HOUSTON (AP) — Former Uvalde, Texas, schools police Officer Adrian Gonzales was among the first officers to arrive at Robb Elementary after a gunman opened fire on students and teachers.

Prosecutors allege that instead of rushing in to confront the shooter, Gonzales failed to take action to protect students. Many families of the 19 fourth-grade students and two teachers who were killed believe that if Gonzales and the nearly 400 officers who responded had confronted the gunman sooner instead of waiting more than an hour, lives might have been saved.

Click to Gallery

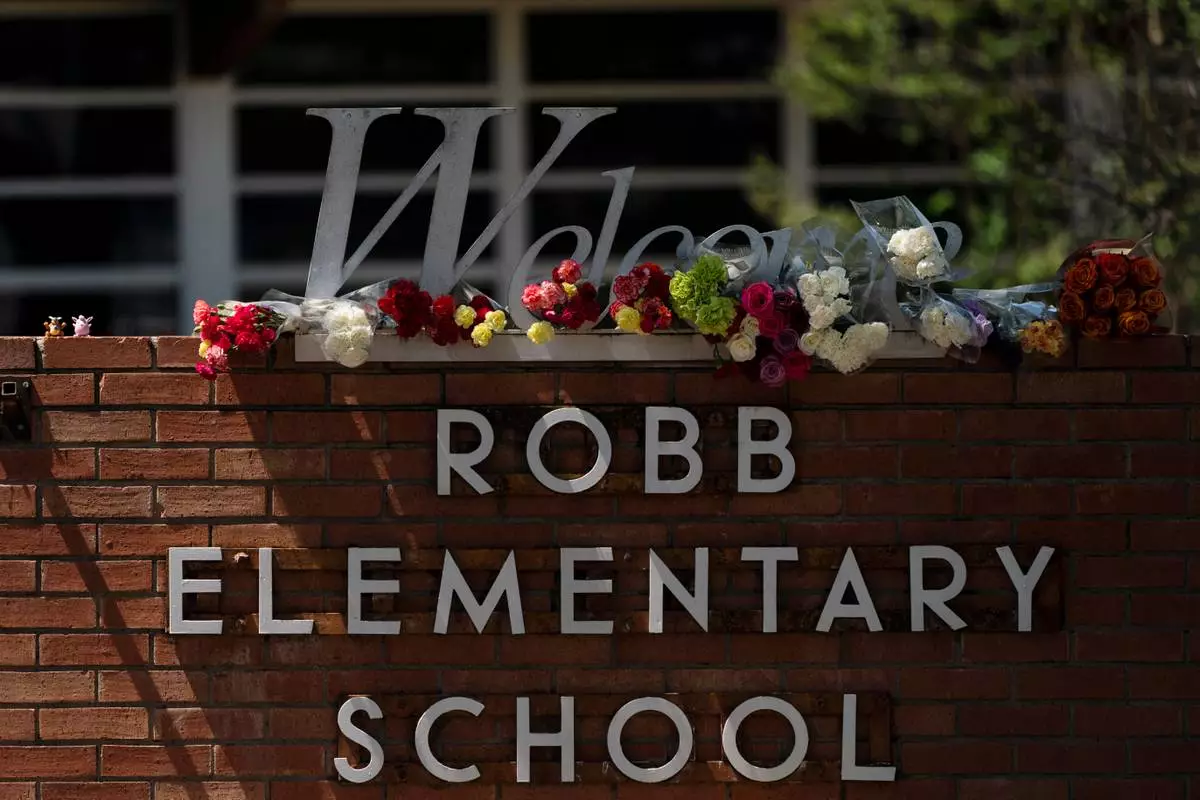

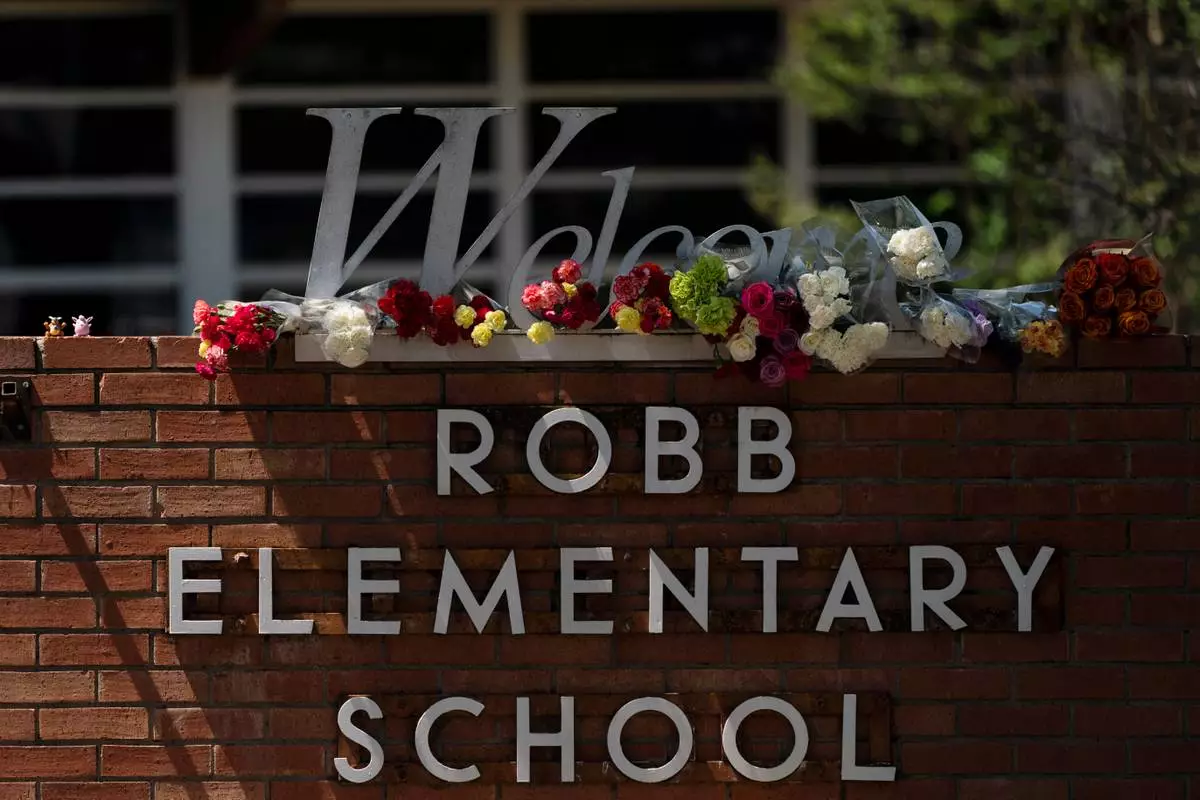

FILE - Flowers are placed around a welcome sign outside Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, May 25, 2022, to honor the victims killed in a shooting at the school. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong, File)

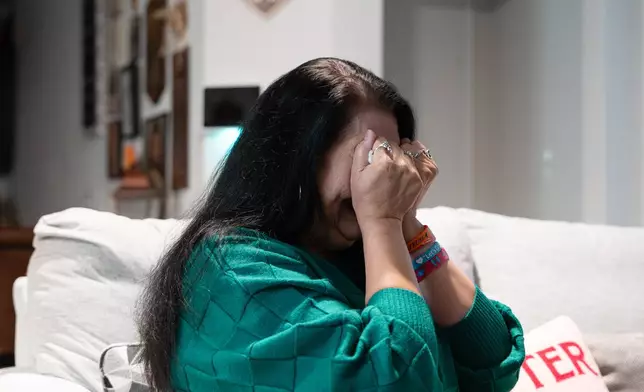

Velma Lisa Duran, sister of Robb Elementary teacher Irma Garcia, cries as she reflects on the 2022 Uvalde, Texas, school shooting during an interview on Dec. 19, 2025, in San Antonio. (AP Photo/Kin Man Hui)

