MIAMI (AP) — President Donald Trump’s zero-tolerance immigration policy split more than 5,000 children from their families at the Mexico border during his first term, when images of babies and toddlers taken from the arms of mothers sparked global condemnation.

Seven years later, families are being separated but in a much different way. With illegal border crossings at their lowest levels in seven decades, a push for mass deportations is dividing families of mixed legal status inside the U.S.

Federal officials and their local law enforcement partners are detaining tens of thousands of asylum-seekers and migrants. Detainees are moved repeatedly, then deported, or held in poor conditions for weeks or months before asking to go home.

The federal government was holding an average of more than 66,000 people in November, the highest on record.

During the first Trump administration, families were forcibly separated at the border and authorities struggled to find children in a vast shelter system because government computer systems weren't linked. Now parents inside the United States are being arrested by immigration authorities and separated from their families during prolonged detention. Or, they choose to have their children remain in the U.S. after an adult is deported, many after years or decades here.

The Trump administration and its anti-immigration backers see “unprecedented success" and Trump’s top border adviser Tom Homan told reporters in April that “we’re going to keep doing it, full speed ahead.”

Three families separated by migration enforcement in recent months told The Associated Press that their dreams of better, freer lives had clashed with Washington’s new immigration policy and their existence is anguished without knowing if they will see their loved ones again.

For them, migration marked the possible start of permanent separation between parents and children, the source of deep pain and uncertainty.

Antonio Laverde left Venezuela for the U.S. in 2022 and crossed the border illegally, then requested asylum.

He got a work permit and a driver’s license and worked as an Uber driver in Miami, sharing homes with other immigrants so he could send money to relatives in Venezuela and Florida.

Laverde's wife Jakelin Pasedo and their sons followed him from Venezuela to Miami in December 2024. Pasedo focused on caring for her sons while her husband earned enough to support the family. Pasedo and the kids got refugee status but Laverde, 39, never obtained it and as he left for work one early June morning, he was arrested by federal agents.

Pasedo says it was a case of mistaken identity by agents hunting for a suspect in their shared housing. In the end, she and her children, then 3 and 5, remember the agents cuffing Laverde at gunpoint.

“They got sick with fever, crying for their father, asking for him,” Pasedo said.

Laverde was held at Broward Transitional Center, a detention facility in Pompano Beach, Florida. In September, after three months detention, he asked to return to Venezuela.

Pasedo, 39, however, has no plans to go back. She fears she could be arrested or kidnapped for criticizing the socialist government and belonging to the political opposition.

She works cleaning offices and, despite all the obstacles, hopes to reunify with her husband someday in the U.S.

Yaoska’s husband was a political activist in Nicaragua, a country tight in the grasp of autocratic married co-presidents Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo.

She remembers her husband getting death threats and being beaten by police when he refused to participate in a pro-government march.

Yaoska only used her first name and requested anonymity for her husband to protect him from the Nicaraguan government.

The couple fled Nicaragua for the U.S. with their 10-year-old son in 2022, crossing the border and getting immigration parole. Settling down in Miami, they applied for asylum and had a second son, who has U.S. citizenship. Yaoska is now five months pregnant with their third child.

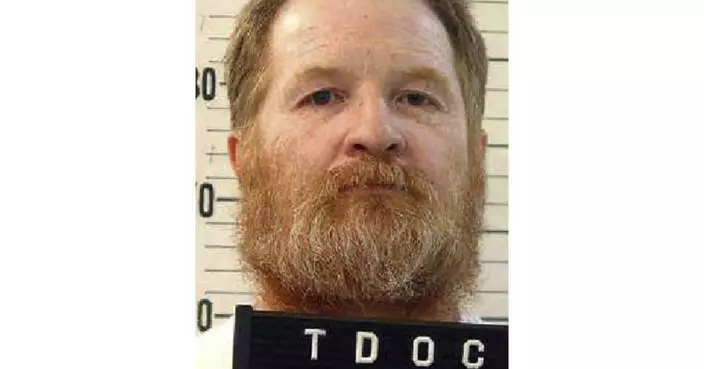

In late August, Yaoska, 32, went to an appointment at the South Florida office of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Her family accompanied her. Her husband, 35, was detained and failed his credible fear interview, according to a court document.

