GAINESVILLE, Fla. (AP) — No matter the offense, states must educate students in juvenile detention. It’s a complicated challenge, no doubt — and success stories are scarce.

In Florida, where more than 1,000 students are in long-term confinement, the state last year put those kids' schooling online. That's despite strong evidence that online learning failed many kids during the pandemic. The state juvenile justice system contracted with the Florida Virtual School, one of the nation's oldest and largest online learning systems.

State leaders were hoping Florida Virtual School would bring more rigorous, uniform standards across their juvenile justice classrooms. When students left detention, the theory went, they could have the option of continuing in the online school until graduation.

But an AP investigation showed the online learning has been disastrous. Not only are students struggling to learn, but their frustration with virtual school also leads them to get into more trouble — thus extending their stay in juvenile detention.

Here are key takeaways from the investigation.

In interviews, students describe difficulty understanding their online schoolwork. In embracing Florida Virtual School, the residential commitment centers stopped providing in-person teachers for each subject, relying instead on the online faculty. The adults left in classrooms with detainees are largely serving as supervisors, and students say they rarely can answer their questions or offer assistance. Students also report difficulty getting help from the online teachers.

A dozen letters from incarcerated students, written to lawmakers and obtained by The Associated Press, describe online schoolwork that’s hard to access or understand — with little support from staff.

“Dear Law maker, I really be trying to do my work so I won’t be getting in trouble but I don’t be understanding the work,” wrote one student. “They don’t really hands on help me.”

Wrote another: “My zoom teachers they never email me back or try to help me with my work. It’s like they think we’re normal kids. Half of us don’t even know what we’re looking at.”

When students misbehave in long-term confinement, their stays can be extended. At the low end is a “level freeze,” when a student can't make progress toward release for a few days. For more serious offenses, students are sent back to county detention centers to face new charges. The weeks they spend there are called “dead time,” because they can't count toward their overall sentence.

And since Florida adopted online school in its residential commitment centers, students' frustration with their learning has led to longer stays.

One teen described having trouble passing an online pre-algebra test. The adult supervising the classroom couldn't help him. Frustrated, he threw his desk against the wall. He received a “level freeze” of three to five days, essentially extending his time at the residential commitment center.

