Pretty much every debate over who should play for the national title, every argument about the staggering amounts of money, every tirade about how college football is nothing like what it used to be, traces back to a man who saw a lot of this coming, then made a lot of it happen — Roy Kramer.

Kramer, the onetime football coach who became an athletic director at Vanderbilt, then, eventually, commissioner of the Southeastern Conference where he set the template for the multibillion-dollar business college sports would become, died Thursday. He was 96.

The SEC said he died in Vonore, Tennessee.

The man who currently holds his former job, Greg Sankey, said Kramer “will be remembered for his resolve through challenging times, his willingness to innovate in an industry driven by tradition, and his unwavering belief in the value of student-athletes and education.”

Kramer helped transform his own conference from the home base for a regional pastime into the leader of a national movement during his tenure as commissioner from 1990-2002.

It was during that time that he reshaped the entire sport of college football by dreaming up the precursor to today’s playoff system — the Bowl Championship Series.

“He elevated this league and set the foundation," former Florida athletic director Jeremy Foley said. “Every decision he made was what he thought would elevate the SEC. It’s the thing that stands out most when I remember him: his passion and love for this league.”

Kramer was the first to imagine a conference title game, which divided his newly expanded 12-team league into divisions, then pitted the two champs in a winner-take-all affair that generated millions in TV revenue.

The winner of the SEC title game often had an inside track to Kramer's greatest creation, the BCS, which pivoted college football away from its long-held tradition of determining a champion via media and coaches’ polls.

The system in place from 1998 through 2013 relied on computerized formulas to determine which two teams should play in the top bowl game for the title.

That system, vestiges of which are still around today, produced its predictable share of heated debate and frustration for a large segment of the sport’s fans. Kramer, in an interview when he retired in 2002, said the BCS had been “blamed for everything from El Nino to the terrorist attacks."

But he didn't apologize. The BCS got people talking about college football in a way they never had before, he said. And besides, was it so wrong to take a baby step toward the real tournament format that virtually every other major sport used?

A four-team playoff replaced the BCS in 2014, and that was expanded to 12 teams starting last season.

Before Kramer was named commissioner, the SEC was a mostly sleepy grouping of 10 teams headlined by Bear Bryant and Alabama whose provincial rivalries were punctuated by the Sugar Bowl every year where, often, the league's best team would show what it could do against the guys up north.

Kentucky was the basketball power.

Not content with that role in the college landscape, one of Kramer's first moves was to bring Arkansas of the Southwestern Conference and independent South Carolina into the fold. That small expansion previewed a spasm of bigger reshufflings that continue to overrun this industry some 35 years later.

Kramer sold the rights to televise his newly created league title game to ABC, then in 1996 added a deal with CBS worth a then-staggering sum of $100 million over five years.

A look at some numbers tells the story that Kramer saw before most people:

— In his first year as commissioner, the SEC distributed $16.3 million to its member schools.

— In his last, in 2002, the amount rose to $95.7 million.

— In 2023-24, it was $808.4 million.

“By any standard,” former Big East commissioner Mike Tranghese said in 2002, “Roy’s influence has been mind-boggling.”

Archie Manning, the great Ole Miss quarterback who is now chair of the National Football Foundation, said Kramer's “vision, integrity, and steady leadership helped shape college football into what we know today.”

Not everyone agrees that all this change has been good.

Kramer was long gone before college sports started paying players above the table — a result of the billions those players produce, most of which had, for decades, been largely paid out only to coaches and administrators.

On Saturday, the 34th version of Kramer's SEC title game will take place in Atlanta. Virtually every big conference has followed suit, yet the future of those games has been muddled by expansion (divisions were recently phased back out because the leagues are so huge), big money and the title games' impact, or lack of impact, on the expanded playoff field.

On Sunday, the bracket for this year's 12-team tournament will come out. Kramer's old school, 14th-ranked Vanderbilt, is likely to be left out despite a historically great 10-2 season that Commodores fans will argue is something to be celebrated, not ignored.

Vandy wouldn't have been in under the old system either, but part of Kramer's legacy is that the bowl games that defined this sport back in the day have been reduced to near irrelevance. Vanderbilt's postseason turn this season will likely be nothing more than a holiday-season afterthought. And a spot in the Sugar Bowl today only means something if it's part of that playoff.

Roy Foster Kramer was born Oct. 30, 1929 in Maryville, Tennessee. He earned a bachelor’s degree from Maryville College, where he was a football lineman and wrestler.

