PANAMA CITY (AP) — For centuries, Panama served as a natural bridge for global trade. Mule trains hauled treasure over stone-paved trails, riverboats floated gold and silver down the Chagres River to Caribbean ports like Portobelo, guarded by the cannons of Fort San Lorenzo, and later, the world’s first transcontinental railroad ferried passengers and cargo from ocean to ocean.

This photo journey looks back at the routes that carried the world across Panama’s isthmus long before the first lock opened in the Panama Canal.

Click to Gallery

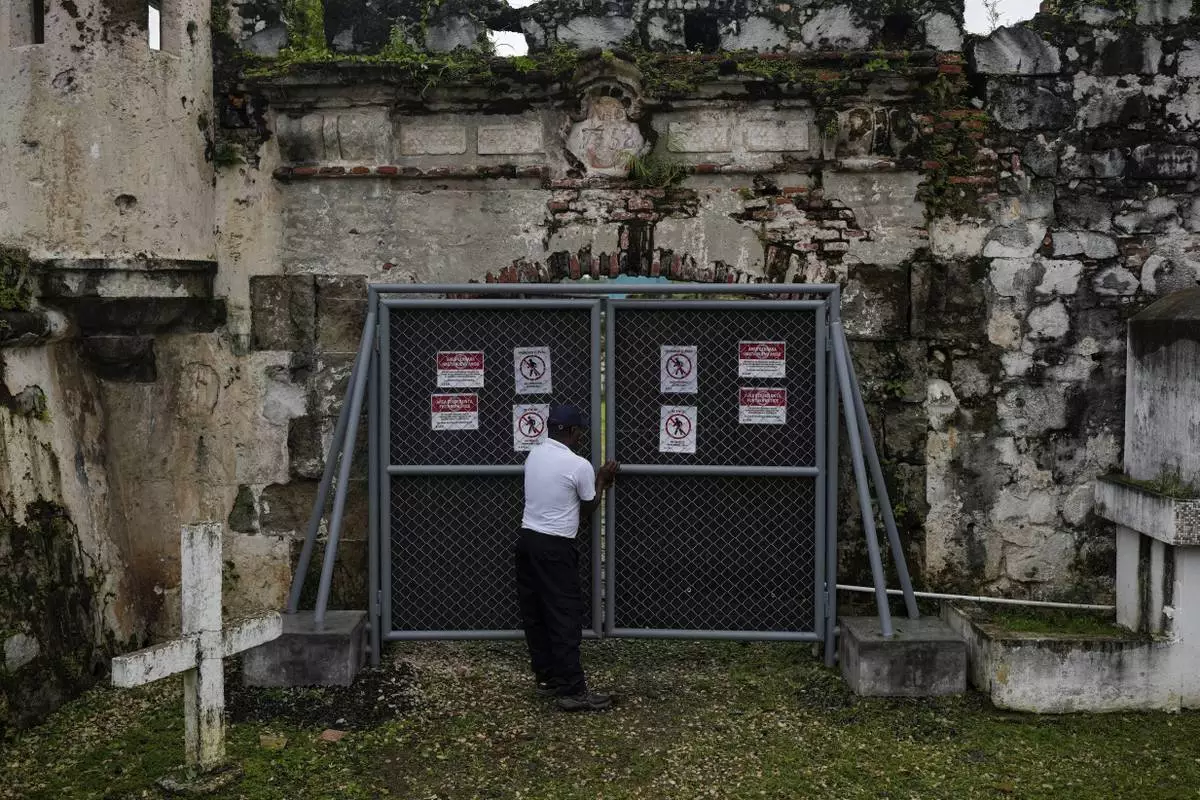

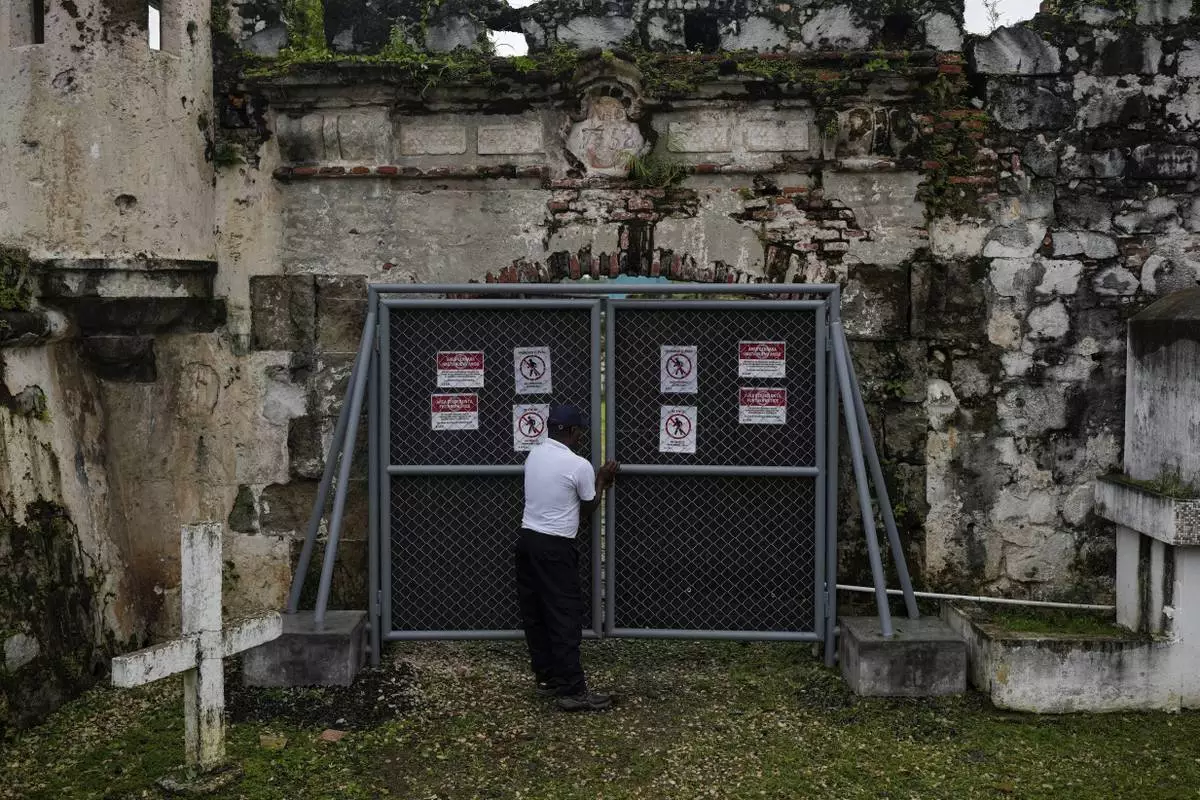

A security guard closes a gate of Fort San Jeronimo, a 17th-century Spanish fort that defended the Caribbean port of Portobelo, where treasure fleets loaded silver and gold for shipment to Europe, in Panama, Thursday, Aug. 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Embera Indigenous guides wait for the return of visitors touring the Chagres River, once the main colonial waterway carrying goods across Panama, between the Pacific Ocean and Caribbean, Saturday, Aug. 16, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Residents cross a colonial-era bridge in Portobelo, a town on Panama's Caribbean coast that was once a key port where Spanish treasure fleets loaded silver and gold for shipment to Europe, Thursday, Aug. 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

The old town "Casco Viejo" of Panama City, built after pirates destroyed the first settlement, overlooks the Bay of Panama on the Pacific Ocean, Sunday, Aug. 24, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

