Micky Arison sits courtside, at center court, when his Miami Heat play home games. That's about as much of the spotlight as he wants.

He rarely speaks publicly. He prefers to keep much of what he does and says behind the scenes, instead deferring much of the forward-facing duties to the likes of team president Pat Riley, coach Erik Spoelstra and Heat players. And that's why Arison's enshrinement into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame this weekend is a bit of a double-edged sword for the man who has held the role of Heat managing general partner for the last 30-plus years.

On one hand, it's the greatest individual honor in basketball. On the other, it means he has to make a speech on Saturday night.

“Our goal was to create a fantastic atmosphere in Miami,” Arison said Friday at the Hall of Fame's media circuit, the prelude to the official start of the weekend's festivities. “Most great NBA players, obviously, this is a goal for them. Great coaches, this is a goal for them. It’s never been a goal for me. Despite that, I’m extremely appreciative and recognize that it’s a tremendous honor.”

The hesitation about taking a public bow makes sense, if one knows much about Arison. His father, Carnival Cruise Line founder Ted Arison, was one of the biggest keys to Miami getting an NBA franchise in the first place. When the idea was discussed within the family, Micky Arison recommended that his father not get involved with sports. His thinking was simple: Ted Arison had already built a wildly successful cruise line, so why would he want to instead become known as the guy who drafted the wrong player or executed a bad trade?

Ted Arison didn't listen and got involved anyway. Micky Arison assumed full control of the team in 1995 and hired Riley a few months later. After 30 years and three championships, the Hall of Fame called.

"When he bought the interest in the Heat in 1995 and got managing control of the Heat, that’s the day that the franchise took a turn," Riley said. “And unbeknownst to a lot of people, they didn’t know what kind of turn it was going to be. But that’s the day that the franchise began to move in another direction. He saved, basically, my coaching life, I think."

The turn that the Heat took under Arison was a great one. Over his 30 years in charge, the Heat have the three titles, seven Eastern Conference titles and the third-best record in the NBA over that span — behind only San Antonio and the Los Angeles Lakers.

“Micky is one of the great human beings," said longtime Duke coach Mike Krzyzewski, a fellow Hall of Famer and someone who had Nick Arison — Micky's son, and now the Heat CEO — with him at Duke as a manager.

“You know, I’ve been fortunate to be a friend of Micky's for decades now,” Krzyzewski said. "The class, the dignity and the humility that he has shown throughout ... what a deserving honor for him. He's touched a lot of people in magnificent ways and without wanting anything in return. He's just a great human being. I respect the heck out of him.”

Arison is going into the Hall of Fame this weekend as part of a class that also includes the 2008 U.S. Olympic basketball team that Krzyzewski coached, Sue Bird, Maya Moore, Sylvia Fowles, Billy Donovan, Dwight Howard, Carmelo Anthony and Dan Crawford.

Arison will be presented for his induction at Springfield, Massachusetts, on Saturday night by Riley, Alonzo Mourning — a Heat player and now longtime team executive — and Dwyane Wade, a trio of Heat legends who were previously enshrined in the Hall of Fame. They'll be with him when he gives his speech.

Choosing them to be there for that moment, Arison said, was easy.

“They were three key elements to the history, to 30 years," Arison said. "Obviously, Pat was with me from almost the very beginning. Zo, the first year. And really from there, the culture was created. And Dwyane Wade helped take it to the top and has been obviously the greatest player in Heat history with a statue on the top of the steps (of the team's arena). I’m glad those three will be with me.”

AP NBA: https://apnews.com/hub/nba

FILE - Micky Arison speaks during a Naismith Hall Fame Class of 2025 inductee news conference at the Final Four of the NCAA college basketball tournament, April 5, 2025, in San Antonio. (AP Photo/David J. Phillip)

MADRID (AP) — Venezuelans living in Spain are watching the events unfold back home with a mix of awe, joy and fear.

Some 600,000 Venezuelans live in Spain, home to the largest population anywhere outside the Americas. Many fled political persecution and violence but also the country’s collapsing economy.

A majority live in the capital, Madrid, working in hospitals, restaurants, cafes, nursing homes and elsewhere. While some Venezuelan migrants have established deep roots and lives in the Iberian nation, others have just arrived.

Here is what three of them had to say about the future of Venezuela since U.S. forces deposed Nicolás Maduro.

