After decades of political maneuvering through Congress and government agencies, the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina may finally achieve federal recognition through the National Defense Authorization Act the House plans to vote on this week.

If the legislation passes, the Senate could vote on final passage as soon as next week.

The Lumbee’s efforts to gain federal recognition — which would come with federal funding, access to resources like the Indian Health Service and the ability to take land into trust — have been controversial for many years both in Indian Country and in Washington. But their cause has been championed by President Donald Trump, who promised on the campaign trail last year to acknowledge the Lumbee as a tribal nation.

The issue of federal recognition for the Lumbee Tribe has been batted around Congress for more than thirty years. But the political opportunity it represented in the last election could be what pushed it over the finish line, said Kevin Washburn, former assistant secretary of Indian Affairs at the Interior Department and a professor at the University of California, Berkeley School of Law.

“It comes up every four years because North Carolina is a battleground state and the Lumbee represent tens of thousands of people,” Washburn said.

The Lumbee Tribe has nearly 60,000 members, and both Trump and Democratic candidate Kamala Harris promised the Lumbee federal recognition during the 2024 campaign. Trump won North Carolina by more than 3 points. Shortly after taking office, Trump issued an executive order directing the Interior Department to create a plan for federal recognition for the Lumbee.

It's the first time either the White House or the candidates for president have been so engaged in a federal recognition case, Washburn said.

Interior's plan was sent to the White House in April. The administration has denied requests for its release but has said it advised the Lumbee to continue trying to gain federal recognition through Congress.

The Lumbee were recognized by Congress in 1956, but that legislation denied them access to the same federal resources as tribal nations. As a result, their application for recognition was denied for consideration in the 1980s, and the Lumbee Tribe has tried to get Congress to acknowledge them in the decades since. The Office of Federal Acknowledgement is the federal agency that vets applications, although dozens of tribes have also gained recognition through legislation.

“Only Congress can for all time and for all purposes resolve this uncertainty,” Lumbee Tribal Chairman John Lowery testified last month before the Senate Committee for Indian Affairs. “It is long past time to rectify the injustice it has inflicted on our tribe and our people.”

But others, including several tribal leaders, argue that the Lumbee's historic claims have shifted many times over the last century and that they have never been able to prove they descend from a tribal nation.

“A national defense bill is not the appropriate place to consider federal recognition, particularly for a group that has not met the historical and legal standards required of sovereign tribal nations,” said Michell Hicks, chief of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians.

The National Defense Authorization Act is usually a bipartisan bill that lays out the nation’s defense policies. But this year the vote has taken on a new political dynamic as Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth faces mounting scrutiny over military strikes on boats off Venezuela’s coast.

__

The story corrects the name of the Eastern Band chief to Michell Hicks, not Michelle.

