BEIRUT (AP) — Syria is holding parliamentary elections on Sunday for the first time since the fall of the country’s longtime autocratic leader, Bashar Assad, who was unseated in a rebel offensive in December.

Under the 50-year rule of the Assad dynasty, Syria held regular elections in which all Syrian citizens could vote. But in practice, the Assad-led Baath Party always dominated the parliament, and the votes were widely regarded as sham elections.

Outside election analysts said the only truly competitive part of the process came before election day — with the internal primary system in the Baath Party, when party members jockeyed for positions on the list.

The elections to be held on Sunday, however, will not be a fully democratic process either. Rather, most of the People’s Assembly seats will be voted on by electoral colleges in each district, while one-third of the seats will be directly appointed by interim President Ahmad al-Sharaa.

Despite not being a popular vote, the election results will likely be taken as a barometer of how serious the interim authorities are about inclusivity, particularly of women and minorities.

Here’s a breakdown of how the elections will work and what to watch.

The People’s Assembly has 210 seats, of which two-thirds will be elected on Sunday and one-third appointed. The elected seats are voted upon by electoral colleges in districts throughout the country, with the number of seats for each district distributed by population.

In theory, a total of 7,000 electoral college members in 60 districts — chosen from a pool of applicants in each district by committees appointed for the purpose — should vote for 140 seats.

However, the elections in Sweida province and in areas of the northeast controlled by the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces have been indefinitely postponed due to tensions between the local authorities in those areas and the central government in Damascus, meaning that those seats will remain empty.

In practice, therefore, around 6,000 electoral college members will vote in 50 districts for about 120 seats.

The largest district is the one containing the city of Aleppo, where 700 electoral college members will vote to fill 14 seats, followed by the city of Damascus, with 500 members voting for 10 seats.

All candidates come from the membership of the electoral colleges.

Following Assad’s ouster, the interim authorities dissolved all existing political parties, most of which were closely affiliated with the Assad government, and have not yet set up a system for new parties to register, so all candidates are running as individuals.

The interim authorities have said that it would be impossible to create an accurate voter registry and conduct a popular vote at this stage, given that millions of Syrians were internally or externally displaced by the country's nearly 14-year civil war and many have lost personal documents.

This parliament will have a 30-month term, during which the government is supposed to prepare the ground for a popular vote in the next elections.

The lack of a popular vote has drawn criticism of being undemocratic, but some analysts say the government's reasons are legitimate.

“We don’t even know how many Syrians are in Syria today,” because of the large number of displaced people, said Benjamin Feve, a senior research analyst at the Syria-focused Karam Shaar Advisory consulting firm.

“It would be really difficult to draw electoral lists today in Syria,” or to arrange the logistics for Syrians in the diaspora to vote in their countries of residence, he said.

Haid Haid, a senior research fellow at the Arab Reform Initiative and the Chatham House think tank said that the more concerning issue was the lack of clear criteria under which electors were selected.

“Especially when it comes to choosing the subcommittees and the electoral colleges, there is no oversight, and the whole process is sort of potentially vulnerable to manipulation,” he said.

There have been widespread objections after electoral authorities “removed names from the initial lists that were published, and they did not provide detailed information as to why those names were removed,” he said.

There is no set quota for representation of women and religious or ethnic minorities in the parliament.

Women were required to make up 20% of electoral college members, but that did not guarantee that they would make up a comparable percentage of candidates or of those elected.

State-run news agency SANA, citing the head of the national elections committee, Mohammed Taha al-Ahmad, reported that women made up 14% of the 1,578 candidates who made it to the final lists. In some districts, women make up 30 or 40% of all candidates, while in others, there are no female candidates.

Meanwhile, the exclusion of the Druze-majority Sweida province and Kurdish-controlled areas in the northeast as well as the lack of set quotas for minorities has raised questions about representation of communities that are not part of the Sunni Arab national majority.

The issue is particularly sensitive after outbreaks of sectarian violence in recent months in which hundreds of civilians from the Alawite and Druze minorities were killed, many of them by government-affiliated fighters.

Feve noted that electoral districts had been drawn in such a way as to create minority-majority districts.

“What the government could have done if it wanted to limit the number of minorities, it could have merged these districts or these localities with majority Sunni Muslim districts,” he said. “They could have basically drowned the minorities which is what they didn’t do.”

Officials have also pointed to the one-third of parliament directly appointed by al-Sharaa as a mechanism to “ensure improvement in the inclusivity of the legislative body,” Haid said. The idea is that if few women or minorities are elected by the electoral colleges, the president would include a higher percentage in his picks.

The lack of representation of Sweida and the northeast remains problematic, Haid said — even if al-Sharaa appoints legislators from those areas.

“The bottom line is that regardless of how many people will be appointed from those areas, the dispute between the de facto authorities and Damascus over their participation in the political process will remain a major issue,” he said.

