LOS ANGELES (AP) — Iris Delgado started a running club in her largely Latino, Los Angeles suburb two years ago to connect runners and advocate for safety measures like crosswalks and designated bike lanes.

Now, with the Trump administration's immigration raids rocking Huntington Park, the group’s motto of keeping each other safe has taken on even greater meaning.

Click to Gallery

Members of the Huntington Park Run Club jog through a neighborhood in Huntington Park, Calif., Sept. 24, 2025. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Joshua Perez, right, and Jayden Chamale, members of the Huntington Park Run Club, run through a neighborhood in Huntington Park, Calif., Sept. 17, 2025. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Rosa Abundiz, center, is greeted by fellow members of the Huntington Park Run Club after finishing the course in Huntington Park, Calif., Sept. 24, 2025. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

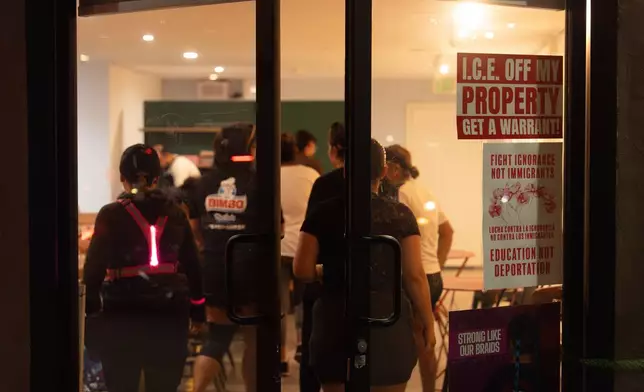

Members of the Huntington Park Run Club enter a pop-up coffee shop set up inside an art gallery in Huntington Park, Calif., Sept. 24, 2025, as signs on the door call for immigrant rights. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Iris Delgado, center, founder of the Huntington Park Run Club, leads a huddle after their run in Huntington Park, Calif., Sept. 24, 2025. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

The Huntington Park Run Club's Instagram carries posts warning of federal immigration agent sightings. A bike marshal accompanies every meet-up, zipping past the runners on his electric bike to ensure everyone is accounted for and feeling good. Since the raids ramped up this summer, Delgado also brings flyers and cards to each run informing people and local businesses of their rights.

Less than a mile north of her route is a Home Depot whose parking lot has been hit multiple times by immigration raids, causing the next door high school to go into lockdown during its graduation ceremony in June. A few blocks south is the home where a woman and her two children were sleeping when federal agents used explosives that blasted the door off and shattered windows. They were looking for a man who was wanted for allegedly ramming his car into a U.S. Customs and Border Patrol vehicle during a protest. The case has since been dismissed.

Amidst it all, the Huntington Park Run Club runs on, trying to protect and reclaim the streets the runners call home.

Evelyn Romo, 25, who joined the club after she returned home from college, said just going out to run now makes a statement in the community.

“Continuing to take up space even in the form of running in these streets is a form of protest, is a form of resistance,” she said.

The club has never canceled a run. It’s important to maintain a space for people to come and decompress, and feel safe, Delgado said.

Delgado runs twice a week with her group. On a recent Wednesday, she led around 30 runners in warm-up stretches, and then they were off, streaming ahead of and behind her, their feet striking the pavement in quick succession. The group’s members range from as young as 11 to people in their 60s and 70s.

Delgado said her club’s members reflect the larger community and that they do not share the immigration status of participants.

The Trump administration’s focus on arresting people suspected of living in the country illegally has transformed life for tens of thousands of people in Los Angeles County, the nation’s most populous county. About a third of the county’s 10 million residents are foreign-born, and an untold number of people are now trying to live without being seen.

Huntington Park, along with several other cities in the region, canceled its Fourth of July celebration and summer movie nights as families stayed home due to safety concerns.

U.S. citizens and other legal residents have been swept up in raids. The Supreme Court recently lifted temporary restrictions from a judge who found that roving patrols were conducting indiscriminate stops in and around LA. The order had barred immigration agents from stopping people solely based on their race, language, job or location.

Marco Padilla, 18, joined the club a week after it began two years ago.

Padilla, who was born and raised in Huntington Park, said everyone in the community has felt the effects of the raids, regardless of their immigration status. Some of his friends’ parents have been worried about letting them hang out in public places like the park, and others have told him it's too dangerous to be running by immigration “hot spots.”

He recalled the morning of his high school senior breakfast, when he and his friends heard yelling and screaming as armed immigration officers ran past just beyond the school's gates.

