An American Orthodox archbishop's meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Alaska, in which they exchanged warm greetings and gifts of holy icons — is drawing a denunciation by Ukrainian Orthodox bishops in the U.S. They called it a “betrayal of Christian witness” in the wake of the Russia-Ukraine war.

Archbishop Alexei — the bishop of Alaska for the Orthodox Church in America, the now-independent offspring of the Russian Orthodox Church — met Friday with Putin at the Fort Richardson National Cemetery in Anchorage following Putin's summit with U.S. President Donald Trump. Putin also placed flowers at the graves of Soviet-era airmen killed during World War II.

“Russia has given us what’s most precious of all, which is the Orthodox faith, and we are forever grateful,” Alexei told Putin, alluding to Russian missionaries who brought the faith to Alaska when it was a czarist territory. He added that he visits Russia regularly and that when his priests and seminarians go there, they report back, “I’ve been home.”

Putin told him: “Please feel at home whenever you come.”

But critics said the meeting conferred legitimacy on Putin, on top of his being hosted by Trump on U.S. soil despite an arrest warrant issued in 2023 from the International Criminal Court, accusing Putin of war crimes in the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Leaders of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the USA blasted the meeting between the archbishop and Putin.

“Such gestures are not merely unfortunate — they are a betrayal of the Gospel of Christ and scandalous to the faithful,” the statement said, signed by the New Jersey-based church's top two leaders, Metropolitan Antony and Archbishop Daniel.

The Russian regime “is responsible for the invasion of the independent and peaceful nation of Ukraine and for the death of hundreds of thousands, for the disappearance of countless innocents, for the tearing of families apart, and for the deliberate destruction of Ukraine,” the statement said. “To extend warm words of welcome and admiration to this ‘leader’ is nothing less than an endorsement of his actions.”

The statement said that while the church preaches love and forgiveness, it “can never excuse or whitewash evil.”

The meeting between the archbishop and Putin is notable in how American churches are embroiled in controversies involving Orthodoxy in Ukraine, which arose even before the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and have worsened since. Orthodox Christianity is the majority religion in Russia and Ukraine.

There are multiple Eastern Orthodox jurisdictions in the United States, rooted in various immigrant communities of different nationalities. That includes Russia with the OCA and Ukraine with the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the USA. They generally share communion and cooperate in some areas but have separate hierarchies.

Putin gave Alexei icons of St. Herman — an early Russian missionary to Alaska — and of the Mother of God, which the archbishop received making the sign of the cross and kissing each icon. Alexei gave the Russian president an icon he had previously received as a gift upon becoming bishop.

The two did not discuss the war during the brief conversation, according to a video recording.

In a follow-up message emailed to Alaska priests, defending the visit, Alexei noted he had overseen three days of special services in Orthodox parishes across Alaska, in which worshippers offered prayers for peace in the name of Alaska saints and the Mother of God.

“When I expressed gratitude in that public moment, it was not praise for present politics, but a remembrance of the missionaries of earlier generations … who brought us the Orthodox faith at great cost,” Alexei said.

He also defended the icon exchange. “I must be clear: the veneration we give to holy icons is directed not to the one who gives them, but to the saint or feast they represent,” he said. “Even if the greatest sinner were beside me, the honor passes not to him but to heaven itself.”

He added: “I know that sacred gestures can be misunderstood, and I grieve if this has caused confusion or scandal.” He said it's important “to open whatever small door may be given for a pastoral word of peace.”

Moscow Patriarch Kirill has strongly supported the war, saying Russian soldiers who die in the line of duty in Ukraine have all of their sins forgiven and presiding over a council that declared the Russian invasion a “holy war.”

Putin himself regularly displays Orthodox piety — reflected in his making the sign of the cross at the Soviet graves and kissing the icons he gave to Alexei. Putin recently asserted without elaboration that one of the conditions for peace would have to be “providing an adequate environment for the Orthodox Church and the Christian faith in Ukraine.”

Ukraine's Orthodox population has been torn by schism. There are currently two main Orthodox groups with similar-sounding names there.

The Ukrainian Orthodox Church has historically been under the Moscow Patriarchate, which claims jurisdiction in Ukraine. Meanwhile, the breakaway Orthodox Church in Ukraine received recognition as an independent church by the Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople.

Both churches have denounced the Russian invasion, but the UOC has remained under suspicion even though it has tried to assert it is also independent of Moscow's control. (Neither should be confused with the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the USA, which operates on American soil.)

Ukraine’s parliament last year passed a law banning religious groups tied to the Russian Orthodox Church or any other faith group supporting Russia’s invasion. The measure was widely seen as targeting the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, and the Ukrainian government has insisted that church take various steps to show its independence, which its leader has refused to do, asserting the government's process is flawed and citing the church's proclamation of its independence in 2022.

The Ukrainian Council of Churches and Religious Organizations — a coalition that includes the Orthodox Church of Ukraine — issued a statement supporting the government's insistence that the UOC comply with its demands. It said Russia has broadly violated religious liberties in occupied Ukrainian territories. It contended that Ukraine honors religious freedom and pluralism while maintaining the right to make sure religion isn't being used to abet the invasion.

“It is widely known that the Russian Federation uses religion, particularly the Russian Orthodox Church, as a weapon to pursue its neo-imperial goals in various countries,” the statement said.

AP reporter Illia Novikov contributed to this report.