Velma Lisa Duran, sister of Robb Elementary teacher Irma Garcia, poses with photos of her sister and brother-in-law, Joe Garcia, as she reflects on the 2022 Uvalde, Texas, school shooting on Dec. 19, 2025, in San Antonio. (AP Photo/Kin Man Hui)

FILE - This booking image provided by the Uvalde County, Texas, Sheriff's Office shows Adrian Gonzales, a former police officer for schools in Uvalde, Texas. (Uvalde County Sheriff's Office via AP, File)

FILE - Crosses with the names of shooting victims are placed outside Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, May 26, 2022. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong, File)

More than 3½ years since the killings, the first criminal trial over the delayed law enforcement response to one of the deadliest school shootings in U.S. history is set to begin.

It’s a rare case in which a police officer could be convicted for allegedly failing to act to stop a crime and protect lives.

Here’s a look at the charges and the legal issues surrounding the trial.

Gonzales was charged with 29 counts of child endangerment for those killed and injured in the May 2022 shooting. The indictment alleges he placed children in “imminent danger” of injury or death by failing to engage, distract or delay the shooter and by not following his active shooter training. The indictment says he did not advance toward the gunfire despite hearing shots and being told where the shooter was located.

Each child endangerment count carries a potential sentence of up to two years in prison.

State and federal reviews of the shooting cited cascading problems in law enforcement training, communication, leadership and technology and questioned why officers from multiple agencies waited so long before confronting and killing the gunman, Salvador Ramos.

Gonzales’ attorney, Nico LaHood, said his client is innocent and public anger over the shooting is being misdirected.

“He was focused on getting children out of that building,” LaHood, said. “He knows where his heart was and what he tried to do for those children.”

Jury selection in Gonzales’ trial is scheduled to begin Jan. 5 in Corpus Christi, about 200 miles (320 kilometers) southeast of Uvalde. The trial was moved after defense attorneys argued Gonzales could not receive a fair trial in Uvalde.

Gonzales, 52, and former Uvalde schools police chief Pete Arredondo are the only officers charged. Arredondo was charged with multiple counts of child endangerment and abandonment. His trial has not been scheduled, and he is also seeking a change of venue.

Prosecutors have not explained why only Gonzales and Arredondo were charged. Uvalde County District Attorney Christina Mitchell did not respond to a request for comment.

It’s “extremely unusual” for an officer to stand trial for not taking an action, said Sandra Guerra Thompson, a University of Houston Law Center professor.

“At the end of the day, you’re talking about convicting someone for failing to act and that’s always a challenge,” Thompson said, “because you have to show that they failed to take reasonable steps.”

Phil Stinson, a criminal justice professor at Bowling Green State University who maintains a nationwide database of roughly 25,000 cases of police officers arrested since 2005, said a preliminary search found only two similar prosecutions.

One involved a Florida sheriff’s deputy, Scot Peterson, who was charged after the 2018 Parkland school massacre for allegedly failing to confront the shooter — the first such prosecution in the U.S. for an on-campus shooting. He was acquitted by a jury in 2023.

The other was the 2022 conviction of former Baltimore police officer Christopher Nguyen for failing to protect an assault victim. The Maryland Supreme Court overturned that conviction in July, ruling prosecutors had not shown Nguyen had a legal duty to protect the victim.

The justices in Maryland cited a prior U.S. Supreme Court decision on the public duty doctrine, which holds that government officials like police generally owe a duty to the public at large rather than to specific individuals unless a special relationship exists.

Michael Wynne, a Houston criminal defense attorney and former prosecutor not involved in the case, said securing a conviction will be difficult.

“This is clearly gross negligence. I think it’s going to be difficult to prove some type of criminal malintent,” Wynne said.

But Thompson, the law professor, said prosecutors may nonetheless be well positioned.

“You’re talking about little children who are being slaughtered and a very long delay by a lot of officers,” she said. “I just feel like this is a different situation because of the tremendous harm that was done to so many children.”