Yaoska was released under 24-hour supervision by a GPS watch that she cannot remove. Her husband was deported to Nicaragua after three months at the Krome Detention Center, the United States’ oldest immigration detention facility and one with a long history of abuse.

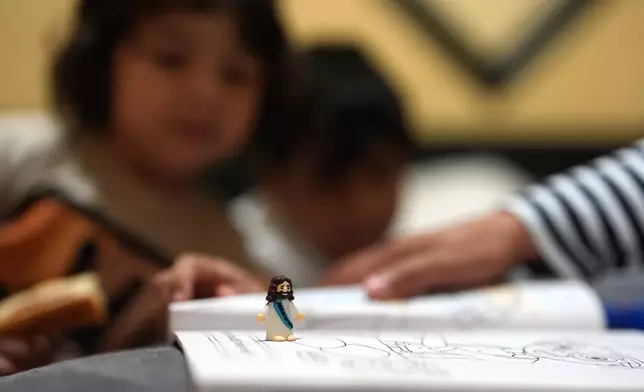

Yaoska now shares family news with her husband by phone. The children are struggling without their father, she said.

“It’s so hard to see my children like this. They arrested him right in front of them,” Yaoska said, her voice trembling.

They don’t want to eat and are often sick. The youngest wakes up at night asking for him.

“I’m afraid in Nicaragua,” she said. “But I’m scared here too.”

Yaoska said her work authorization is valid until 2028 but the future is frightening and uncertain.

“I’ve applied to several job agencies, but nobody calls me back,” she said. “I don’t know what’s going to happen to me."

Edgar left Guatemala more than two decades ago. Working construction, he started a family in South Florida with Amavilia, a fellow undocumented Guatemalan migrant.

The arrival of their son brought them joy.

“He was so happy with the baby — he loved him,” said Amavilia, 31. “He told me he was going to see him grow up and walk.”

But within a few days, Edgar was detained on a 2016 warrant for driving without a license in Homestead, the small agricultural city where he lived in South Florida.

She and her husband declined to provide their last names because they are worried about repercussion from U.S. immigration officials.

Amavilia expected his release within 48 hours. Instead, Edgar, who declined to be interviewed, was turned over to immigration officials and moved to Krome.

“I fell into despair. I didn’t know what to do,” Amavilia said. “I can’t go.”

Edgar, 45, was deported to Guatemala on June 8.

After Edgar’s detention, Amavilia couldn’t pay the $950 rent for the two-bedroom apartment she shares with another immigrant. For the first three months, she received donations from immigration advocates.

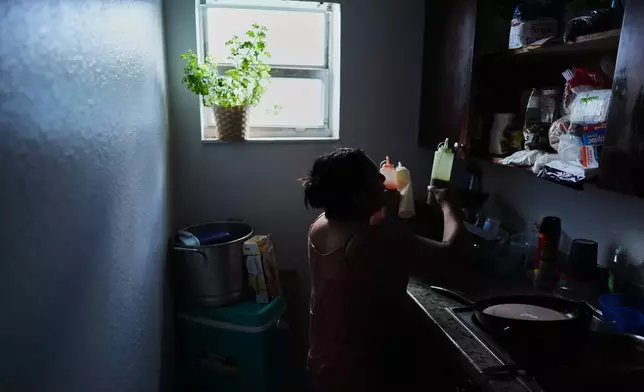

Today, breastfeeding and caring for two children, she wakes up at 3 a.m. to cook lunches she sells for $10 each.

She walks with her son in a stroller to take her daughter to school, then spends afternoons selling homemade ice cream and chocolate-covered bananas door to door with her two children.

Amavilia crossed the border in September 2023 and did not seek asylum or any type of legal status. She said her daughter grows anxious around police. She urges her to stay calm, smile and walk with confidence.

“I’m afraid to go out, but I always go out entrusting myself to God,” she said. “Every time I return home, I feel happy and grateful.”

