HONG KONG (AP) — Hong Kong's biggest pro-democracy party voted Sunday to dissolve after more than 30 years of activism, marking the end of an era of the Chinese semiautonomous city 's once-diverse political landscape.

Democratic Party chairperson Lo Kin-hei said the political environment was “one important point” among the factors they considered, and about 97% of members' ballots were in support of its liquidation. He said it is the best way forward for its members.

Click to Gallery

Yeung Sum, committee member of Hong Kong's Democratic Party, at a press conference at the office of Hong Kong's Democratic Party in Hong Kong on Sunday, Dec. 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Lo Kin-hei, chairman of Hong Kong's Democratic Party, center, speaks at a press conference at the office of Hong Kong's Democratic Party in Hong Kong on Sunday, Dec. 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Lo Kin-hei, chairman of Hong Kong's Democratic Party, center, speaks at a press conference at the office of Hong Kong's Democratic Party in Hong Kong on Sunday, Dec. 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Lo Kin-hei, chairman of Hong Kong's Democratic Party, speaks at a press conference at the office of Hong Kong's Democratic Party in Hong Kong on Sunday, Dec. 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Lo Kin-hei, chairman of Hong Kong's Democratic Party, center, and other committees members pose for photographs at a press conference at the office of Hong Kong's Democratic Party in Hong Kong on Sunday, Dec. 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

FILE - Signage is displayed at the office of Hong Kong's Democratic Party in Hong Kong on Sunday, April 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei, File)

“Yet as the times have shifted, we now, with deep regret, must bring this chapter to a close,” he said.

Party veterans had earlier told The Associated Press that some members were warned of consequences if the party didn’t shut down.

Its demise reflects the dwindling freedoms promised to the former British colony when it returned to China’s rule in 1997.

China imposed a national security law in June 2020, following massive anti-government protests the year before, saying it was necessary for the city's stability. Under the law, many leading activists, including the Democratic Party's former chairs Albert Ho and Wu Chi-wai and other former lawmakers, were arrested.

Jimmy Lai, founder of the pro-democracy Apple Daily newspaper, was also charged under the law. Lai will hear his verdict on Monday. Apple Daily was one of the vocal independent outlets shut down over the past five years.

Dozens of civil society groups have also closed, including the second-largest pro-democracy party, Civic Party and a group that organized annual vigils commemorating the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown.

In June, the League of Social Democrats, which had remained active in holding tiny street protests in recent years, announced its closure, citing immense political pressure.

The Democratic Party, founded in 1994, was a moderate opposition party that pushed for universal suffrage in electing the city's leader for decades. Prominent party members include Martin Lee, nicknamed the city’s “father of democracy,” Ho, former leader of the group that organized Tiananmen vigils, and journalist-turned-activist Emily Lau.

It once held multiple legislative seats and amassed dozens of directly elected district councillors who helped residents with issues in their households and municipal matters. Some of its former members joined the government as senior officials.

Its willingness to negotiate with Beijing led to its proposal being included in a 2010 political reform package — a move that drew harsh criticism from some members and other democracy advocates who wanted more sweeping changes.

As new pro-democracy groups grew, the party’s influence declined. But when the 2019 protests swept Hong Kong, the party’s activism won widespread support again.

During Beijing's crackdown, the Democratic Party has turned into more like a pressure group. Electoral overhauls that were designed to ensure only “patriots” administer the city effectively shut out all pro-democracy politicians in the legislature and district councils.

The party pressed on by holding news conferences on livelihood issues. It even submitted opinions on a homegrown national security legislation before it was enacted in March 2024.

Earlier this year, the party decided to set up a task force to look into the procedures involved in dissolving itself, and its leadership secured members' mandate to move closer to this goal.

Former chairperson Yeung Sum in Sunday's news conference said the party's disbandment indicated the regression of Hong Kong from being a free and liberal society. He said the route to implementing democracy after the 1997 handover wasn’t a total failure, saying the city had just gone halfway through that path.

Yeung said if one day, there could be a review of the “one country, two systems” principle, which Beijing uses to govern Hong Kong, and it could move back toward being more open, the city would have a better future.

“Now, it's a low point, but we haven’t lost all hope," he said.

On whether Hong Kong will still have a democracy movement, Lo said it depends on every Hong Konger, highlighting that universal suffrage is promised under the city's mini-constitution.

“If Hong Kong people believe that democracy is the way to go, I believe that they will keep on striving for democracy."

