NEW YORK (AP) — When the winning run scored in Game 6 of the 1986 World Series, the New York Mets melted into a white-and-blue swirl near home plate, celebrating their implausible comeback from the brink of defeat.

Right in the middle of all that humanity was Davey Johnson, who had arrived at the mob scene before many of his players.

Click to Gallery

FILE - New York Gov. Mario Cuomo, left, New York Mets Manager Davey Johnson, center, and New York Mayor Ed Koch, raise their hands signaling "number one" during a tickertape parade for the World Series winners in downtown Manhattan, New York, Oct. 28, 1986, in New York. (AP Photo/Mario Cabrera, File)

FILE - New York Mets Manager Davey Johnson, center, holds baseball's World Series trophy on the podium after the Mets defeated the Boston Red Sox in Game 7, at Shea Stadium in New York, Oct. 27, 1986. Mets General Manager Frank Cashen, left, Baseball Commissioner Peter Ueberroth, partially hidden, and Mets President Fred Wilpon, right, join the celebration in the locker room the clubhouse. (AP Photo/Ray Stubblebine, File)

FILE - New York Gov. Mario Cuomo, left, New York Mets Manager Davey Johnson, center, and New York Mayor Ed Koch, raise their hands signaling "number one" during a tickertape parade for the World Series winners in downtown Manhattan, New York, Oct. 28, 1986, in New York. (AP Photo/Mario Cabrera, File)