Guatemalan migrant Amavilia, 31, gets out the sauces she uses to flavor the corn on the cob she sells, inside her South Florida apartment, Wednesday, Oct. 8, 2025, after her infant son's father, who worked in construction, was detained and deported to Guatemala. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

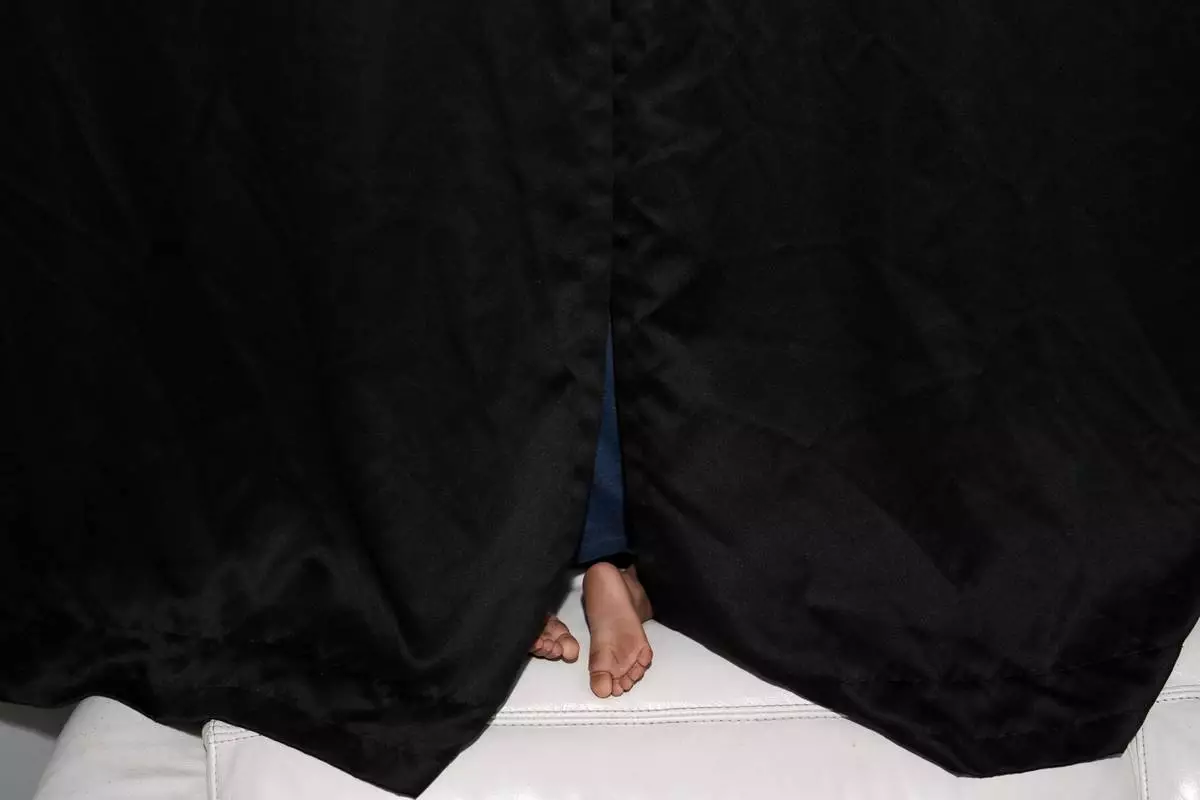

The two-year-old son of pregnant, asylum-seeker Yaoska peers out the window of the Miami-area motel room where he lives with his mother and brother, after their father was deported to Nicaragua, Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