He was named head coach at Central Michigan in 1965 and earned national coach-of-the-year honors there in 1974 after winning the Division II national championship. Kramer ended his coaching career in 1978 when he became athletic director at Vanderbilt, where he served until leaving for the SEC.

Quick with a quip and slow to true anger, Kramer did most of his work behind the scenes. He was reluctant to sit for interviews and didn't much like the spotlight — or the idea that he was reshaping college sports.

Foley, the former Florida AD, recalled rushing into a locker room full of umpires to berate them after he thought they'd robbed the Gators baseball team with a bad call.

The next day, there was no mass email to media announcing a fine for the AD, no penalty being meted out to the program, no appearance on ESPN by the commish to discuss the confrontation.

But Foley's phone rang. It was Kramer.

“'That can never, ever happen again,'" Foley recalled Kramer telling him. "That was his style. He wasn’t a grandstander or a showman. He had an unbelievable ability to read people and deal with people.”

AP Sports Writers Mark Long and Dave Campbell contributed to this report.

Get poll alerts and updates on the AP Top 25 throughout the season. Sign up here and here (AP News mobile app). AP college football: https://apnews.com/hub/ap-top-25-college-football-poll and https://apnews.com/hub/college-football

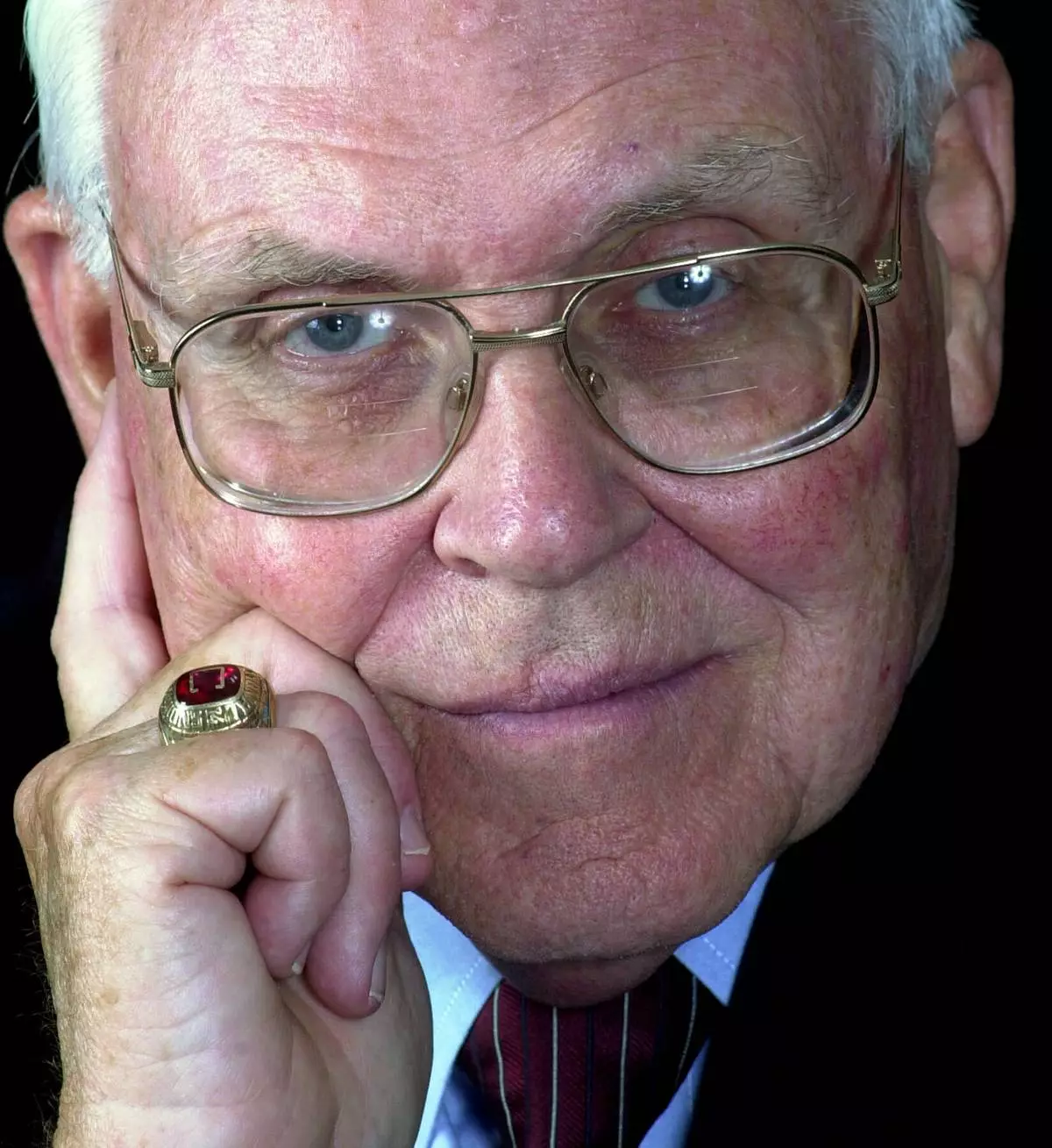

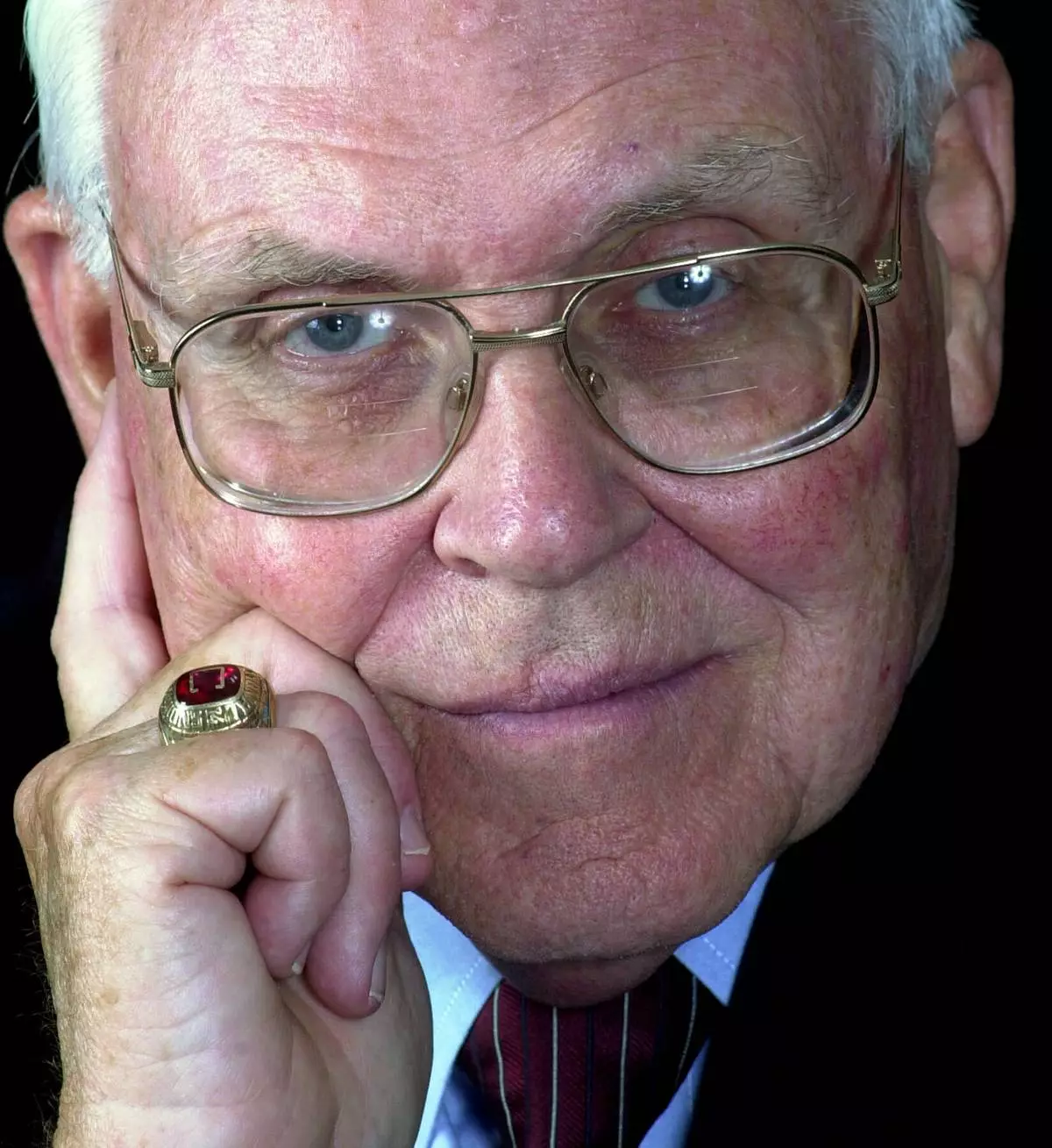

FILE - Southeastern Conference Commissioner Roy Kramer is pictured at the SEC headquarters in Birmingham, Ala., Tuesday, June 6, 2000. (AP Photo/Dave Martin, File)