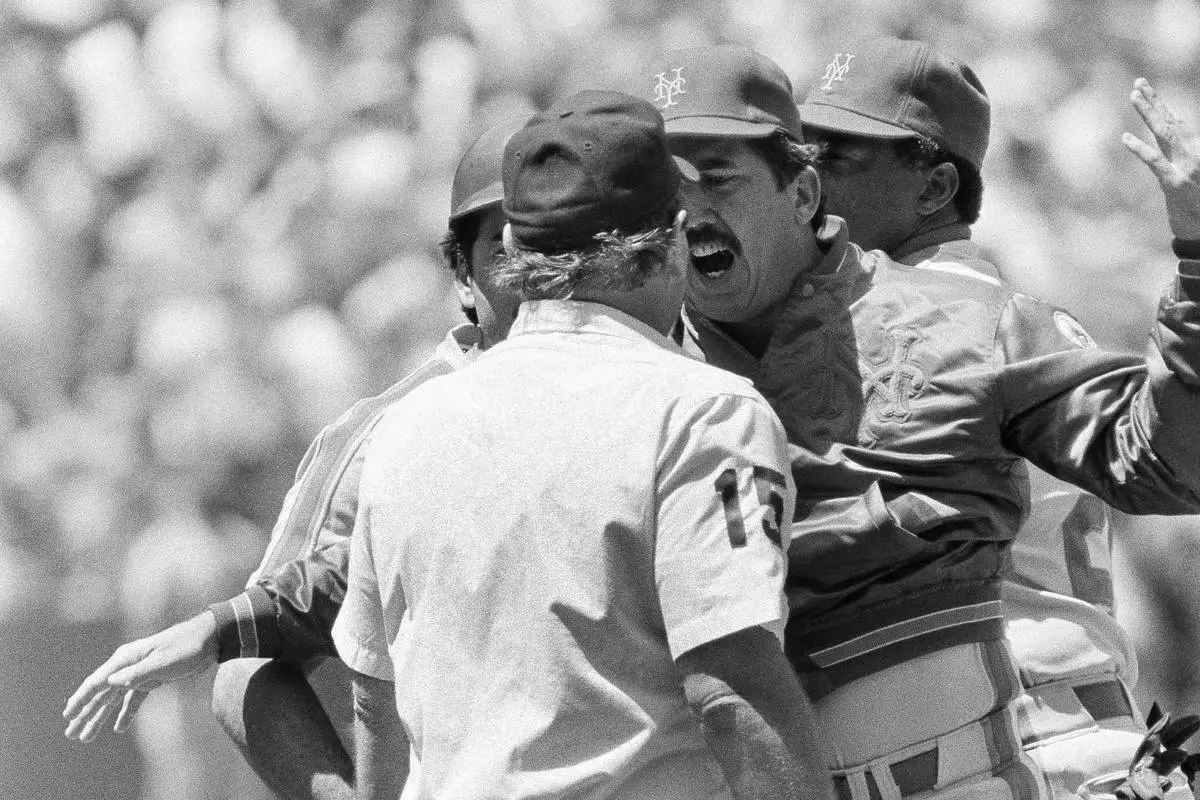

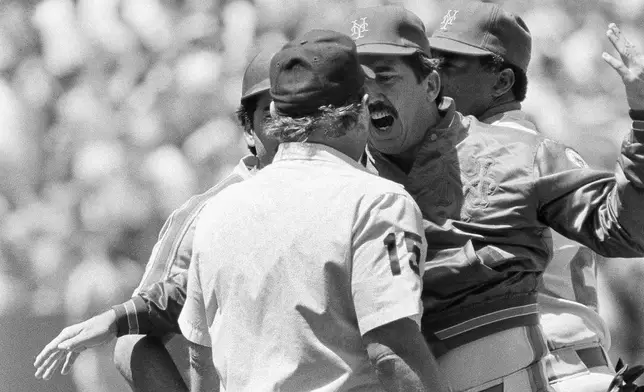

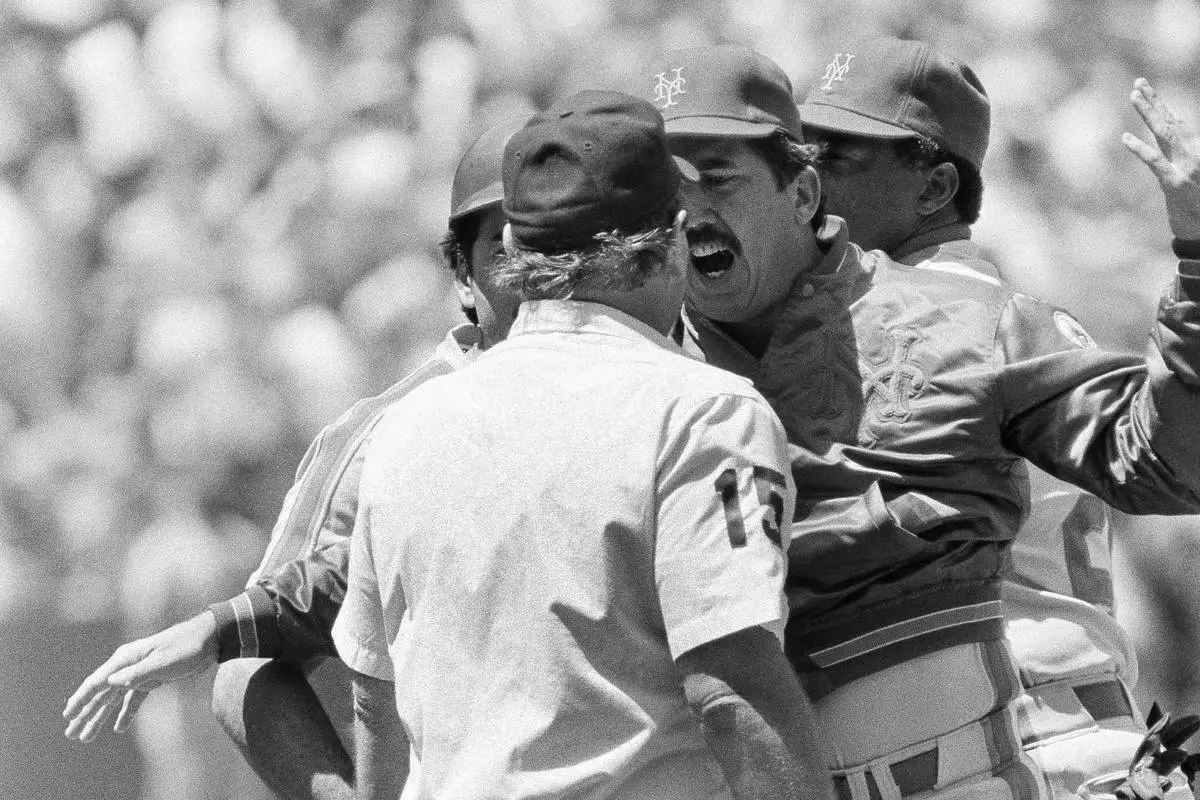

FILE - New York Mets' manager Davey Johnson argues with home plate umpire Jim Quick after Mets' Keith Hernandez was ejected after arguing over a strike three call in the eighth inning of a baseball game against the San Francisco Giants,, May 30, 1985 at Candlestick Park in San Francisco. (AP Photo/Paul Sakuma, File)

FILE - New York Mets Manager Davey Johnson, center, holds baseball's World Series trophy on the podium after the Mets defeated the Boston Red Sox in Game 7, at Shea Stadium in New York, Oct. 27, 1986. Mets General Manager Frank Cashen, left, Baseball Commissioner Peter Ueberroth, partially hidden, and Mets President Fred Wilpon, right, join the celebration in the locker room the clubhouse. (AP Photo/Ray Stubblebine, File)

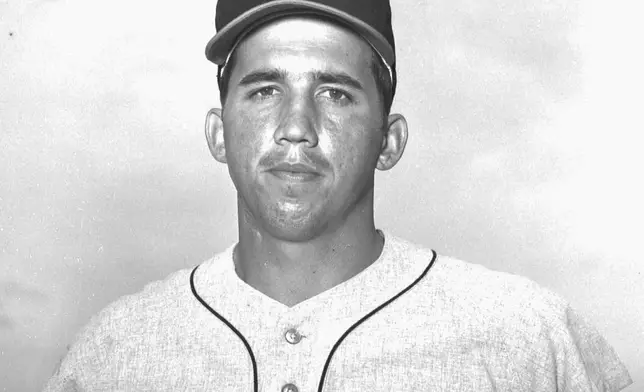

FILE-- Baltimore Orioles manager Davey Johnson, shown in this 1969 file photo. (AP Photo/File)

