NEW YORK (AP) — Sports were turned upside down 50 years ago Tuesday by a man who never threw or kicked a ball.

A lawyer with expertise in labor relations struck down Major League Baseball's reserve clause, which had bound players to their teams since the 1870s.

No one could have predicted then that the 65-page decision issued Dec. 23, 1975, by arbitrator Peter Seitz — who later compared baseball owners to “the French barons of the 12th century” — would lead to an upheaval that made thousands of players multimillionaires.

“The real floodgates opened after that,” former pitcher David Cone said. “Players were finally in all walks of life, in all sports, were finally able to see what, hey, what free agency really looks like. There was all the doom and gloom back then from one side that said: 'This is going to ruin the game. It’s not sustainable.' And actually, it was just the opposite. It made the game better."

Baseball's average salary was $44,676 at the time of the decision and climbed to about $5 million this year, a 112-fold increase. Outfielder Juan Soto commanded a record $765 million deal with the New York Mets last December.

Showing how much players’ earning power was unleashed, that 1975 average would be $260,909 in current dollars, according to the Consumer Price Index.

Seitz's decision was followed by free agency upheavals in the NFL, NBA, NFL and European soccer.

“The timeframes largely align to suggest that there were indeed synergies between what was happening on the baseball side and what was happening in other sports,” current baseball players' association head Tony Clark said.

Curt Flood had lost a lawsuit arguing for free agency in 1972 when the U.S. Supreme Court upheld baseball’s antitrust exemption, ruling it was up to Congress to make any change.

In December 1974, Catfish Hunter was set free on a technicality when Seitz concluded Oakland Athletics owner Charlie Finley failed to make a $50,000 payment into a long-term annuity fund as specified in the pitcher's contract. Following a bidding war, Hunter signed a five-year contract with the New York Yankees for about $3.2 million.

“We saw this huge contract, it was like reading from another world,” recalled former All-Star pitcher Steve Rogers, among the first beneficiaries of free agency and later a long-time union official. “The magnitude was just unheard of, the number of dollars that were guaranteed to him. It didn’t take long for us to see that there was a lot of money to be spent in buying talent and then we started seeing: My talent is worth a lot."

Union head Marvin Miller and general counsel Dick Moss had in 1970 negotiated the first provision for grievances to be decided by an outside arbitrator, and they wanted a case to test the provision in each contract that gave the team the right to renew it for an additional year in perpetuity.

