CHICAGO (AP) — Alex Bregman was clear and concise. His biggest priorities are his family and winning baseball games.

Bregman's wife, Reagan, and sons, Knox and Bennett, watched from the front row on Thursday as he detailed his reasons for signing with the Chicago Cubs in free agency. He displayed his other priority on the back of his new pinstriped jersey.

“I wore No. 3 because I wanted a third championship,” Bregman said.

That obsession with winning, and all the ways it affects the players around him, was a major reason why the Cubs went out of their comfort zone to reel in the All-Star third baseman with a $175 million, five-year contract.

The deal includes a no-trade provision and $70 million in deferred payments. The Cubs have deferred money before — namely in contracts for outfielder Jason Heyward and pitcher Jon Lester that helped the team win the 2016 World Series — but nothing like the number they went to for Bregman.

That's how much they wanted him.

“When you do make a significant commitment to a player, you want to make sure that the person and the player are both at the highest level, and with Alex, we know that,” Cubs president of baseball operations Jed Hoyer said.

Hoyer has been following Bregman's career from afar for more than a decade, long before the infielder was selected by Houston with the No. 2 pick in the 2015 amateur draft — one spot behind current Cubs shortstop Dansby Swanson.

Bregman, who turns 32 in March, played his first nine seasons with the Astros, winning World Series titles in 2017 and 2022 — although the first of those was during a sign-stealing scandal that earned Bregman and his teammates plenty of scorn.

He also was pursued by Chicago before he signed a $120 million, three-year contract with Boston last February, a deal that included opt-outs after each of the first two seasons.

“You sort of heard stories about his level of confidence,” Hoyer said.

When Bregman returned to free agency after batting .273 with 18 homers and 62 RBIs in his only season with the Red Sox, the Cubs went after him again. Their consistent pursuit meant something to Bregman, and their previous conversations helped lay the groundwork for their new partnership.

“From the beginning of the offseason, the Cubs expressed to me that they wanted me to be here, and they were committed to that, committed to my family,” Bregman said. “Yeah, I cannot wait to get to work with all the guys on the team in that clubhouse and hopefully win a lot of baseball games and build something really special for a long time to come.”

He isn't wasting any time, either. Shortly after the deal was completed, Bregman asked for reports on his new teammates and a meeting with the organization's minor league staff. He wanted to make sure he was talking about the right things with other players.

He has connected with several of his new teammates already, including Swanson, pitcher Jameson Taillon and outfielders Ian Happ and Pete Crow-Armstrong. He'll have an opportunity to speak with more players at the team's annual fan convention this weekend.

“It's been fun,” Bregman said. “I feel like you can sense the excitement here not only from the Cubs fans, but also the players. They're very excited as well, and that's good.”

Bregman went to Hoyer’s office on Wednesday to make sure he was OK with him playing for the United States in the World Baseball Classic. Hoyer said he responded positively, and Bregman assured him he will visit Chicago’s spring training complex in the mornings to be around his new team.

“There's already been countless examples of things he's working on that no one's asked him to do,” Hoyer said. “I think that's how he thinks about his role. It's not just about getting his workouts in. It's about making sure he's integrated with the entire team.”

Bregman joins a Chicago team that won 92 games last season and reached the playoffs for the first time since 2020. The Cubs were eliminated by Milwaukee in a five-game Division Series.

Matt Shaw was the team's regular third baseman last year, with Swanson at shortstop, Nico Hoerner at second and Michael Busch at first. Shaw also can play second, but Hoyer sounded as if he planned to keep his group of infielders for insurance.

Bregman was limited to 114 games last year because of a quadriceps injury. The durable Swanson played in 159 games during the regular season, but he turns 32 in February. Hoerner had right flexor tendon surgery in October 2024.

The 24-year-old Shaw could move into a super-utility role to help keep everyone healthy and fresh, including spending time in the outfield.

“Matt Shaw's a really good athlete,” Hoyer said. “He hadn't played much third and was a Gold Glove finalist last year. I have no questions about his defense at any position or his ability to learn something really quickly.”

AP MLB: https://apnews.com/mlb

Catrina Connelly, left, her husband Patrick Connelly, their baby Declan with their dog Millie stand outside of Wrigley Field where the marquee displays new Chicago Cubs infielder Alex Bregman, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026. (AP Photo/Nam Y. Huh)

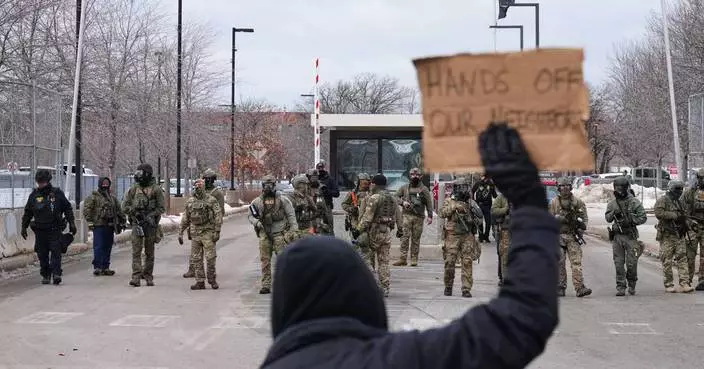

Federal immigration agents deployed to Minneapolis have used aggressive crowd-control tactics that have become a dominant concern in the aftermath of the deadly shooting of a woman in her car last week.

They have pointed rifles at demonstrators and deployed chemical irritants early in confrontations. They have broken vehicle windows and pulled occupants from cars. They have scuffled with protesters and shoved them to the ground.

