BEIRUT (AP) — Lebanon's moves to remove weapons from all non-state groups and assert full state control are as important as financial reforms if the economy is to recover after years of crisis, the economy minister said Thursday.

“You need economic reforms, but you also need security and political reforms,” Amer Bisat told The Associated Press after a cabinet session in which the Lebanese military reported progress on a plan to disarm Hezbollah and non-state groups and expand deployment in southern Lebanon.

“We’re moving, and we’re moving fairly decisively and clearly in that direction,” he said, adding that asserting full sovereignty to boost investor confidence goes beyond disarmament and military deployment in the south.

“(It) is also the control of the borders, control of the airport, control over smuggling, money-laundering, terrorist activities,” said Bisat.

Lebanon's military said Thursday it has completed the first phase of the plan, though Israel maintains that Hezbollah is still present and rearming in areas the army said it now fully controls.

Israel and Hezbollah’s monthslong war in 2024 battered large swaths of the country and set it back the further economically after years of crisis. The World Bank estimates $11 billion in damages and economic losses from the conflict. The country fell into a protracted financial crisis in 2019 after decades of corruption and mismanagement.

Bisat is a member of Prime Minister Nawaf Salam’s reformist government which was appointed last year with a mandate to reform the country’s banks and make the country’s crippled economy viable again.

For years, the government has stalled on making wide-reaching reforms that could implicate the country’s wide network of cronies. However, western countries and wealthy Gulf Arab monarchies that once poured large sums of money into the country, say that investment and substantial help won’t come without economic and security reforms.

Years of talks with the International Monetary Fund for a bailout have failed to produce a deal.

“We have a credibility gap, we need an international framework to help us solve our problems,” Bisat said. “The days in which people help us without us doing our homework are gone.”

Bisat is among a slim majority of cabinet ministers, alongside Salam, who last month endorsed a draft fiscal gap law to determine the extent of losses — estimated to be tens of billions of dollars — suffered by Lebanese banks during the country’s financial meltdown in 2019 and provide a mechanism to return depositors’ funds that were wiped out at the time. The draft law has been criticized from all sides and it is unclear whether it will be passed by the parliament.

“This is an extremely important piece of legislation, without which this economy just will not be able to take off,” said Bisat, who insisted that the law is not “Biblical” but a framework to start serious discussions. “This problem is extremely complicated financially. The size of the gap is very large.”

Bisat sees economic opportunities globally, especially with Gulf countries that are slowly rebuilding ties with Beirut after previously cutting them to push back against Hezbollah's influence in the country. He also cites regional changes, notably the downfall of the Assad dynasty in Syria, and wealthy Gulf states' appetite in boosting international investments as they diversify their economies, as further incentive for Lebanon to accelerate reforms.

But none of these opportunities will materialize without reforms to restructure the banks and tackle corruption.

“Waiting is not an option. Precisely because time is not our friend,” the minister said.

Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi, left, meets with Amer Bisat, the Lebanese minister of Economy and Trade, in Beirut, Lebanon, Tuesday, Jan. 8, 2026. (AP Photo/Hussein Malla)

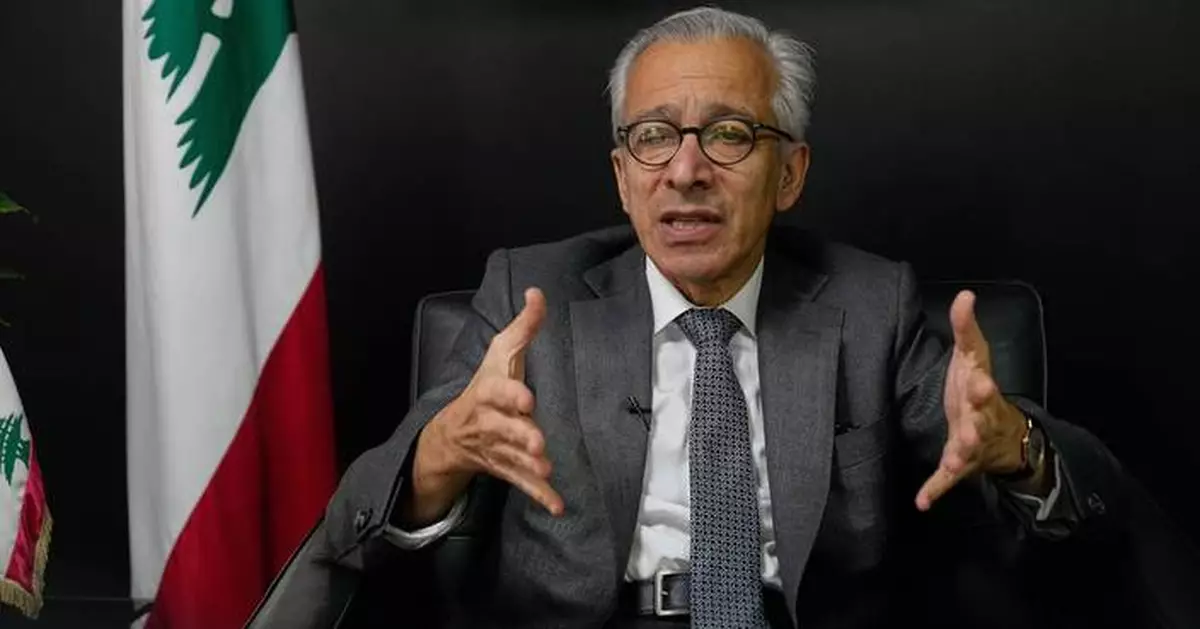

Amer Bisat, the Lebanese minister of Economy and Trade, speaks during an interview with Associated Press, in Beirut, Lebanon, Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026. (AP Photo/Hussein Malla)

A quarterback reportedly reneging on a lucrative deal to hit the transfer portal, only to return to his original school. Another starting QB, this one in the College Football Playoff, awaiting approval from the NCAA to play next season, an expensive NIL deal apparently hanging in the balance. A defensive star, sued by his former school after transferring, filing a lawsuit of his own.