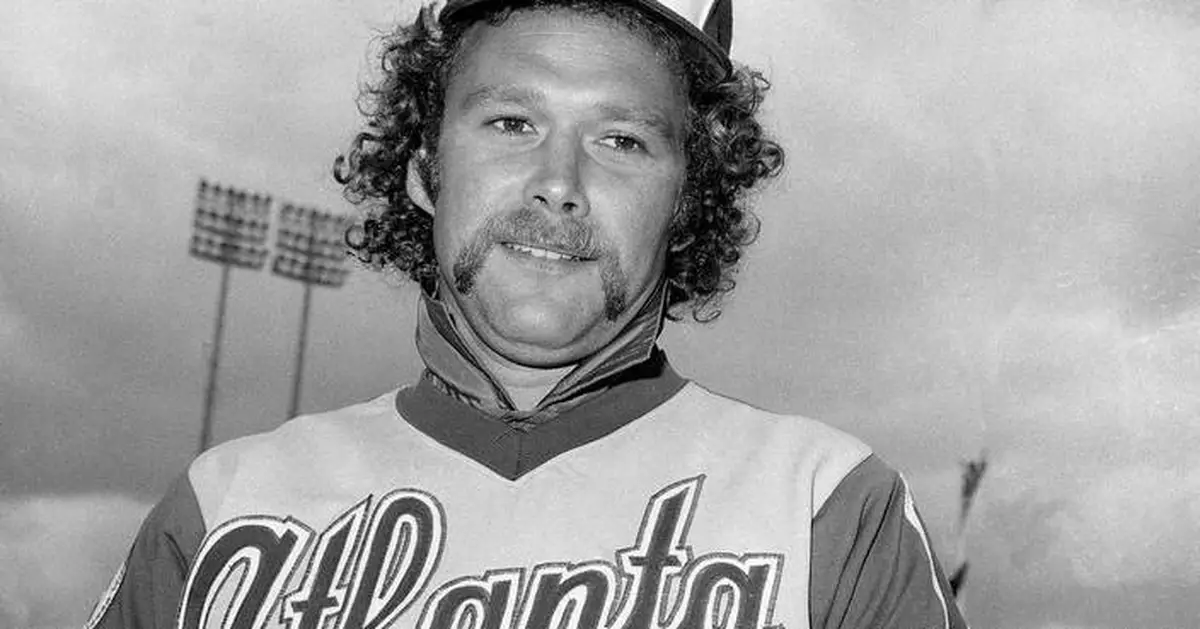

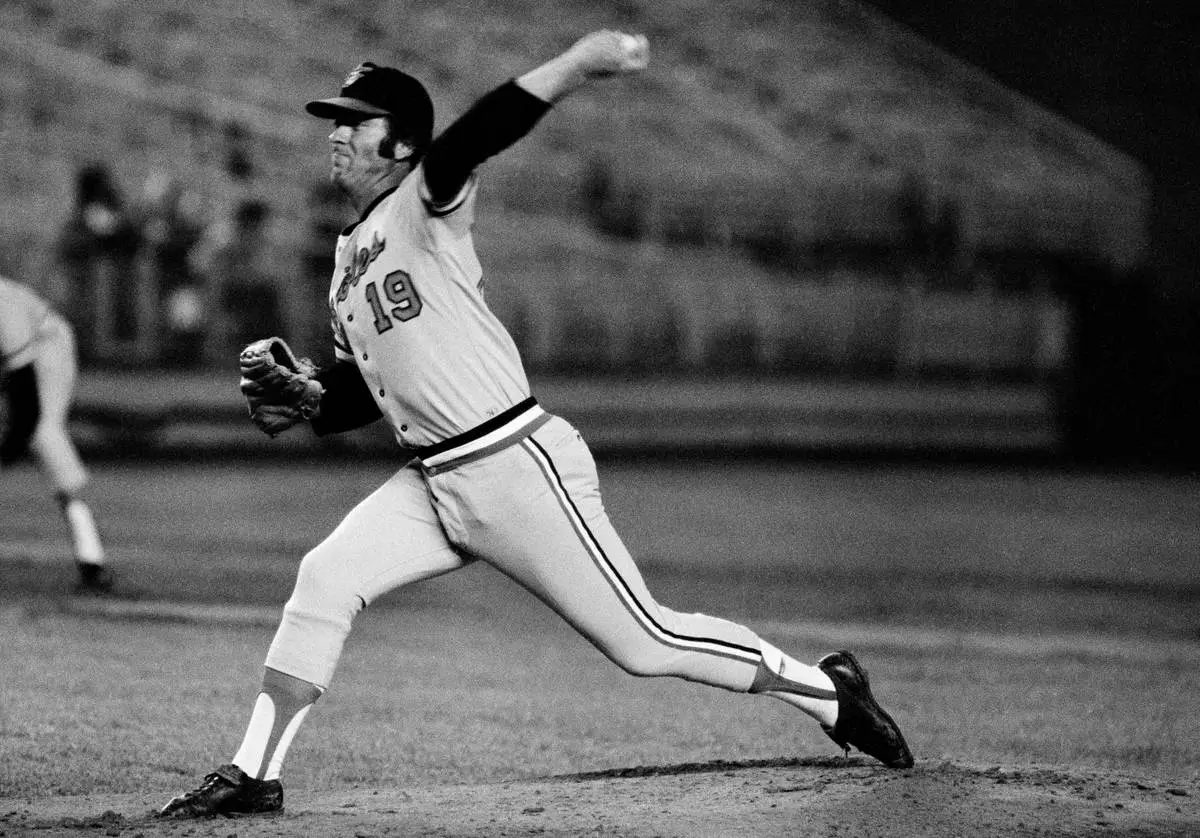

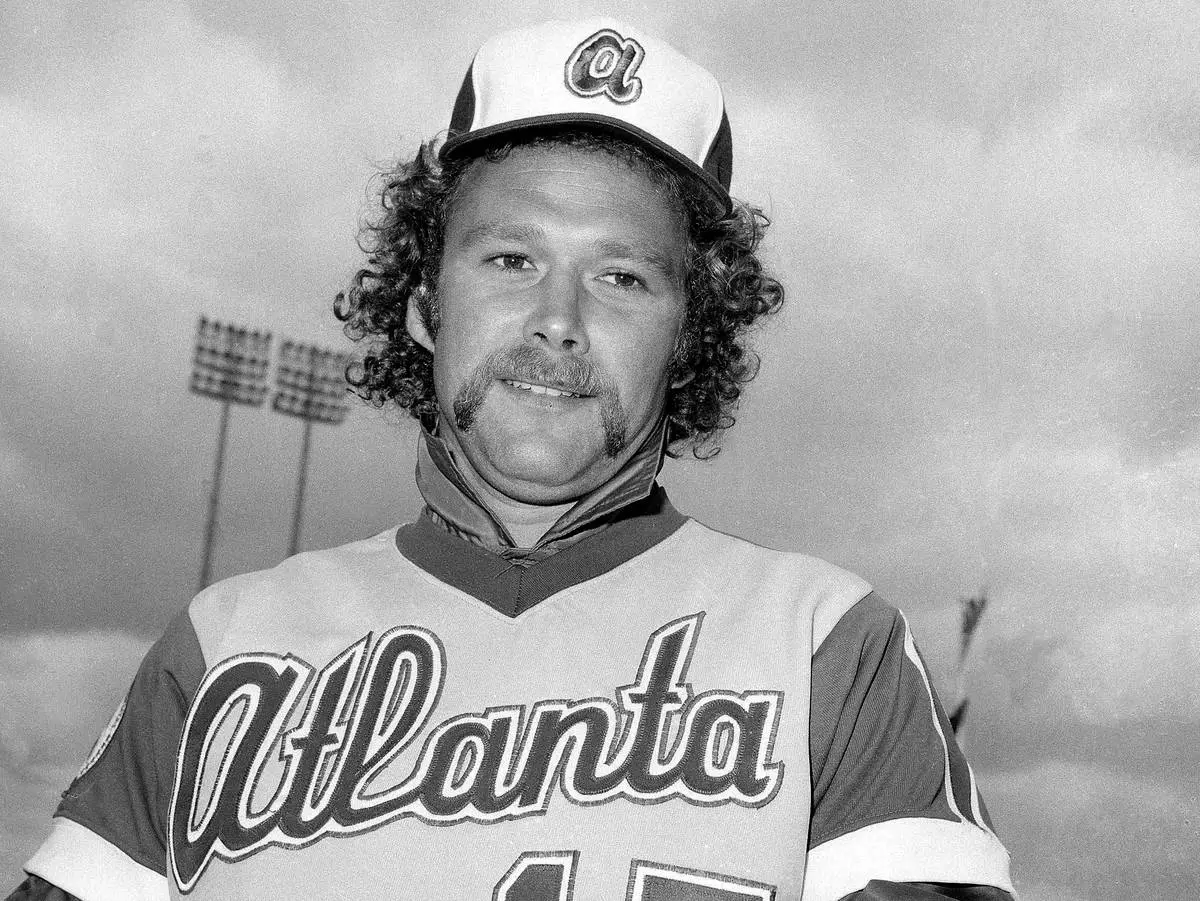

Language in each player agreement stated the club could "renew this contract for the period of one year on the same terms,″ except that the salary could be cut by as much as 20%. After playing the 1975 season under renewals, Andy Messersmith of the Los Angeles Dodgers and Dave McNally of the Montreal Expos maintained in a grievance the renewal period was one year only and they should be declared free.

Following a three-day hearing that generated an 842-page transcript and 97 exhibits, Seitz urged owners to settle the case as late as Dec. 9. Then-commissioner Bowie Kuhn urged owners to fire Seitz before a decision, but management’s Player Relations Committee refused because it was afraid of bad publicity.

“I predicted the decision,″ Kuhn told The Associated Press. ”I was not surprised. I had people examine his record. I thought there was a tilt to the players’ side.″

Seitz ruled for the union.

“This decision strikes no blow emancipating players from claimed serfdom or involuntary servitude such as was alleged in the Flood Case," Seitz wrote. “It does not condemn the reserve system presently in force on constitutional or moral grounds. It does not counsel or require that the system be changed to suit the predilections or preferences of an arbitrator acting as a philosopher-king intent upon imposing his own personal brand of industrial justice on the parties. It does no more than seek to interpret and apply provisions that are in the agreements of the parties.”

Management fired Seitz that afternoon and vowed to overturn the decision in federal court.

“Their basic attitude was, ’We are not going to change one comma of the reserve system — we like it the way it is,‴ Miller told the AP in 2000, a dozen years before his death. ”They can say on a stack of Bibles that they should have changed something. But their basic mindset was, ‘This is the way it is.’ They thought they could never lose in court. That servitude had existed for decades and decades and decades.″

Seitz’s decision was upheld in February 1976 by U.S. District Judge John W. Oliver and affirmed the following month by an 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals panel of Judges Floyd Robert Gibson, Gerald Heaney and Roy Laverne Stephenson.

That July 12, players and owners agreed to a four-year collective bargaining agreement creating one-time free agency for all players after 1976 or 1977 and going forward after six seasons of major league service, which is still in place. Future Hall of Famers Reggie Jackson and Rollie Fingers were among the first players to gain free-agent riches.

“The difference between winning and losing was billions and billions of dollars, maybe tens of billions of dollars,″ Moss, who died last year, said after holding a 25th anniversary party in 2020.

Seitz died in 1983.

Baseball has endured nine work stoppages since 1972 and another is possible when the current labor contract expires at the end of Dec. 1 next year.

"I think one can make a case that we’ve spent the last two-plus decades trying to re-establish some reasonable equilibrium,″ then-commissioner Bud Selig said in 2000.

AP MLB: https://apnews.com/hub/mlb

FILE - Baltimore Orioles Dave McNally delivers a pitch in the first inning of a baseball game against the New York Yankees at Shea Stadium in New York, May 24, 1974. (AP Photo/File)

FILE - Abritrator Peter Seitz speaks during a news conference after he gave free agent status to pitchers Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally by voiding the reserve clause in their contracts, Dec. 23, 1975, in New York. (AP Photo/File)

FILE - Atlanta Braves pitcher Andy Messersmith poses, April 1976. (AP Photo/File)