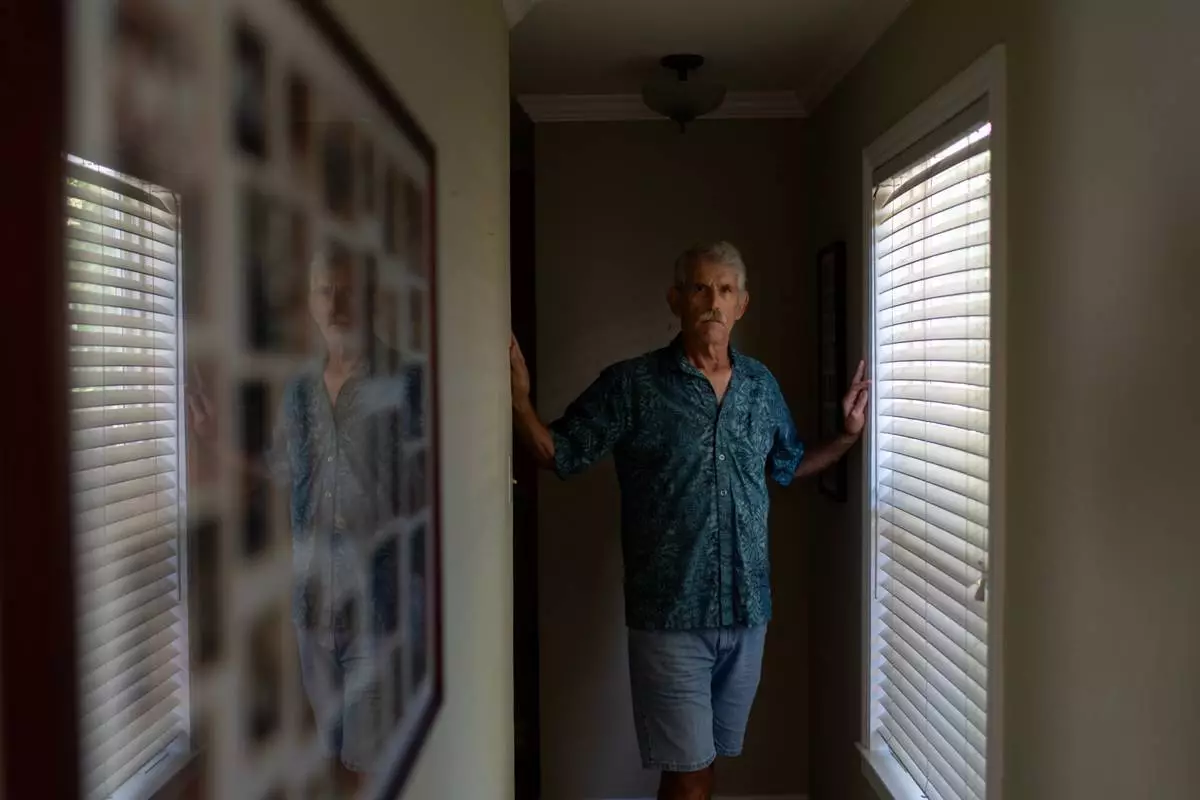

“My year of unraveling” is how a despairing Christy Morrill described nightmarish months when his immune system hijacked his brain.

What’s called autoimmune encephalitis attacks the organ that makes us “us,” and it can appear out of the blue.

Morrill went for a bike ride with friends along the California coast, stopping for lunch, and they noticed nothing wrong. Neither did Morrill until his wife asked how it went — and he'd forgotten. Morrill would get worse before he got better. “Unhinged” and “fighting to see light,” he wrote as delusions set in and holes in his memory grew.

Of all the ways our immune system can run amok and damage the body instead of protecting it, autoimmune encephalitis is one of the most unfathomable. Seemingly healthy people abruptly spiral with confusion, memory loss, seizures, even psychosis.

But doctors are getting better at identifying it, thanks to discoveries of a growing list of the rogue antibodies responsible that, if found in blood and spinal fluid, aid diagnosis. Every year new culprit antibodies are being uncovered, said Dr. Sam Horng, a neurologist at Mount Sinai Health System in New York who has cared for patients with multiple forms of this mysterious disease.

And while treatment today involves general ways to fight the inflammation, two major clinical trials are underway aiming for more targeted therapy.

Still, it's tricky. Symptoms can be mistaken for psychiatric or other neurologic disorders, delaying proper treatment.

“When someone’s having new changes in their mental status, they’re worsening and if there’s sort of like a bizarre quality to it, that’s something that kind of tips our suspicion,” Horng said. “It’s important not to miss a treatable condition.”

With early diagnosis and care, some patients fully recover. Others like Morrill recover normal daily functioning but grapple with some lasting damage — in his case, lost decades of “autobiographical” memories. This 72-year-old literature major can still spout facts and figures learned long ago, and he makes new memories every day. But even family photos can’t help him recall pivotal moments in his own life.

“I remember ‘Ulysses’ is published in Paris in 1922 at Sylvia Beach’s bookstore. Why do I remember that, which is of no use to me anymore, and yet I can’t remember my son’s wedding?” Morrill wonders.

Encephalitis means the brain is inflamed and symptoms can vary from mild to life-threatening. Infections are a common cause, typically requiring treatment of the underlying virus or bacteria. But when that's ruled out, an autoimmune cause has to be considered, Horng said, especially when symptoms arise suddenly.