Yeung Sum, committee member of Hong Kong's Democratic Party, at a press conference at the office of Hong Kong's Democratic Party in Hong Kong on Sunday, Dec. 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Lo Kin-hei, chairman of Hong Kong's Democratic Party, center, speaks at a press conference at the office of Hong Kong's Democratic Party in Hong Kong on Sunday, Dec. 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Lo Kin-hei, chairman of Hong Kong's Democratic Party, center, speaks at a press conference at the office of Hong Kong's Democratic Party in Hong Kong on Sunday, Dec. 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Lo Kin-hei, chairman of Hong Kong's Democratic Party, speaks at a press conference at the office of Hong Kong's Democratic Party in Hong Kong on Sunday, Dec. 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Lo Kin-hei, chairman of Hong Kong's Democratic Party, center, and other committees members pose for photographs at a press conference at the office of Hong Kong's Democratic Party in Hong Kong on Sunday, Dec. 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

FILE - Signage is displayed at the office of Hong Kong's Democratic Party in Hong Kong on Sunday, April 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei, File)

SANTIAGO, Chile (AP) — As Chileans vote on Sunday, even detractors of ultra-conservative former lawmaker José Antonio Kast say the candidate whose radical ideas lost him the past two elections is now almost certain to become Chile’s next leader.

Kast’s meaningful lead in the polls over his rival in the presidential runoff, communist Jeannette Jara, shows how the hard-liner agitating for mass deportations of immigrants has seized the mantle of the traditional right in a country that once defined its post-dictatorship democratic revival with a vow to contain such political forces.

But much is also up for grabs about Chile’s political direction.

Kast's claim to a popular mandate depends on his margin of victory on Sunday over Jara, the center-left governing party candidate who narrowly beat him in the first round of elections last month.

Although various right-wing parties won around 70% of the vote in that election, substantial support for a populist center-right candidate who described himself as an alternative to Kast’s “fascism” revealed that, between the contrasting ideologies of the front-runners, sit hundreds of thousands of centrist voters with no real representation.

“Both are too extreme for me,” said Juan Carlos Pileo, 44, who plans to cast a blank ballot Sunday, as voting is now mandatory in Chile’s elections. “I can’t trust someone who says she’s a communist to be moderate. And I can’t trust someone who exaggerates the amount of crime we have in this country and blames immigrants to be fair and respectful.”

It remains a question whether Kast, an admirer of U.S. President Donald Trump, can implement his more grandiose promises.

They include slashing $6 billion in public spending over just 18 months without eliminating social benefits, deporting over 300,000 immigrants in Chile with no legal status and expanding the powers of the army to fight organized crime in a country still haunted by Gen. Augusto Pinochet’sbloody military dictatorship from 1973 to 1990.

For one, Kast’s far-right Republican Party lacks a majority in Congress, meaning that he’ll need to negotiate with moderate right-wing forces that could bristle at those proposals, significantly shaping policy and his own legacy.

Political compromises could temper Kast’s radicalism, but also jeopardize his position with voters who expect him to deliver quickly on his law-and-order campaign promises.

At each campaign event, Kast has taken to ticking off the number of days remaining until Chile's March 11 presidential inauguration, warning they should get out before they'll "have to leave with just the clothes on their backs.”

Jorge Rubio, 63, a Chilean banker in downtown Santiago, the capital, said he's “also counting down the days.”

“That’s why we’re voting for Kast," he said.

As the pandemic shuttered borders, transnational criminal organizations like Tren de Aragua seized illegal migration routes to gain a foothold in Chile, long considered among Latin America's safest countries. Homicides hit a record high in 2022, the first year of President Gabriel Boric’s tenure.

Kast insists that Boric’s government is too soft on immigration and crime, which the far-right leader argues are connected although the data does not necessarily support his narrative. Boric’s approval rating has plummeted, standing now at just 30%.

Yet many say the firebrand former student protester who came to power in 2021 pledging to transform Chile's market-led economy, has risen to the occasion. Boric went from criticizing the use of police force on the campaign trial to pouring money into the security forces. He sent the military to reinforce Chile's northern border, stiffened penalties for organized crime and created the country's first public security ministry.

Chile's homicide rate is now falling, about on par with the rate in the United States. That has done nothing to change Chileans' feelings of profound insecurity.

In Libya, where fractious militias jostle for political power, over 70% of people feel safe walking alone at night, according to a recent Gallup survey of 144 countries.

In Chile, just 39% of people do, around the same as in Ecuador, which is now in the midst of a violent, drug-driven crime wave.

As Boric's former minister of labor, Jara became popular for passing some of the administration's most important welfare measures.

That matters little now. Voters' concerns have forced her to switch gears. She has vowed to toughen border security, register undocumented migrants, tackle money laundering and step up police raids.