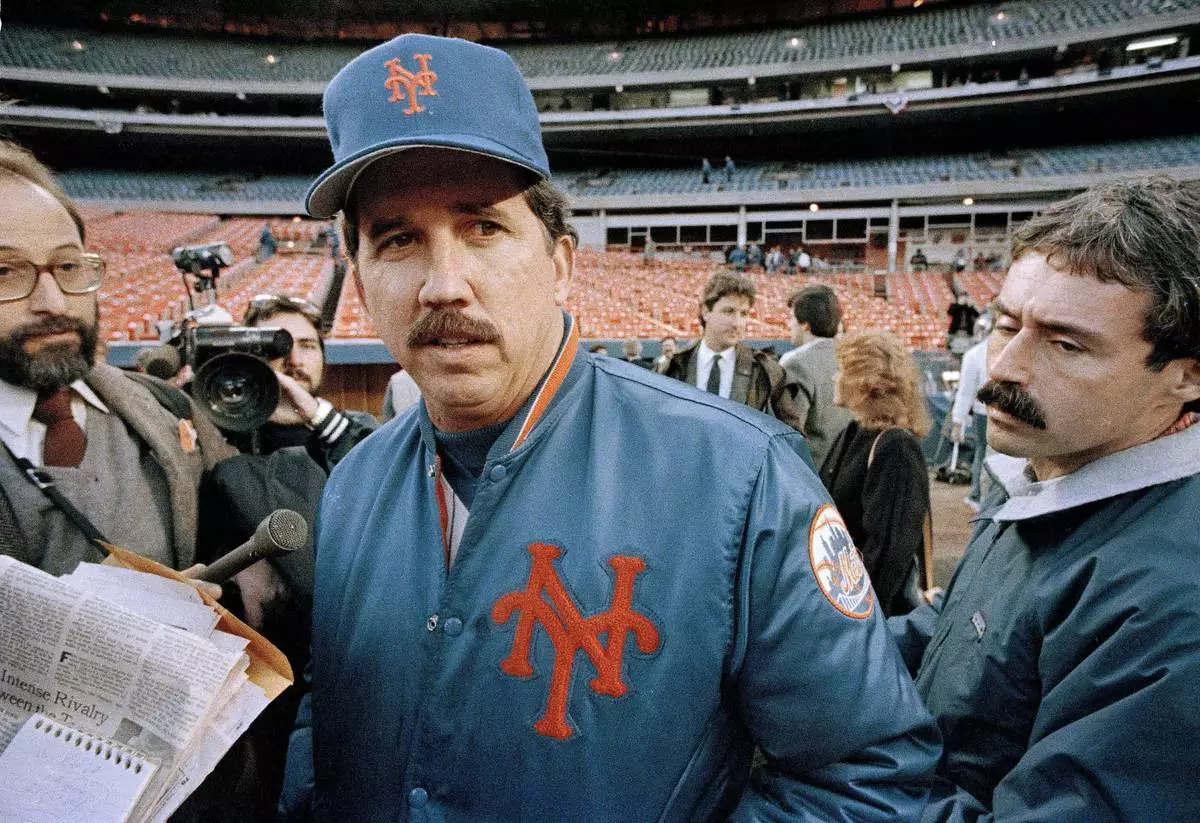

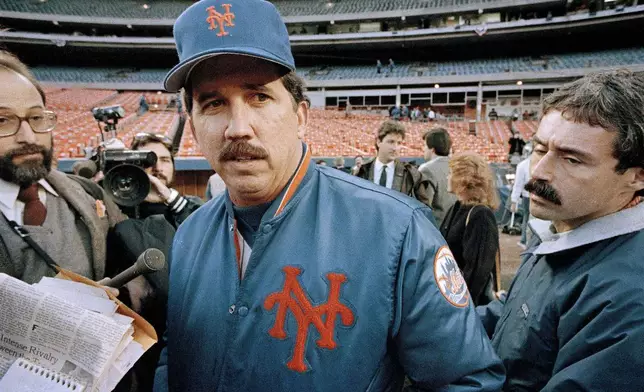

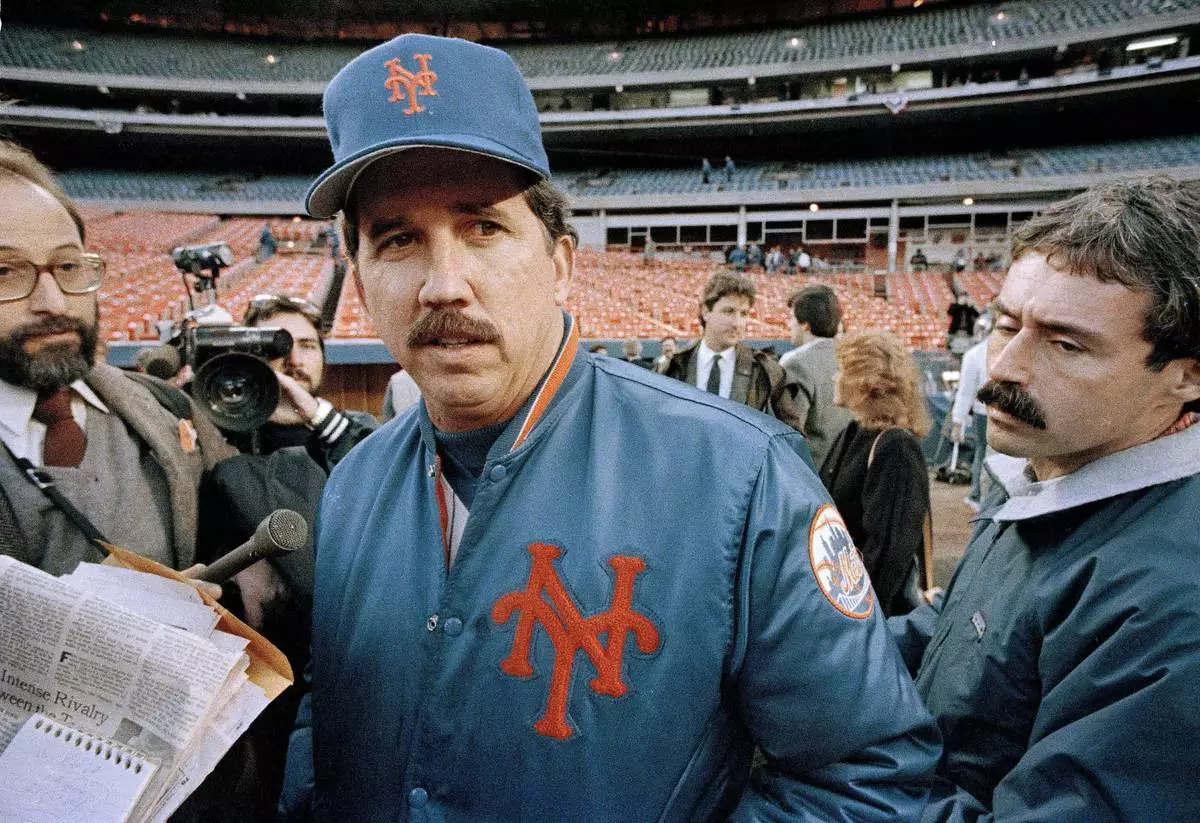

FILE - New York Mets Manager Davey Johnson speaks to reporters after game 7 of the World Series was postponed a day due to rain, in New York, Oct. 26, 1986. (AP Photo/Richard Drew, File)