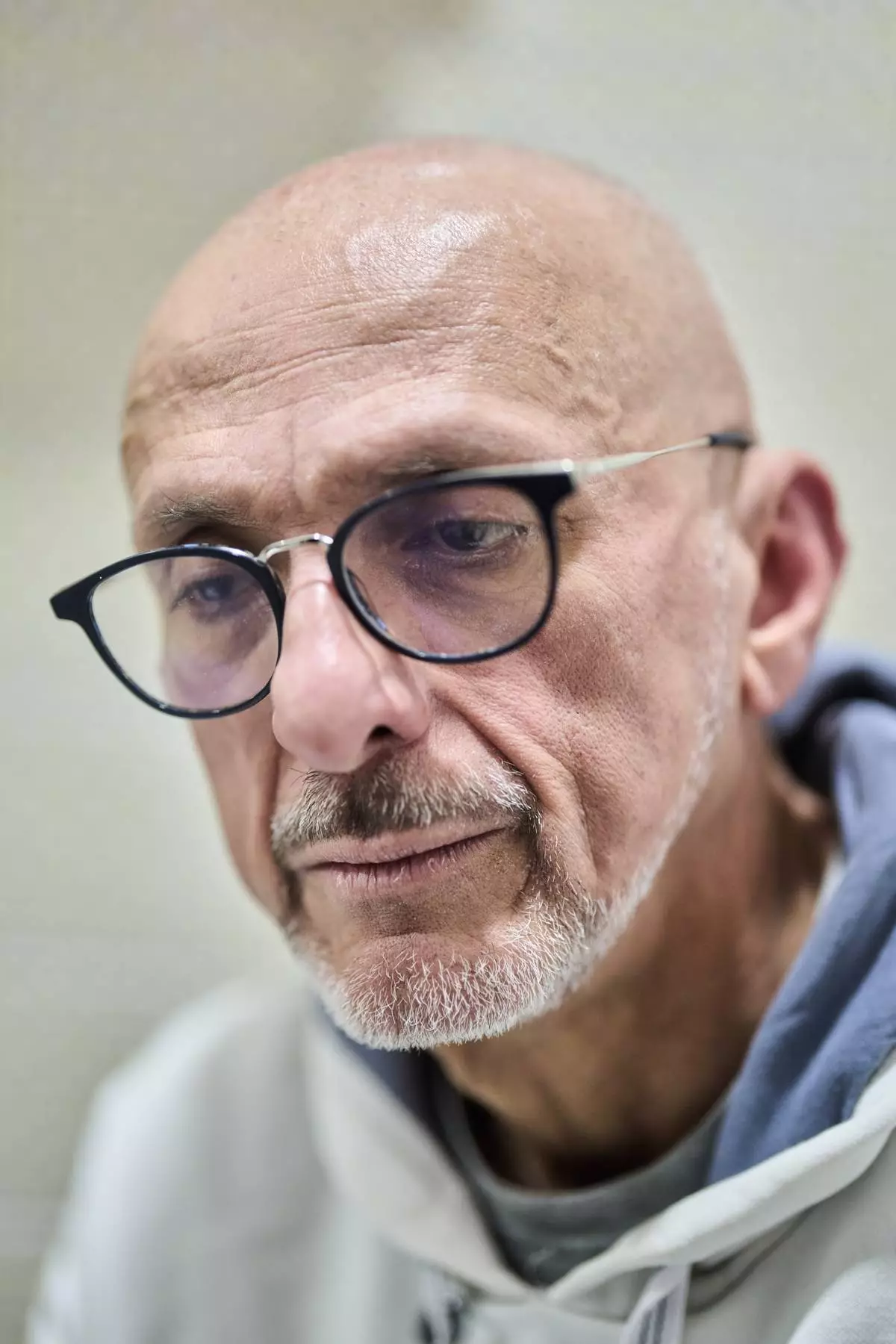

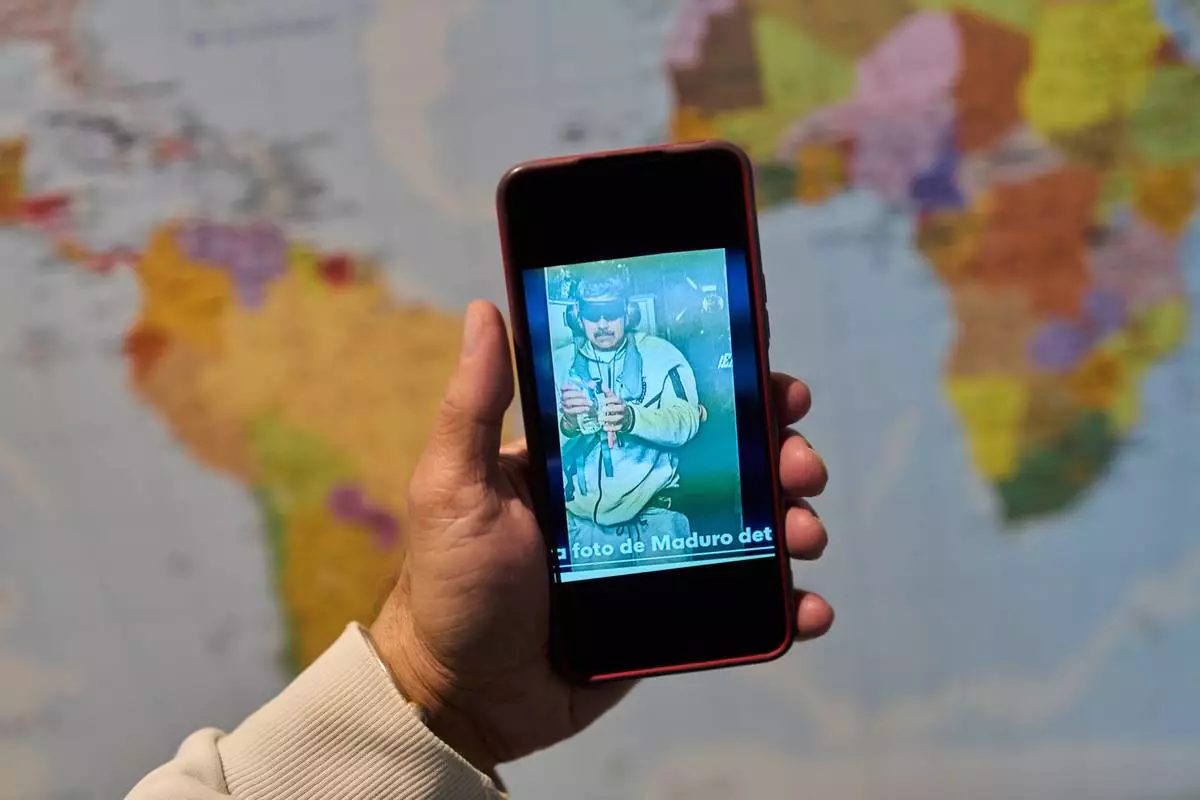

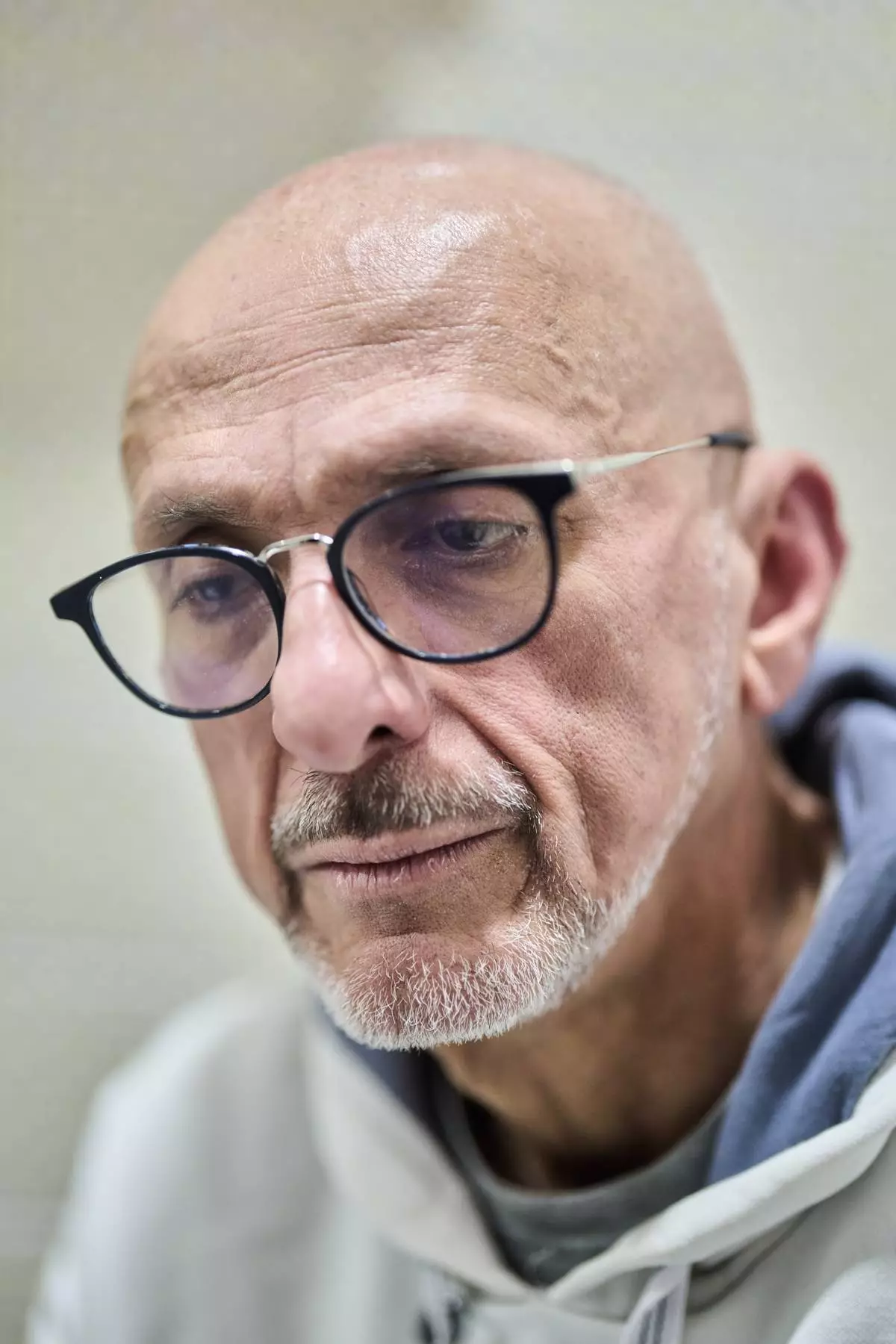

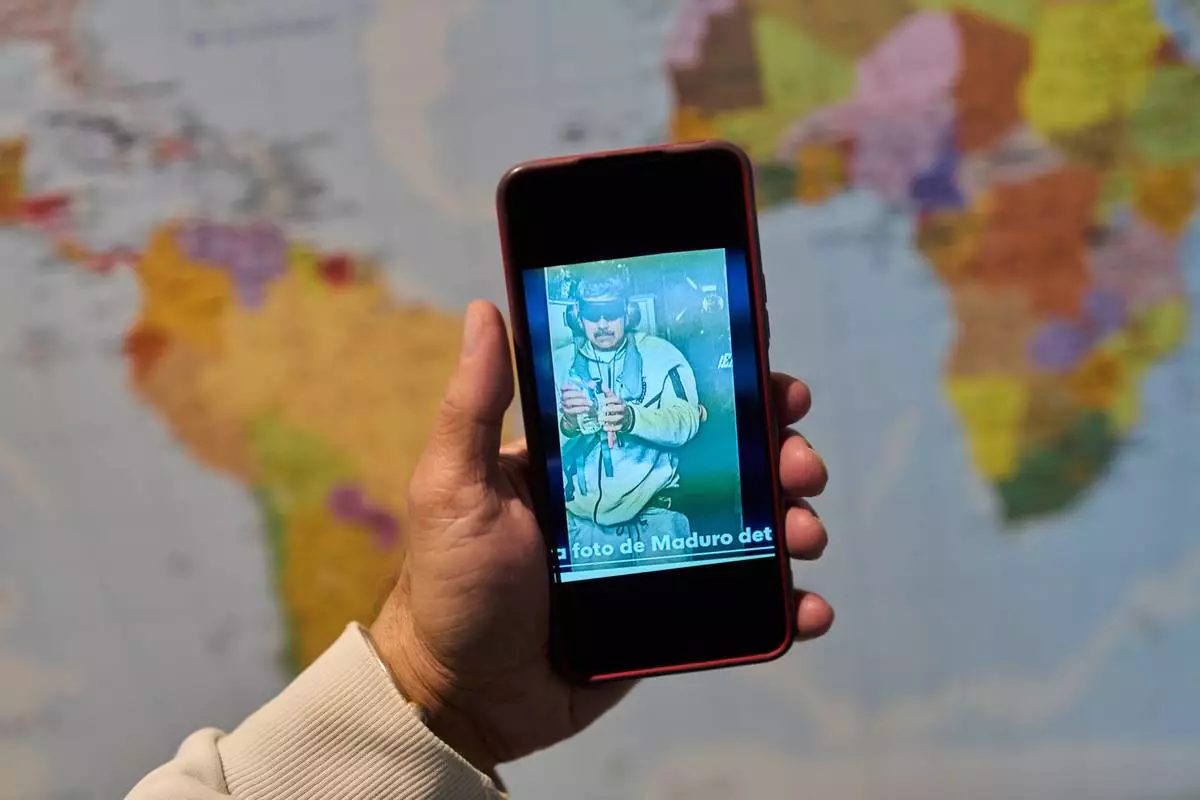

David Vallenilla woke up to text messages from a cousin on Jan. 3 informing him “that they invaded Venezuela.” The 65-year-old from Caracas lives alone in a tidy apartment in the south of Madrid with two Daschunds and a handful of birds. He was in disbelief.

“In that moment, I wanted certainty,” Vallenilla said, “certainty about what they were telling me.”

In June 2017, Vallenilla’s son, a 22-year-old nursing student in Caracas named David José, was shot point-blank by a Venezuelan soldier after taking part in a protest near a military air base in the capital. He later died from his injuries. Video footage of the incident was widely publicized, turning his son’s death into an emblematic case of the Maduro government’s repression against protesters that year.