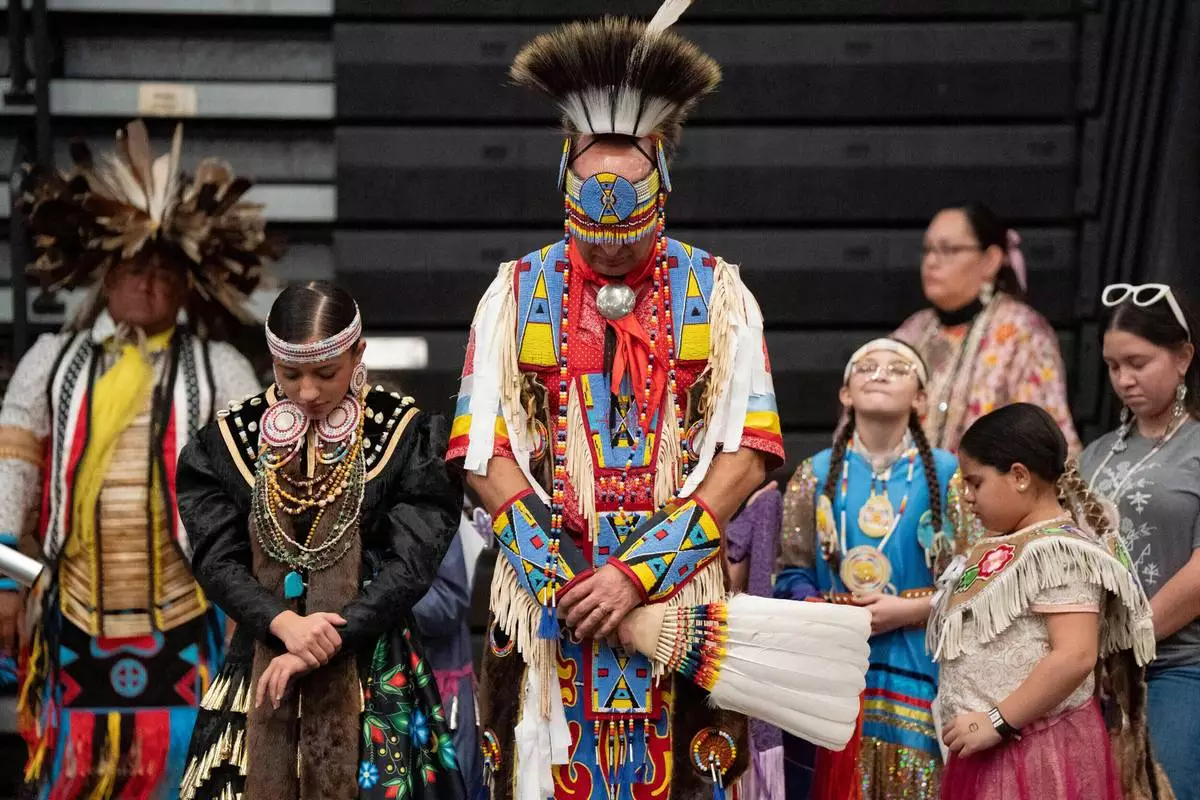

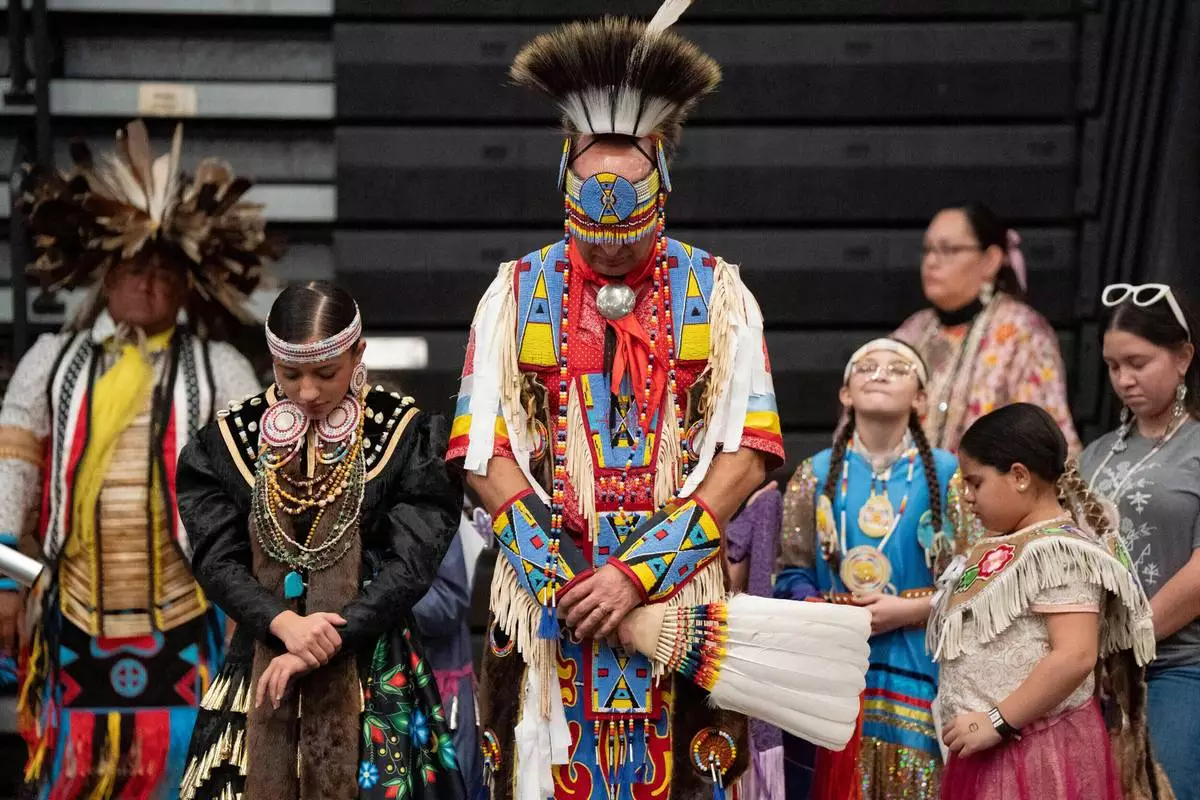

FILE - Members of the Lumbee Tribe bow their heads in prayer during the BraveNation Powwow and Gather at UNC Pembroke, March 22, 2025, in Pembroke, N.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce, file)

Ethiopia 's prime minister loves big projects. With a mega-dam completed on the Nile, Abiy Ahmed now plans Africa's largest airport and a nuclear power plant. But the threat of war is back as the landlocked nation seeks its most audacious feat yet: access to the sea.

The prime minister hailed the country's transformation in a parliamentary address in late October. The capital, Addis Ababa, has seen a development boom. The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam was inaugurated in July. Abiy has called it a “harbinger of tomorrow’s dawn” that will end the reliance on foreign aid for Africa's second most populous nation. The country has been one of the world's biggest aid recipients.