“Some people have chosen to be hidden ... but ironically for our group, we have actually decided to do the opposite,” he said.

The club has held several fundraisers for a community fund, raising about $8,000 to date to support day laborers at Home Depot stores, which have long been informal job-seeking hubs for workers in the country both legally and illegally. Now the locations have become a prime target for immigration agents.

Being part of the community, the runners have a responsibility to alert people to the raids and document them with their phones, Delgado said. The club has hosted trainings on how to do that safely and informs runners who to call if they see something. Some club members said they’ve witnessed raids while running on their own, and quickly let Delgado know or messaged their group chat.

“Our main community value is to keep each other safe and look out for each other," Delgado said. “That agreement is part of our culture at this point.”

Members of the Huntington Park Run Club jog through a neighborhood in Huntington Park, Calif., Sept. 24, 2025. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Joshua Perez, right, and Jayden Chamale, members of the Huntington Park Run Club, run through a neighborhood in Huntington Park, Calif., Sept. 17, 2025. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Rosa Abundiz, center, is greeted by fellow members of the Huntington Park Run Club after finishing the course in Huntington Park, Calif., Sept. 24, 2025. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Members of the Huntington Park Run Club enter a pop-up coffee shop set up inside an art gallery in Huntington Park, Calif., Sept. 24, 2025, as signs on the door call for immigrant rights. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Iris Delgado, center, founder of the Huntington Park Run Club, leads a huddle after their run in Huntington Park, Calif., Sept. 24, 2025. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

WASHINGTON (AP) — Michael Ben'Ary was driving one of his children to soccer practice on an October evening last year when he paused at a red light to check his work phone. He was in the middle of a counterterrorism prosecution so important that President Donald Trump highlighted it in his State of the Union address.

Ben'Ary said he was shocked to see his phone had been disabled. He found the explanation later in his personal email account, a letter informing him he had been fired.

A veteran prosecutor, Ben'Ary handled high-profile cases over two decades at the Justice Department, including the murder of a Drug Enforcement Administration agent and a suicide bomb plot targeting the U.S. Capitol. Most recently he was leading the case arising from a deadly attack on American service members in Afghanistan.

Yet the same credentials that enhanced Ben'Ary's résumé spelled the undoing of his government career.

His termination without explanation came hours after right-wing commentator Julie Kelly told hundreds of thousands of online followers that he had previously served as a senior counsel to Lisa Monaco, the No. 2 Justice Department official in President Joe Biden's Democratic administration. Kelly also suggested Ben'Ary was part of the “internal resistance” to prosecuting former FBI Director James Comey, even though Ben’Ary was never involved in the case.

As Attorney General Pam Bondi approaches her first year on the job, the firings of attorneys like Ben’Ary have defined her turbulent tenure. The terminations and a larger voluntary exodus of lawyers have erased centuries of combined experience and left the department with fewer career employees to act as a bulwark for the rule of law at a time when Trump, a Republican, is testing the limits of executive power by demanding prosecutions of his political enemies.

Interviews by The Associated Press of more than a half-dozen fired employees offer a snapshot of the toll throughout the department. The departures include lawyers who prosecuted violent attacks on police at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, environmental, civil rights and ethics enforcers, counterterrorism prosecutors, immigration judges and attorneys who defend administration policies. They continued this week, when several prosecutors in Minnesota moved to resign amid turmoil over an investigation into the shooting of a woman by an Immigration and Customs Enforcement officer.

“To lose people at that career level, people who otherwise intended to stay and now are either being discharged or themselves are walking away, is immensely damaging to the public interest,” said Stuart Gerson, a senior official in the George H.W. Bush administration and acting attorney general early in Bill Clinton's administration. “We’re losing really capable people, people who have never viewed themselves as political and attempted to do the right thing.”

Justice Connection, a network of department alumni, estimates that more than 230 lawyers, agents and other employees from across the department were fired last year — apparently because of their work on cases they were assigned, past criticism of Trump or seemingly no reason. More than 6,400 employees are estimated to have left a department that at the end of 2025 had roughly 108,000, the group says.

The Justice Department says it has hired thousands of career attorneys over the last year. The Trump administration has characterized some of the fired and departed workers as out of step with its agenda.

Ben'Ary left with unfinished business, including the prosecution stemming from the Kabul airport bombing and the national security unit he led at the U.S. attorney's office for the Eastern District of Virginia.

Left to pack his belongings, he posted a typed note near his door that functioned as a distress call, reminding colleagues they had sworn an oath to follow the facts “without fear or favor” and “unhindered by political interference.”