Associated Press writer Jim Vertuno in Austin, Texas, contributed.

Follow Juan A. Lozano: https://x.com/juanlozano70

FILE - Flowers are placed around a welcome sign outside Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, May 25, 2022, to honor the victims killed in a shooting at the school. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong, File)

Velma Lisa Duran, sister of Robb Elementary teacher Irma Garcia, cries as she reflects on the 2022 Uvalde, Texas, school shooting during an interview on Dec. 19, 2025, in San Antonio. (AP Photo/Kin Man Hui)

Velma Lisa Duran, sister of Robb Elementary teacher Irma Garcia, poses with photos of her sister and brother-in-law, Joe Garcia, as she reflects on the 2022 Uvalde, Texas, school shooting on Dec. 19, 2025, in San Antonio. (AP Photo/Kin Man Hui)

FILE - This booking image provided by the Uvalde County, Texas, Sheriff's Office shows Adrian Gonzales, a former police officer for schools in Uvalde, Texas. (Uvalde County Sheriff's Office via AP, File)

FILE - Crosses with the names of shooting victims are placed outside Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, May 26, 2022. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong, File)

Families who lost loved ones in the 2022 attack on an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas, have sought for nearly four years to hold accountable the police who waited more than an hour to confront the shooter while children and teachers lay dead or wounded in classrooms.

Now one of the first officers on the scene is about to stand trial on multiple charges of child abandonment and endangerment. Former Uvalde schools police officer Adrian Gonzales is accused of ignoring his training in a crisis with deadly consequences. His attorney insists he was focused on helping children escape from the building.

The trial that starts Monday offers potentially one of the last chances to see police answer for the long delay. The families have pinned their hopes on the jury after their gun-control efforts were rejected by lawmakers, and their lawsuits remain unresolved. A few parents ran for political office to seek change, with mixed results.

The proceedings will provide a rare example of an officer being criminally charged with not doing more to stop a crime and protect lives.

Jesse Rizo's niece was one of 19 children and two teachers killed by the teenage gunman in one of the deadliest school shootings in U.S. history. Nine-year-old Jackie Cazares still had a pulse when rescuers finally reached her, Rizo said.

“It really bothers us a lot that maybe she could have lived,” he said.

Only two of the 376 officers from local, state and federal agencies on the scene have been charged — a fact that haunts Velma Lisa Duran, whose sister, Irma Garcia, was one of the teachers gunned down.

"What about the other 374?" Duran asked through tears. "They all waited and allowed children and teachers to die.”

The charges reflect the dead and wounded children, but not her sister's death or that of the other teacher who was killed.

“Where is the justice in that?” Duran asked. “Did she not exist?”

Prosecutors will likely face a high bar to win a conviction. Juries are often reluctant to convict law enforcement officers for inaction, as seen after the Parkland, Florida, school massacre in 2018.

Sheriff’s deputy Scot Peterson was charged with failing to confront the shooter in that attack. It was the first such prosecution in the U.S. for an on-campus shooting, and Peterson was acquitted by a jury in 2023.

Police and Texas Gov. Greg Abbott initially said swift law enforcement action killed Uvalde gunman Salvador Ramos and saved lives. But that version quickly unraveled as families described begging police to go into the building and 911 calls emerged from students pleading for help.

The reality was that 77 minutes passed from the time officers first arrived until a tactical team breached the classroom and killed Ramos.

Multiple reports from state and federal officials cataloged cascading problems in law enforcement training, communication, leadership and technology, and they questioned whether officers prioritized their own lives over those of the children and teachers.

Gonzales was charged two years later in an indictment that alleged he placed children in “imminent danger” of injury or death by failing to engage, distract or delay the gunman and by not following his active shooter training.

The indictment said he did not advance toward the gunfire despite hearing shots and being told where the shooter was.

The only other officer to be charged is former Uvalde schools Police Chief Pete Arredondo. His trial on similar charges has not yet been set.

Uvalde County District Attorney Christina Mitchell did not respond to requests from The Associated Press for comment on the indictments or whether a grand jury considered charging other officers.