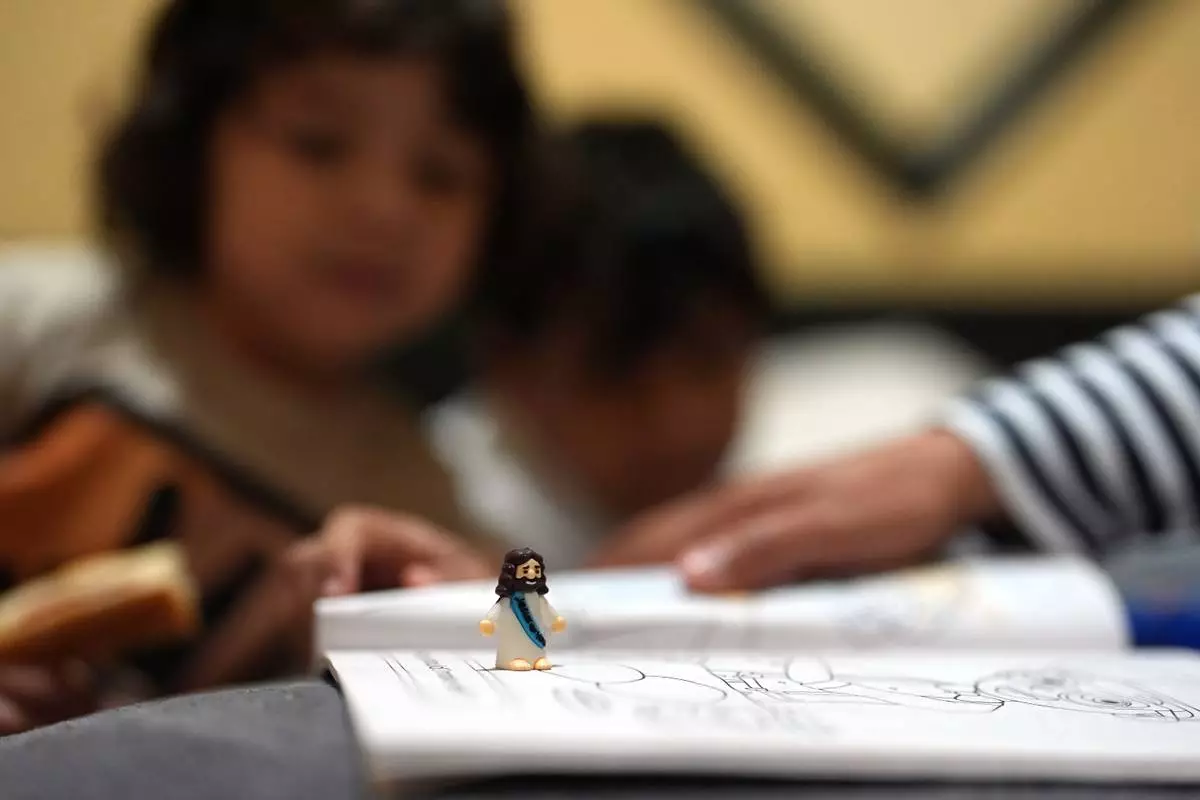

A miniature Jesus figurine sits on a coloring book inside the Miami-area motel room where Jakelin Pasedo is living with her two sons, who all have refugee status, Wednesday, Oct. 22, 2025, after their father requested to be sent back to Venezuela after months in immigration detention. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Diapers and clothes fill the shelves of the apartment in South Florida where Guatemalan migrant Amavilia, 31, front, lives with her two children and a roommate, after her partner Edgar was detained days after their son's birth and deported to Guatemala, Wednesday, Oct. 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