FILE - New York Mets Manager Davey Johnson talks with reporters prior to the opening game of the World Series between the Mets and the Boston Red Sox at Shea Stadium in New York, Oct. 18, 1986. (AP Photo/Paul Bemoit, File)

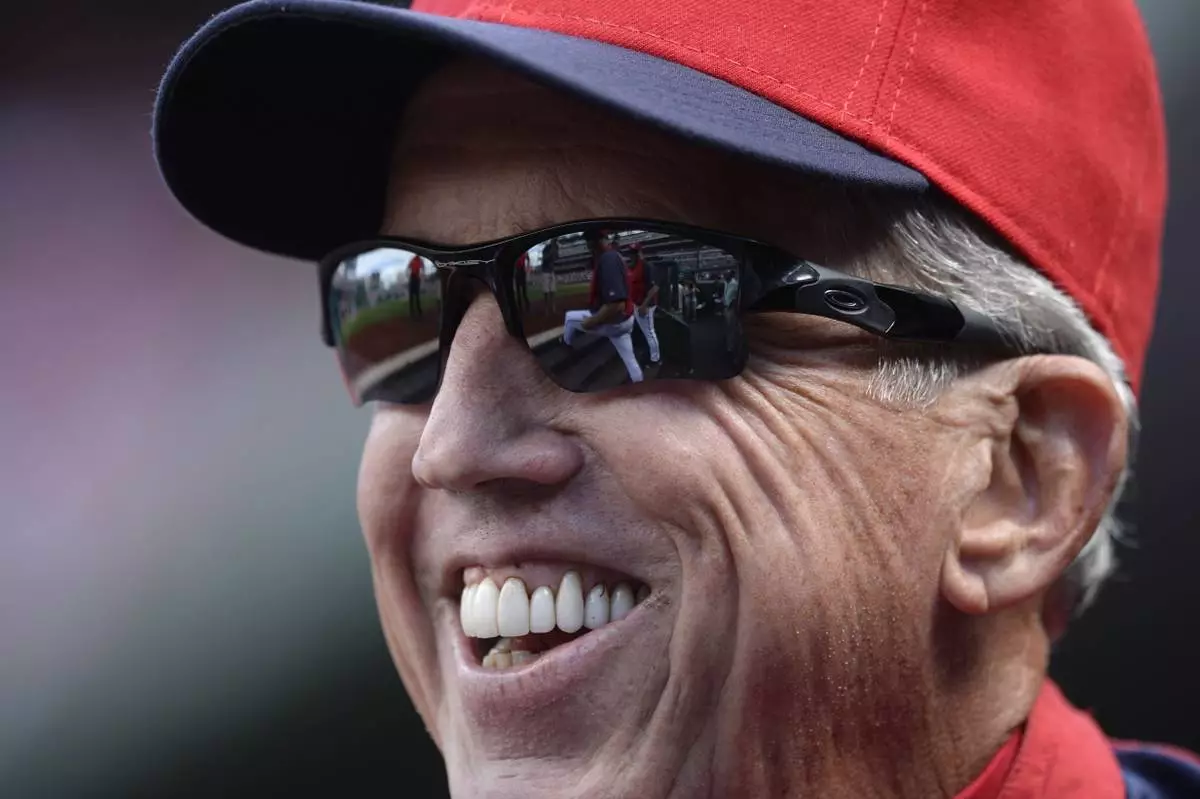

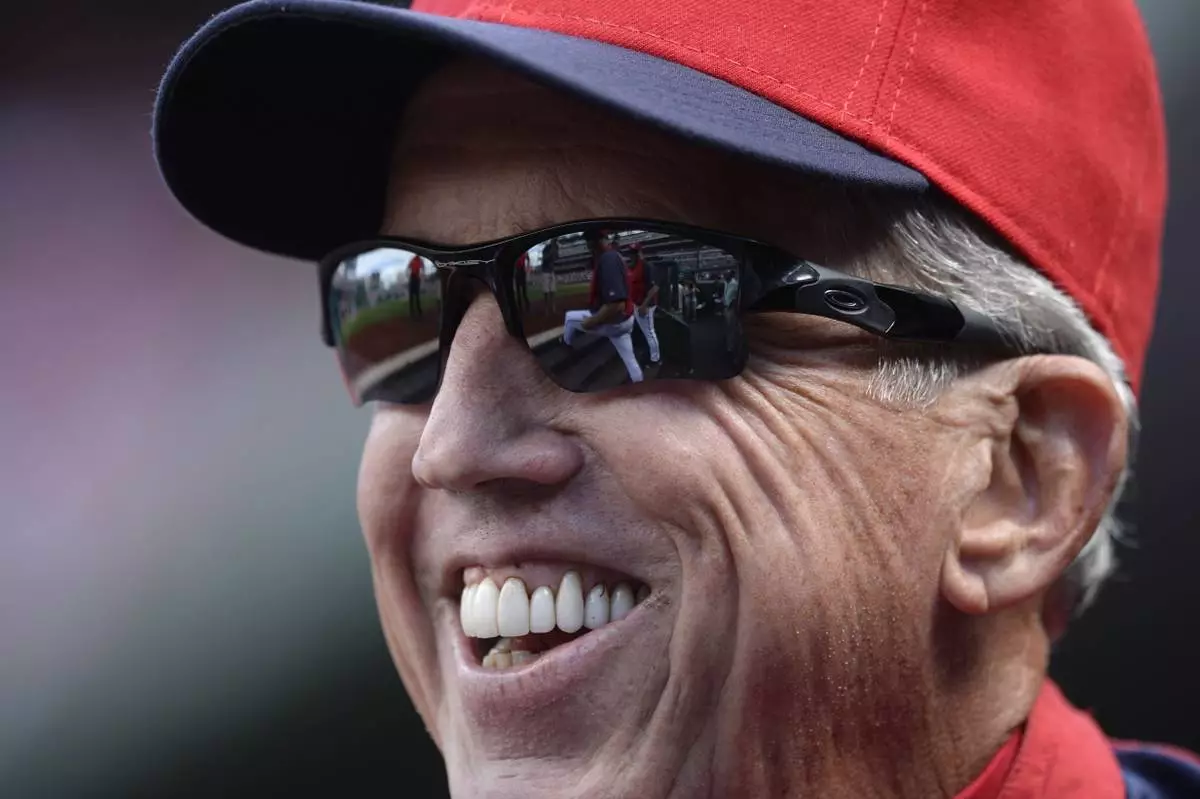

FILE - Washington National manager Davey Johnson laughs before a baseball game against the Miami Marlins at Nationals Park in Washington, Sunday, Sept. 22, 2013. (AP Photo/Susan Walsh, File)

Those '86 Mets — with all their brashness, belligerence and unapologetic brilliance — would not have been the same without their 43-year-old manager.

Johnson died Friday at age 82. Longtime Mets public relations representative Jay Horwitz said Johnson's wife Susan informed him of his death after a long illness. Johnson was at a hospital in Sarasota, Florida.

“His ability to empower players to express themselves while maintaining a strong commitment to excellence was truly inspiring,” Darryl Strawberry posted on Instagram with a photo of him, Johnson and Dwight Gooden. “Davey’s legacy will forever be etched in the hearts of fans and players alike."

Strawberry and Gooden were the young stars of that 1986 team, and their talent and off-field troubles came to symbolize an era of Mets baseball. It was Johnson's third World Series title after he won two as a player with the Baltimore Orioles.

A four-time All-Star, Johnson played 13 major league seasons with Baltimore, the Atlanta Braves, Philadelphia Phillies and Chicago Cubs from 1965-78 and won three Gold Gloves at second base. He managed the Mets, Cincinnati Reds, Los Angeles Dodgers and Washington Nationals during a span from 1984-2013.

“Davey was a good man, close friend and a mentor,” former Nationals general manager Mike Rizzo said in a text message. “A Hall of Fame caliber manager with a baseball mind ahead of his time.”

Born Jan. 30, 1943, in Orlando, Florida, Johnson won World Series titles with the Orioles in 1966 and 1970 and also made the final out of the 1969 Fall Classic against the Mets — an irony given his future role with them. In 1973, Johnson hit a career-high 43 home runs with the Braves, joining Darrell Evans (41) and Henry Aaron (40) as part of the first trio of teammates in major league history to reach 40 in the same year.

Johnson's first managerial job was with the Mets when he was in his early 40s. In steering that famously rowdy group to a title in '86, he earned a reputation for giving his players their freedom. When that team began to decline, he was fired in 1990, but his days as a manager were far from over.

