MANSFIELD, La. (AP) — The strip search lasted just six minutes, but when it ended, Jarius Brown had a broken nose, fractured eye socket and a badly swollen face.

Never-before-published footage shows why: Two Louisiana sheriff’s deputies pummeled the naked 25-year-old, flinging him around the DeSoto Parish Detention Center laundry room while landing a flurry of 50 punches.

In the aftermath of the 2019 assault, one of the deputies resigned and the other was suspended. Internal records show the sheriff’s office concluded “there was no way of defending” the deputies' actions.

Yet, that’s just what the Louisiana State Police did, an Associated Press investigation has found. After waiting months to analyze the graphic video and more than a year to even interview Brown, the agency cleared the deputies of wrongdoing. The state police ultimately supported the deputies’ claims that Brown had been the “aggressor" in an altercation that took place after he had been arrested on charges of stealing a car.

The case might have ended there had federal prosecutors not eventually gotten involved and come to the opposite conclusion: Brown had been the victim of excessive force.

The graphic footage remained under wraps for six years but emerged this month in Brown’s long-running lawsuit seeking damages for his injuries. Brown, now 32, declined to comment through his attorneys.

Gary Evans, a former DeSoto Parish district attorney, said the case underscores the safety net the Justice Department long provided in smaller communities — a role many advocates fear has been thrown into doubt as the department dials back its civil rights enforcement amid President Donald Trump’s mandate to “unleash” the police.

“This was a great miscarriage of justice at the state level, and it shows the system has broken down and doesn’t protect citizens,” Evans said. “In a community like this, the federal government is the only avenue for anything to get done.”

Brown’s beating was just the latest in a litany of police misconduct cases in DeSoto Parish, a rural swath of piney woods and rolling farmlands south of Shreveport, Louisiana.

A month before Brown was pummeled, another deputy was charged with malfeasance after tackling and repeatedly punching a man walking into a grocery store. He agreed to a permanent ban from law enforcement in exchange for the charges being dismissed. In another case, a DeSoto Parish deputy was charged with third-degree rape after ordering a woman he arrested to perform oral sex on him.

Russell Graham, a state police spokesperson, declined to explain his agency’s conclusion that there “was not sufficient evidence” the deputies in Brown's case committed a crime. He attributed delays in the investigation to the COVID-19 pandemic, which began six months after the beating.

“LSP remains committed to thorough, impartial investigations and working with partners to ensure accountability and uphold public trust,” Graham wrote in an email to AP, adding the agency had “conducted a thorough investigation of this matter when it was presented to them.”

Former deputy Javarrea Pouncy pleaded guilty to using excessive force and was sentenced last year to serve about three years in federal prison. He could not be reached for comment.

The other deputy, DeMarkes Grant, who pleaded guilty to obstructing justice, was released from prison in April after serving a 10-month sentence. Grant told AP he was still “stressed out” and had “lost a lot” as a result of his conviction. He declined to say whether he regretted the beating.

“What has happened has happened,” he said.

Use of force experts questioned the divergent outcomes at the state and federal level, saying Brown never posed a threat and the beating was excessive.

The grainy footage shows a handcuffed Brown calmly walking into the jail’s laundry room before disrobing. The beating begins halfway through the search, after the deputies confront Brown for not squatting as directed so they could fully search him.

Neither deputy sought medical care for Brown after the beating, but the warden recognized the man needed attention and ensured he was taken to the hospital.

“I don’t know how any objective evaluator of this incident could determine this was anything but excessive,” said Charles “Joe” Key, a former Baltimore police lieutenant who typically testifies in defense of police and reviewed the footage at AP’s request.

Andrew Scott, a former police chief of Boca Raton, Florida, said there was nothing on the video that would have justified the beating. He could only surmise the deputies were “delivering retribution.” Any police official who justified the beating after watching the video, Scott added, is “not a competent or truthful expert.”

Within days of the beating, DeSoto Parish Sheriff Jayson Richardson suspended Grant and elicited Pouncy’s resignation. He defended the state police probe in a recent interview, saying federal and state reviews weren’t an “apples to apples” comparison due to differing criminal statutes.

Evans, the former district attorney, said local officials repeatedly thwarted his efforts to obtain the video.

Louisiana State Police ultimately provided the beating video to Evans’ successor, Charles Adams, who closed the investigation in 2021. Regardless of what the video shows, Adams told AP, the state police report would have made a state prosecution “very difficult, if not impossible” because it concluded there wasn’t enough evidence of a crime.

“That report would have been brought out and beat over our head,” Adams said.

The state police report describes Brown as the aggressor and said the man told troopers he was “probably high” when he was attacked but that officers took “appropriate action” against him.