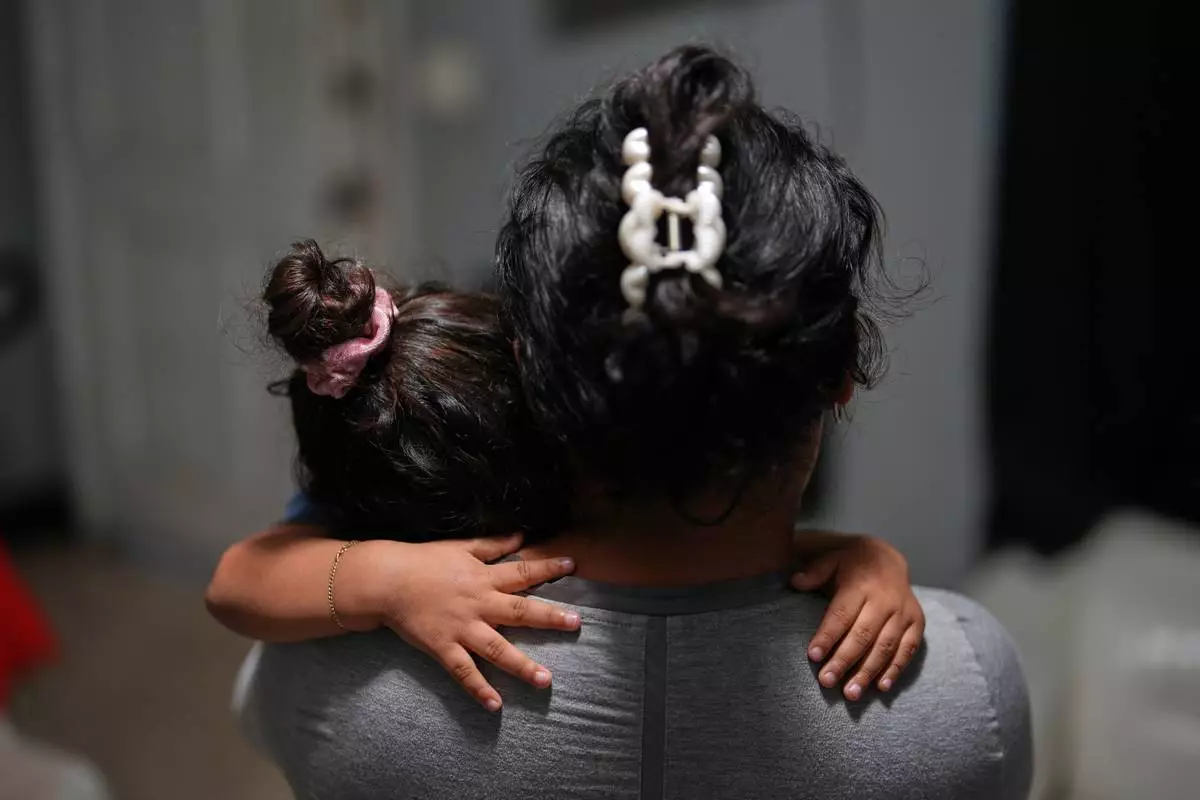

Jakelin Pasedo, 39, hugs her five-year-old son inside the Miami-area motel room where she lives with her two children, who all have refugee status, Wednesday, Oct. 22, 2025, after their father requested to be sent back to Venezuela after months in immigration detention. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

The two-year-old son of pregnant, asylum-seeker Yaoska hunts for a snack in the mini fridge of the Miami-area motel room where he lives with his mother and brother, after their father was deported to Nicaragua, Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Guatemalan migrant Amavilia, 31, holds her infant son, whose father Edgar was detained days after his birth and later deported to Guatemala, inside the South Florida apartment where she lives with her two children and a roommate, Wednesday, Oct. 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

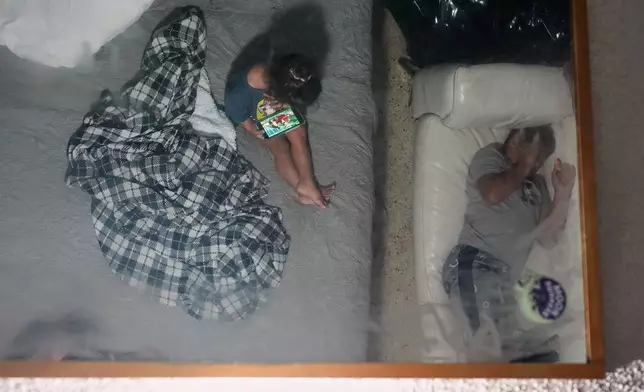

Two brothers are reflected in a ceiling mirror as they pass the time in the Miami-area motel room where they are living with their pregnant mother Yaoska after their father was deported to Nicaragua, Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Pregnant asylum-seeker Yaoska, 32, comforts her two-year-old son who was not feeling well, inside the Miami-area motel room where she and her children are living after her husband was deported to Nicaragua, Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)