WASHINGTON (AP) — Not long after President Donald Trump took office in January, staff at CentroNía bilingual preschool began rehearsing what to do if Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials came to the door. As ICE became a regular presence in their historically Latino neighborhood this summer, teachers stopped taking children to nearby parks, libraries and playgrounds that had once been considered an extension of the classroom.

And in October, the school scrapped its beloved Hispanic Heritage Month parade, when immigrant parents typically dressed their children in costumes and soccer jerseys from their home countries. ICE had begun stopping staff members, all of whom have legal status, and school officials worried about drawing more unwelcome attention.

All of this transpired before ICE officials arrested a teacher inside a Spanish immersion preschool in Chicago in October. The event left immigrants who work in child care, along with the families who rely on them, feeling frightened and vulnerable.

Trump’s push for the largest mass deportation in history has had an outsized impact on the child care field, which is heavily reliant on immigrants and already strained by a worker shortage. Immigrant child care workers and preschool teachers, the majority of whom are working and living in the U.S. legally, say they are wracked by anxiety over possible encounters with ICE officials. Some have left the field, and others have been forced out by changes to immigration policy.

At CentroNía, CEO Myrna Peralta said all staff must have legal status and work authorization. But ICE's presence and the fear it generates have changed how the school operates.

“That really dominates all of our decision making,” Peralta said.

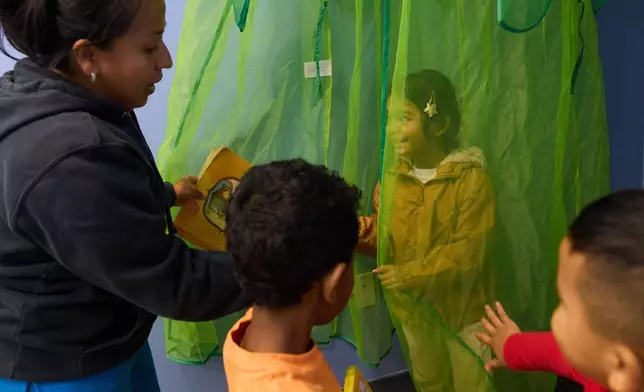

Instead of taking children on walks through the neighborhood, staff members push children on strollers around the hallways. And staff converted a classroom into a miniature library when the school scrapped a partnership with a local library.

Schools and child care centers were once off limits to ICE officials, in part to keep children out of harm’s way. But those rules were scrapped not long after Trump's inauguration. Instead, ICE officials are urged to exercise “common sense.”

Tricia McLaughlin, spokesperson for the Department of Homeland Security, defended ICE officials' decision to enter the Chicago preschool. She said the teacher, who had a work permit and was later released, was a passenger in a car that was being pursued by ICE officials. She got out of the car and ran into the preschool, McLaughlin said, emphasizing the teacher was “arrested in the vestibule, not in the school.” The man who had been driving went inside the preschool, where officials arrested him.

About one-fifth of America’s child care workers were born outside the United States and one-fifth are Latino. The proportion of immigrants in some places, particularly large cities, is much higher: In the District of Columbia, California and New York, around 40% of the child care workforce is foreign-born, according to UC Berkeley’s Center for the Study of Child Care Employment.

Immigrants in the field tend to be better educated than those born in the United States. Those from Latin America help satisfy the growing demand for Spanish-language preschools, such as CentroNía, where some parents enroll their kids to give them a head start learning another language.

The American Immigration Council estimated in 2021 that more than three-quarters of immigrants working in early care and education were living and working in the U.S. legally. Preschools like CentroNía conduct rigorous background checks, including verifying employees have work authorization.

Beyond the deportation efforts, the Trump administration in recent months has stripped legal status from hundreds of thousands of immigrants. Many of them had fled violence, poverty or natural disasters in their homes and received Temporary Protected Status, which allowed them to live and work legally in the U.S. But Trump ended those programs, forcing many out of their jobs — and the country. Just last month, 300,000 immigrants from Venezuela lost their protected status.

CentroNía lost two employees when they lost their TPS, Peralta said, and a Nicaraguan immigrant working as a teacher left on his own. Tierra Encantada, which runs Spanish immersion preschools in several states, had a dozen teachers leave when they lost their TPS.

At CentroNía, one staff member was detained by ICE while walking down the street and held for several hours, all the while unable to contact colleagues to let them know where she was. She was released that evening, said the school's site director, Joangelee Hernández-Figueroa.

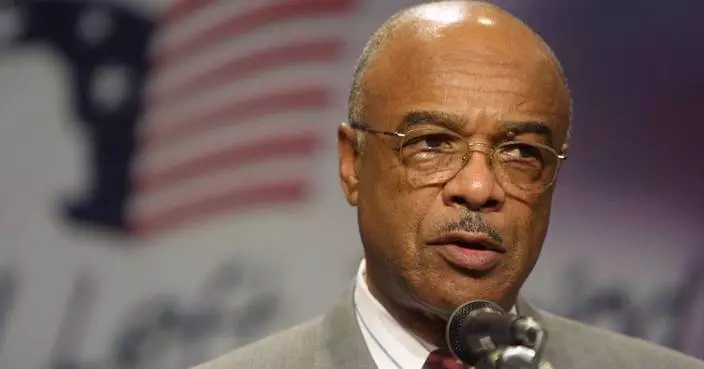

Another staff member, teacher Edelmira Kitchen, said she was pulled over by ICE on her way to work in September. Officials demanded she get out of her car so they could question her. Kitchen, a U.S. citizen who immigrated from the Dominican Republic as a child, said she refused and they eventually let her go.