But, he warned, “In recent months, the political leadership of the Department have violated these principles, jeopardizing our national security and making Americans less safe.”

Since its founding in 1870, the Justice Department has occupied elevated status in American democracy, sustained through transitions of power by reliance on facts, evidence and law.

To be sure, there has always been a political component to the department, with lawyers appointed by the president.

But even during turbulent times, when attorneys general have been pushed out by presidents or resigned rather than accede to White House demands — as in the Watergate-era “Saturday Night Massacre" — the department's rank-and-file have generally been insulated thanks to long-recognized civil service protections.

“This is completely unprecedented in both its scale and scope and underlying motivation,” said Peter Keisler, a senior official in the George W. Bush Justice Department.

In his first term, Trump pushed out one attorney general and accepted another's resignation but the workforce remained largely intact. He returned to office seething over Biden-era prosecutions of him, vowing retribution.

The firings began even before Bondi arrived last February. Prosecutors on special counsel Jack Smith's team that investigated Trump were terminated days after the inauguration, followed by prosecutors hired on temporary assignments for cases resulting from the 2021 Capitol insurrection.

"The people working on these cases were not political agents of any kind,” said Aliya Khalidi, a Jan. 6 prosecutor who was fired. “It’s all people who just care about the rule of law.”

The firings have continued, at times surgical, at times random — almost always without explanation.

Adam Schleifer, a Los Angeles prosecutor targeted in a social media post by far-right activist Laura Loomer over past critical comments of Trump, was fired in March. The Justice Department the following month fired attorney Erez Reuveni, who conceded in court that Salvadoran national Kilmar Abrego Garcia was mistakenly deported. Reuveni later accused the department of trying to mislead judges to execute deportations. Department officials deny the assertion.

Two weeks after Maurene Comey completed a sex trafficking trial against Sean “Diddy” Combs, the New York prosecutor was fired, also without explanation. Like Ben'Ary, she penned a pointed farewell, telling colleagues that “fear is the tool of a tyrant.” Her father — former FBI Director James Comey, a frequent Trump target — uttered those same words after being indicted in September in a case that has been dismissed.

Among the most affected sections is the storied Civil Rights Division. A recent open letter of protest was signed by over 200 employees who left in 2025, with several supervisors recently giving notice of plans to depart. The Public Integrity Section, which prosecutes sensitive public corruption cases, has also been hollowed out by resignations.

The Justice Department has disputed the accounts of some of those who have been fired or quit and has defended the termination of those who investigated Trump as “consistent with the mission of ending the weaponization of government.”

“This is the most efficient Department of Justice in American history, and our attorneys will continue to deliver measurable results for the American people,” the department said in a statement. More than 3,400 career attorneys have been hired since Trump took office, the department says.

The departures have caused backlogs and staff shortages, with senior leaders soliciting job applications. It has affected the department’s daily business as well as efforts to fulfill Trump’s desires to prosecute political opponents.

Desperate for lawyers willing to file criminal cases against Comey and New York Attorney General Letitia James, the administration in September forced out the veteran U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia, replacing him with Lindsey Halligan, a White House aide with no experience as a federal prosecutor.

Halligan secured the indictments but the win was short-lived.

One judge later identified grave missteps in how Halligan presented the Comey case to a grand jury. Another dismissed both prosecutions outright, calling Halligan's appointment unlawful.

Smith, the special counsel who investigated Trump but left before he could be fired, has himself lamented the losses. “These are not partisans,” he recently told lawmakers.

“They just want to do good work,” he added, “and I think when you lose that culture, you lose a lot.”

Khalidi joined the department in 2023 in a group of new prosecutors hired to help with the hundreds of cases stemming from the Capitol riot.

Upon Trump's return to the White House, she watched cases she prosecuted get dismantled by Trump’s sweeping clemency for all 1,500 defendants charged in the riot, including those who attacked police.

Less than two weeks later, a Justice Department demand for the names of FBI agents involved in Jan. 6 investigations triggered rumors of potential mass firings. Worried about the agents she worked with, Khalidi spent the day checking in on them. But as she started preparing dinner one Friday evening, she received an email suggesting she had lost her own job.

Attached was a memo from then-Acting Deputy Attorney General Emil Bove ordering the firings of prosecutors like Khalidi who'd been hired for temporary assignments but were moved into permanent roles after Trump’s win, a maneuver Bove called “subversive personnel actions by the previous administration.” Neither the email nor memo identified the fired prosecutors, leaving them to guess.