But promises to restore law and order are more persuasive coming from an insurgent outsider who has made security a key part of his agenda for years.

“Kast has been smart and strategic in focusing on migration and security," said Lucía Dammert, a sociologist and Boric’s first chief of staff. “It has been very difficult for the Jara campaign to move him away from those issues.”

Learning from his previous two failed presidential runs, Kast has avoided topics that fire up his critics — such as his German-born father’s Nazi past, his nostalgia for Pinochet's dictatorship and his opposition to same-sex marriage and abortion.

When asked, Kast says only that his values remain the same. His supporters, including voters who previously spurned him over his social conservatism, now say that abstract human rights concerns come after their need for safety on the streets.

“It's not very nice to hear that he's going to separate immigrant children from their parents, it's sad, that's going to be a problem for me,” said Natacha Feliz, a 27-year-old immigrant from the Dominican Republic referring to a recent interview in which Kast said immigrant parents without legal status who didn’t self-deport would be obliged to hand their kids over to the state.

“But this is happening everywhere, not just in Chile. Let's just hope that our security situation improves."

Associated Press writer Nayara Batschke in Santiago, Chile, contributed to this report.

A voter casts his ballot during the presidential runoff election in Santiago, Chile, Sunday, Dec. 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Esteban Felix)

Luis Soto prepares to vote in the presidential runoff election in Santiago, Chile, Sunday, Dec. 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko)

Richard Ferreira, a Venezuelan residing in Chile, waits for polls to open during the presidential runoff election in Santiago, Sunday, Dec. 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko)

Police guard the Mapocho station polling station during the presidential runoff election in Santiago, Chile, Sunday, Dec. 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko)

Presidential candidate Jeannette Jara of the Unidad por Chile coalition addresses supporters during a rally ahead of the presidential runoff election in Santiago, Chile, Wednesday, Dec. 10, 2025. (AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko)

A man cycles past campaign ads for presidential candidate Jose Antonio Kast and Argentina's President Javier Milei reading in Spanish "Our future is in danger" ahead of the presidential runoff election in Santiago, Chile, Friday, Dec. 12, 2025. (AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko)

Presidential candidate Jose Antonio Kast of the Republican Party addresses supporters, from behind a protective glass panel, during a rally ahead of the runoff election in Temuco, Chile, Thursday, Dec. 11, 2025. (AP Photo/Esteban Felix)