After demanding answers for his son’s death, Vallenilla, too, started receiving threats and decided two years later to move to Spain with the help of a nongovernmental organization.

On the day of Maduro’s capture, Vallenilla said his phone was flooded with messages about his son.

“Many told me, ‘Now David will be resting in peace. David must be happy in heaven,’” he said. “But don't think it was easy: I spent the whole day crying.”

Vallenilla is watching the events in Venezuela unfold with skepticism but also hope. He fears more violence, but says he has hope the Trump administration can effect the change that Venezuelans like his son tried to obtain through elections, popular protests and international institutions.

“Nothing will bring back my son. But the fact that some justice has begun to be served for those responsible helps me see a light at the end of the tunnel. Besides, I also hope for a free Venezuela.”

Journalist Carleth Morales first came to Madrid a quarter-century ago when Hugo Chávez was reelected as Venezuela's president in 2000 under a new constitution.

The 54-year-old wanted to study and return home, taking a break of sorts in Madrid as she sensed a political and economic environment that was growing more and more challenging.

“I left with the intention of getting more qualified, of studying, and of returning because I understood that the country was going through a process of adaptation between what we had known before and, well, Chávez and his new policies," Morales said. "But I had no idea that we were going to reach the point we did.”

In 2015, Morales founded an organization of Venezuelan journalists in Spain, which today has hundreds of members.

The morning U.S. forces captured Maduro, Morales said she woke up to a barrage of missed calls from friends and family in Venezuela.

“Of course, we hope to recover a democratic country, a free country, a country where human rights are respected,” Morales said. “But it’s difficult to think that as a Venezuelan when we’ve lived through so many things and suffered so much.”

Morales sees it as unlikely that she would return home, having spent more than two decades in Spain, but she said she hopes her daughters can one day view Venezuela as a viable option.

“I once heard a colleague say, ‘I work for Venezuela so that my children will see it as a life opportunity.’ And I adopted that phrase as my own. So perhaps in a few years it won’t be me who enjoys a democratic Venezuela, but my daughters.”