Khalidi grabbed a suitcase to collect family photos and other personal items she kept at work and rushed to the office, retreating with fellow shocked prosecutors to a bar where they received termination emails.

The group of 15 fired attorneys later assembled to surrender their computers and phones, entering the same room where they gathered on their first day in 2023.

“For a lot of us, our dream was to be federal prosecutors,” Khalidi said. “And so we had happy memories of that room, of being excited on our first day. So it was just kind of surreal to be back there turning in our stuff.”

The news came for Anam Petit, an immigration judge, during a break between hearings.

Appointed during the Biden administration, she said she felt uneasy when Trump won but also figured her position would probably be safe because immigration judges bear responsibility for issuing removal orders for those in the country illegally, a core presidential priority.

Petit arrived on Sept. 5 bracing for bad news because it was the Friday of the pay period before her two-year work anniversary, when her temporary appointment was poised to become permanent. Though she said she had received strong performance reviews and had already exceeded her case completion goal for the year, she had grown anxious as colleagues were fired amid an administration push to accelerate deportations.

She was in the courtroom between hearings when she learned via email she'd been fired. She left to text her husband, then returned to work.

“I just put my phone back in my pocket and I went into the courtroom to deliver my decision, with a very shaky voice and shaky hands, trying to center myself back to that decision to so that I could relay it,” Petit said.

Joseph Tirrell was concerned about job security as far back as last fall. As the department's chief ethics officer, he had affirmed that Smith, the special counsel, was entitled to a law firm's free legal services, a decision he sensed might rile incoming leadership.

But he remained in the position and over the ensuing months counseled Bondi's staff on the propriety of accepting various gifts, including a cigar box from mixed martial arts fighter Conor McGregor.

He was fired in July, just before a FIFA Club World Cup Final in New Jersey that Tirrell had said Bondi could not ethically accept a free invitation to. He was not terribly surprised, he says, when it was later reported that Bondi attended in Trump's box. The Justice Department said in a statement that none of Tirrell's advice “was ever overruled” and that "the Attorney General obtained ethics approval to attend this event in her official capacity as a member of the FIFA Task Force.”

“There’s a great deal of fear there just because I was fired and just because so many others were summarily fired,” Tirrell said. “Are you going to get fired because you provided ethics advice? Are you going to get fired because you have a pride flag on your desk?”

Trump was touting his administration's commitment to counterterrorism during his State of the Union address last March when he announced a success: the capture of an ISIS-K militant charged in a Kabul airport bombing that killed 13 American servicemembers during the 2021 withdrawal from Afghanistan.

Mohammad Sharifullah arrived the following day in the U.S., encountering Ben’Ary in an Alexandria, Virginia, courtroom.

Ben'Ary spent the next several months working on the case, but on Oct. 1, he was fired. It was the apparent result, he told colleagues, of a social media post he said contained “false information" — a reference to the one from Julie Kelly.

The termination was so abrupt, he couldn’t tell his colleagues where he had saved important filings and notes. Another prosecutor listed on the case, Comey's son-in-law, Troy Edwards, had resigned days earlier upon Comey’s indictment. Once set for trial last month, the case has been postponed.

In his farewell note, he observed that he was not alone, that in “just a few short months” career employees like himself had been removed from U.S. attorneys offices, the FBI “and other critical parts of DOJ."

“While I am no longer your colleague, I ask that each of you continue to do the right thing, in the right way, for the right reasons,” Ben'Ary wrote. “Follow the facts and the law. Stand up for what we all believe in — our Constitution and the rule of law. Our country depends on you.”

Anam Petit, a former Justice Department employee, poses for a portrait in the Robert and Arlene Kogod Courtyard at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, Friday, Jan. 9, 2026. (AP Photo/Moriah Ratner)

Anam Petit, a former Justice Department employee, poses for a portrait in the Robert and Arlene Kogod Courtyard at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, Friday, Jan. 9, 2026. (AP Photo/Moriah Ratner)

Anam Petit, a former Justice Department employee, poses for a portrait in the Robert and Arlene Kogod Courtyard at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, Friday, Jan. 9, 2026. (AP Photo/Moriah Ratner)

Attorney General Pam Bondi arrives before President Donald Trump speaks during an event to honor the 2025 Stanley Cup Champion Florida Panthers in the East Room of the White House, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026, in Washington. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

Anam Petit, a former Justice Department employee, poses for a portrait in the Robert and Arlene Kogod Courtyard at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, Friday, Jan. 9, 2026. (AP Photo/Moriah Ratner)