KAMPALA, Uganda (AP) — Uganda is one of at least four African nations that have agreed to receive immigrants deported from the United States.

The U.S. deported five men with criminal backgrounds to the southern African kingdom of Eswatini and sent eight others to South Sudan. Rwanda has said it will receive up to 250 migrants deported from the U.S.

Now, according to U.S. officials, Uganda is set to receive Kilmar Abrego Garcia, a construction worker who became the face of U.S. President Donald Trump’s hardline immigration policies when he was wrongfully deported in March to a notorious prison in his native El Salvador. He was returned to the U.S. in June, only to face human smuggling charges. He has pleaded not guilty.

Abrego Garcia was detained on Monday and homeland security officials said later he was being processed for transfer to Uganda, a country he has no cultural ties with. Some Ugandans have reacted with incredulity at the looming deportation of the high-profile detainee under an agreement whose terms are yet to be made public. Ugandan officials have only said they prefer to receive individuals originally from Africa and without a criminal background.

Here is a brief look at Uganda, an east African country of 45 million people.

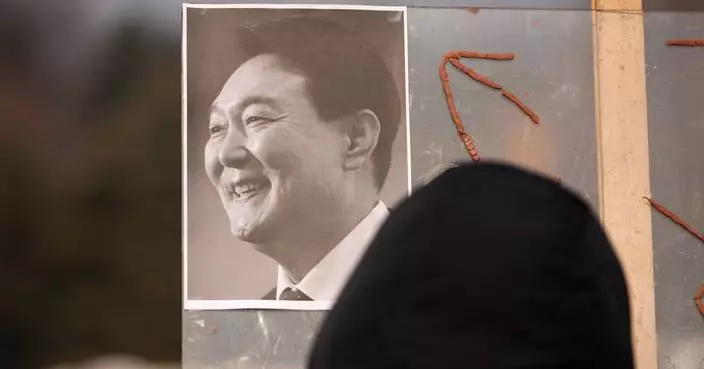

Ugandan negotiators involved in talks with the U.S. are believed to have been reporting directly to President Yoweri Museveni, an authoritarian who has been in power since 1986. The ruling party controls the national assembly, which is widely seen as weak and subservient to the presidency. In 2017 lawmakers removed a constitutional age limit on the presidency, leaving room for Museveni, who is 80, to rule for as long as he wishes.

Museveni is up for reelection in a presidential vote scheduled for January 2026. One of his long-time opponents, Kizza Besigye, has been jailed since November over treason charges his supporters say are politically motivated. His other opponent, the entertainer known as Bobi Wine, says he is harassed and unable to campaign across the country. Some critics say the agreement with the U.S. is a blessing for Museveni, who recently was under pressure from the international community over rights abuses and other issues.

Museveni says criticism of his long stay in power is unjustified because he is reelected every five years. Notably, he has a large following in rural areas, where Ugandans cite relative peace and security among reasons to keep him in power.

Uganda has the second-youngest population in the world, with more than three quarters of its people below the age of 35, according to the U.N. children’s agency. The results of a national census conducted last year show that 50.5% of Ugandans are children aged 17 and under and those between 18 and 30 account for 22.7% of the population. Many Ugandans migrate from rural areas to seek education and work opportunities in the capital, Kampala, a crowded city of 3 million where the primary form of public transport are passenger motorcycles known as boda-bodas. The development of public infrastructure, including hospitals, has not kept pace with a growing population.

After a 1907 visit to Uganda, Winston Churchill famously called the country “the pearl of Africa,” a tribute to its natural beauty and abundant wildlife.

Much of that abundance has been lost over the decades, but the country remains an attractive destination for safari visitors who come to see, especially, the endangered mountain gorillas. Uganda is home to about half the world’s remaining great apes, which can be tracked for a fee in a mountainous zone near the border with Rwanda and Congo.

Uganda's popular street snack, the “rolex,” is an omelet wrapped in chapati, a type of pan-fried flatbread. While a favorite among Ugandans, the snack has become the fascination for foreigners, some of whom have written about eating their rolex.

