuing the interest of a foreign power.”

That law later was replaced with one called the Foreign Agent’s Registration Act, under which individuals or organizations considered as “agents of a foreign principal” must register with the government or face penalties, including criminal prosecution and imprisonment. Members of civil society fear that the law’s broad definition of “foreign agent” could be used to label any critical media outlet or nongovernmental organization as acting on behalf of a foreign entity.

Many independent news outlets receive grants from abroad to fund their work.

“I think that the main goal of the government was to scare us, for us to leave the country or shut down or change profession,” says Mariam Nikuradze, founder of the OC Media outlet. Most journalists still want to stay in the country, she said, and cover what she described as growing authoritarian rule.

“Everybody’s being very brave and everybody’s very motivated,” she said.

FILE - Protesters hold banners calling for the release of jailed journalist Mzia Amaghlobeli as they march through the streets in Tbilisi, Georgia, on Wednesday, Jan. 29, 2025. (AP Photo/Zurab Tsertsvadze, File)

FILE - In this image made from a Formula TV video, Mzia Amaghlobeli, a Georgian journalist and founder of the independent media outlets Batumelebi and Netgazeti, stands in a defendants' cage in a court in Batumi, Georgia, on Saturday, Feb. 1, 2025, and holds a book by Nobel Peace Prize laureate and journalist Maria Ressa titled, "How to Stand Up to a Dictator." (Formula TV via AP, File)