A park ranger walks along the "Camino de Cruces," a colonial stone road in Panama City built in the 16th century for mule trains carrying treasure across the isthmus from the Pacific to the Caribbean, Wednesday, Aug. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Tourists swim in a tributary of the Chagres River in Panama, once the main colonial waterway used to transport treasure in canoes and barges from the Pacific to the Caribbean for shipment to Spain, Saturday, Aug. 16, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Visitors tour Fort San Lorenzo, a 16th-century Spanish fortress guarding the mouth of the Chagres River, once the main colonial waterway linking the Pacific and Caribbean, in Colon, Panama, Tuesday, Aug. 12, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

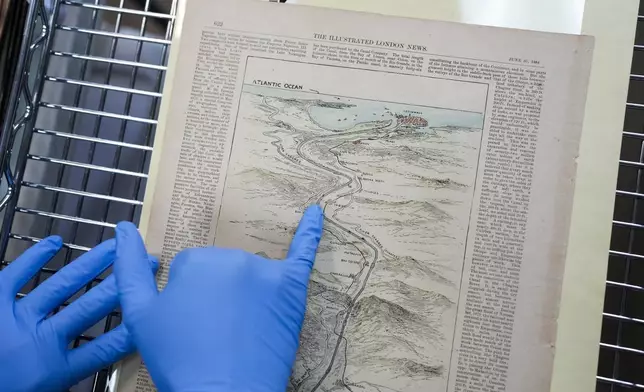

Researcher Esteban Zabala presents an 1888 map of the world's first transcontinental railway, a document that also included early canal route proposals, at the Panama Canal Museum in Panama City, Wednesday, Aug. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

A tourist stands at the Golden Altar inside Saint Joseph Church, a baroque piece covered in gold leaf built in the 17th century after Panama City was relocated from its first settlement destroyed by pirates, in "Casco Viejo," the historic district of Panama City, Friday, Aug. 15, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Fort San Lorenzo, built by the Spanish in the 16th century to guard the mouth of the Chagres River, stands above the bank of the main waterway of colonial trade across the isthmus, in Colon, Panama, Tuesday, Aug. 12, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