Rolex makers can be found in every town across Uganda, usually men who otherwise would be jobless if they didn’t take up such an opportunity. Their stands, illuminated by the red heat of charcoal rising from stoves, light up streets and dark alleys in Kampala at night.

In 2023, Ugandan lawmakers passed a bill imposing lengthy jail terms for same-sex relations, a move that reflected popular sentiment but drew international criticism from the U.S. and the World Bank. “Congratulations,” Parliament Speaker Anita Among told lawmakers after passing the bill. “Whatever we are doing, we are doing it for the people of Uganda.” Months later, Among was among high-profile Ugandans targeted for sanctions by the Biden administration.

Same-sex activity has long been punishable with life imprisonment under a colonial-era law, but Among and other Ugandan officials argued that a harsh new law was necessary to deter what they described as promoters of homosexuality. They had the president’s backing.

AP’s Africa coverage at: https://apnews.com/hub/africa

FILE -People wade into the waters of Lake Victoria, the world's second-largest freshwater lake, Nov. 25, 2024, in Entebbe, Uganda. (AP Photo/David Goldman, File)

People attend a protest rally at the Immigration and Customs Enforcement field office in Baltimore, Monday, Aug. 25, 2025, to support Kilmar Abrego Garciab. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

MADRID (AP) — Venezuelans living in Spain are watching the events unfold back home with a mix of awe, joy and fear.

Some 600,000 Venezuelans live in Spain, home to the largest population anywhere outside the Americas. Many fled political persecution and violence but also the country’s collapsing economy.

A majority live in the capital, Madrid, working in hospitals, restaurants, cafes, nursing homes and elsewhere. While some Venezuelan migrants have established deep roots and lives in the Iberian nation, others have just arrived.

Here is what three of them had to say about the future of Venezuela since U.S. forces deposed Nicolás Maduro.