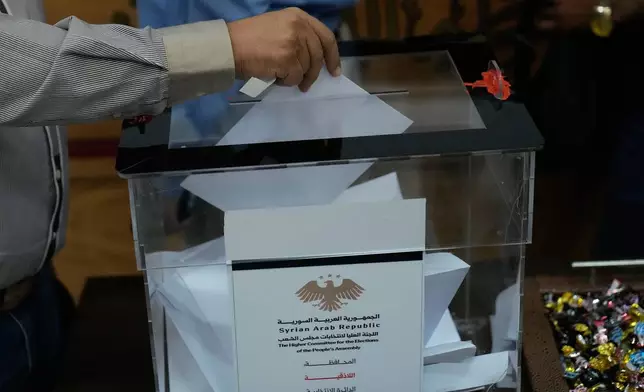

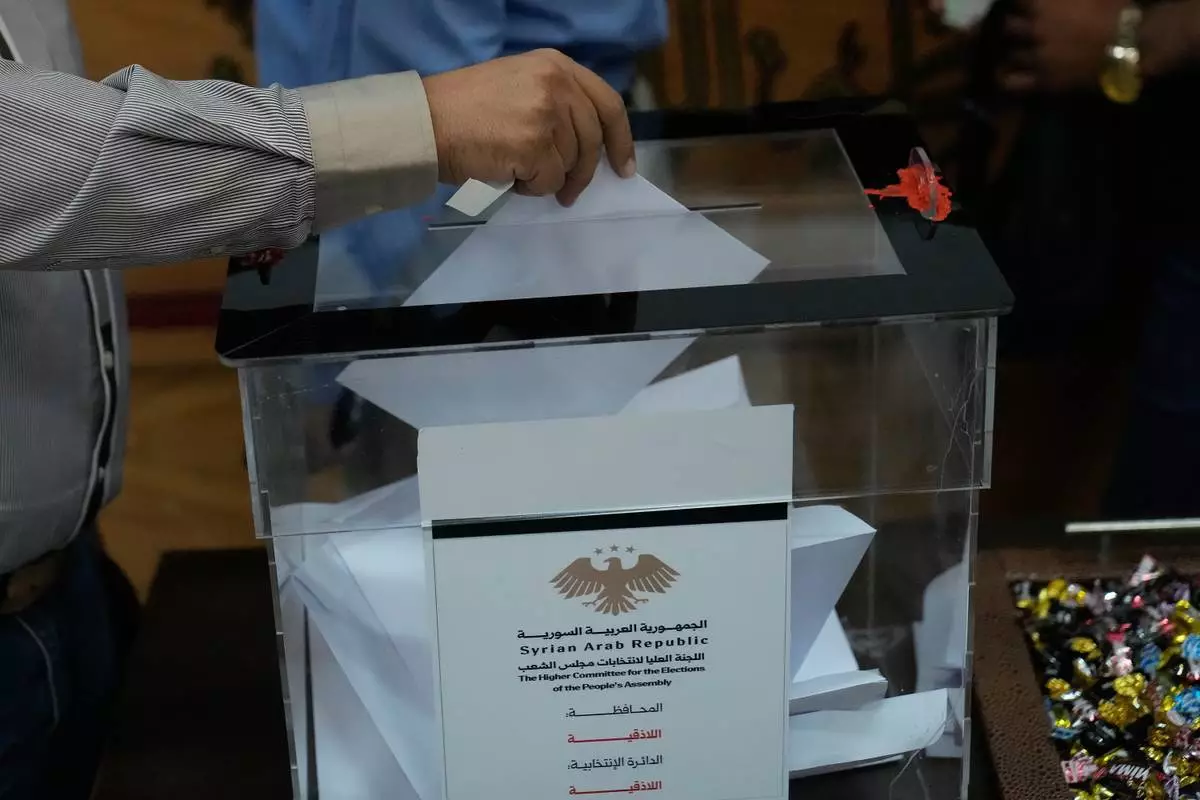

A Syrian electoral college member casts his vote during the parliamentary elections at Latakia's Governor ballot station, in the coastal city of Latakia, Syria, Sunday, Oct. 5, 2025. (AP Photo/Hussein Malla)

A Syrian electoral college member casts his vote during the parliamentary elections at Latakia's Governor ballot station, in the coastal city of Latakia, Syria, Sunday, Oct. 5, 2025. (AP Photo/Hussein Malla)

A Syrian policeman stands guard at Latakia's Governor building where the voting for a parliamentary election will take place, in the coastal city of Latakia, Syria, Sunday, Oct. 5, 2025. (AP Photo/Hussein Malla)