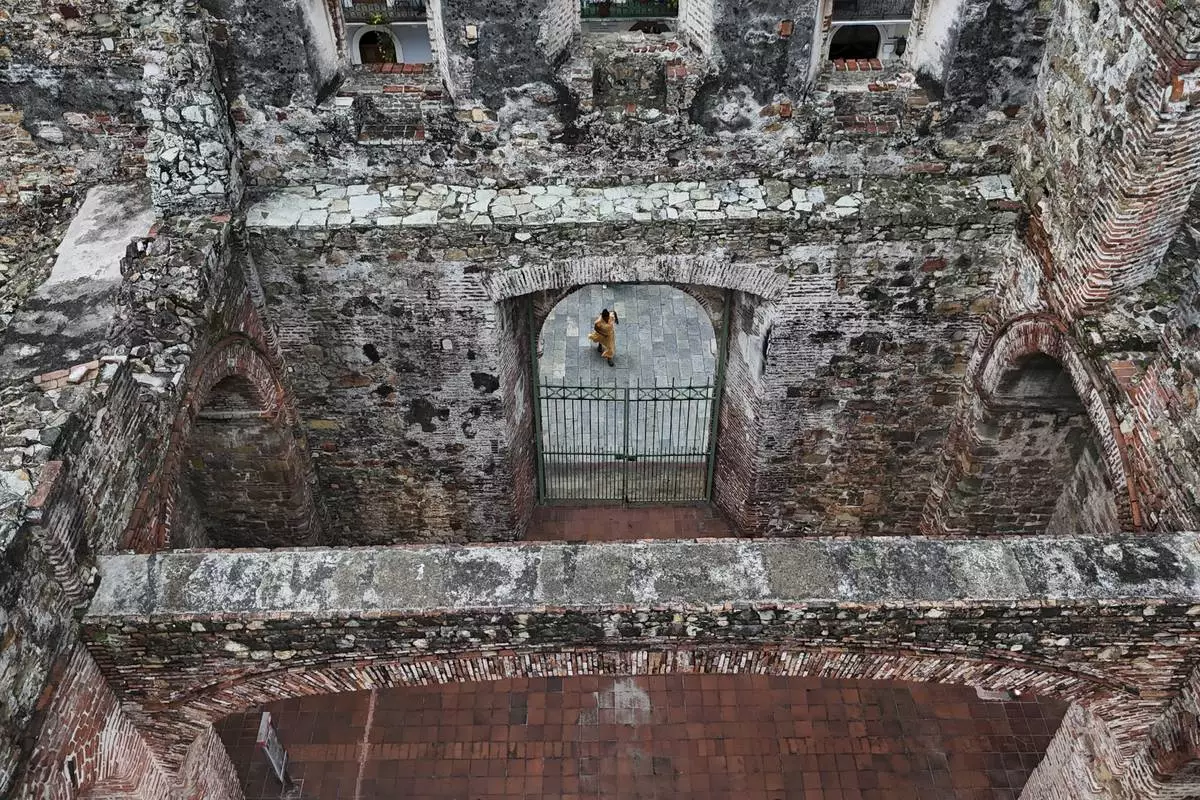

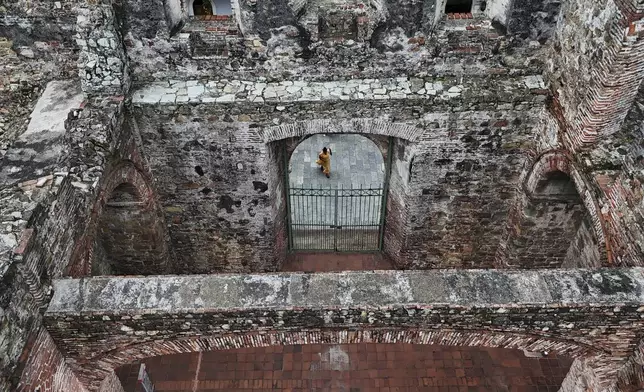

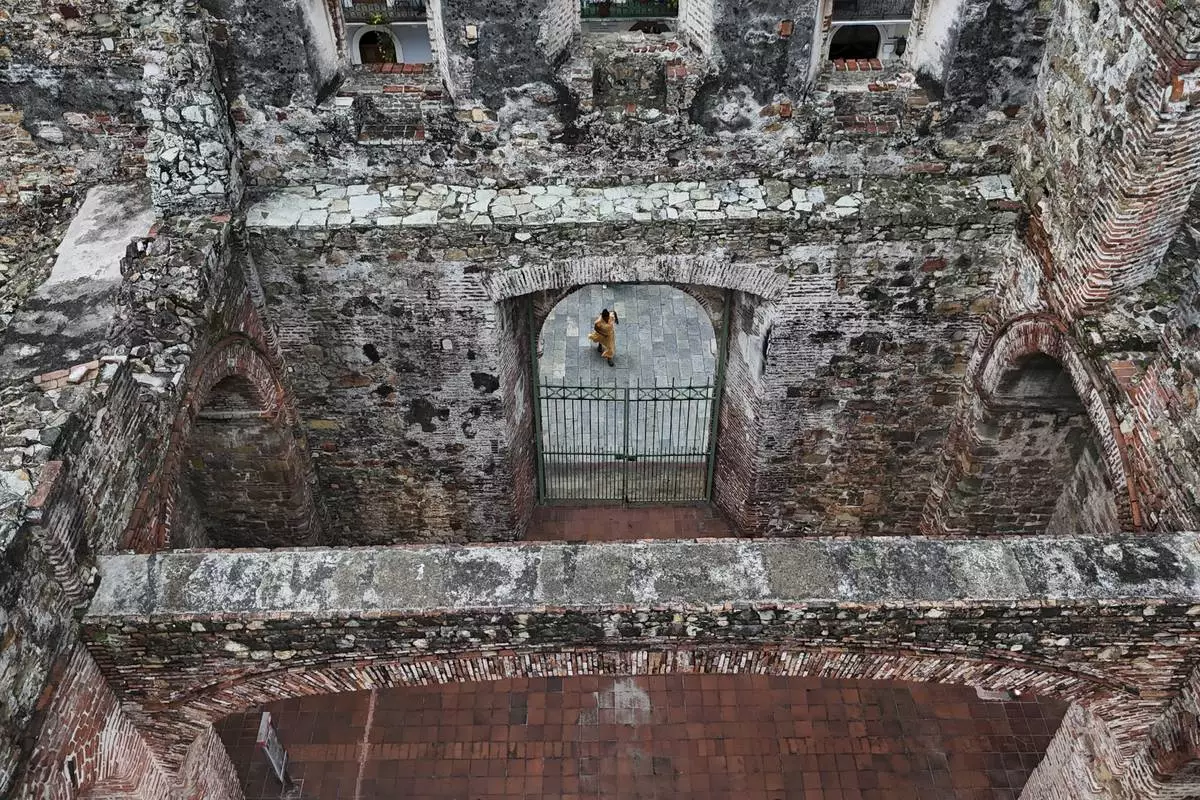

Visitors tour the ruins of Old Panama, the city's first colonial settlement founded in 1519 by Spanish conqueror Pedro Arias de Avila, in Panama City, Friday, Aug. 15, 2025.(AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

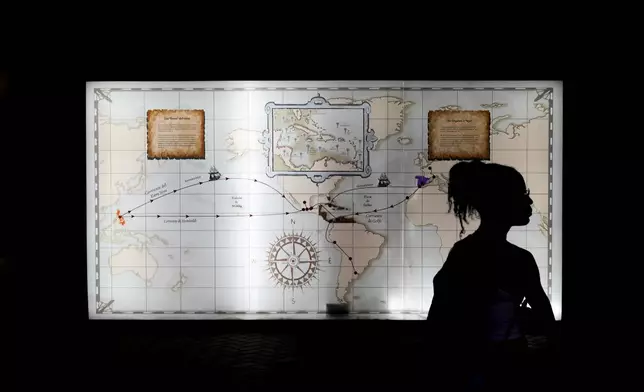

Tourists at the Old Panama Museum look at a topical map of Panama City's first colonial settlement, founded in 1519, in Panama City, Friday, Aug. 15, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

A tourist visits the ruins of Santo Domingo church, built in the 17th century after the city was relocated from its first colonial settlement, which had been destroyed by pirates, in "Casco Viejo," the historic district of Panama City, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Sunday, Aug. 10, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

A man paddles along the Chagres River, once the main colonial waterway crossing Panama and connecting the Pacific with Caribbean, Saturday, Aug. 16, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Youths climb a colonial-era wall to dive into the sea in the "Casco Viejo," the historic district of Panama City, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Sunday, Aug. 10, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

A tourist stands in front of a map outlining colonial interoceanic trade routes at the museum of Fort San Lorenzo, a 16th-century Spanish fortress that guarded the Caribbean entrance to the Chagres River, in Colon, Panama, Tuesday, Aug. 12, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

A park ranger walks along the "Camino de Cruces," a colonial road built by the Spanish to transport treasure across the isthmus to the Caribbean for shipment to Europe, in Panama City, Wednesday, Aug. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

A young woman poses for photos inside a former bastion that was part of the colonial defenses against pirates in Casco Viejo, the historic district of Panama City, also a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Sunday, Aug. 10, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Ruins of the old bell tower in "Panama Viejo," or Old Panama, the first permanent Spanish settlement on the Pacific coast of the Americas, is backdropped by the modern skyline of Panama City, Wednesday, July 30, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