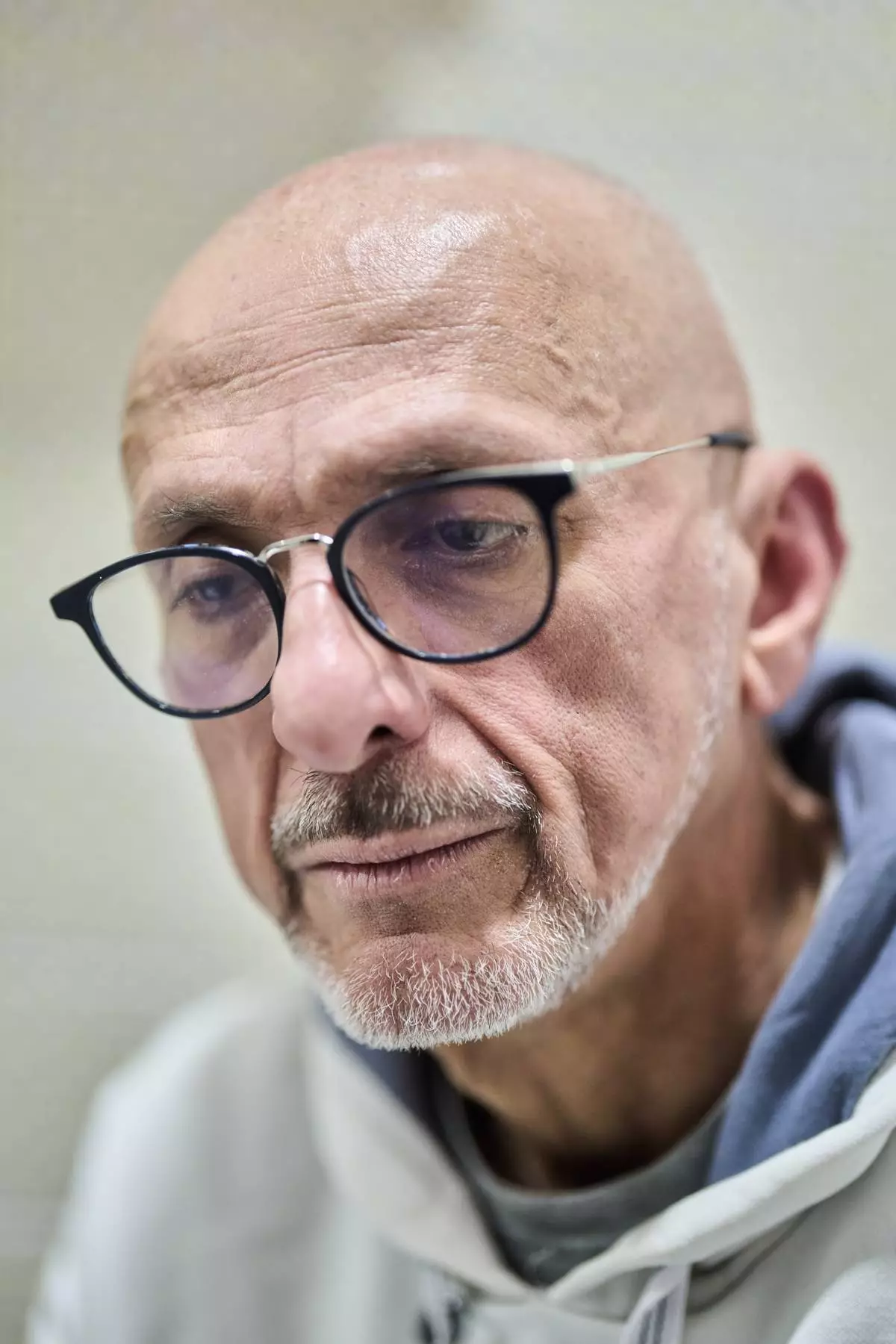

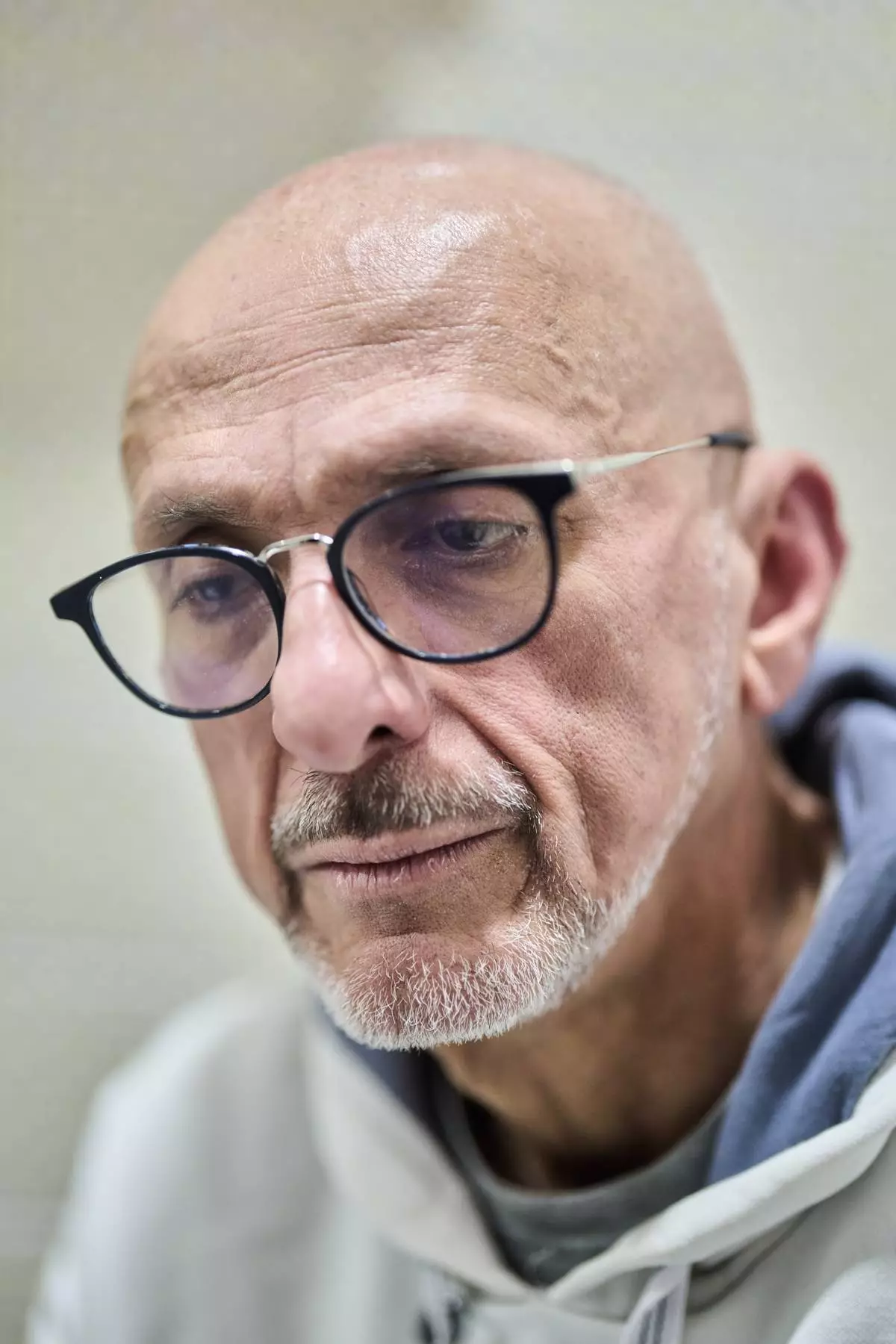

David Vallenilla woke up to text messages from a cousin on Jan. 3 informing him “that they invaded Venezuela.” The 65-year-old from Caracas lives alone in a tidy apartment in the south of Madrid with two Daschunds and a handful of birds. He was in disbelief.

“In that moment, I wanted certainty,” Vallenilla said, “certainty about what they were telling me.”

In June 2017, Vallenilla’s son, a 22-year-old nursing student in Caracas named David José, was shot point-blank by a Venezuelan soldier after taking part in a protest near a military air base in the capital. He later died from his injuries. Video footage of the incident was widely publicized, turning his son’s death into an emblematic case of the Maduro government’s repression against protesters that year.

After demanding answers for his son’s death, Vallenilla, too, started receiving threats and decided two years later to move to Spain with the help of a nongovernmental organization.