Johnson's tenure in Cincinnati ended unusually. He was a lame duck at the start of the 1995 season, with Reds owner Marge Schott prepared to give Ray Knight — the man who scored that winning run in Game 6 for the Mets in ‘86 — the managing job once that season was over. After guiding Cincinnati to a division title in ’95, Johnson went back to Baltimore to manage the Orioles.

"Davey Johnson was one of the best managers I ever had the privilege of working with in my career," Jim Bowden, Cincinnati's general manager that year, said on social media Saturday. “He taught me so much about baseball specifically how to build bullpens, develop young pitchers and put together elite coaching staffs. He was a brilliant, kind leader and teammate.”

When Johnson took over the Orioles, he had enough credibility to move Cal Ripken Jr. from shortstop to third base, and Baltimore made the playoffs each of his two seasons at the helm. It was the first time the Orioles had done so since 1983, and they wouldn't qualify again until 2012.

Like in Cincinnati, Johnson won a division title in what turned out to be the last year of his tenure in Baltimore. Amid a feud with owner Peter Angelos, Johnson resigned after the 1997 season — hours after receiving his first Manager of the Year award.

He won it again in 2012, when he led the Nationals to baseball's best regular-season record and the franchise's first postseason spot since moving from Montreal to Washington.

“Davey was a world-class manager,” Nationals owner Mark Lerner said in a statement. “I’ll always cherish the memories we made together with the Nationals, and I know his legacy will live on in the heads and minds of our fans and those across baseball.”

Johnson studied math at Trinity University in Texas, and he had an innovative side. Even when he was a player, he was already using data to try to optimize the Orioles' lineup, although Hall of Fame manager Earl Weaver wasn't turning that duty over to his infielder.

But when dealing with his own players as a manager, Johnson had a blunt, old-school manner, according to Mike Bordick, Baltimore's shortstop in 1997.

“He was so easy to play for,” Bordick said. “He just knew the right buttons to push.”

Ryan Zimmerman, who played for Johnson with Washington from 2011-13, said Johnson was an even better human than he was a baseball man.

“He knew how to get the best out of everyone — on and off the field,” Zimmerman said in a text message. “I learned so much from him, and my career would not have been the same without my years with him. He will be deeply missed by so many people.”

AP National Writer Howard Fendrich contributed to this report. Noah Trister reported from Baltimore.