These crossings made Panama one of the world’s most strategic corridors long before engineers carved the canal. Today, traces of those forgotten routes remain: moss-covered cobblestones hidden in the jungle, the colonial ruins of Panama Viejo, sacked by pirate Henry Morgan and later re-founded, fort walls crumbling above the sea, and the Chagres still winding on as a silent witness to centuries of passage.

This documentary photo story has been curated by AP photo editors.

A security guard closes a gate of Fort San Jeronimo, a 17th-century Spanish fort that defended the Caribbean port of Portobelo, where treasure fleets loaded silver and gold for shipment to Europe, in Panama, Thursday, Aug. 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Embera Indigenous guides wait for the return of visitors touring the Chagres River, once the main colonial waterway carrying goods across Panama, between the Pacific Ocean and Caribbean, Saturday, Aug. 16, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Residents cross a colonial-era bridge in Portobelo, a town on Panama's Caribbean coast that was once a key port where Spanish treasure fleets loaded silver and gold for shipment to Europe, Thursday, Aug. 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

The old town "Casco Viejo" of Panama City, built after pirates destroyed the first settlement, overlooks the Bay of Panama on the Pacific Ocean, Sunday, Aug. 24, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

A park ranger walks along the "Camino de Cruces," a colonial stone road in Panama City built in the 16th century for mule trains carrying treasure across the isthmus from the Pacific to the Caribbean, Wednesday, Aug. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Tourists swim in a tributary of the Chagres River in Panama, once the main colonial waterway used to transport treasure in canoes and barges from the Pacific to the Caribbean for shipment to Spain, Saturday, Aug. 16, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Visitors tour Fort San Lorenzo, a 16th-century Spanish fortress guarding the mouth of the Chagres River, once the main colonial waterway linking the Pacific and Caribbean, in Colon, Panama, Tuesday, Aug. 12, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Researcher Esteban Zabala presents an 1888 map of the world's first transcontinental railway, a document that also included early canal route proposals, at the Panama Canal Museum in Panama City, Wednesday, Aug. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

A tourist stands at the Golden Altar inside Saint Joseph Church, a baroque piece covered in gold leaf built in the 17th century after Panama City was relocated from its first settlement destroyed by pirates, in "Casco Viejo," the historic district of Panama City, Friday, Aug. 15, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Fort San Lorenzo, built by the Spanish in the 16th century to guard the mouth of the Chagres River, stands above the bank of the main waterway of colonial trade across the isthmus, in Colon, Panama, Tuesday, Aug. 12, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Visitors tour the ruins of Old Panama, the city's first colonial settlement founded in 1519 by Spanish conqueror Pedro Arias de Avila, in Panama City, Friday, Aug. 15, 2025.(AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Tourists at the Old Panama Museum look at a topical map of Panama City's first colonial settlement, founded in 1519, in Panama City, Friday, Aug. 15, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

A tourist visits the ruins of Santo Domingo church, built in the 17th century after the city was relocated from its first colonial settlement, which had been destroyed by pirates, in "Casco Viejo," the historic district of Panama City, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Sunday, Aug. 10, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

A man paddles along the Chagres River, once the main colonial waterway crossing Panama and connecting the Pacific with Caribbean, Saturday, Aug. 16, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Youths climb a colonial-era wall to dive into the sea in the "Casco Viejo," the historic district of Panama City, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Sunday, Aug. 10, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

A tourist stands in front of a map outlining colonial interoceanic trade routes at the museum of Fort San Lorenzo, a 16th-century Spanish fortress that guarded the Caribbean entrance to the Chagres River, in Colon, Panama, Tuesday, Aug. 12, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

A park ranger walks along the "Camino de Cruces," a colonial road built by the Spanish to transport treasure across the isthmus to the Caribbean for shipment to Europe, in Panama City, Wednesday, Aug. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

A young woman poses for photos inside a former bastion that was part of the colonial defenses against pirates in Casco Viejo, the historic district of Panama City, also a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Sunday, Aug. 10, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Ruins of the old bell tower in "Panama Viejo," or Old Panama, the first permanent Spanish settlement on the Pacific coast of the Americas, is backdropped by the modern skyline of Panama City, Wednesday, July 30, 2025. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

HAVANA (AP) — Cuban soldiers wearing white gloves marched out of a plane on Thursday carrying urns with the remains of the 32 Cuban officers killed during a stunning U.S. attack on Venezuela as trumpets and drums played solemnly at Havana's airport.

Nearby, thousands of Cubans lined one of Havana’s most iconic streets to await the bodies of colonels, lieutenants, majors and captains as the island remained under threat by the administration of U.S. President Donald Trump.

The soldiers' shoes clacked as they marched stiff-legged into the headquarters of the Ministry of the Armed Forces, next to Revolution Square, with the urns and placed them on a long table next to the pictures of those killed so people could pay their respects.

Thursday’s mass funeral was only one of a handful that the Cuban government has organized in almost half a century.

Hours earlier, state television showed images of more than a dozen wounded people described as “combatants” accompanied by Cuban Foreign Minister Bruno Rodríguez arriving Wednesday night from Venezuela. Some were in wheelchairs.

Those injured and the remains of those killed arrived as tensions grow between Cuba and the U.S., with Trump recently demanding that the Caribbean country make a deal with him before it is “too late.” He did not explain what kind of deal.

Trump also has said that Cuba will no longer live off Venezuela's money and oil. Experts warn that the abrupt end of oil shipments could be catastrophic for Cuba, which is already struggling with serious blackouts and a crumbling power grid.

Officials unfurled a massive flag at Havana's airport as President Miguel Díaz-Canel, clad in military garb as commander of Cuba's Armed Forces, stood silent next to former President Raúl Castro, with what appeared to be the relatives of those killed looking on nearby.

Cuban Interior Minister Lázaro Alberto Álvarez Casa said Venezuela was not a distant land for those killed, but a “natural extension of their homeland.”

“The enemy speaks to an audience of high-precision operations, of troops, of elites, of supremacy,” Álvarez said in apparent reference to the U.S. “We, on the other hand, speak of faces, of families who have lost a father, a son, a husband, a brother.”

Álvarez called those slain “heroes,” saying that they were an example of honor and “a lesson for those who waver.”

“We reaffirm that if this painful chapter of history has demonstrated anything, it is that imperialism may possess more sophisticated weapons; it may have immense material wealth; it may buy the minds of the wavering; but there is one thing it will never be able to buy: the dignity of the Cuban people,” he said.

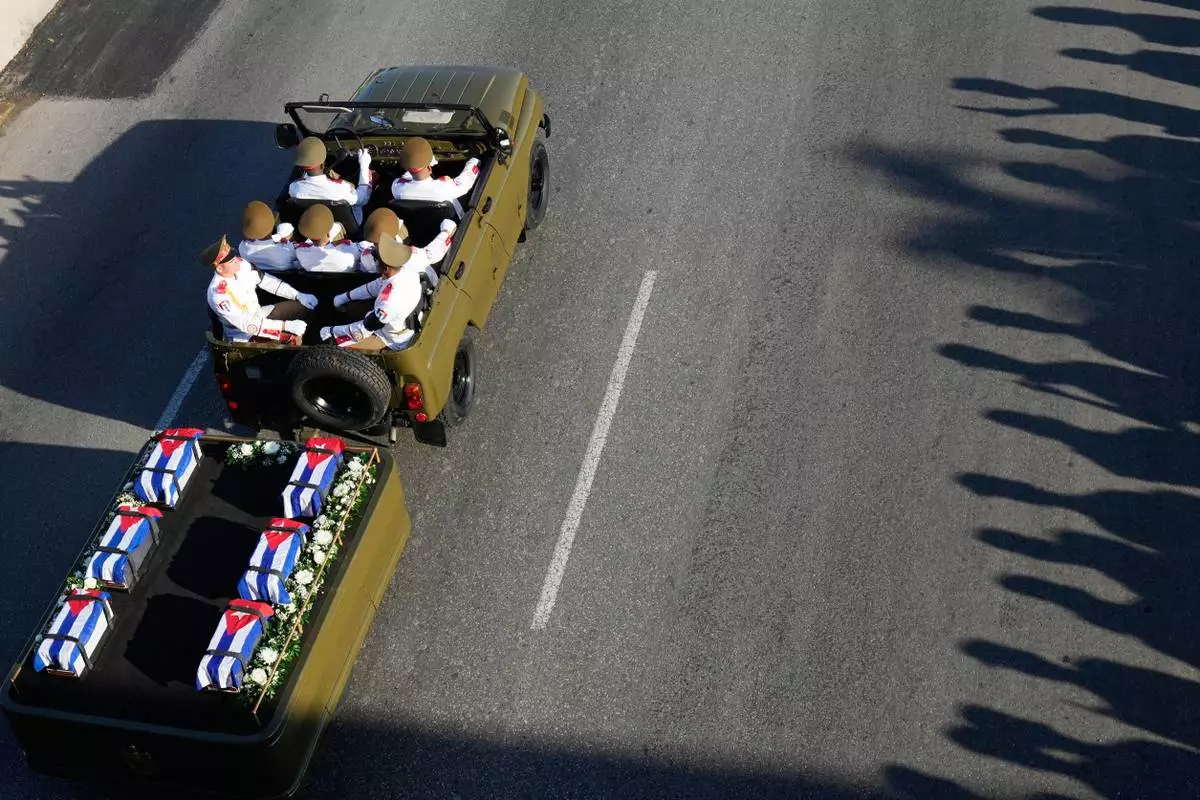

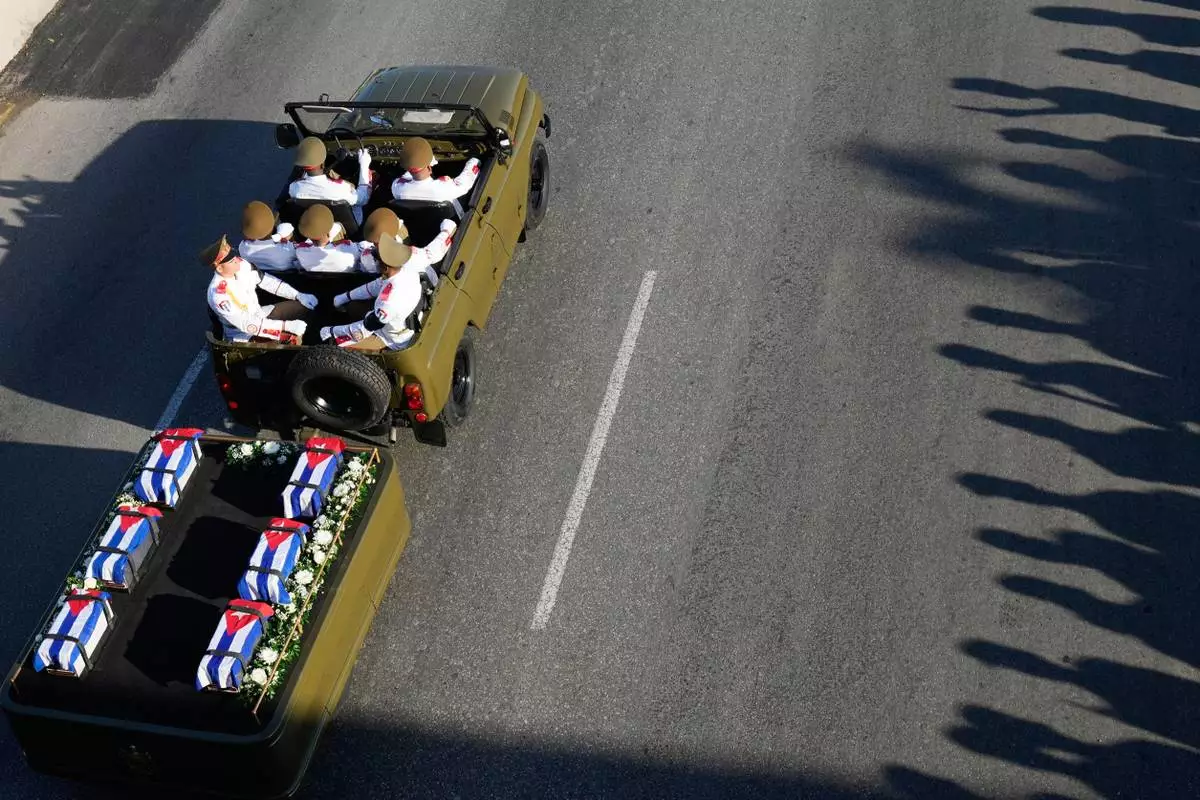

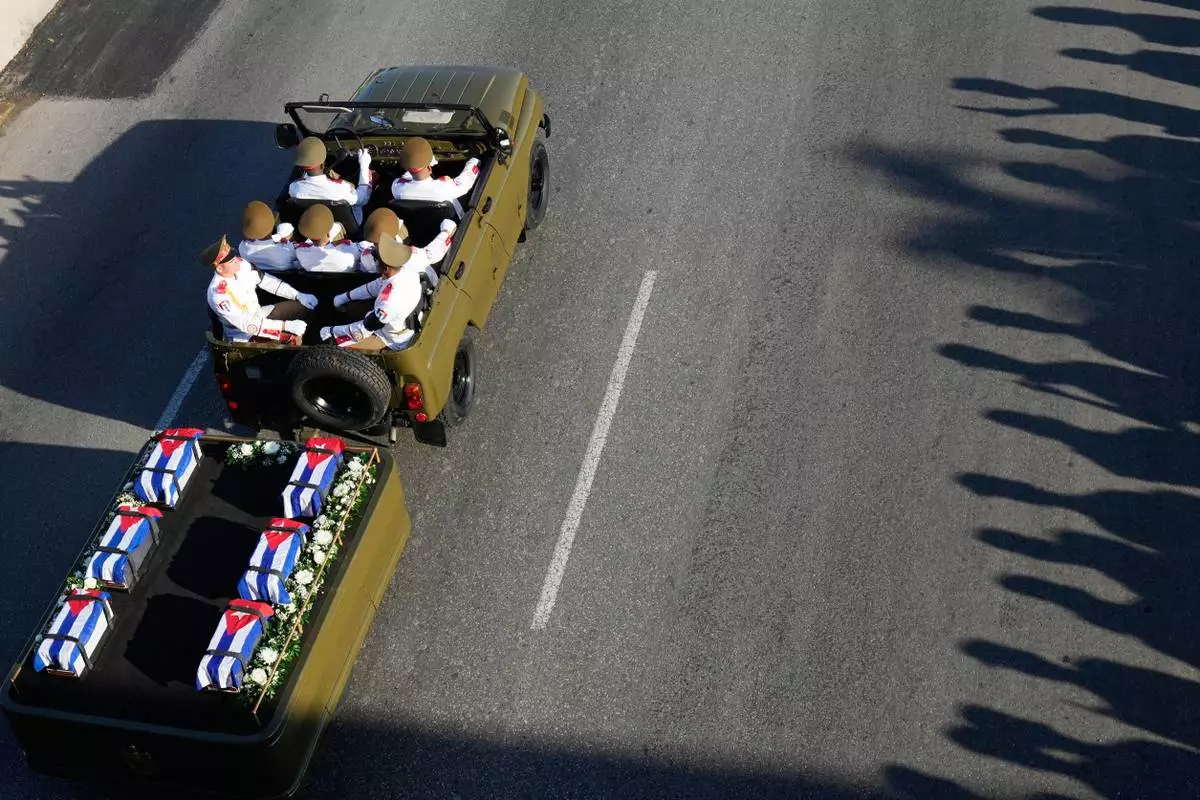