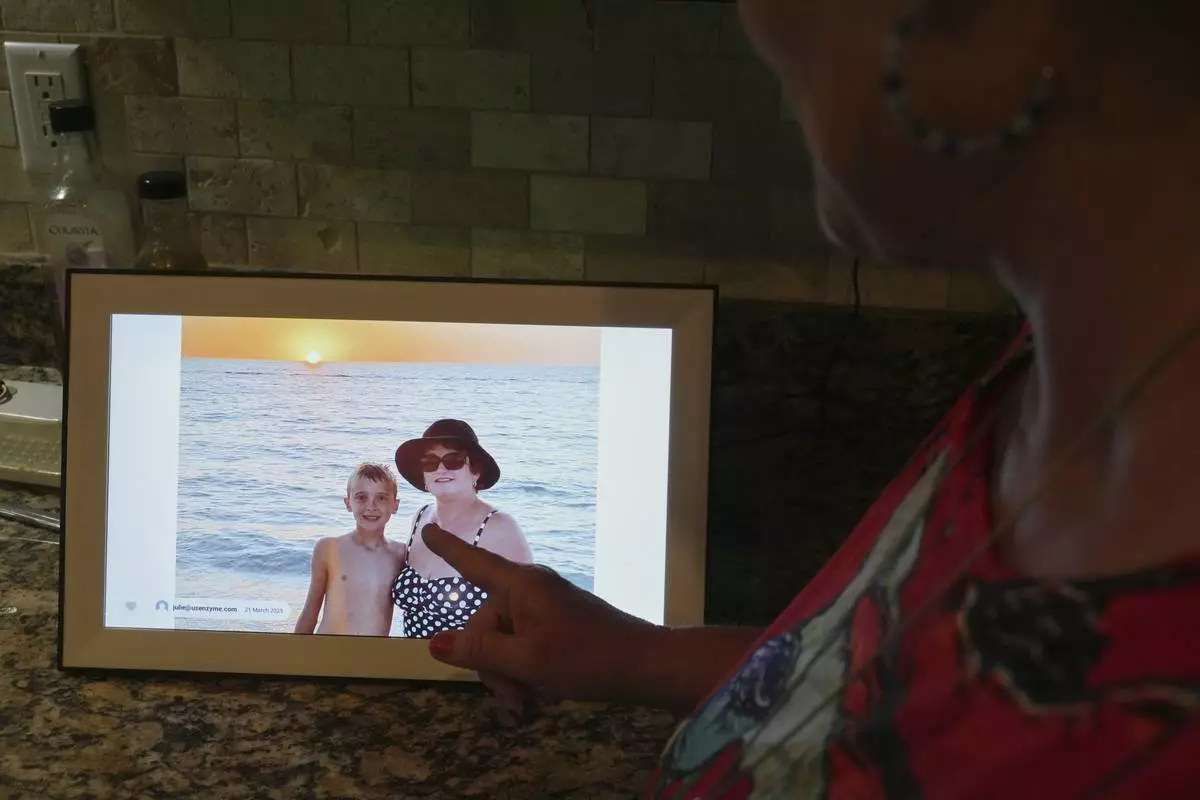

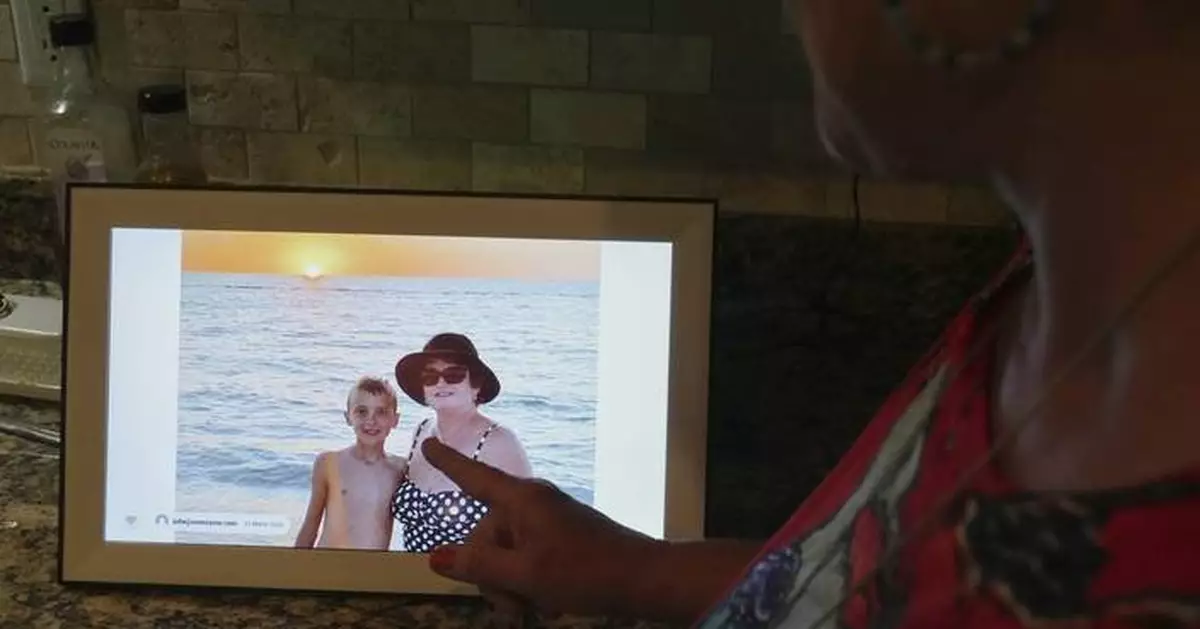

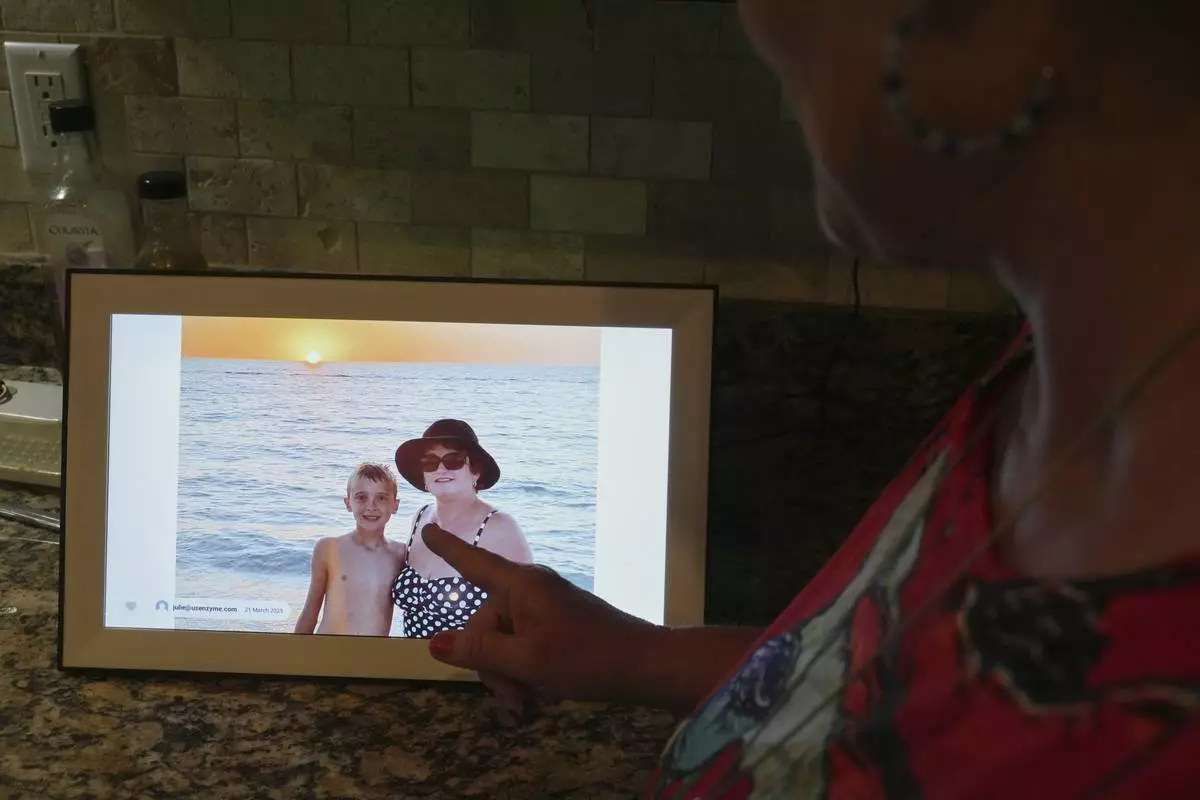

Another teen has broken three laptops, his grandmother says — two of them in frustration with not receiving help with online school. Each offense has added to his time in confinement. He initially was sentenced to six to nine months for breaking into a vape store, but now is on track to be locked up at least 28 months.

The total number of youth in Florida’s residential commitment centers increased to 1,388 in June, the latest data reported by the state, up 177 since July 2024, when the department adopted virtual instruction. That could indicate detainees are staying in confinement longer.

“Correlation does not equal causation,” responded Amanda Slama, a Department of Juvenile Justice spokeswoman.

One of the arguments Florida made for using online schooling was that students could continue their studies at Florida Virtual School after leaving detention, when many struggle to re-enter their local public schools.

That's not as easy as it seems. One student in AP's investigation was refused entry to his local middle school; officials said he was too old to enroll. When his parents tried to sign up for Florida Virtual, they were told they couldn't sign up so late in the school year.

Florida Virtual leaders say they provide a transition specialist for each student who leaves residential commitment to help them find a school. But this family says they were never offered this help. No one told them about a special version of Florida Virtual that would have allowed the student to pick up where he left off in detention.