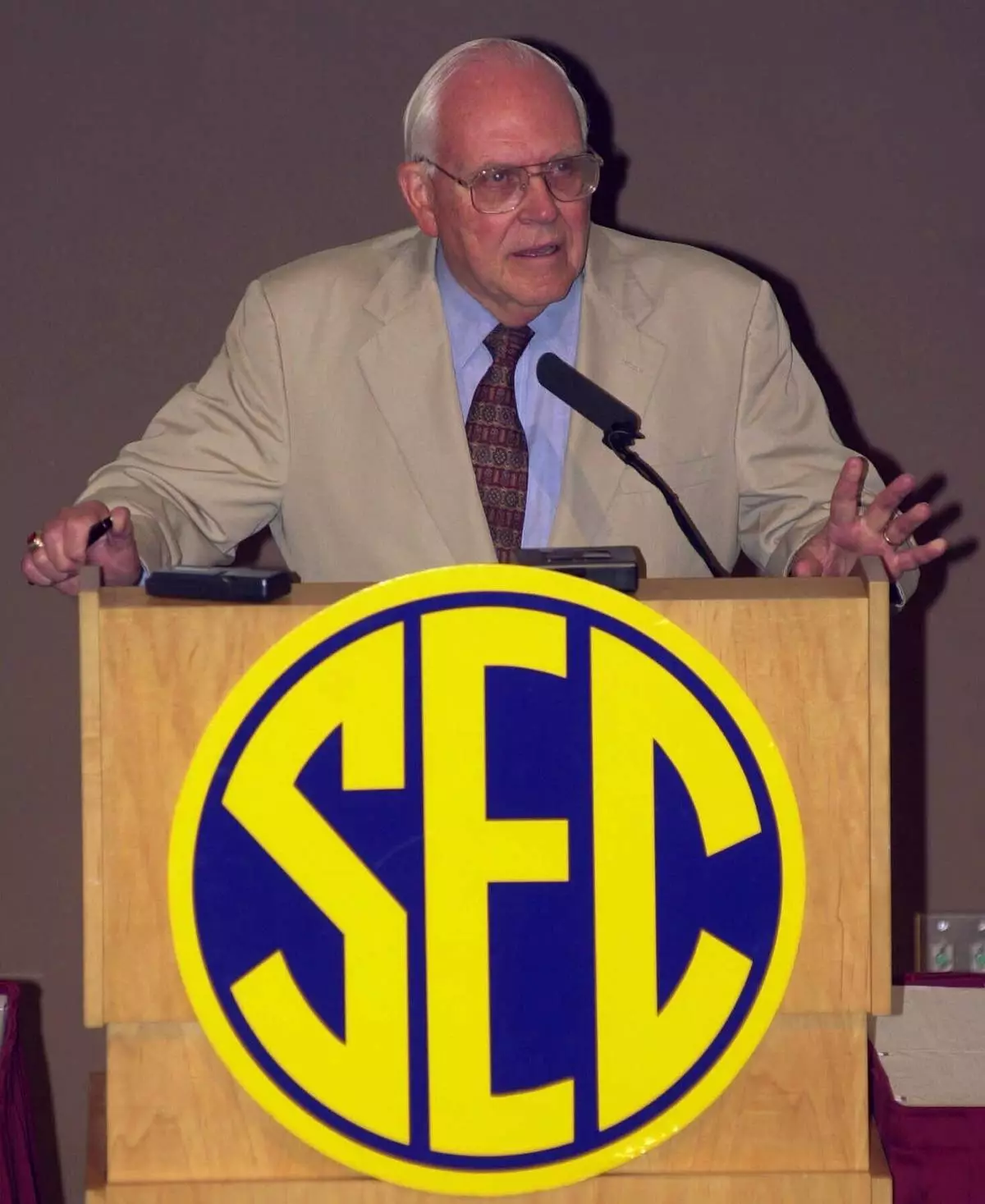

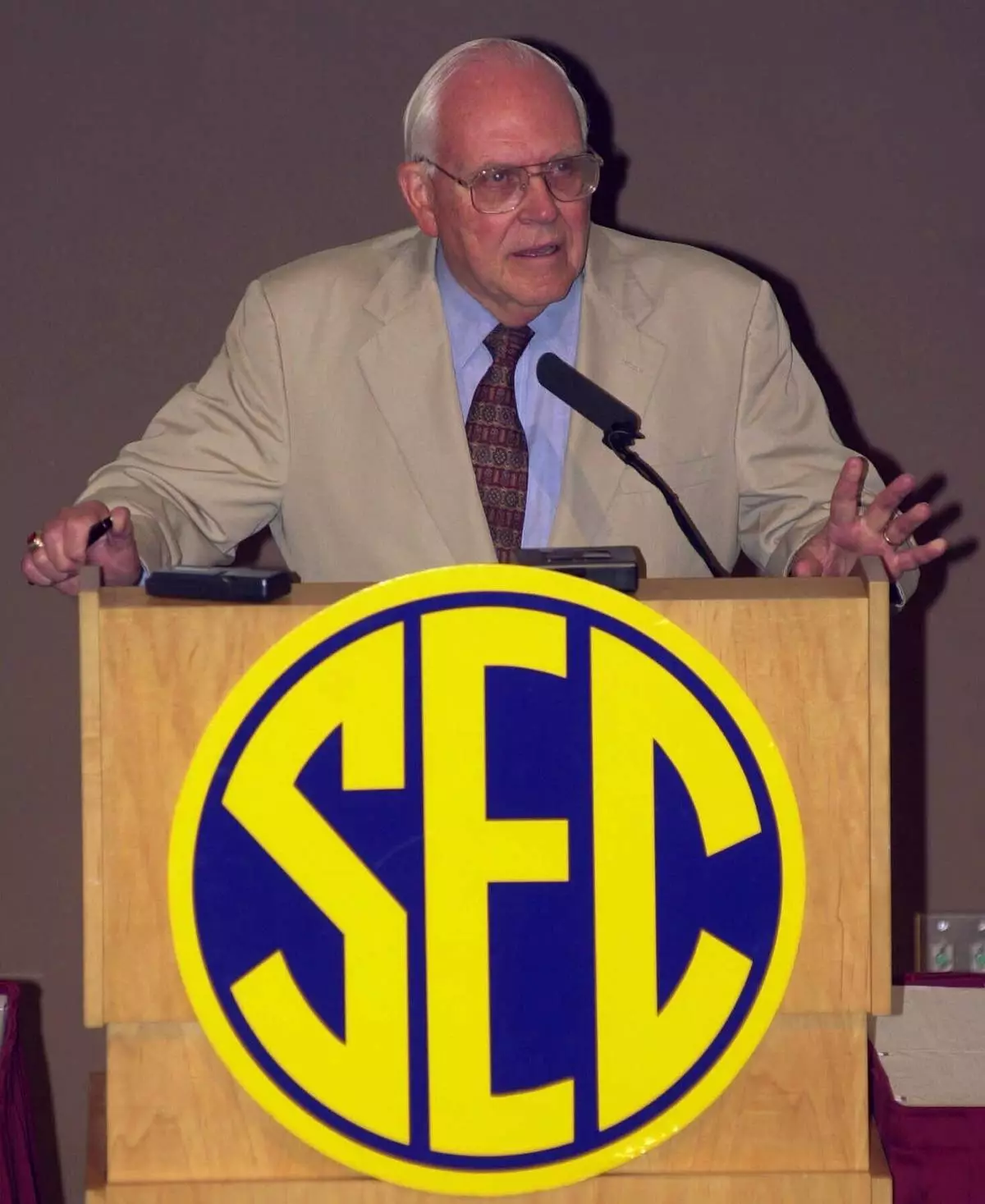

FILE - Southeastern Conference Commissioner Roy Kramer talks with reporters during the opening session of the Southeastern Conference football media days in Birmingham, Ala., on Tuesday, July 25, 2000. (AP Photo/Dave Martin, File)

FILE - Roy Kramer, former commissioner , Southeastern Conference, listens to Mack Brown, Head Football Coach for The University of Texas, during his opening statement for the panel discussion for "Ethical Issues in College Athletics" in the Daniel-Meyer Coliseum on the Texas Christian University Campus, Thursday, Feb., 12, 2004. (AP Photo/David Pellerin, File)

DUBAI, United Arab Emirates (AP) — Iran’s secretive new leader issued his first public statements Thursday, resolving to keep fighting, promising more pain for Gulf Arab states and threatening to open “other fronts” in a war that has already disrupted world energy supplies, the global economy and international travel.