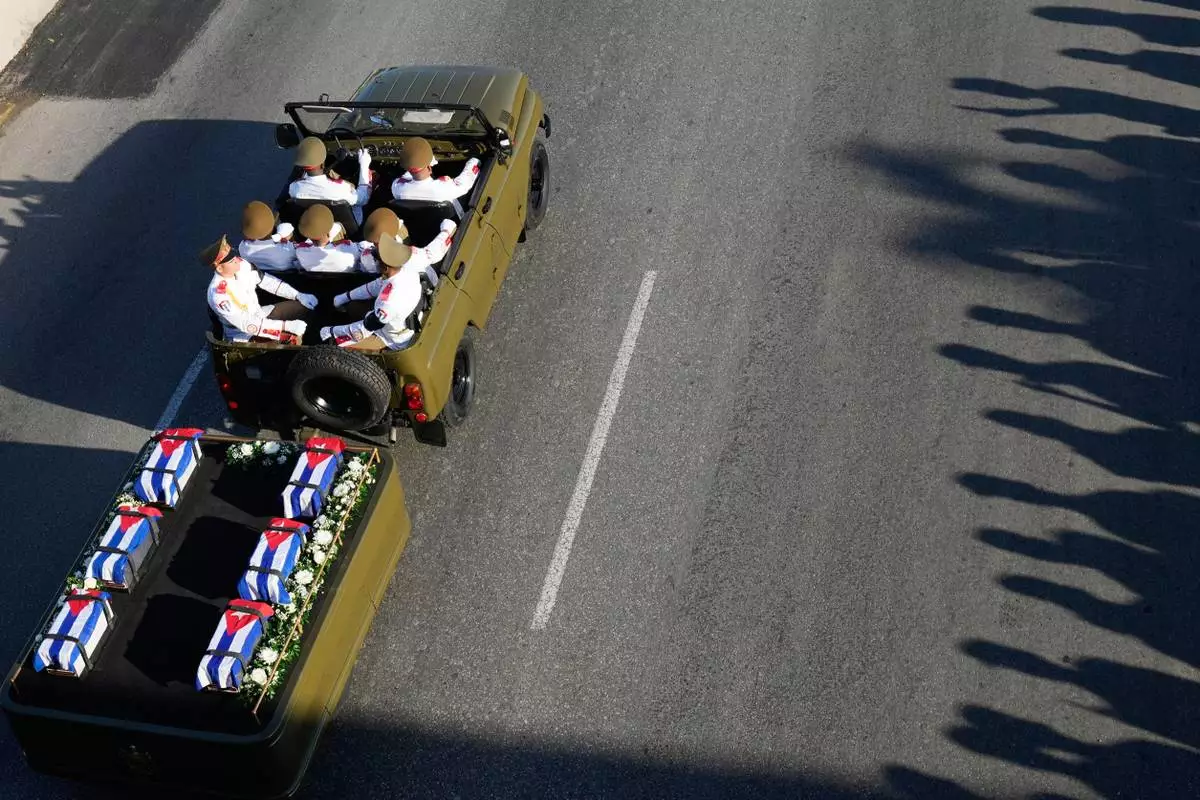

Thousands of Cubans lined a street where motorcycles and military vehicles thundered by with the remains of those killed.