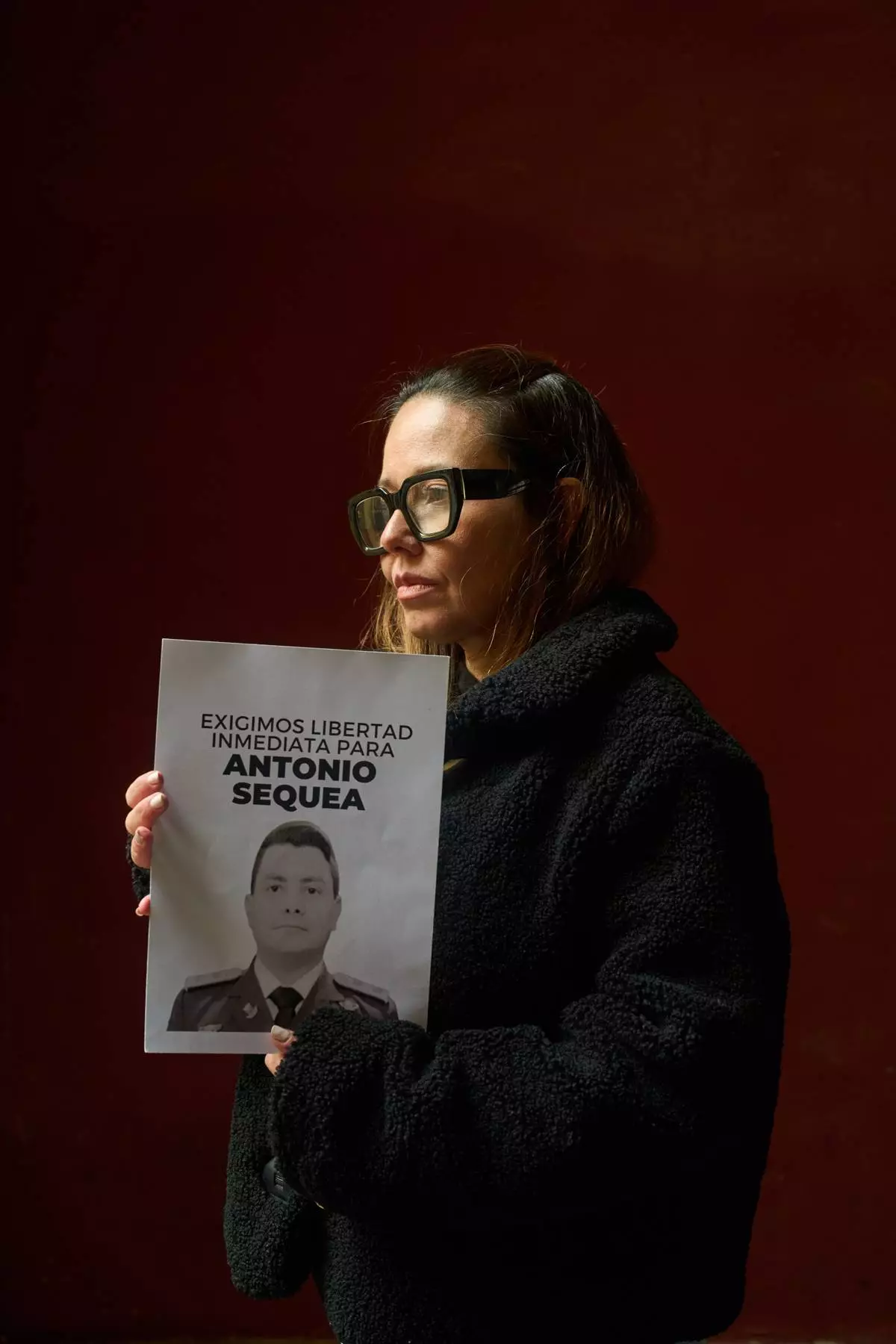

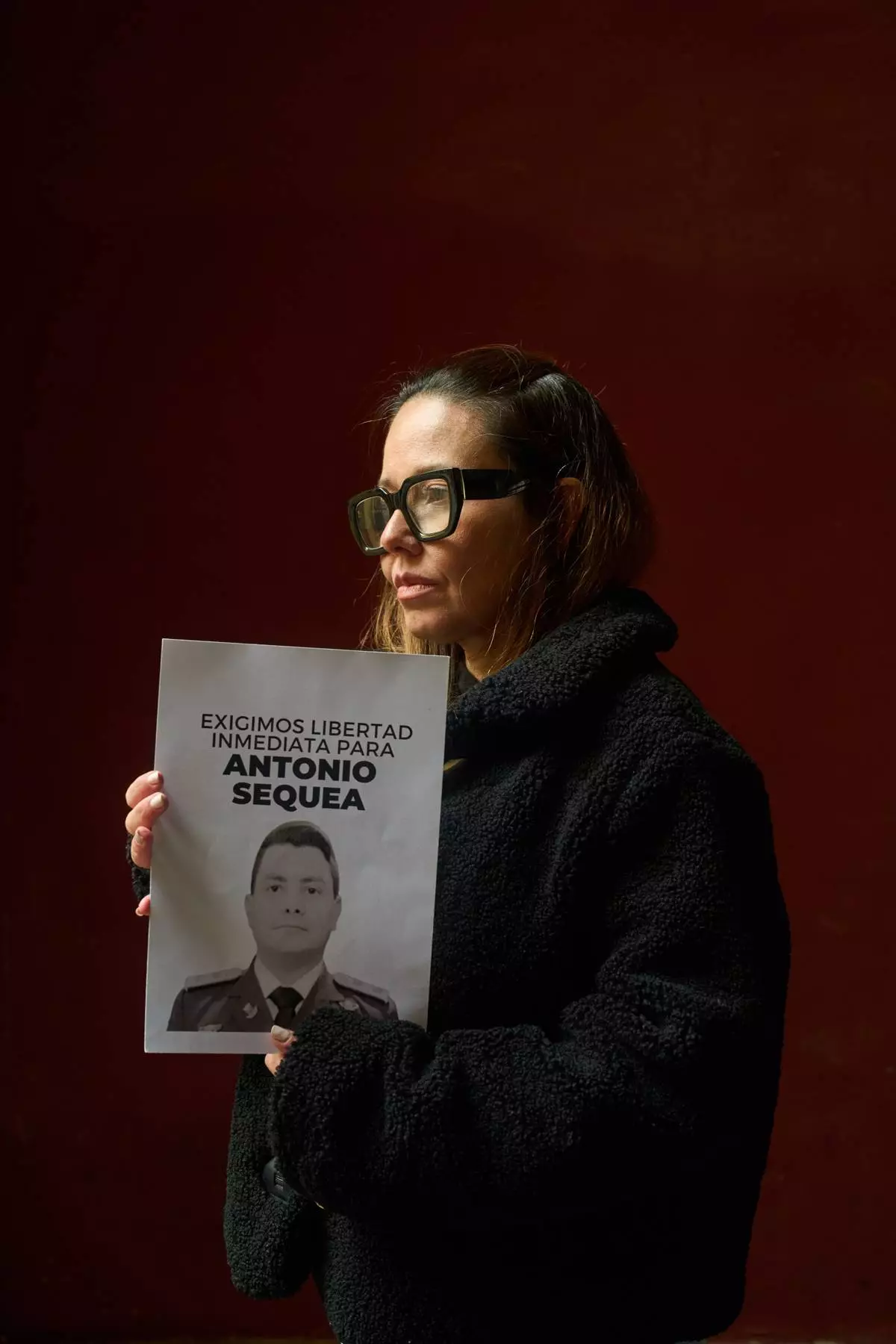

For two weeks, Verónica Noya has waited for her phone to ring with the news that her husband and brother have been freed.

Noya’s husband, Venezuelan army Capt. Antonio Sequea, was imprisoned in 2020 after having taken part in a military incursion to oust Maduro. She said he remains in solitary confinement in the El Rodeo prison in Caracas. For 20 months, Noya has been unable to communicate with him or her brother, who was also arrested for taking part in the same plot.

“That’s when my nightmare began,” Noya said.

Venezuelan authorities have said hundreds of political prisoners have been released since Maduro's capture, while rights groups have said the real number is a fraction of that. Noya has waited in agony to hear anything about her four relatives, including her husband's mother, who remain imprisoned.

Meanwhile, she has struggled with what to tell her children when they ask about their father's whereabouts. They left Venezuela scrambling and decided to come to Spain because family roots in the country meant that Noya already had a Spanish passport.

Still, she hopes to return to her country.

“I’m Venezuelan above all else,” Noya said. “And I dream of seeing a newly democratic country."

Venezuelan journalist Caleth Morales works in her apartment's kitchen in Madrid, Wednesday, Jan. 14, 2026. (AP Photo/Bernat Armangue)

David Vallenilla, father of the late David José Vallenilla Luis, sits in his apartment's kitchen in Madrid, Tuesday, Jan. 13, 2026. (AP Photo/Bernat Armangue)

Veronica Noya holds a picture of her husband Antonio Sequea in Madrid, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026. (AP Photo/Bernat Armangue)

David Vallenilla holds a picture of deposed President Nicolas Maduro, blindfolded and handcuffed, during an interview with The Associated Press at his home in Madrid, Tuesday, Jan. 13, 2026. (AP Photo/Bernat Armangue)

Pictures of the late David José Vallenilla Luis are placed in the living room of his father, David José Vallenilla, in Madrid, Tuesday, Jan. 13, 2026. (AP Photo/Bernat Armangue)