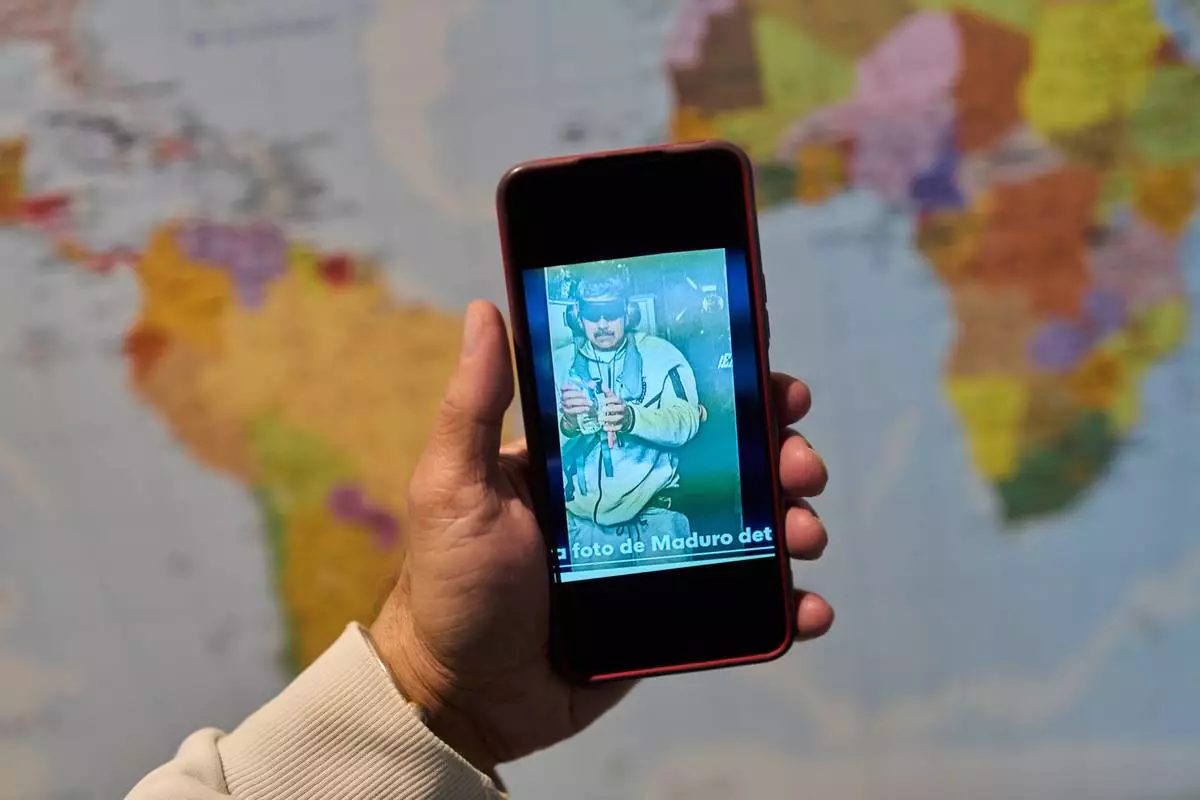

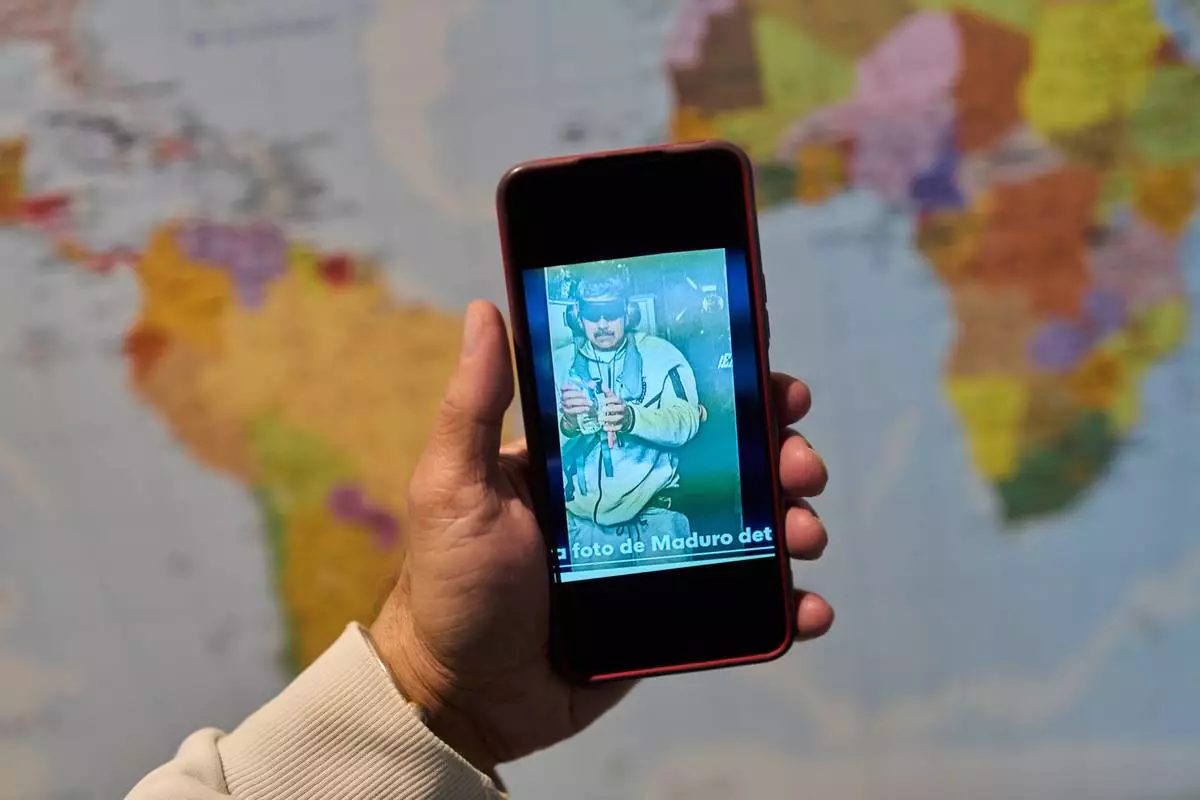

On the day of Maduro’s capture, Vallenilla said his phone was flooded with messages about his son.

“Many told me, ‘Now David will be resting in peace. David must be happy in heaven,’” he said. “But don't think it was easy: I spent the whole day crying.”

Vallenilla is watching the events in Venezuela unfold with skepticism but also hope. He fears more violence, but says he has hope the Trump administration can effect the change that Venezuelans like his son tried to obtain through elections, popular protests and international institutions.

“Nothing will bring back my son. But the fact that some justice has begun to be served for those responsible helps me see a light at the end of the tunnel. Besides, I also hope for a free Venezuela.”

Journalist Carleth Morales first came to Madrid a quarter-century ago when Hugo Chávez was reelected as Venezuela's president in 2000 under a new constitution.

The 54-year-old wanted to study and return home, taking a break of sorts in Madrid as she sensed a political and economic environment that was growing more and more challenging.

“I left with the intention of getting more qualified, of studying, and of returning because I understood that the country was going through a process of adaptation between what we had known before and, well, Chávez and his new policies," Morales said. "But I had no idea that we were going to reach the point we did.”

In 2015, Morales founded an organization of Venezuelan journalists in Spain, which today has hundreds of members.

The morning U.S. forces captured Maduro, Morales said she woke up to a barrage of missed calls from friends and family in Venezuela.

“Of course, we hope to recover a democratic country, a free country, a country where human rights are respected,” Morales said. “But it’s difficult to think that as a Venezuelan when we’ve lived through so many things and suffered so much.”

Morales sees it as unlikely that she would return home, having spent more than two decades in Spain, but she said she hopes her daughters can one day view Venezuela as a viable option.

“I once heard a colleague say, ‘I work for Venezuela so that my children will see it as a life opportunity.’ And I adopted that phrase as my own. So perhaps in a few years it won’t be me who enjoys a democratic Venezuela, but my daughters.”