AP MLB: https://apnews.com/hub/mlb

FILE - New York Gov. Mario Cuomo, left, New York Mets Manager Davey Johnson, center, and New York Mayor Ed Koch, raise their hands signaling "number one" during a tickertape parade for the World Series winners in downtown Manhattan, New York, Oct. 28, 1986, in New York. (AP Photo/Mario Cabrera, File)

FILE - New York Mets' manager Davey Johnson argues with home plate umpire Jim Quick after Mets' Keith Hernandez was ejected after arguing over a strike three call in the eighth inning of a baseball game against the San Francisco Giants,, May 30, 1985 at Candlestick Park in San Francisco. (AP Photo/Paul Sakuma, File)

FILE - New York Mets Manager Davey Johnson, center, holds baseball's World Series trophy on the podium after the Mets defeated the Boston Red Sox in Game 7, at Shea Stadium in New York, Oct. 27, 1986. Mets General Manager Frank Cashen, left, Baseball Commissioner Peter Ueberroth, partially hidden, and Mets President Fred Wilpon, right, join the celebration in the locker room the clubhouse. (AP Photo/Ray Stubblebine, File)

FILE-- Baltimore Orioles manager Davey Johnson, shown in this 1969 file photo. (AP Photo/File)

FILE - New York Mets Manager Davey Johnson speaks to reporters after game 7 of the World Series was postponed a day due to rain, in New York, Oct. 26, 1986. (AP Photo/Richard Drew, File)

FILE - New York Mets Manager Davey Johnson talks with reporters prior to the opening game of the World Series between the Mets and the Boston Red Sox at Shea Stadium in New York, Oct. 18, 1986. (AP Photo/Paul Bemoit, File)

FILE - Washington National manager Davey Johnson laughs before a baseball game against the Miami Marlins at Nationals Park in Washington, Sunday, Sept. 22, 2013. (AP Photo/Susan Walsh, File)

PARIS (AP) — Brigitte Bardot, the French 1960s sex symbol who became one of the greatest screen sirens of the 20th century and later a militant animal rights activist and far-right supporter, has died. She was 91.

Bardot died Sunday at her home in southern France, according to Bruno Jacquelin, of the Brigitte Bardot Foundation for the protection of animals. Speaking to The Associated Press, he gave no cause of death, and said no arrangements have yet been made for funeral or memorial services. She had been hospitalized last month.

Bardot became an international celebrity as a sexualized teen bride in the 1956 movie “And God Created Woman.” Directed by her then-husband, Roger Vadim, it triggered a scandal with scenes of the long-legged beauty dancing on tables naked.

At the height of a cinema career that spanned some 28 films and three marriages, Bardot came to symbolize a nation bursting out of bourgeois respectability. Her tousled, blond hair, voluptuous figure and pouty irreverence made her one of France’s best-known stars.

Such was her widespread appeal that in 1969 her features were chosen to be the model for “Marianne,” the national emblem of France and the official Gallic seal. Bardot’s face appeared on statues, postage stamps and even on coins.

‘’We are mourning a legend,'' French President Emmanuel Macron wrote Sunday on X.

Bardot’s second career as an animal rights activist was equally sensational. She traveled to the Arctic to blow the whistle on the slaughter of baby seals; she condemned the use of animals in laboratory experiments; and she opposed Muslim slaughter rituals.

“Man is an insatiable predator,” Bardot told The Associated Press on her 73rd birthday, in 2007. “I don’t care about my past glory. That means nothing in the face of an animal that suffers, since it has no power, no words to defend itself.”

Her activism earned her compatriots’ respect and, in 1985, she was awarded the Legion of Honor, the nation’s highest recognition.

Later, however, she fell from public grace as her animal protection diatribes took on a decidedly extremist tone. She frequently decried the influx of immigrants into France, especially Muslims.

She was convicted and fined five times in French courts of inciting racial hatred, in incidents inspired by her opposition to the Muslim practice of slaughtering sheep during annual religious holidays.

Bardot’s 1992 marriage to fourth husband Bernard d’Ormale, a onetime adviser to National Front leader Jean-Marie Le Pen, contributed to her political shift. She described Le Pen, an outspoken nationalist with multiple racism convictions of his own, as a “lovely, intelligent man.”

In 2012, she wrote a letter in support of the presidential bid of Marine Le Pen, who now leads her father's renamed National Rally party. Le Pen paid homage Sunday to an “exceptional woman” who was “incredibly French.”

In 2018, at the height of the #MeToo movement, Bardot said in an interview that most actors protesting sexual harassment in the film industry were “hypocritical” and “ridiculous” because many played “the teases” with producers to land parts.

She said she had never had been a victim of sexual harassment and found it “charming to be told that I was beautiful or that I had a nice little ass.”

Brigitte Anne-Marie Bardot was born Sept. 28, 1934, to a wealthy industrialist. A shy, secretive child, she studied classical ballet and was discovered by a family friend who put her on the cover of Elle magazine at age 14.

Bardot once described her childhood as “difficult” and said her father was a strict disciplinarian who would sometimes punish her with a horse whip.