State investigators also concluded the footage supported the deputies’ accounts of the attack. The U.S. Justice Department, however, charged both deputies with falsifying their reports, which Grant admitted were fabricated to create a “false narrative.”

Weeks after the September 2019 beating at the jail, Brown pleaded guilty to ”unauthorized use of a motor vehicle” and was sentenced to 18 months behind bars. State police interviewed Brown in jail in early 2021 and reported he “did not want anything done” about the beating and “was not interested in pursuing the matter criminally or civilly.”

A local judge, Amy McCartney, dismissed the lawsuit Brown filed against the deputies, ruling in 2023 the beating did not constitute a “crime of violence.” An appeals court reversed that decision, and Brown’s lawyers are seeking damages for his injuries and medical expenses.

“Jarius Brown survived a horrific, unprovoked beating,” said Brown’s attorney, Michael Imbroscio, adding he is “entitled to justice.” Brown also is represented by the American Civil Liberties Union of Louisiana, which fought a lengthy legal battle related to the state’s statute of limitations on civil claims stemming from police violence.

Brown’s father, Derek Washington, said the attack sent his son’s already unstable mental capacity “into a more severe case of schizophrenia and anxiety.” Today, Brown is fearful of crowds and closed-in spaces, he said, and “cannot function in society.”

“He always thinks someone is trying to harm him physically,” Washington said. “Right now, my son is just a stranger, and I just want to get some semblance of him back.”

Brook reported from New Orleans.

Contact the AP’s global investigative team at Investigative@ap.org or https://www.ap.org/tips/

In this image from surveillance video provided by the Louisiana State Police, Jarius Brown is restrained by then-Deputy DeMarkes Grant as Sgt. Javarrea Pouncy strikes him in a laundry room of the DeSoto Parish Detention Center in Mansfield, La., on Sept. 27, 2019. (Louisiana State Police via AP)

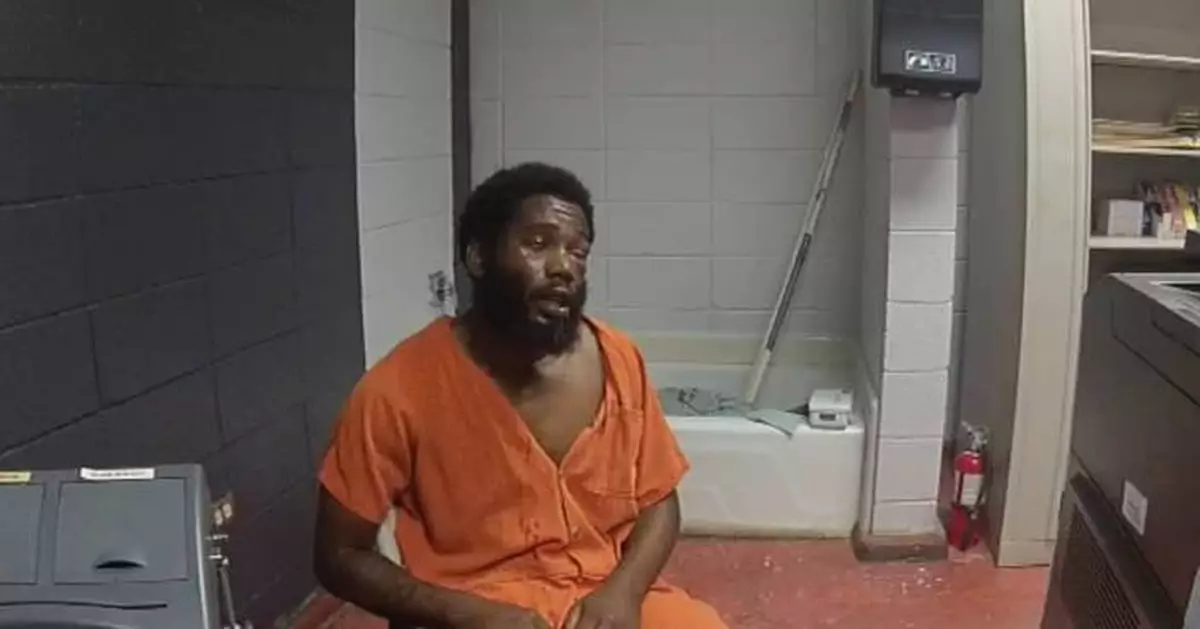

In this image from body camera video from the DeSoto Parish Sheriff's Office, Jarius Brown is interviewed following a jailhouse beating that left him with a bruised face, fractured eye socket and broken nose at the DeSoto Parish Detention Center in Mansfield, La., on Sept. 27, 2019. (DeSoto Parish Sheriff's Office via AP)