“They are people willing to defend their principles and values, and we must pay tribute to them,” said Carmen Gómez, a 58-year-old industrial designer, adding that she hopes no one invades given the ongoing threats.

When asked why she showed up despite the difficulties Cubans face, Gómez replied, “It’s because of the sense of patriotism that Cubans have, and that will always unite us.”

Cuba recently released the names and ranks of 32 military personnel — ranging in age from 26 to 60 — who were part of the security detail of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro during the raid on his residence on January 3. They included members of the Revolutionary Armed Forces and the Ministry of the Interior, the island’s two security agencies.

Cuban and Venezuelan authorities have said that the uniformed personnel were part of protection agreements between the two countries.

A demonstration was planned for Friday across from the U.S. Embassy in an open-air forum known as the Anti-Imperialist Tribune. Officials have said they expect the demonstration to be massive.

“People are upset and hurt. There’s a lot of talk on social media; but many do believe that the dead are martyrs” of a historic struggle against the United States, analyst and former diplomat Carlos Alzugaray told The Associated Press.

In October 1976, then-President Fidel Castro led a massive demonstration to bid farewell to the 73 people killed in the bombing of a Cubana de Aviación civilian flight financed by anti-revolutionary leaders in the U.S. Most of the victims were Cuban athletes.

In December 1989, officials organized “Operation Tribute” to honor the more than 2,000 Cuban combatants who died in Angola during Cuba’s participation in the war that defeated the South African army and ended the apartheid system. In October 1997, memorial services were held following the arrival of the remains of guerrilla commander Ernesto “Che” Guevara and six of his comrades, who died in 1967.

The latest mass burial is critical to honor those slain, said José Luis Piñeiro, a 60-year-old doctor who lived four years in Venezuela.

“I don’t think Trump is crazy enough to come and enter a country like this, ours, and if he does, he’s going to have to take an aspirin or some painkiller to avoid the headache he’s going to get,” Piñeiro said. “These were 32 heroes who fought him. Can you imagine an entire nation? He’s going to lose.”

A day before the remains of those killed arrived in Cuba, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio announced $3 million in aid to help the island recover from the catastrophic Hurricane Melissa, which struck in late October.

The first flight took off from Florida on Wednesday, and a second flight was scheduled for Friday. A commercial vessel also will deliver food and other supplies.

“We have taken extraordinary measures to ensure that this assistance reaches the Cuban people directly, without interference or diversion by the illegitimate regime,” Rubio said, adding that the U.S. government was working with Cuba's Catholic Church.

The announcement riled Cuban Foreign Minister Bruno Rodríguez.

“The U.S. government is exploiting what appears to be a humanitarian gesture for opportunistic and politically manipulative purposes,” he said in a statement. “As a matter of principle, Cuba does not oppose assistance from governments or organizations, provided it benefits the people and the needs of those affected are not used for political gain under the guise of humanitarian aid.”

Coto contributed from San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Follow AP’s coverage of Latin America and the Caribbean at https://apnews.com/hub/latin-america

Military members pay their last respects to Cuban officers who were killed during the U.S. operation in Venezuela that captured Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, at the Ministry of the Revolutionary Armed Forces where the urns containing the remains are displayed during a ceremony in Havana, Cuba, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026. (AP Photo/Ramon Espinosa)

A motorcade transports urns containing the remains of Cuban officers, who were killed during the U.S. operation in Venezuela that captured Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, through Havana, Cuba, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026. (AP Photo/Ramon Espinosa)

Soldiers carry urns containing the remains of Cuban officers, who were killed during the U.S. operation in Venezuela that captured Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, at the Ministry of the Revolutionary Armed Forces in Havana, Cuba, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026. (Adalberto Roque /Pool Photo via AP)

A motorcade transports urns containing the remains of Cuban officers, who were killed during the U.S. operation in Venezuela that captured Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, through Havana, Cuba, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026. (AP Photo/Ramon Espinosa)

A motorcade transports urns containing the remains of Cuban officers, who were killed during the U.S. operation in Venezuela that captured Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, through Havana, Cuba, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026. (AP Photo/Ramon Espinosa)

People line the streets of Havana, Cuba, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026, to watch the motorcade carrying urns containing the remains of Cuban officers killed during the U.S. operation in Venezuela that captured Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro. (AP Photo/Ramon Espinosa)

Workers fly the Cuban flag at half-staff at the Anti-Imperialist Tribune near the U.S. Embassy in Havana, Cuba, Monday, Jan. 5, 2026, in memory of Cubans who died two days before in Caracas, Venezuela during the capture of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro by U.S. forces. (AP Photo/Ramon Espinosa)