The Associated Press receives support from the Public Welfare Foundation for reporting focused on criminal justice, and AP’s education coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Julie Nicoll shows shows an undated photo with her grandson Xavier Thursday, April 24, 2025, in Naples, Fla. Julie and her husband have spent more than $20,000 in legal fees trying to get him released from a youth detention center. (AP Photo/Marta Lavandier)

WASHINGTON (AP) — There is broad bipartisan support in the House and Senate for reviving federal health care subsidies that expired at the beginning of the year. But long-standing disagreements over abortion coverage are threatening to block any compromise and leave millions of Americans with higher premiums.

Despite significant progress, bipartisan Senate negotiations on the subsidies seemed to be near collapse at the end of the week as the abortion dispute appears intractable.

“Once we get past this issue, there’s decent agreement on everything else,” Sen. Bernie Moreno, R-Ohio, who has led the talks, told reporters.

But movement was hard to find.

Republicans were seeking stronger curbs on abortion coverage for those who purchase insurance off the marketplaces created by the Affordable Care Act. Democrats strongly opposed any such changes, especially in the wake of the Supreme Court overturning Roe vs. Wade in 2022. And advocacy groups on both sides were pushing against any compromise that they believe would weaken their positions.

The impasse was a familiar obstacle for lawmakers who have been arguing over the health law, known widely as “Obamacare,” since it was passed 16 years ago.