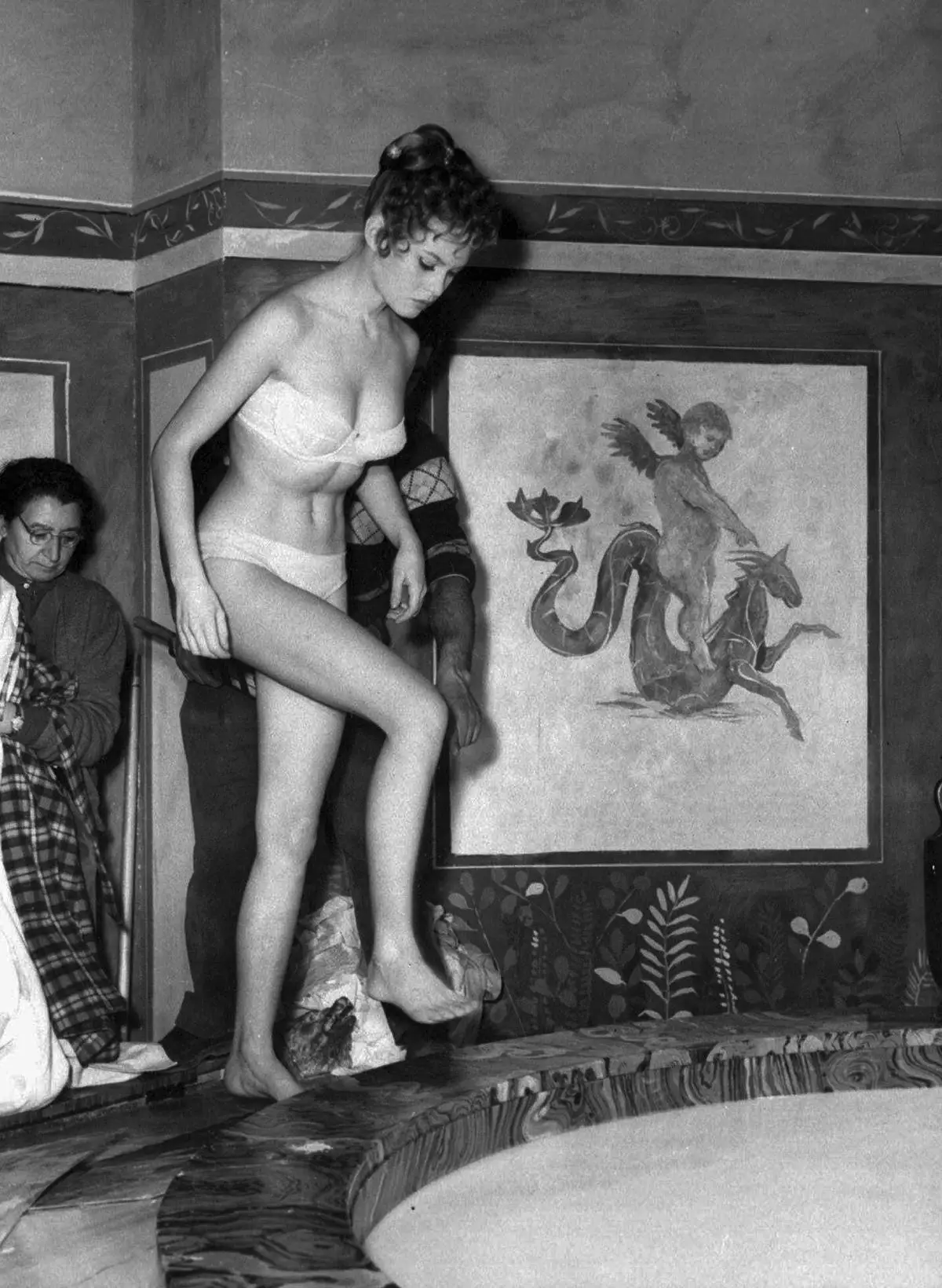

But it was French movie producer Vadim, whom she married in 1952, who saw her potential and wrote “And God Created Woman” to showcase her provocative sensuality, an explosive cocktail of childlike innocence and raw sexuality.

The film, which portrayed Bardot as a bored newlywed who beds her brother-in-law, had a decisive influence on New Wave directors Jean-Luc Godard and Francois Truffaut, and came to embody the hedonism and sexual freedom of the 1960s.

The film was a box-office hit, and it made Bardot a superstar. Her girlish pout, tiny waist and generous bust were often more appreciated than her talent.

“It’s an embarrassment to have acted so badly,” Bardot said of her early films. “I suffered a lot in the beginning. I was really treated like someone less than nothing.”

Bardot’s unabashed, off-screen love affair with co-star Jean-Louis Trintignant further shocked the nation. It eradicated the boundaries between her public and private life and turned her into a hot prize for paparazzi.

Bardot never adjusted to the limelight. She blamed the constant press attention for the suicide attempt that followed 10 months after the birth of her only child, Nicolas. Photographers had broken into her house two weeks before she gave birth to snap a picture of her pregnant.

Nicolas’ father was Jacques Charrier, a French actor whom she married in 1959 but who never felt comfortable in his role as Monsieur Bardot. Bardot soon gave up her son to his father, and later said she had been chronically depressed and unready for the duties of being a mother.

“I was looking for roots then,” she said in an interview. “I had none to offer.”

In her 1996 autobiography “Initiales B.B.,” she likened her pregnancy to “a tumor growing inside me,” and described Charrier as “temperamental and abusive.”

Bardot married her third husband, West German millionaire playboy Gunther Sachs, in 1966, but the relationship again ended in divorce three years later.

Among her films were “A Parisian” (1957); “In Case of Misfortune,” in which she starred in 1958 with screen legend Jean Gabin; “The Truth” (1960); “Private Life” (1962); “A Ravishing Idiot” (1964); “Shalako” (1968); “Women” (1969); “The Bear And The Doll” (1970); “Rum Boulevard” (1971); and “Don Juan” (1973).

With the exception of 1963’s critically acclaimed “Contempt,” directed by Godard, Bardot’s films were rarely complicated by plots. Often they were vehicles to display Bardot in scanty dresses or frolicking nude in the sun.

“It was never a great passion of mine,” she said of filmmaking. “And it can be deadly sometimes. Marilyn (Monroe) perished because of it.”

Bardot retired to her Riviera villa in St. Tropez at the age of 39 in 1973 after “The Woman Grabber.”

She emerged a decade later with a new persona: An animal rights lobbyist, her face was wrinkled and her voice was deep following years of heavy smoking. She abandoned her jet-set life and sold off movie memorabilia and jewelry to create a foundation devoted exclusively to the prevention of animal cruelty.