“I felt violated of my rights," Kitchen said.

Hernández-Figueroa said ICE's heightened presence during the federal intervention in the city has taken a toll on employees' mental health. Some have gone to the hospital with panic attacks in the middle of the school day.

When the city sent mental health consultants to the school earlier this year as part of a partnership with the Department of Behavioral Health, school leadership had them work with teachers rather than students, worried their anguish would spill over to the classroom.

“If the teachers aren't good,” Hernández-Figueroa said, “the kids won't be good either.”

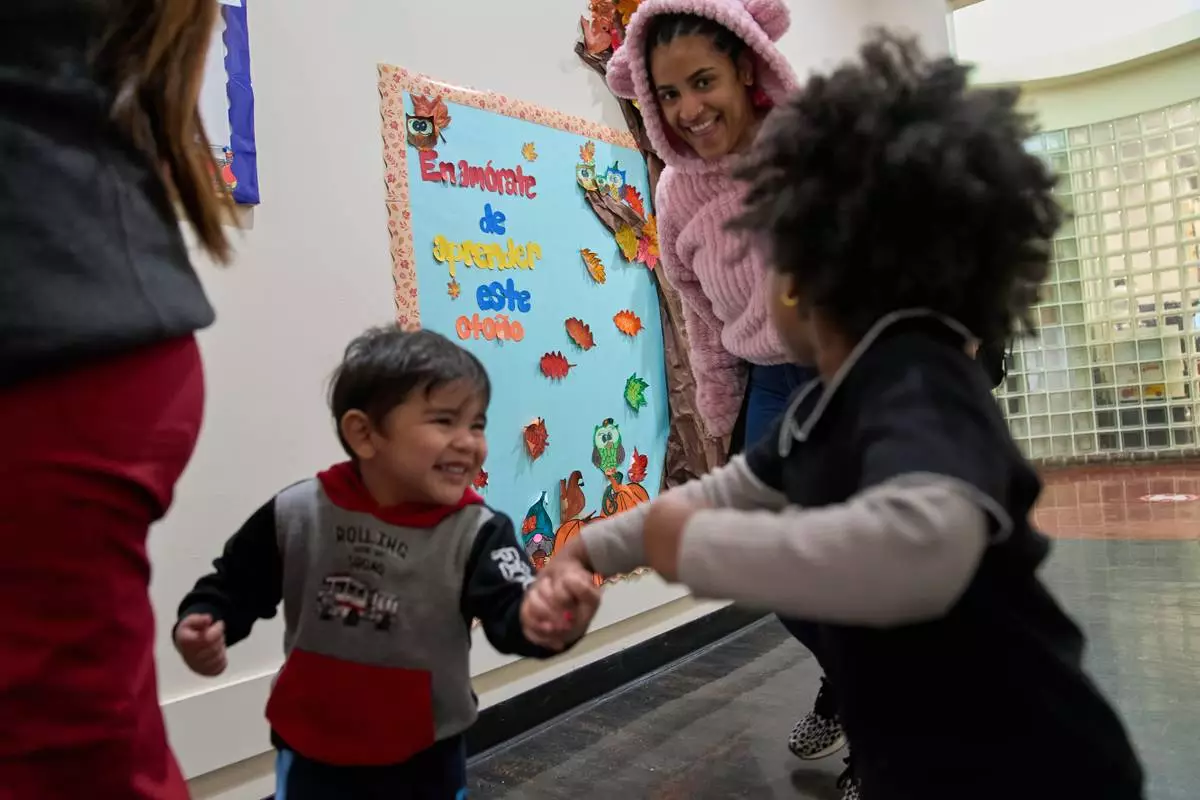

It's not just adults who are feeling more anxious. At a Guidepost Montessori School in Portland, Oregon, teachers observed preschoolers change in the weeks after an ICE arrest near the school in July. After pulling over a father who was driving his child to the school, officials encountered him in the school parking lot and tried to arrest him. In the ensuing commotion, the school went into lockdown: Children were pulled off the playground, and teachers played loud music and had children sing along to drown out the yelling.

Amy Lomanto, who heads the school, said teachers noticed more outbursts among students, and more students retreating to what the school calls “the regulation station,” an area in the main office with fidget toys kids can use to calm themselves.

She said what unfolded at her school underscored that even wealthy communities, like the one the school serves, are not immune from exposure to these kinds of events.

“With the current situation, more and more of us are likely to experience this kind of trauma,” she said. “That level of fear now is permeating a lot more throughout our society.”

The Associated Press’ education coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Celenia Romero reads to her Prek-5 students as they play in the library at CentroNia in Washington, Tuesday, Dec. 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin)

Edelmira Kitchen, a teaching artist at CentroNia, poses for a portrait in a classroom at CentroNia in Washington, Tuesday, Dec. 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin)

Celenia Romero reads to her Prek-5 students in the library at CentroNia in Washington, Tuesday, Dec. 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin)

Edelmira Kitchen, a teaching artist at CentroNia, poses for a portrait in a classroom at CentroNia in Washington, Tuesday, Dec. 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin)

Celenia Romero reads to her Prek-5 students in the library at CentroNia in Washington, Tuesday, Dec. 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin)

Belkis Mendez, builds with a Prek-5 student during playtime in their classroom at CentroNia in Washington, Tuesday, Dec. 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin)

Flor Perez encourages her class of 2-year-olds in a walk around the school in lieu of outdoor walks around the neighborhood during school time at CentroNia in Washington, Tuesday, Dec. 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin)

Families leave CentroNia at the end of the school day in Washington, Tuesday, Dec. 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin)