LA QUINTA, Calif. (AP) — Blades Brown handled the scariest tee shot at PGA West to an island green like a seasoned pro Saturday in The American Express. And then he looked the part of an 18-year-old, finding a young fan along the ropes for a game of “paper, scissors, rocks” as he headed toward the green.

The teen is having a blast in the California desert, and it could get even better.

He goes into the final round one shot behind Si Woo Kim — another teen prodigy from a generation ago — and tied with none other than Scottie Scheffler, the No. 1 player in the world.

Pressure? It didn't look like it. Didn't sound like it, either.

“I’m 18 years old playing on the PGA Tour. How awesome is that?” Brown said. “I finished high school about two weeks ago, so it’s nice to have that burden off my back, but I’m really looking forward to tomorrow.”

Kim, who was 17 when he made it through the final version of the old Q-school in 2012, quietly went about his business at La Quinta Country Club with a 6-under 66 to grab a one-shot lead, a good day to be at one of the easier courses when the wind finally arrived in the Coachella Valley.

Kim was at 22-under 194.

Scheffler and Brown were on the tough Stadium Course at PGA West — even tougher with the fan turned on — and each shot a 68 with a finish that was vastly different.

Brown, playing an hour-and-a-half ahead, finished off his round with three straight birdies, the one from 25 feet on the island-green 17th and from 45 feet on the final hole.

“Hooped two putts coming in, and that was cool,” he said. (He also won the game with the kid on the fifth try — rock beats scissors).

Scheffler didn't have a lot of close birdie chances with a wedge in hand (the wind and firmest set of greens had a lot to do with that) but he hit two of his best shots with a drive that covered the bunker and a 5-iron into the dangerous green on the par-5 16th.

“Probably the best shot of the day,” he said.

That set up birdie, and then he escaped a tough lie in dormant grass by holing a 25-foot par putt.

For a sport that has 165 years of championship golf behind it, the records can be a little messy. Brown could become the youngest winner in nearly a century, probably longer.

Charles Kocsis won the Michigan Open in 1931 at 18 years, six months — a couple of months younger than Brown — but that tournament was regarded as a regional event. Young Tom Morris won his first British Open in 1868 at age 17.

Regardless, it would be phenomenal feat, and that's without the road here.

With all the attention on his age, Scheffler was more impressed with Brown playing his eighth round in as many days on Sunday. Brown played the Korn Ferry Tour event in the Bahamas (a tie for 17th) that ended Wednesday. He tapped in, showered, got use of a private jet to fly that night to California and arrived at his hotel about 14 hours before his tee time.

And then he competed against the strongest field in some three decades at The American Express.

“I don't think people understand how difficult that is to do,” Scheffler said. He doesn't know a lot about Brown except to say, “Obviously, he's got a lot of talent.”

Brown didn't look the least bit fatigued not at his age and this chance in front of him.

“I feel great,” Brown said. “I got another opportunity to see what we can make happen tomorrow. Got another 18 holes and, yeah, should be fun.”

The other two guys in the final group should have plenty of fun, too. Scheffler helped get Kim a membership at Royal Oaks in Dallas, and they are regulars on the weekend game. They competed plenty in the month leading to The American Express.

Scheffler confirmed Kim beat him the last time they played by adding, “Yes, I gave him back a little of his money.” Scottie always keeps score.

Kim finished at La Quinta and said he wanted mainly to have fun on Sunday, which was followed quickly by a query: “Am I playing with Scottie?”

“Hopefully playing with Scottie, and we can have some fun,” Kim said.

It was PGA West some 13 years ago that a 17-year-old Kim made it through the last edition of the old Q-school, having to wait until he was 18 to join the PGA Tour. He was 21 when he captured The Players Championship, one of his four tour victories. He has become a favorite of most players.

“Have you ever spent any time with him? He's hilarious,” Scheffler said.

Sunday might be all business, and they all know enough about this tournament not to get wrapped up in the final group. Scores have been low even in a difficult wind.

Former U.S. Open champion Wyndham Clark, who can go low without notice, and Eric Cole each shot 66 at La Quinta and were two shots behind. Another shot back was Tom Hoge, who had a 65 at La Quinta. Nine players in all were separated by four shots.

AP golf: https://apnews.com/hub/golf

Blades Brown misses a birdie putt at the second hole during the third round of the American Express golf event on the Pete Dye Stadium Course at PGA West Saturday, Jan. 24, 2026, in La Quinta, Calif. (AP Photo/Ross D. Franklin)

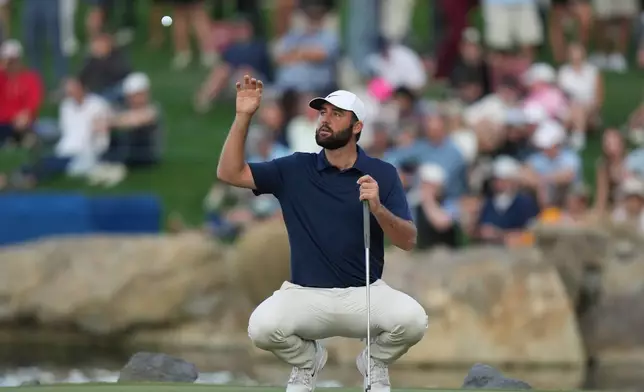

Scottie Scheffler reaches up to catch his golf ball his caddie tossed to him at the 18th green during the third round of the American Express golf event on the Pete Dye Stadium Course at PGA West Saturday, Jan. 24, 2026, in La Quinta, Calif. (AP Photo/Ross D. Franklin)

Blades Brown celebrates a birdie putt at the 18th green during the third round of the American Express golf event on the Pete Dye Stadium Course at PGA West Saturday, Jan. 24, 2026, in La Quinta, Calif. (AP Photo/Ross D. Franklin)

Si Woo Kim, of South Korea, hits his tee shot at the third hole during the second round of the American Express golf event at the Pete Dye Stadium Course at PGA West Friday, Jan. 23, 2026, in La Quinta, Calif. (AP Photo/Ross D. Franklin)

Scottie Scheffler pumps his fist after making a par on the 18th hole during the third round of the American Express golf event on the Pete Dye Stadium Course at PGA West Saturday, Jan. 24, 2026, in La Quinta, Calif. (AP Photo/Ross D. Franklin)