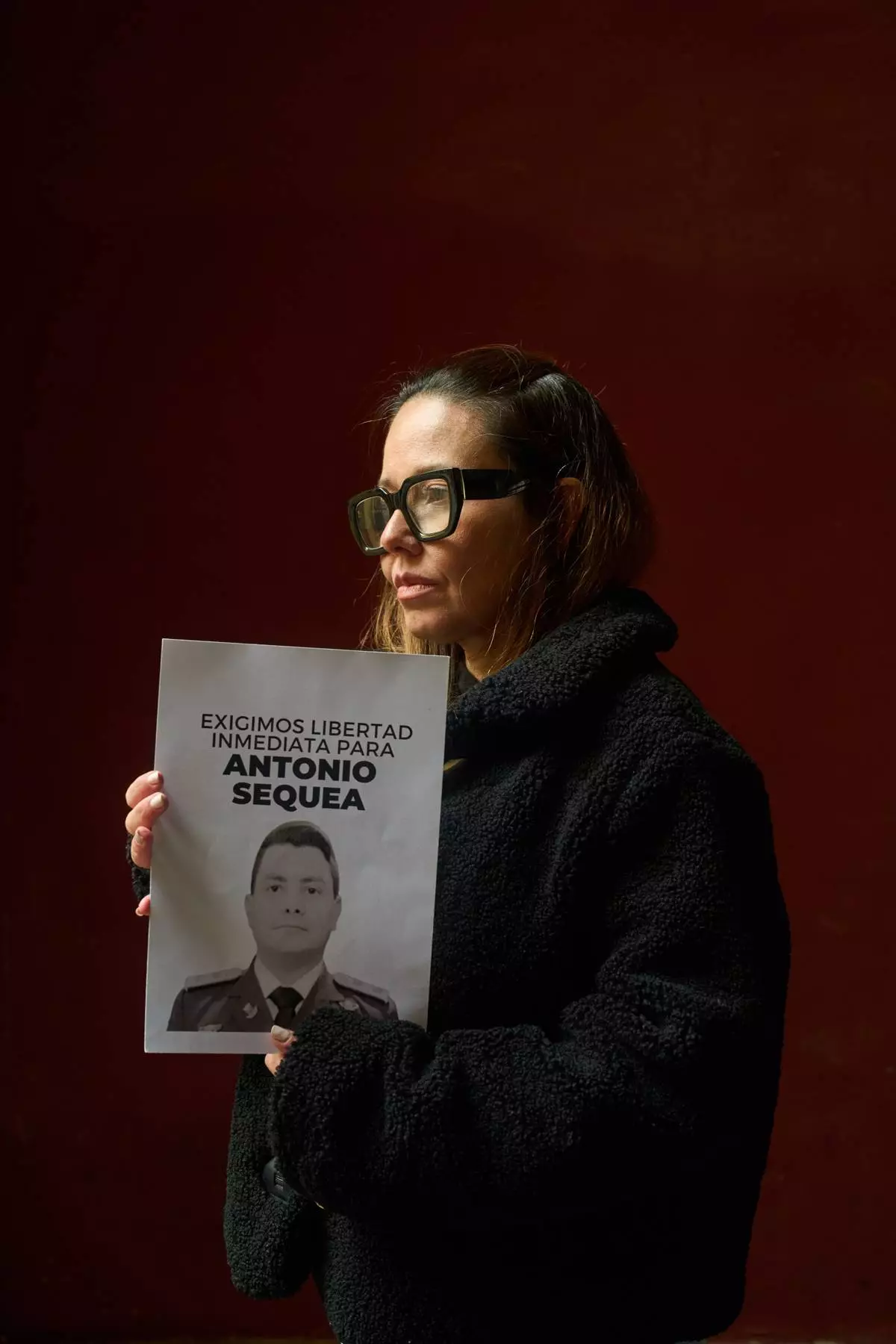

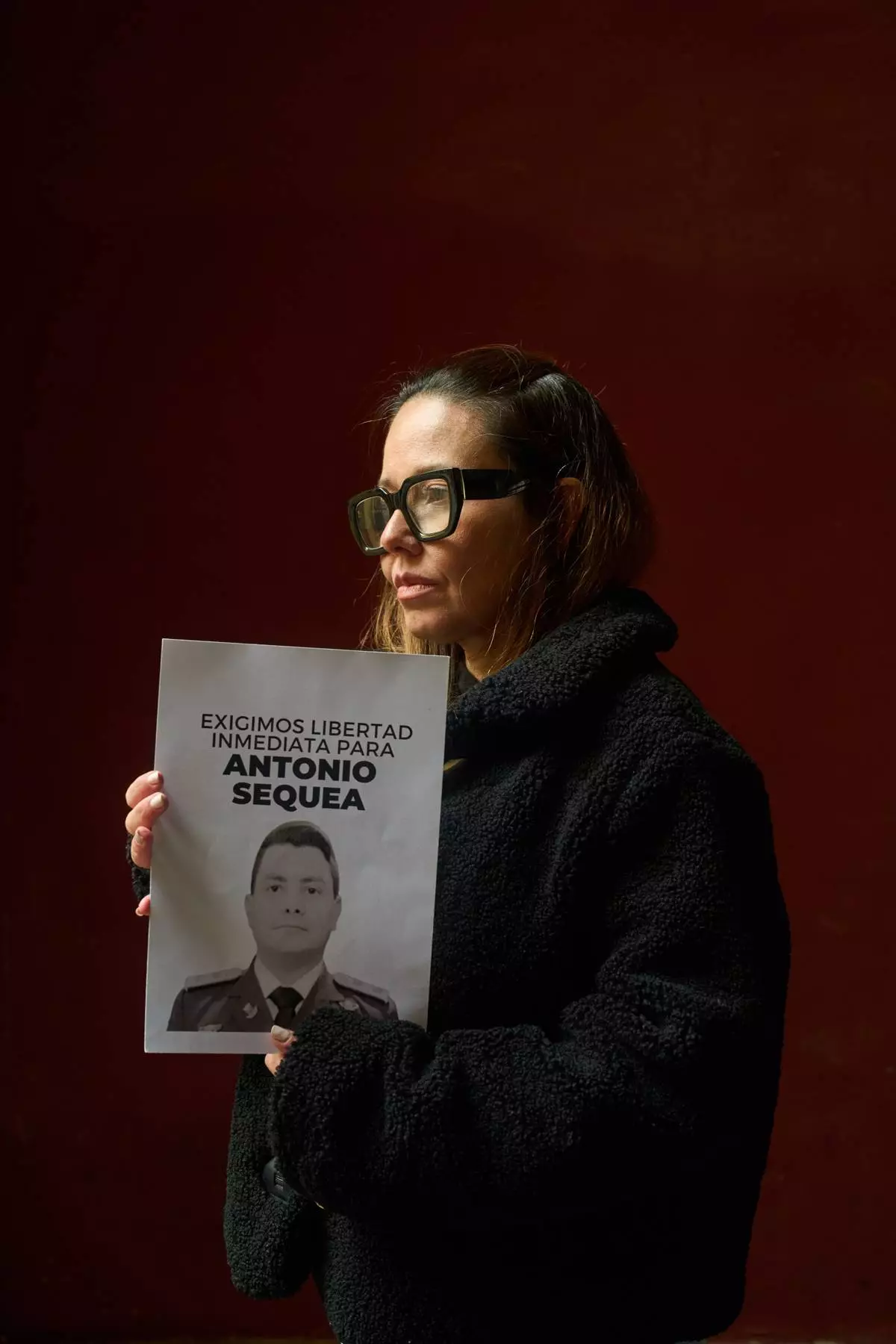

For two weeks, Verónica Noya has waited for her phone to ring with the news that her husband and brother have been freed.

Noya’s husband, Venezuelan army Capt. Antonio Sequea, was imprisoned in 2020 after having taken part in a military incursion to oust Maduro. She said he remains in solitary confinement in the El Rodeo prison in Caracas. For 20 months, Noya has been unable to communicate with him or her brother, who was also arrested for taking part in the same plot.

“That’s when my nightmare began,” Noya said.

Venezuelan authorities have said hundreds of political prisoners have been released since Maduro's capture, while rights groups have said the real number is a fraction of that. Noya has waited in agony to hear anything about her four relatives, including her husband's mother, who remain imprisoned.

Meanwhile, she has struggled with what to tell her children when they ask about their father's whereabouts. They left Venezuela scrambling and decided to come to Spain because family roots in the country meant that Noya already had a Spanish passport.

Still, she hopes to return to her country.

“I’m Venezuelan above all else,” Noya said. “And I dream of seeing a newly democratic country."

Venezuelan journalist Caleth Morales works in her apartment's kitchen in Madrid, Wednesday, Jan. 14, 2026. (AP Photo/Bernat Armangue)

David Vallenilla, father of the late David José Vallenilla Luis, sits in his apartment's kitchen in Madrid, Tuesday, Jan. 13, 2026. (AP Photo/Bernat Armangue)

Veronica Noya holds a picture of her husband Antonio Sequea in Madrid, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026. (AP Photo/Bernat Armangue)

David Vallenilla holds a picture of deposed President Nicolas Maduro, blindfolded and handcuffed, during an interview with The Associated Press at his home in Madrid, Tuesday, Jan. 13, 2026. (AP Photo/Bernat Armangue)

Pictures of the late David José Vallenilla Luis are placed in the living room of his father, David José Vallenilla, in Madrid, Tuesday, Jan. 13, 2026. (AP Photo/Bernat Armangue)