The umbrella term autoimmune encephalitis covers a group of diseases with weird-sounding names based on the antibody fueling it, such as anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis.

While they're not new diseases, that one got a name in 2007 when Dr. Josep Dalmau, then at the University of Pennsylvania, discovered the first culprit antibody, sparking a hunt for more.

That anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis tends to strike younger women and, one of the bizarre factors, it’s sometimes triggered by an ovarian “dermoid” cyst.

How? That type of cyst has similarities to some brain tissue, Horng explained. The immune system can develop antibodies recognizing certain proteins from the growth. If those antibodies get into the brain, they can mistakenly target NMDA receptors on healthy brain cells, sparking personality and behavior changes that can include hallucinations.

Different antibodies create different problems depending if they mostly hit memory and mood areas in the brain, or sensory and movement regions.

Altogether, “facets of personhood seem to be impaired," Horng said.

Therapies include filtering harmful antibodies out of patients' blood, infusing healthy ones, and high-dose steroids to calm inflammation.

Those cyst-related antibodies stealthily attacked Kiara Alexander in Charlotte, North Carolina, who’d never heard of the brain illness. She’d brushed off some oddities — a little forgetfulness, zoning out a few minutes — until she found herself in an ambulance because of a seizure.

Maybe dehydration, the first hospital concluded. At a second hospital after a second seizure, a doctor recognized the possible signs, ordering a spinal tap that found the culprit antibodies.

As Alexander's treatment began, other symptoms ramped up. She has little clear memory of the monthlong hospital stay: “They said I would just wake up screaming. What I could remember, it was like a nightmare, like the devil trying to catch me.”

Later Alexander would ask about her 9-year-old daughter and when she could go home — only to forget the answer and ask again.

Alexander feels lucky she was diagnosed quickly, and she got the ovarian cyst removed. But it took over a year to fully recover and return to work full time.

In San Carlos, California, in early 2020, it was taking months to determine what caused Morrill's sudden memory problem. He remembered facts and spoke eloquently but was losing recall of personal events, a weird combination that prompted Dr. Michael Cohen, a neurologist at Sutter Health, to send him for more specialized testing.

“It’s very unusual, I mean extremely unusual, to just complain of a problem with autobiographical memory,” Cohen said. “One has to think about unusual disorders.”

Meanwhile Morrill’s wife, Karen, thought she’d detected subtle seizures — and one finally happened in front of another doctor, helping spur a spinal tap and diagnosis of LGI1-antibody encephalitis.

It’s a type most common in men over age 50. Those rogue antibodies disrupt how neurons signal each other, and MRI scans showed they’d targeted a key memory center.

By then Morrill, who’d spent retirement guiding kayak tours, could no longer safely get on the water. He’d quit reading and as his treatments changed, he’d get agitated with scary delusions.

“I lost total mental capacity and fell apart,” Morrill describes it.

He used haiku to make sense of the incomprehensible, and months into treatment finally wondered if the “meds coursing through me” really were “dousing the fire. Rays of hope?”

The nonprofit Autoimmune Encephalitis Alliance lists about two dozen antibodies — and counting — known to play a role in these brain illnesses so far.

Clinical trials, offered at major medical centers around the country, are testing two drugs now used for other autoimmune diseases to see if tamping down antibody production can ease encephalitis.

More awareness of these rare diseases is critical, said North Carolina's Alexander, who sought out fellow patients. “That's a terrible feeling, feeling like you're alone.”

As for Morrill, five years later he still grieves decades of lost memories: family gatherings, a year spent studying in Scotland, the travel with his wife.

But he’s making new memories with grandkids, is back outdoors — and leads an AE Alliance support group, using his haiku to illustrate the journey from his “unraveling” to “the present is what I have, daybreaks and sunsets” to, finally, “I can sustain hope.”

“I’m reentering some real time of fun, joy,” Morrill said. “I wasn’t shooting for that. I just wanted to be alive.”

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Department of Science Education and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Kiara Alexander, left, who was hospitalized with autoimmune encephalitis, leaves a grocery store with her daughter Kennedi, Friday, Oct. 10, 2025, in Charlotte, N.C. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

Kiara Alexander, who was hospitalized with autoimmune encephalitis, poses for a photo at her home, Friday, Oct. 10, 2025, in Charlotte, N.C. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

Christy Morrill, 72, who lost decades of memories to autoimmune encephalitis, looks over a photo album of his son's wedding, at his home, Tuesday, Aug. 19, 2025, in San Carlos, Calif. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

Christy Morrill, 72, left, who lost decades of memories to autoimmune encephalitis, looks over family photo albums with, from left, his wife Karen, daughter Caitlin and grandson Colter, at his home, Tuesday, Aug. 19, 2025, in San Carlos, Calif. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

Christy Morrill, 72, who lost decades of memories to autoimmune encephalitis, poses for a photo at his home, Wednesday, Aug. 20, 2025, in San Carlos, Calif. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

Christy Morrill, 72, who lost decades of memories to autoimmune encephalitis, holds up a viewfinder with a slide film of himself as a college student, Wednesday, Aug. 20, 2025, at his home in San Carlos, Calif. (AP Photo/David Goldman)