But multiple challenges lie ahead that could badly damage the economy, which has seen some of the strongest growth on the continent.

Abiy’s government is determined to regain access to the Red Sea, which Ethiopia lost when Eritrea seceded in 1993 after decades of guerrilla warfare.

The countries made peace in recent years, bringing Abiy a Nobel Peace Prize, then teamed up for a devastating war against Ethiopia's Tigray region. Now tensions have returned.

In June, Eritrea accused Ethiopia of having a “long-brewing war agenda” aimed at seizing its Red Sea ports. Ethiopia insists it wants to gain sea access peacefully.

Ethiopia recently claimed Eritrea was “actively preparing to wage war against it." It has also accused Eritrea of supporting Ethiopian rebel groups.

Magus Taylor, deputy Horn of Africa director at the International Crisis Group, described the tensions as concerning.

“There’s a possibility of mistakes or miscalculation,” he said. “And the situation could deteriorate further in the coming months.”

Egypt relies on the Nile for nearly all its drinking water and fiercely opposed the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, asserting that it would threaten the supply. Egypt and Ethiopia have held several rounds of inconclusive talks to regulate the use of the dam, especially in times of drought.

Since the dam's inauguration, Cairo has toughened its rhetoric against Ethiopia. In September, it said it reserved “the right to take all necessary measures … to defend the existential interests of its people.”

Ethiopia says the dam is critical for its development as it seeks to lift millions of people out of poverty.

Egypt has also sought to exploit tensions between Ethiopia and its neighbors. It has bolstered security ties with Eritrea and signed a security pact with Somalia, which last year reacted furiously when Ethiopia signed a port deal with the breakaway region of Somaliland, over which Somalia claims sovereignty.

The war in Ethiopia's Tigray region ended with a peace deal in late 2022, but the country's two largest regions — Amhara and Oromia — are wracked by ethnic-based insurgencies that threaten internal security.

Both the group of loosely organized militias called Fano in Amhara, and the Oromo Liberation Army Oromia, claim to represent those oppressed by the federal government.

Witnesses have reported massacres and other extrajudicial killings by all sides. Kidnapping for ransom has become commonplace, and humanitarian aid groups struggle to deliver supplies.

Amnesty International has described the cycle of violence as a “revolving door of injustices.”

Meanwhile, the peace deal for Tigray risks unraveling. Southern areas of Tigray have seen clashes between regional forces and local militias aligned with the federal government. Tigray’s rulers accused the federal government of “openly breaching” the agreement after a drone strike hit its forces.

Abiy's government now accuses Tigray’s rulers of colluding with Eritrea.

The insecurity contrasts starkly with the mood in Addis Ababa, where Abiy has spent billions of dollars on a face lift that has included creating bike lanes, a conference center, parks and museums.

The prime minister wants to turn the capital, already home to the African Union continental body and one of Africa's busiest airports, into a hub for international tourists and investors.

He has floated Ethiopia’s currency, opened the banking sector and launched a stock exchange — all dramatic steps for a country where the economy has long been state-owned and state-managed.

The reforms helped Ethiopia secure a $3.4 billion bailout from the International Monetary Fund last year. But investors are wary about Ethiopia’s internal insecurity and tensions with its neighbors.

Poverty, meanwhile, has risen alarmingly. About 43% of Ethiopians now live under the poverty line, up from 33% in 2016, two years before Abiy took power, according to the World Bank. That's due in part to rising food and fuel prices as well as defense spending taking up more of Ethiopia's budget.

The sense of prosperity prevailing in Addis Ababa is not shared by Ethiopia’s regions, said Taylor with the International Crisis Group.

“Abiy has a firm grip on the country at the center, but then you have these periphery conflicts partly based on feelings of injustice – that they are poor and the center is rich,” he said. “So we expect this kind of instability to continue in these areas.”

For more on Africa and development: https://apnews.com/hub/africa-pulse

The Associated Press receives financial support for global health and development coverage in Africa from the Gates Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

FILE - Fighters loyal to the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF) walk along a street in the town of Hawzen, then controlled by the group, in the Tigray region of northern Ethiopia, May 7, 2021. (AP Photo/Ben Curtis, File)

FILE - A destroyed tank is seen by the side of the road south of Humera, in an area of western Tigray, annexed by the Amhara region during the ongoing conflict, in Ethiopia, May 1, 2021. (AP Photo/Ben Curtis, File)

FILE - An Ethiopian woman argues with others over the allocation of yellow split peas after it was distributed by the Relief Society of Tigray in the town of Agula, in the Tigray region of northern Ethiopia, May 8, 2021. (AP Photo/Ben Curtis, File)

FILE - A view of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, in Benishangul-Gumuz, Ethiopia, Sept. 9, 2025. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - Ethiopia's Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed Ali delivers a speech during the inauguration of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, in Benishangul-Gumuz, Ethiopia, Sept. 9, 2025. (AP Photo, File)