“The two sides are passionate about (abortion) so I think if they can find a way to bring it up, they probably will,” said Ivette Gomez, a senior policy analyst on women’s health policy for KFF, the health care research nonprofit.

The abortion dispute dates back to the weeks and months before President Barack Obama signed the health overhaul into law in 2010, when Democrats who controlled Congress added provisions ensuring that federal dollars subsidizing the health plans would not pay for elective abortions. The compromise came after negotiations with members of their own party whose opposition to abortion rights threatened to sink the legislation.

The final language allowed states to offer plans under the ACA that cover elective abortions, but said that federal money could not pay for them. States are now required to segregate funding for those procedures.

Since then, 25 states have passed laws prohibiting abortion coverage in ACA plans, 12 have passed laws requiring abortion coverage in the plans and 13 states and the District of Columbia have no coverage limitations or requirements, according to KFF. Some Republicans and anti-abortion groups now want to make it harder for the states that require or allow the coverage, arguing that the segregated funds are nothing more than a gimmick that allows taxpayer dollars to pay for abortions.

Senators involved in the negotiations said a potential compromise was to investigate some of those states to ensure that they are segregating the money correctly.

Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, who has led the negotiations with Moreno, said “the answer is to audit” those states and enforce the law if they are not properly segregating their funds.

But that plan was unlikely to win unanimity from Republicans, and Democrats have not signed on.

Negotiators were more optimistic last week, after President Donald Trump told House Republicans at a meeting that “you have to be a little flexible” on rules that federal dollars cannot be used for abortions.

Those words from the president, who has said little about whether he wants Congress to extend the subsidies, came just before a House vote on Democratic legislation that would extend the ACA tax credits for three years. After his comments, 17 Republicans voted with Democrats on the extension over the objections of GOP leadership and the House passed the bill with no new abortion restrictions.

Anti-abortion groups reacted swiftly.

Kelsey Pritchard, a spokeswoman for Susan B. Anthony Pro-Life America, said the group would not be supporting the 17 Republicans who voted for the extension. Trump’s comments were “a complete change in position for him” that brought “a lot of backlash and outcry” from the anti-abortion movement and voters opposed to abortion rights, she said.

Those who did not support changes to the ACA to reduce abortion coverage “are going to pay the price in the midterms” this year, Pritchard said. “We’re communicating to them that this isn’t acceptable.”

Democrats say the Republican effort to amend the law and increase restrictions on abortion is a distraction. They have been focused on extending the COVID-era subsidies that expired on Jan. 1 and had kept costs down for millions of people in the United States. The average subsidized enrollee is facing more than double the monthly premium costs for 2026, also according to KFF.

The two sides have been haggling since the fall, when Democrats voted to shut down the government for 43 days as they demanded negotiations on extending the subsidies. Republicans refused to negotiate until a small group of moderate Democrats agreed to vote with them and end the shutdown.

After the shutdown ended, Republicans made clear that they would not budge on the subsidies without changes on abortion, and the Senate voted on and rejected a three-year extension of the tax credits.

Maine Sen. Angus King, an independent who caucuses with Democrats, said at the time that making it harder to cover abortion was a “red line” for Democrats.

Republicans are going to “own these increases” in premiums, King said then.

The bipartisan group that has met in recent weeks has closed in on parts of an agreement, including a two-year deal that would extend the enhanced subsidy while adding new limits and also creating the option, in the second year, of a health savings account that Trump and Republicans prefer. The ACA open enrollment period would be extended to March 1 of this year, to allow people more time to figure out their coverage plans after the interruption of the enhanced subsidy.

But the abortion issue continues to stand in the way of a deal as Democrats seek to protect the carefully crafted compromise that helped pass the ACA 16 years ago.

“I have zero appetite to make it harder for people to access abortions,” said Sen. Chris Murphy, D-Conn.

Associated Press writers Ali Swenson in New York and Joey Cappelletti and Lisa Mascaro contributed to this report.

Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, chair of the Senate Appropriations Committee, is met by reporters outside the Senate chamber, at the Capitol in Washington, Tuesday, Jan. 6, 2026. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Sen. Bernie Moreno, R-Ohio, center, talks with reporters as he walks through the Ohio Clock Corridor at the Capitol, Tuesday, Jan. 13, 2026, in Washington. (AP Photo/Rod Lamkey, Jr.)

FILE - Pages from the U.S. Affordable Care Act health insurance website healthcare.gov are seen on a computer screen in New York, Aug. 19, 2025. (AP Photo/Patrick Sison, File)

FILE - The Capitol is seen at nightfall in Washington on Oct. 22, 2025. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite, File)