According to a report by state lawmakers, Gonzales was among the first officers in the building. They heard gunfire and retreated without firing a shot after Ramos shot at them.

Gonzales told investigators he later helped break windows to remove students from other classrooms.

“He was focused on getting children out of that building,” said Gonzales' attorney, Nico LaHood, a former district attorney and prosecutor in San Antonio. “He knows where his heart was and what he tried to do for those children.”

The trial was moved from Uvalde to Corpus Christi, 200 miles away, after defense attorneys and prosecutors agreed a change of venue would be the best way to find an impartial jury.

In Uvalde, a city of about 15,000 people, the Robb Elementary building is still standing, but it's empty. A memorial of 21 white crosses and flowers sits in front of the school sign. Another memorial is displayed at a downtown water fountain plaza. Murals of the victims cover walls on buildings around town.

Craig Garnett, owner and publisher of the Uvalde Leader-News newspaper, said people who were not directly affected by the attack "have found it pretty easy to move forward.”

Garnett also believes getting the trial out of Uvalde was a good move for the city.

“The community was terribly divided in the aftermath," he said. If the trial were held there, "you would have so many opportunities to inflame things.”

Some victims' parents sought political office but with little success.

Javier Cazares, Jackie’s father, ran unsuccessfully in 2022 for the Uvalde County Commission as a write-in candidate on a platform that called for more rigorous police training. Kimberly Mata-Rubio, whose daughter Lexi was killed, made a bid for mayor in her memory in 2023 but lost.

Rizo, who won a seat on the school board in 2024, agreed that many Uvalde residents have moved on from May 24, 2022. He finds that maddening.

“I hear, ‘They tried the best they could’ and 'Do you blame them? Would you have taken a bullet?’" Rizo said. “It angers me and frustrates me."

Uvalde has a strong tradition of supporting law enforcement. Two of the people killed came from law enforcement families.

Mata-Rubio’s husband was a sheriff’s deputy who went to the school after the attack started. The other teacher killed, Eva Mireles, was married to one of the first officers to enter the building.

The families have sought justice through multiple legal paths. Federal and state lawsuits have been filed against law enforcement, a gun manufacturer, a video game company and the Meta social media company over the shooting. Those cases are still pending.

The families reached a $2 million settlement with the city that promised higher standards and better training for police.

Relatives also lobbied state and federal lawmakers for stricter gun control laws that never advanced. But earlier this year, Texas lawmakers passed the Uvalde Strong Act, which sets new requirements for active shooter training and shooting response plans for police and schools.

Duran wants accountability not just for her sister but also for a beloved brother-in-law who died two days after the shooting.

Irma's husband, Joe, was watching a television report on the shooting when he heard that authorities missed their chance to end the attack quickly. He immediately fell to the floor with an apparent heart attack, Duran said.

The conviction of a single officer out of almost 400 would bring little in the way of justice, Duran said.

“The only justice is going to be when they take their final breath,” she said. “And then God will judge them.”

A framed photo of Robb Elementary teacher Irma Garcia is seen at the home of her sister, Velma Lisa Duran on Dec. 19, 2025, in San Antonio. (AP Photo/Kin Man Hui)

Velma Lisa Duran, sister of Robb Elementary teacher Irma Garcia, reflects on the 2022 Uvalde, Texas, school shooting during an interview on Dec. 19, 2025, in San Antonio. (AP Photo/Kin Man Hui)

Velma Lisa Duran, sister of Robb Elementary teacher Irma Garcia, keeps a plant at her home that was similar to the one that her sister kept in her classroom, Dec. 19, 2025, in San Antonio. (AP Photo/Kin Man Hui)

FILE - This booking image provided by the Uvalde County, Texas, Sheriff's Office shows Adrian Gonzales, a former police officer for schools in Uvalde, Texas. (Uvalde County Sheriff's Office via AP, File)

FILE - Flowers and candles are placed around crosses to honor the victims killed in a school shooting, May 28, 2022, outside Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong, File)