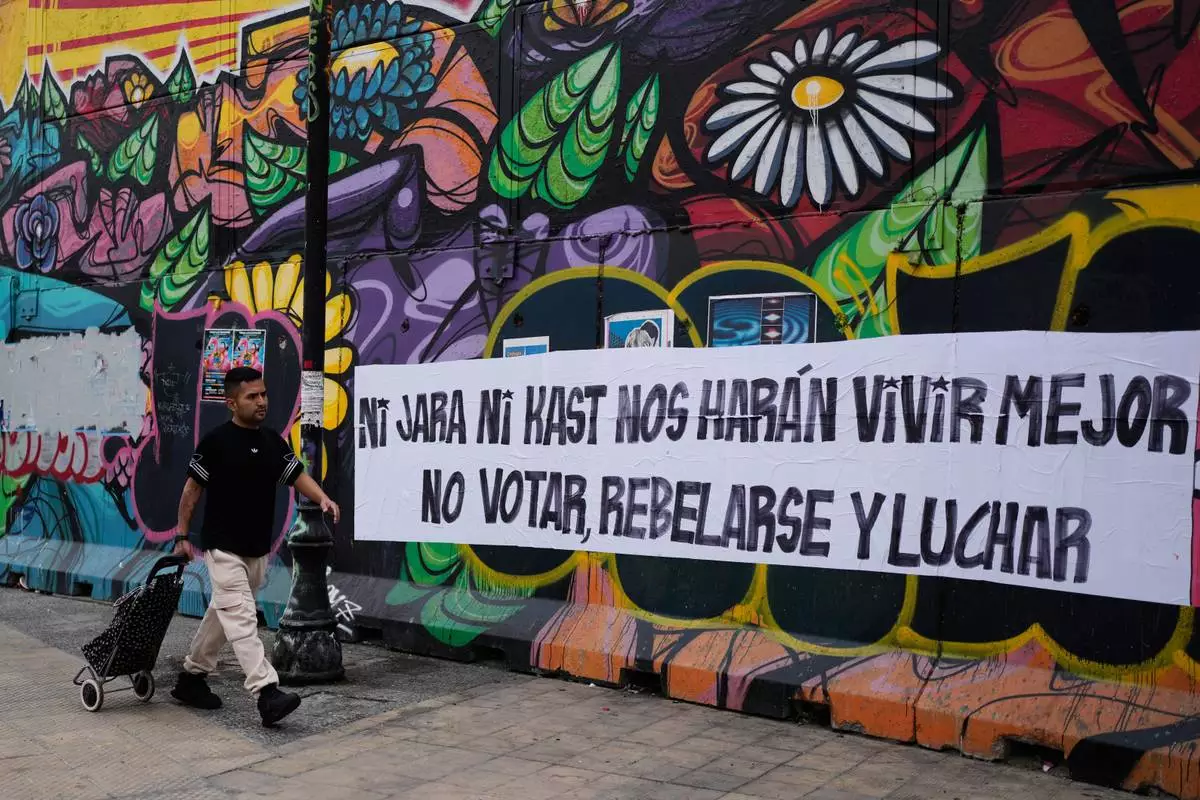

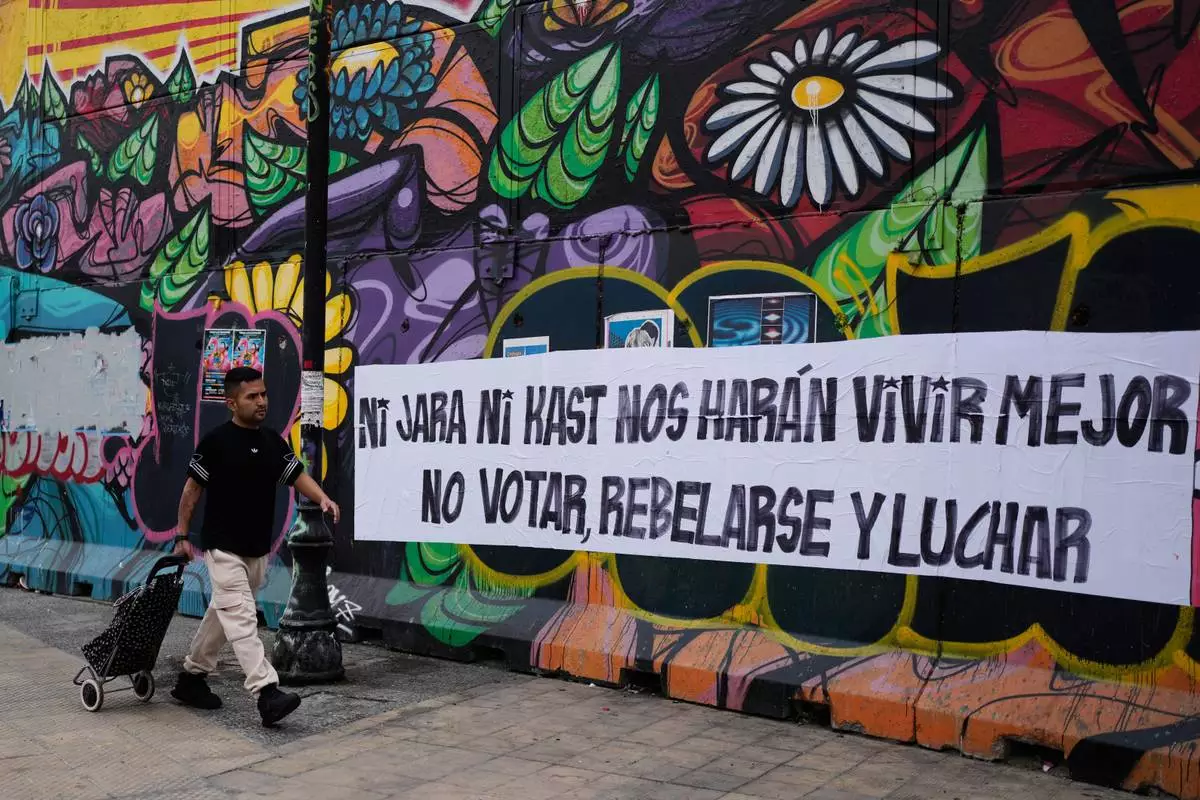

A campaign banner reads in Spanish "Neither Jara nor Kast will make our lives better, don't vote, rebel and fight" ahead of the presidential runoff election in Santiago, Chile, Friday, Dec. 12, 2025. (AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko)

Presidential candidates Jose Antonio Kast of the Republican Party and Jeannette Jara of the Unity for Chile coalition shake hands during a debate ahead of runoff elections in Santiago, Chile, Tuesday, Dec. 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Esteban Felix)