Her activism knew no borders. She urged South Korea to ban the sale of dog meat and once wrote to U.S. President Bill Clinton asking why the U.S. Navy recaptured two dolphins it had released into the wild.

She attacked centuries-old French and Italian sporting traditions including the Palio, a free-for-all horse race, and campaigned on behalf of wolves, rabbits, kittens and turtle doves.

“It’s true that sometimes I get carried away, but when I see how slowly things move forward ... my distress takes over,” Bardot told the AP when asked about her racial hatred convictions and opposition to Muslim ritual slaughter,

In 1997, several towns removed Bardot-inspired statues of Marianne after the actress voiced anti-immigrant sentiment. Also that year, she received death threats after calling for a ban on the sale of horse meat.

Bardot once said that she identified with the animals that she was trying to save.

“I can understand hunted animals because of the way I was treated,” Bardot said. “What happened to me was inhuman. I was constantly surrounded by the world press.”

Ganley contributed to this story before her retirement. Angela Charlton in Paris contributed to this report.

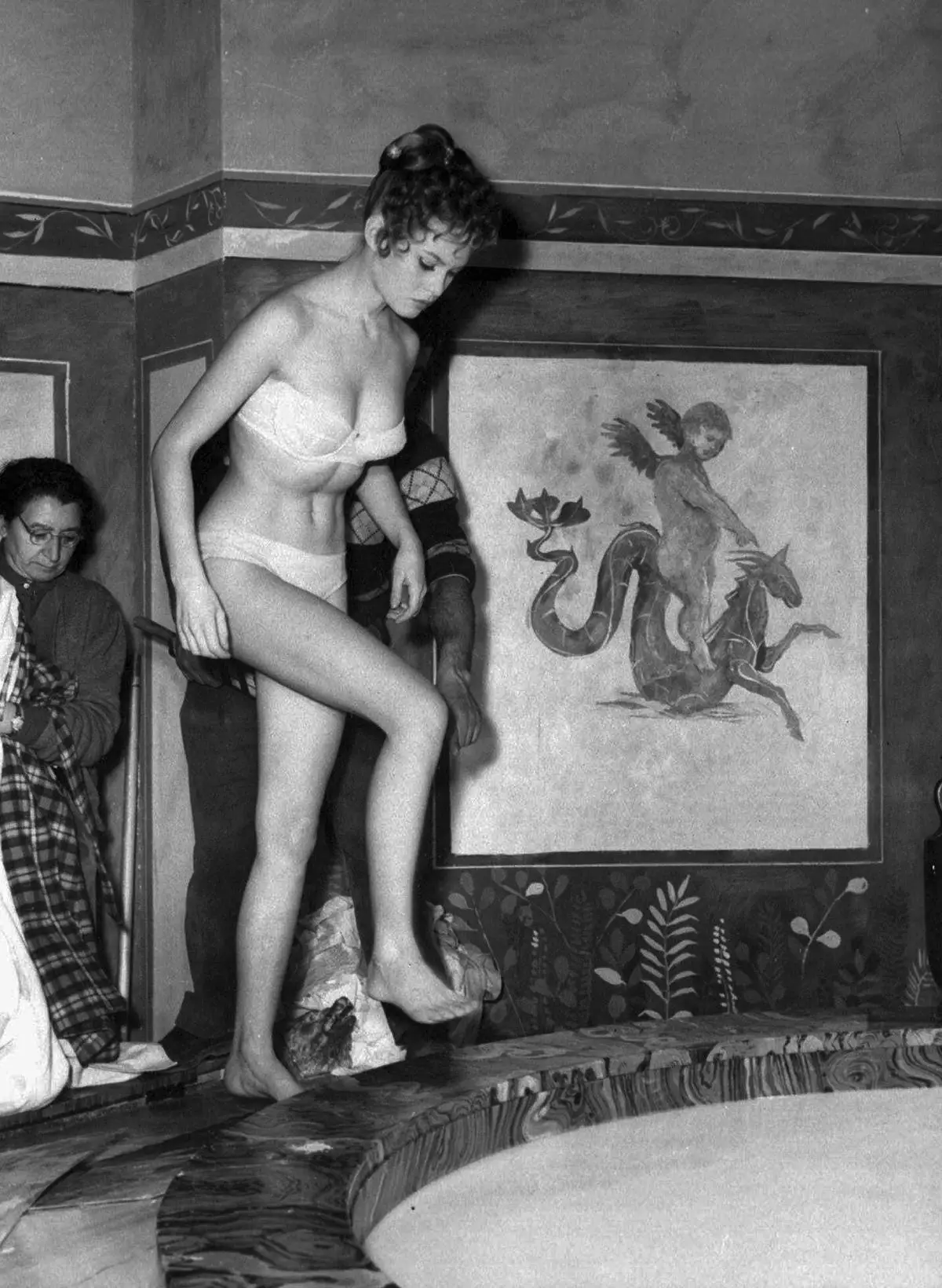

FILE - French actress Brigitte Bardot steps into a milk bath while filming the comedy "Nero's Big Weekend," in Rome March 27, 1956. (AP Photo/File)

FILE - French Actress Brigitte Bardot with a dog in the Gennevilliers, Paris, while supporting the French animal protection society operation, Feb. 10, 1982. (AP Photo/Duclos, File)

FILE - French actress Brigitte Bardot poses in character from the motion picture "Voulez-Vous Danser Avec Moi" (Do you Want to Dance With Me), on Sept. 10, 1959. (AP Photo/File)

FILE - French film legend and animal rights activist Brigitte Bardot looks on prior to a march of various animal rights associations on March 24, 2007 in Paris. (AP Photo/Jacques Brinon, file)

FILE - French actress Brigitte Bardot poses with a huge sombrero she brought back from Mexico, as she arrives at Orly Airport in Paris, France, on May 27, 1965. (AP Photo/File)