Early Friday, U.S. President Donald Trump issued a new threat online to Iran, writing: “Watch what happens to these deranged scumbags today.” Trump tallied the damage inflicted on Iran and its leaders and called it a “great honor” to be responsible for it.

The remarks by Supreme Leader Ayatollah Mojtaba Khamenei came as Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said his country's attacks were creating conditions for the Iranian population to topple the government.

“It is in your hands,” Netanyahu said at a news conference, addressing the Iranian people. “We are creating the optimal conditions for the fall of the regime.”

Since the start of the war, U.S. and Israeli strikes have targeted security checkpoints in Iran to undermine the government’s ability to suppress dissent, according to Armed Conflict Location and Event Data, the U.S-based independent monitoring group known as ACLED.

Intense airstrikes hit early Friday around Iran’s capital, Tehran, as well as outlying areas. It was not immediately clear what had been targeted.

Netanyahu denounced Khamenei as a “puppet of the Revolutionary Guards."

Khamenei is close to Iran’s paramilitary Revolutionary Guard and is widely seen as even less compromising than his father, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Khamenei said in a statement read by a state TV news anchor that he was keeping a “file of revenge.” He did not appear on camera and has not been seen since his father and wife were killed in the war’s opening salvo, which also wounded him, according to an Iranian ambassador.

The war continued to escalate on its 13th day as oil prices spiraled up again to $100 per barrel, and stocks sank worldwide over fears that the conflict could drag on longer than hoped.

To relieve the surge in prices, the U.S. Treasury Department announced it was further easing sanctions on Russian oil by granting a license that authorizes the delivery and sale of some Russian crude oil and petroleum products for the next month.

Trump signaled earlier this week that he would take more action to address the squeeze on oil flows. The move follows the administration’s decision to grant temporary permission for India to buy Russian oil.

The new exemption applies only to Russian oil already at sea. Last week, analysts estimated there were about 125 million barrels loaded on tankers. To put that in perspective, about 20 million barrels of oil per day usually pass through the Strait of Hormuz, according to the International Energy Agency.

Iran has made clear it plans to keep up attacks on energy infrastructure across the region and use the effective closure of the strait as leverage against the United States and Israel. A fifth of the world’s traded oil flows through the waterway leading from the Persian Gulf toward the Indian Ocean.

At a news conference Thursday, Iran’s ambassador to Tunisia, Mir Masoud Hosseinian, said Iranian naval forces “have established full control” over the strait and “carried out precise strikes in response to attacks on our oil infrastructure.”

“Global energy security is contingent on respect for Iran’s sovereignty,” he said.

The pinch was being felt worldwide. South Korea reinstated government-set caps on oil prices for the first time in three decades as it sought to calm soaring fuel costs. The two-week caps, which took effect Friday, set maximum prices for petroleum products supplied by refiners to gas stations and other businesses.

Hosseinian told The Associated Press the new supreme leader was wounded in the attack on his family’s home, but “it is not serious.” The hope is he will attend the massive, state-organized Eid prayer next week that his father traditionally led. However, Khamenei remains a target for the Israelis, who have vowed to kill him.

Hosseinian said Iran’s strikes on Gulf nations have been strategic. “Even when we targeted hotels, we had precise information that they were hosting American and Israeli soldiers,” he said.

Khamenei called on Gulf Arabs to “shut down” U.S. bases in the region, saying protection promised by Washington was “nothing more than a lie.”

He also said Iran has studied “opening other fronts in which the enemy has little experience and would be highly vulnerable” if the war continues. He did not elaborate, but Iran has been linked to previous attacks on U.S., Israeli and Jewish targets around the world.

Attacks on Gulf states continued Friday with Saudi Arabia’s defense ministry saying its air defenses downed more than three dozen drones headed toward the kingdom’s Eastern Province over the span of a few hours, marking an unusually large barrage.

Trump said in a social media post Thursday that ensuring Iran does not develop a nuclear weapon was a higher priority than soaring oil prices.