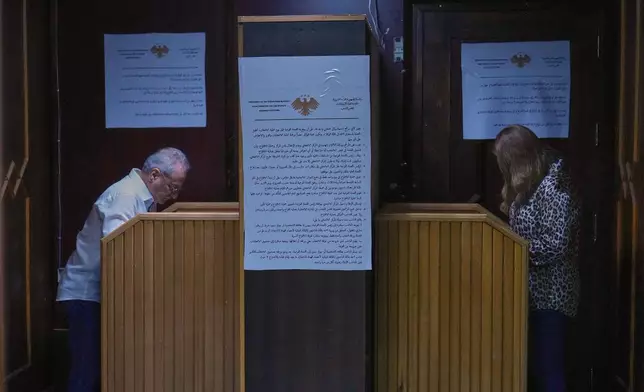

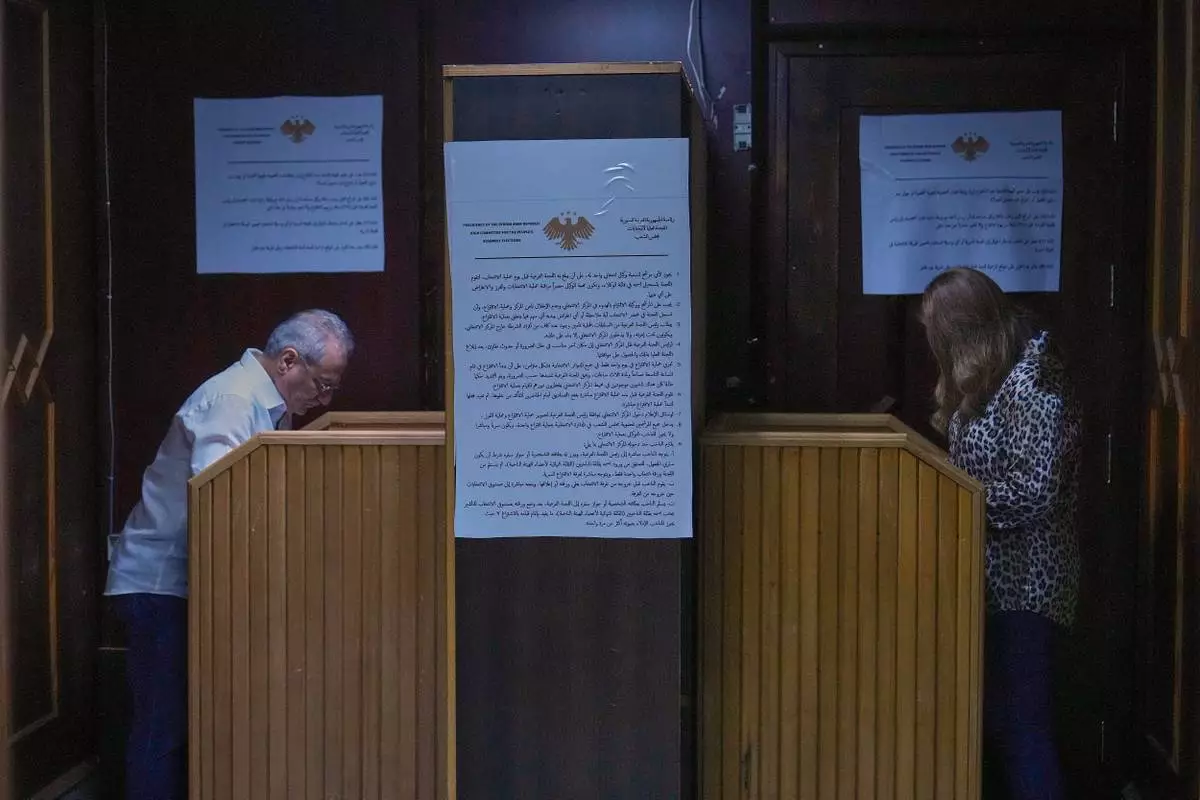

A Syrian electoral college member fills his ballot at the secret room during a parliamentary election at Latakia's Governor ballot station, in the coastal city of Latakia, Syria, Sunday, Oct. 5, 2025. (AP Photo/Hussein Malla)

A Syrian electoral college member casts his vote during a parliamentary election at Latakia's Governor ballot station, in the coastal city of Latakia, Syria, Sunday, Oct. 5, 2025. (AP Photo/Hussein Malla)

Syrian electoral college members line up to cast their ballots in a parliamentary election at a polling station in Damascus, Syria, Sunday, Oct. 5, 2025. (AP Photo/Omar Sanadiki)

A poster shows Syrian-American Jew Henry Hamra, a candidate for the Syrian Parliamentary elections, in the Jewish neighborhood of old Damascus, Syria Friday, Oct. 3, 2025. (AP Photo/Hussein Malla)

Residents watch a celebration below marking the opening of a new shop in the Damascus suburb of Daraya, Syria, Saturday, Oct. 4, 2025, ahead of a parliamentary election set to take place Sunday. (AP Photo/Omar Sanadiki)

A man waits for customers at a stall beside war-damaged buildings ahead of a parliamentary election set to take place Sunday, in the Damascus suburb of Daraya, Syria, Saturday, Oct. 4, 2025. (AP Photo/Omar Sanadiki)

FILE - In this photo released by the Syrian official news agency SANA, Syria's interim President Ahmad al-Sharaa receives the final version of the provisional electoral system for the People's Assembly, in Damascus, Syria, Sunday, July 27, 2025. (SANA via AP, file)