It is easy to see why many observers say things are a mess in college football even amid a highly compelling postseason.

“It gets crazier and crazier. It really, really does,” said Sam Ehrlich, a Boise State legal studies professor who tracks litigation against the NCAA. He said he might have to add a new section for litigation against the NCAA stemming just from transfer portal issues.

“I think a guy signing a contract and then immediately deciding he wants to go to another school, that’s a kind of a new thing,” he said. “Not new kind of historically when you think about all the contract jumping that was going on in the ’60s and ’70s with the NBA. But it’s a new thing for college sports, that’s for sure.”

Washington quarterback Demond Williams Jr. said late Thursday he will return to school for the 2026 season rather than enter the transfer portal, avoiding a potentially messy dispute amid reports the Huskers were prepared to pursue legal options to enforce Williams’ name, image and likeness contract.

Edge rusher Damon Wilson is looking to transfer after one season at Missouri, having been sued for damages by Georgia over his decision to leave the Bulldogs. He has countersued.

Then there is Ole Miss quarterback Trinidad Chambliss, who reportedly has a new NIL deal signed but is awaiting an NCAA waiver allowing him to play another season as he and the Rebels played Thursday night's Collge Football Playoff semifinal against Miami. On the Hurricanes roster: Defensive back Xavier Lucas, whose transfer from Wisconsin led to a lawsuit against the Hurricanes last year with the Badgers claiming he was improperly lured by NIL money. Lucas has played all season for Miami. The case is pending.

Court rulings have favored athletes of late, winning them not just millions in compensation but the ability to play immediately after transferring rather than have to sit out a year as once was the case. They can also discuss specific NIL compensation with schools and boosters before enrolling and current court battles include players seeking to play longer without lower-college seasons counting against their eligibility and ability to land NIL money while doing it.

Ehrlich compared the situation to the labor upheaval professional leagues went through before finally settling on collective bargaining, which has been looked at as a potential solution by some in college sports over the past year. Athletes.org, a players association for college athletes, recently offered a 38-page proposal of what a labor deal could look like.

“I think NCAA is concerned, and rightfully so, that anything they try to do to tamp down this on their end is going to get shut down,” Ehrlich said. “Which is why really the only two solutions at this point are an act of Congress, which feels like an act of God at this point, or potentially collective bargaining, which has its own major, major challenges and roadblocks.”

The NCAA has been lobbying for years for limited antitrust protection to keep some kind of control over the new landscape — and to avoid more crippling lawsuits — but bills have gone nowhere in Congress.

Collective bargaining is complicated and universities have long balked at the idea that their athletes are employees in some way. Schools would become responsible for paying wages, benefits, and workers’ compensation. And while private institutions fall under the National Labor Relations Board, public universities must follow labor laws that vary from state to state; virtually every state in the South has “right to work” laws that present challenges for unions.

Ehrlich noted the short careers for college athletes and wondered whether a union for collective bargaining is even possible.

To sports attorney Mit Winter, employment contracts may be the simplest solution.

“This isn’t something that’s novel to college sports,” said Winter, a former college basketball player who is now a sports attorney with Kennyhertz Perry. “Employment contracts are a huge part of college sports, it’s just novel for the athletes.”

Employment contracts for players could be written like those for coaches, he suggested, which would offer buyouts and prevent players from using the portal as a revolving door.

“The contracts that schools are entering into with athletes now, they can be enforced, but they cannot keep an athlete out of school because they’re not signing employment contracts where the school is getting the right to have the athlete play football for their school or basketball or whatever sport it is,” Winter said. “They’re just acquiring the right to be able to use the athlete’s NIL rights in various ways. So, a NIL agreement is not going to stop an athlete from transferring or going to play whatever sport it is that he or she plays at another school.”

There are challenges here, too, of course: Should all college athletes be treated as employees or just those in revenue-producing sports? Can all injured athletes seek workers' compensation and insurance protection? Could states start taxing athlete NIL earnings?

Winter noted a pending federal case against the NCAA could allow for athletes to be treated as employees more than they currently are.

“What’s going on in college athletics now is trying to create this new novel system where the athletes are basically treated like employees, look like employees, but we don’t want to call them employees,” Winter said. “We want to call them something else and say they’re not being paid for athletic services. They’re being paid for use of their NIL. So, then it creates new legal issues that have to be hashed out and addressed, which results in a bumpy and chaotic system when you’re trying to kind of create it from scratch.”

He said employment contracts would allow for uniform rules, including how many schools an athlete can go to or if the athlete can go to another school when the deal is up. That could also lead to the need for collective bargaining.

“If the goal is to keep someone at a school for a certain defined period of time, it’s got to be employment contracts,” Winter said.

Get poll alerts and updates on the AP Top 25 throughout the season. Sign up here. AP college football: https://apnews.com/hub/ap-top-25-college-football-poll and https://apnews.com/hub/college-football

Mississippi quarterback Trinidad Chambliss (6) runs the ball during the second half of the Fiesta Bowl NCAA college football playoff semifinal game against Miami, Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026, in Glendale, Ariz. (AP Photo/Rick Scuteri)