Hours later, Netanyahu announced Israeli attacks had killed a top Iranian nuclear scientist and hit others but gave few details.

Israel said earlier it struck a nuclear facility in Iran in recent days that it had destroyed with an airstrike in October 2024. Earlier this year, satellite photos raised concerns that Iran was working to restore the facility.

The U.S. military said American forces have now struck more than 6,000 targets since the operation against Iran began, including more than 30 minelaying vessels.

On Friday, French President Emmanuel Macron said a French soldier was killed in an attack targeting Irbil in Iraq's northern Kurdish region. France earlier said six soldiers had been hurt in a drone strike in Irbil, where French troops are deployed as part of a multinational counterterrorism mission supporting Iraqi forces in their fight against Islamic State militants.

In the same region, British officials said several U.S. personnel suffered minor injuries Wednesday when drone strikes hit a base in Irbil that houses both British and American troops.

And on Thursday in western Iraq, rescue efforts were underway after an American military refueling plane went down. U.S. Central Command, which oversees the Middle East, said in a statement that two aircraft were involved, including one that landed safely, and that the cause was not related to friendly or hostile fire.

Israeli warplanes pummeled Lebanon, targeting even the busy heart of Beirut, in response to missiles from Iran-backed Hezbollah fighters launched into Israel. One strike hit in a neighborhood that is close to Lebanon’s parliament, United Nations offices and international embassies.

Israeli military spokesperson Avichay Adraee said forces were targeting a “facility affiliated with Hezbollah.”

An Israeli strike hit in the vicinity of Lebanon’s only public university, killing a professor and the director of the science faculty at the campus in Hadath, on the outskirts of Beirut’s southern suburbs. There was no immediate comment from Israel.

Israeli strikes also killed 15 other people, including five children, in southern Lebanon, the Lebanese Health Ministry said. An AP photographer saw several buildings flattened in one village where rescue workers searched through the rubble.

Ben Mbarek reported from Tunis, Tunisia. El Deeb reported from Beirut. Watson reported from San Diego. Associated Press writers from around the world contributed to this report.

Israeli authorities inspect homes damaged by a projectile launched from Lebanon, in Haniel, central Israel, Thursday, March 12, 2026. (AP Photo/Baz Ratner)

Residents watch as smoke rises from a nearby building during an Israeli strike in central Beirut, Lebanon, Thursday, March 12, 2026. (AP Photo/Hussein Malla)

A woman gathers belongings from her family's home after it was damaged by a projectile launched from Lebanon, in Haniel, central Israel, Thursday, March 12, 2026. (AP Photo/Baz Ratner)

People inspect homes damaged by a projectile launched from Lebanon, in Haniel central Israel, Thursday, March 12, 2026. (AP Photo/Baz Ratner)

Workers inspect damage caused by a drone strike overnight at the Address Creek Harbour hotel in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, March 12, 2026. (AP Photo/Fatima Shbair)

An oil tanker burns after being hit by an Iranian strike in the ship-to-ship transfer zone at Khor al-Zubair port near Basra, Iraq, late Wednesday, March 11, 2026. (AP Photo)

A woman sits on rubble across from a residential building damaged last Monday during the U.S.-Israeli air campaign in Tehran, Iran, Thursday, March 12, 2026. (AP Photo/Vahid Salemi)

Israeli authorities inspect homes damaged by a projectile launched from Lebanon, in Haniel central Israel, Thursday, March 12, 2026. (AP Photo/Baz Ratner)

Israel Ambassador to the United Nations Danny Danon speaks during a meeting of the Security Council at U.N. headquarters, Wednesday, March 11, 2026. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

A family enjoys the sunset with the view of the city skyline and Burj Khalifa, at Dubai Creek Harbour in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, Wednesday, March 11, 2026. (AP Photo/Fatima Shbair)

Oil tankers and cargo ships line up in the Strait of Hormuz as seen from Khor Fakkan, United Arab Emirates, Wednesday, March 11, 2026. (AP Photo/Altaf Qadri)

Smoke rises after an explosion at the airport in Irbil, Iraq, late Wednesday, March 11, 2026. (AP Photo/Leo Correa)

A man inspects a car damaged in an Israeli airstrike at the Ramlet al-Baida public beach in Beirut, Lebanon, early Thursday, March 12, 2026. (AP Photo/Bilal Hussein)