LEXINGTON, Neb. (AP) — A small town in rural Nebraska is losing its biggest employer, a Tyson Foods' beef plant, which will be laying off 3,200 workers next month in a town of around 11,000 people.

Lexington, Nebraska, is expected to lose hundreds of families who will be forced to move away in search of other work. The exodus will likely cause spinoff layoffs in the town's shops, restaurants and schools.

The impact on the town and workers will be “close to the poster child for hard times,” said Michael Hicks, director of the Center for Business and Economic Research at Indiana’s Ball State University.

All told, the job losses are expected to reach 7,000, largely in Lexington and surrounding counties, according to estimates from the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, and shared with The Associated Press. Tyson employees alone will lose an estimated $241 million in pay and benefits annually.

It threatens to unravel a town where the American Dream was still attainable, where immigrants who didn’t speak English and never graduated high school bought homes, raised children in a safe community and sent them to college.

Tyson says it’s closing the plant to “right-size” its beef business after a historically low cattle herd in the U.S. and the company’s expected loss of $600 million on beef production next fiscal year.

Tyson workers, business owners and town leaders spoke to The Associated Press for a report on the plant’s closure.

Here are some takeaways.

Lexington sits near the dead center of the United States, surrounded by fields of corn, grain silos and cattle.

The plant opened in 1990 and was bought by Tyson a decade later, attracting thousands of workers who labor on cleaning crews and forklifts, on the slaughter floor and trimming cuts of meat.

The town nearly doubled in population and flourished with leafy neighborhoods, recreation centers, a one-screen movie theater and a good school system. Nearly half the students in Lexington have a parent who works at the Tyson plant, school officials estimated.

Many Tyson workers have lived in Lexington for decades, building community at the plant and in the town's many churches, including Francisco Antonio.

The 52-year-old father of four said he’ll stay a few months in Lexington and look for work, though “now there’s no future.” He took off his glasses, paused, apologized and tried to explain his emotions.

“It’s home mostly, not the job,” he said, replacing his glasses with an embarrassed smile.

Thousands of Tyson workers have mortgages, car and insurance payments, property taxes or tuition costs that they won’t have an income to pay.

For many, finding another job isn't easy, particularly older workers who don’t speak English, haven’t graduated high school and aren’t computer savvy. The last application some filled out was decades ago.

“We know only working in meat for Tyson, we don’t have any other experience,” said Arab Adan. The Kenyan immigrant sat in his car with his two energetic sons, who asked him a question he has no answer to: “Which state are we gonna go, daddy?”

“They only want young people now,” said Juventino Castro, who’s worked at Tyson for a quarter-century. “I don’t know what’s going to happen in the time I have left.”

Lupe Ceja has saved a little money, but it won’t last long. Luz Alvidrez has a cleaning gig that will sustain her for awhile. Others might return to Mexico for a time. Nobody has a clear plan.

“It won’t be easy,” said Fernando Sanchez, a Tyson worker for 35 years who sat with his wife. “We started here from scratch and it’s time to start from scratch again.”

Tears rolled down his wife’s cheeks and he squeezed her hand.

The domino effect could go something like this: If 1,000 families leave town, said economist Hicks — who wouldn’t be surprised if it were double that — seats would be left empty in schools, leading to teacher layoffs; there would be far fewer customers in restaurants, shops and other businesses.

Most of the customers at Los Jalapenos, a Mexican restaurant down the street from the plant, are Tyson workers. They fill booths after work and are greeted by owner Armando Martinez’s mustachioed grin and bellow of “Hola, amigo!”

If he can’t keep up with bills, the restaurant will close, said Martinez, who undergoes dialysis for diabetes and has an amputated foot.

“There’s just nowhere we can go,” he said.

Many, including City Manager Joe Pepplitsch, are hoping Tyson puts the plant up for sale and a new company comes in bringing new jobs. That isn’t a quick fix, requiring time, negotiations, renovations and no guarantee of comparable jobs.

Pepplitsch, who noted that Tyson hasn't had to pay city taxes due to a deal negotiated years ago, said that “Tyson owes this community a debt. I think they have a responsibility here to help ease some of the impact."

Asked by the AP for comment about plans for the site, Tyson said in a statement that it “is currently assessing how we can repurpose the facility within our own production network.” It did not provide details or say whether it plans to offer support to the community through the plant closure.

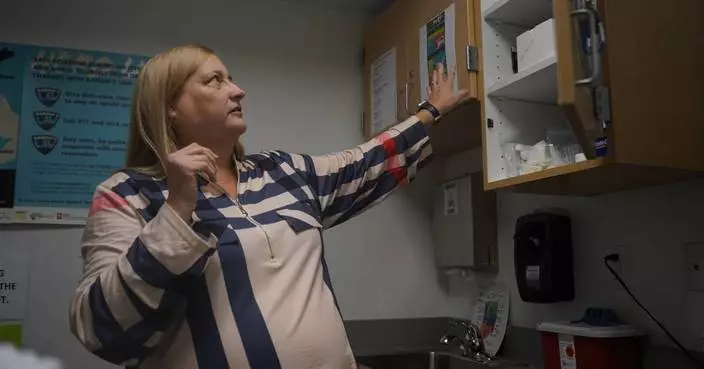

Two women listen during an informational meeting held by the Nebraska Department of Labor for Tyson Foods employees in Lexington, Neb., Thursday, Dec. 4, 2025. (AP Photo/Thomas Peipert)

A worker walks through steam coming from the Tyson Foods' beef plant in Lexington, Neb., Thursday, Dec. 4, 2025. (AP Photo/Thomas Peipert)

Trucks carrying grain drive past cattle in pens at the Darr Feedlot in Cozad, Neb., Friday, Dec. 5, 2025. (AP Photo/Thomas Peipert)

Drivers wait in line at a mobile food bank organized by Crossroads Mission Avenue near the Tyson Foods' beef plant in Lexington, Neb., Thursday, Dec. 4, 2025. (AP Photo/Thomas Peipert)

Two men walk past a business in downtown Lexington, Neb., Saturday, Dec. 6, 2025. (AP Photo/Thomas Peipert)