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

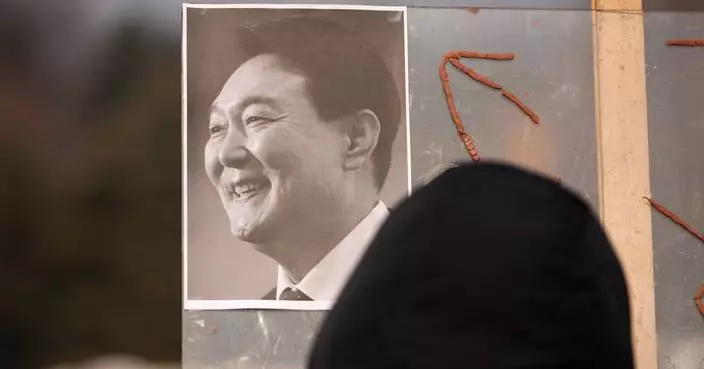

President Donald Trump and Russia's President Vladimir Putin arrive for a press conference at Joint Base Elmendorf- Richardson, Friday, Aug. 15, 2025, in Anchorage, Alaska. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

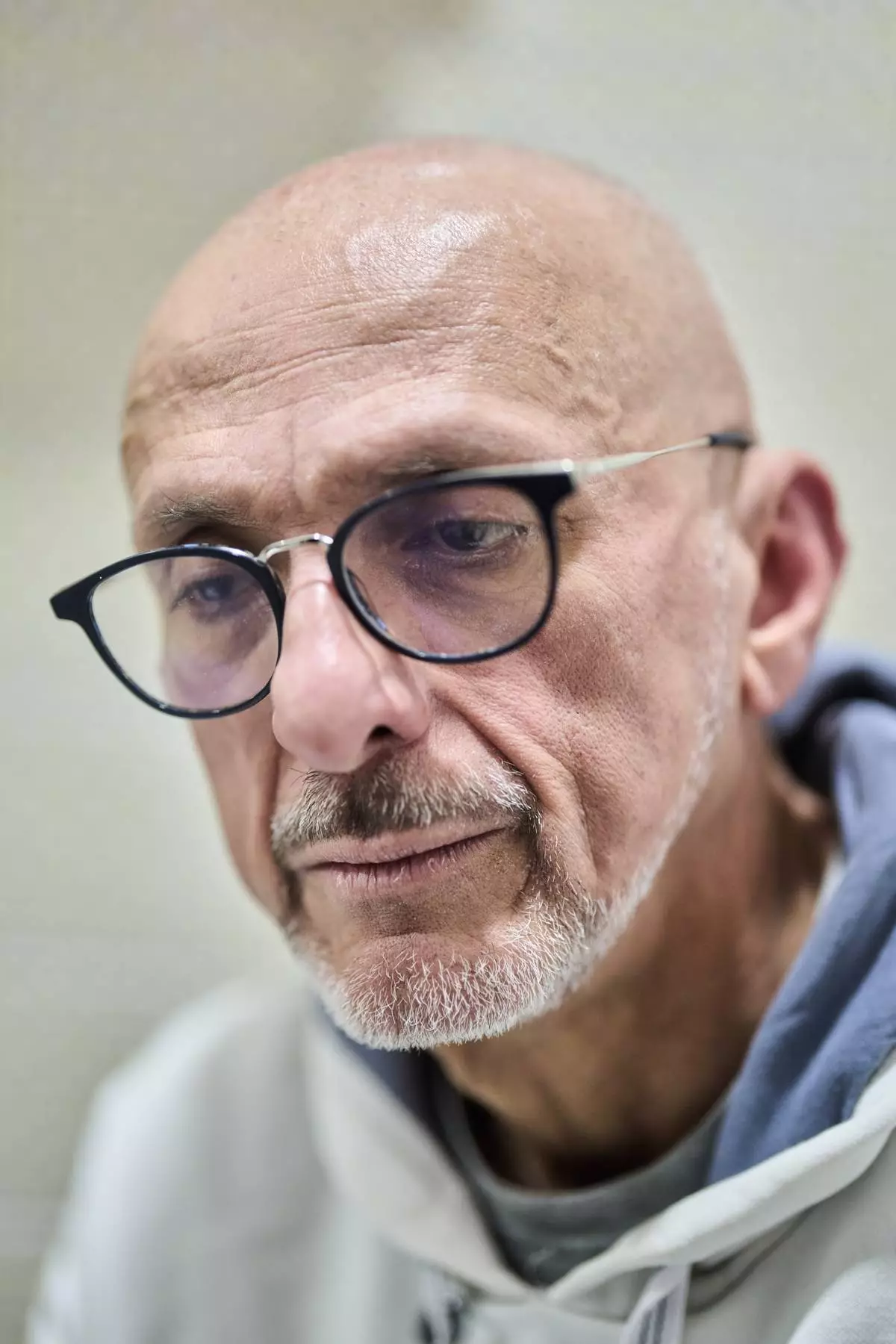

Russia's President Vladimir Putin, left, shakes hands with Alexei (John Trader), Archbishop of the Orthodox Church in America Diocese of Alaska after laying flowers to the graves of Soviet soldiers who died during World War II at Fort Richardson National Cemetery, Alaska, Friday, Aug. 15, 2025, after meeting with U.S. President Donald Trump. (Sergei Bobylev, Sputnik, Kremlin Pool Photo via AP)

Russia's President Vladimir Putin, right, and Alexei (John Trader), Archbishop of the Orthodox Church in America Diocese of Alaska talk after laying flowers to the graves of Soviet soldiers who died during World War II at Fort Richardson National Cemetery, Alaska, Friday, Aug. 15, 2025, after meeting with U.S. President Donald Trump. (Gavriil Grigorov, Sputnik, Kremlin Pool Photo via AP)