The government says the actions are necessary to protect officers from violent attacks. The encounters in turn have riled up protesters even more, especially as videos of the incidents are shared widely on social media.

What is unfolding in Minneapolis reflects a broader shift in how the federal government is asserting its authority during protests, relying on immigration agents and investigators to perform crowd-management roles traditionally handled by local police who often have more training in public order tactics and de-escalating large crowds.

Experts warn the approach runs counter to de-escalation standards and risks turning volatile demonstrations into deadly encounters.

The confrontations come amid a major immigration enforcement surge ordered by the Trump administration in early December, which sent more than 2,000 officers from across the Department of Homeland Security into the Minneapolis-St. Paul area. Many of the officers involved are typically tasked with arrests, deportations and criminal investigations, not managing volatile public demonstrations.

Tensions escalated after the fatal shooting of Renee Good, a 37-year-old woman killed by an immigration agent last week, an incident federal officials have defended as self-defense after they say Good weaponized her vehicle.

The killing has intensified protests and scrutiny of the federal response.

On Monday, the American Civil Liberties Union of Minnesota asked a federal judge to intervene, filing a lawsuit on behalf of six residents seeking an emergency injunction to limit how federal agents operate during protests, including restrictions on the use of chemical agents, the pointing of firearms at non-threatening individuals and interference with lawful video recording.

“There’s so much about what’s happening now that is not a traditional approach to immigration apprehensions,” said former Immigration and Customs Enforcement Director Sarah Saldaña.

Saldaña, who left the post at the beginning of 2017 as President Donald Trump's first term began, said she can't speak to how the agency currently trains its officers. When she was director, she said officers received training on how to interact with people who might be observing an apprehension or filming officers, but agents rarely had to deal with crowds or protests.

“This is different. You would hope that the agency would be responsive given the evolution of what’s happening — brought on, mind you, by the aggressive approach that has been taken coming from the top,” she said.

Ian Adams, an assistant professor of criminal justice at the University of South Carolina, said the majority of crowd-management or protest training in policing happens at the local level — usually at larger police departments that have public order units.

“It’s highly unlikely that your typical ICE agent has a great deal of experience with public order tactics or control,” Adams said.

DHS Secretary Tricia McLaughlin said in a written statement that ICE officer candidates receive extensive training over eight weeks in courses that include conflict management and de-escalation. She said many of the candidates are military veterans and about 85% have previous law enforcement experience.

“All ICE candidates are subject to months of rigorous training and selection at the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center, where they are trained in everything from de-escalation tactics to firearms to driving training. Homeland Security Investigations candidates receive more than 100 days of specialized training," she said.

Ed Maguire, a criminology professor at Arizona State University, has written extensively about crowd-management and protest- related law enforcement training. He said while he hasn't seen the current training curriculum for ICE officers, he has reviewed recent training materials for federal officers and called it “horrifying.”

Maguire said what he's seeing in Minneapolis feels like a perfect storm for bad consequences.

“You can't even say this doesn't meet best practices. That's too high a bar. These don't seem to meet generally accepted practices,” he said.

“We’re seeing routinely substandard law enforcement practices that would just never be accepted at the local level,” he added. “Then there seems to be just an absence of standard accountability practices.”

Adams noted that police department practices have "evolved to understand that the sort of 1950s and 1960s instinct to meet every protest with force, has blowback effects that actually make the disorder worse.”

He said police departments now try to open communication with organizers, set boundaries and sometimes even show deference within reason. There's an understanding that inside of a crowd, using unnecessary force can have a domino effect that might cause escalation from protesters and from officers.

Despite training for officers responding to civil unrest dramatically shifting over the last four decades, there is no nationwide standard of best practices. For example, some departments bar officers from spraying pepper spray directly into the face of people exercising Constitutional speech. Others bar the use of tear gas or other chemical agents in residential neighborhoods.

Regardless of the specifics, experts recommend that departments have written policies they review regularly.

“Organizations and agencies aren’t always familiar with what their own policies are,” said Humberto Cardounel, senior director of training and technical assistance at the National Policing Institute.

“They go through it once in basic training then expect (officers) to know how to comport themselves two years later, five years later," he said. "We encourage them to understand and know their training, but also to simulate their training.”

Adams said part of the reason local officers are the best option for performing public order tasks is they have a compact with the community.

“I think at the heart of this is the challenge of calling what ICE is doing even policing,” he said.

"Police agencies have a relationship with their community that extends before and after any incidents. Officers know we will be here no matter what happens, and the community knows regardless of what happens today, these officers will be here tomorrow.”

Saldaña noted that both sides have increased their aggression.

“You cannot put yourself in front of an armed officer, you cannot put your hands on them certainly. That is impeding law enforcement actions,” she said.

“At this point, I’m getting concerned on both sides — the aggression from law enforcement and the increasingly aggressive behavior from protesters.”

Law enforcement officers at the scene of a reported shooting Wednesday, Jan. 14, 2026, in Minneapolis. (AP Photo/Adam Gray)

Federal immigration officers confront protesters outside Bishop Henry Whipple Federal Building, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026, in Minneapolis. (AP Photo/Adam Gray)

People cover tear gas deployed by federal immigration officers outside Bishop Henry Whipple Federal Building, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026, in Minneapolis. (AP Photo/Adam Gray)

A man is pushed to the ground as federal immigration officers confront protesters outside Bishop Henry Whipple Federal Building, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026, in Minneapolis. (AP Photo/John Locher)

A woman covers her face from tear gas as federal immigration officers confront protesters outside Bishop Henry Whipple Federal Building, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026, in Minneapolis. (AP Photo/Adam Gray)